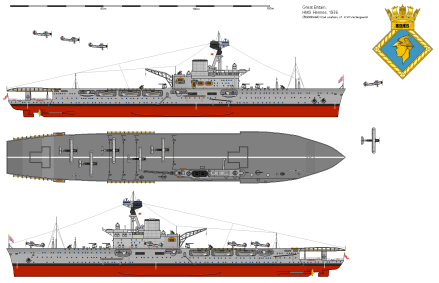

This is the 10,850 ton Aircraft Carrier HMS Hermes under fire, ablaze and sinking during World War 2. As Simonstown in South Africa was a British Naval base thousands of South Africans in WW2 served in the Royal Navy as well as in the South African Naval Forces (SANF). The loss of an aircraft carrier the size of the HMS Hermes is bound to include a South African honour roll and unfortunately this one does. Read on for their story.

HMS Hermes’ short history

The HMS Hermes was the first purpose-built aircraft carrier in the world. The design was based on that of a cruiser and the ship was intended for a similar scouting role. She was built by Armstrong Whitworth and launched 11 September 1919.

After a distinguished wartime career she was lost 9 April 1942. HMS Hermes had a small aircraft complement, light protection and anti-aircraft armament. She had a limited high-speed endurance and stability problems caused by the large starboard island, with fuel having to be carefully distributed to balance the ship.

HMS Hermes was deemed unsuitable for operations in European waters, and was consequently employed in trade protection in the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans until March 1942.

HMS Hermes in South Africa

In June 1941, the HMS Hermes took passage to South Africa, where she undertook repairs from July to October in HM Dockyard Simonstown. By November she was ready to re-rejoin the action as part of convoy defence in Indian Ocean. She took on a large contingent of South African Naval Forces personnel seconded to The Royal Navy’s requirements as part of her crew. The HMS Hermes then sailed from Cape Town accompanied by the Battleship HMS Prince of Wales on passage up the Indian Ocean.

In December 1941 she undergoes more refitting, again in South Africa, this time in Durban. By February 1942, she leaves Durban (with more South African personnel) and resumes convoy defence duties in the Indian Ocean.

By March she joins the Eastern Fleet searching for Japanese warships in Indian Ocean to engage.

Japanese attack on Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

With Japan’s entry into the war, and especially after the fall of Singapore, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) became a front-line British base. The Royal Navy’s East Indies Station and Eastern Fleet was moved to Colombo and Trincomalee.

HMS Hermes on patrol with HMS Dorsetshire – 1942

Admiral Sir James Somerville was appointed as the commander of the British Eastern Fleet, and he decided to withdraw main component the fleet to Addu Atoll in the Maldives, leaving a small force to defend Ceylon (Sri Lanka) consisting of an aircraft carrier, the HMS Hermes, two heavy cruisers – the HMS Cornwall and HMS Dorsetshire, one Australian Destroyer the HMSAS Vampire and the flower class corvette HMS Hollyhock.

The Royal Navy’s own ‘Pearl Harbour’

The Imperial Japanese Navy, in much the same way and with the same objectives that were used at Pearl Harbour against the American fleet planned a decisive attack of the British Eastern Fleet to end their presence in the North Indian and Pacific oceans. Unaware that the main body of the British fleet had moved to the Maldives, they focused their plan on Colombo.

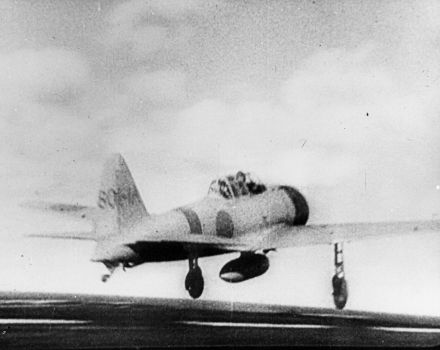

The planned Japanese attack was to become collectively known as the Easter Sunday Raid and the Japanese fleet comprised five aircraft carriers plus supporting ships under the command of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo.

In an almost exact copy of the raid on the American fleet at Peal Harbour (as if no learnings were made by the Allies), on 4 April 1942, the Japanese fleet was located by a Canadian PBY Calatina aircraft, the Catalina radioed the position of the Japanese Fleet to The British Eastern Fleet which alerted the British to the impending attack before it was shot down by six Japanese Zero fighters from the carrier Hiryu, However, despite the warning Nagumo’s air strike on Colombo the next day, Easter Sunday 5th April achieved near-complete surprise (Pearl Harbour was also attacked on a weekend). The British Radar installations were not operating, they were shut down for routine maintenance.

Japanese Carrier Hiryu

The first attack wave of Japanese planes took off in pre-dawn darkness (30 minutes before sunrise) from the aircraft carriers Akagi, Hiryu and Soryu, moving about 200 miles south of Sri Lanka. The first attack wave of 36 fighters, 54 dive bombers, and 90 level bombers was led by Captain Mitsuo Fuchida the same officer who led the air attack on Pearl Harbour.

The Heavy Cruisers, HMS Cornwall and HMS Dorsetshire set out in pursuit of the Japanese. On 5 April 1942, the two cruisers were sighted by a spotter plane from the Japanese cruiser Tone about 200 miles (370 km) southwest of Ceylon. A wave of Japanese dive bombers led by Lieutenant Commander Egusa took off from Japanese carriers to attack Cornwall and Dorsetshire, 320 km (170 nmi; 200 mi) southwest of Ceylon, and sank the two ships.

On 9 April, the Japanese focussed their attack on the harbour at Trincomalee and the British ships off Batticaloa. The HMS Hermes left the Royal Naval Base of Trincomalee, Ceylon escorted by the Australian Destroyer HMAS Vampire and HMS Hollyhock looking to engage the Imperial Japanese fleet which had attacked Colombo.

While sailing south off Batticaloa on the East Coast of Ceylon, this British flotilla was also attacked by the Japanese Carrier-Borne dive-bombers from the Imperial Japanese Task Force now in the process of attacking the Naval Base at Trincomalee.

Admiral Nagumo’s fleet unleashed the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters and bombers on the attack on Colombo on 5 April 1942.

Approximately 70 Japanese aircraft were despatched to bomb the HMS Hermes which sank within ten minutes of being hit by numerous aircraft bombs. HMAS Vampire was also sunk by bombs a short while later.

The HMS Hollyhock was about 7 nautical miles from the HMS Hermes escorting a tanker, the RFA Athelstane when the Hermes came under attack. The Hollyhock came under attack by the same Japanese aircraft and it too was bombed and sunk. For an in-depth appraisal on the South Africans lost on the Hollyhock follow this Observation Post link: “She immediately blew up”; Recounting South African sacrifice on the HMS Hollyhock

“Dante’s Inferno”

An eyewitness account of the sinking by Stan Curtiss says everything about the trauma and personal drama experienced by the sailors and officers:

“The AA guns crews did a magnificent job and to assist them because the planes at the end of their dive flew along the flight deck to drop their bombs and because the guns could not be fired at that low angle, all the 5.5.`s, mine included had orders to elevate to the maximum so that as the ship slewed from side to side to fire at will hoping that the shrapnel from the shells would cause some damage to the never ending stream of bombers that were hurtling down out of the sun to tear the guts out of my ship that had been my home for the past 3 years.

Suddenly there was an almighty explosion that seemed to lift us out of the water, the after magazine had gone up, then another, this time above us on the starboard side, from that moment onwards we had no further communication with the bridge which had received a direct hit, as a result of that our Captain and all bridge personnel were killed.

Suddenly there was an almighty explosion that seemed to lift us out of the water, the after magazine had gone up, then another, this time above us on the starboard side, from that moment onwards we had no further communication with the bridge which had received a direct hit, as a result of that our Captain and all bridge personnel were killed.

Only about fifteen minutes had passed since the start of the action and the ship was already listing to port, fires were raging in the hanger, she was on fire from stem to stern, just aft of my gun position was the galley, that received a direct hit also, minutes later we had a near miss alongside our gun, talk about a tidal wave coming aboard, our crew were flung yards, tossed like corks on a pond. Picking myself up and finding no bones broken, I called out to each number of our crew and got an answer from all of them (no-one washed overboard), we were lucky; our gun was the only one that did not get hit.

At this stage Hermes had a very heavy list to port and it was obvious that she was about to sink. As the sea was now only feet below our gun deck I gave the order “over the side lads, every man for himself, good luck to you all”.

Abandon ship had previously been given by word of mouth, the lads went over the side and I followed, hitting the water at 11.00 hours, this is the time my wristwatch stopped (I didn’t have a waterproof one).

As she was sinking the Japs were still dropping bombs on her and machine gunning the lads in the water. In the water I swam away from the ship as fast as I could, the ship still had way on and I wanted to get clear of the screws and also because bombs were still exploding close to the ship, the force of the explosions would rupture your stomach, quite a few of the lads were lost in this way after surviving Dante’s Inferno aboard, so it was head down and away”.

The aftermath

In all, 19 officers and 283 ratings (including 1 South African Officer and 17 South African Ratings) were Reported Missing in Action when HMS Hermes went down. 9 Ratings on HMAS Vampire were lost. 53 of the ship’s company of HMS Hollyhock were lost, of which 5 were members of the South African Naval Forces.

The hospital ship Vita rescued approximately 600 survivors and transferred them back to Colombo and later to Kandy for recuperation.

The air attack on the Royal Naval Base at Trincomalee killed 85 civilians in addition to the military losses while 36 Japanese aircraft were shot down during the attack.

The wreck of the HMS Hermes was re-discovered in 2006 approximately five nautical miles from shore, lying at a depth of fifty-seven meters. Divers attached the White Ensign to the rusting hull.

South African casualties aboard HMS Hermes

South African casualties aboard HMS Hermes

BRIGGS, Anthony Herbert Lindsay Sub-Lieutenant (Engineer) Royal Navy (South African national), MPK

BRYSON, Neil W, Ordinary Telegraphist, 69147 (SANF), MPK

BURNIE, Ian A, Able Seaman, 67786 (SANF), MPK

CLAYTON, Frederick H, Act/Engine Room Artificer 4c, 68102 (SANF), MPK

DE CASTRO, Alfred T, Stoker 1c, 67914 (SANF), MPK

KEENEY, Frederick W, Able Seaman, 67748 (SANF), MPK

KEYTEL, Roy, Able Seaman, 67296 (SANF), MPK

KIMBLE, Dennis C, Act/Engine Room Artificer 4c, 67600 (SANF), MPK

KRAUSE, Frederick E, Able Seaman, 68321 (SANF), MPK

RAPHAEL, Philip R, Able Seaman, 67841 (SANF), MPK

RICHARDSON, Ronald P, Able Seaman, 67494 (SANF), MPK

RILEY. Harry Air Mechanic 2nd Class, Fleet Air Arm, Royal Navy (South African national), MPK

TOMS, Ivanhoe S, Able Seaman, 67709 (SANF), MPK

VICKERS, Colin P, Able Seaman, 68296 (SANF), MPK

VORSTER, Jack P, Able Seaman, 67755 (SANF), MPK

WHITE, Edward G, Stoker, 68026 (SANF), MPK

WIBLIN, Eric R, Able Seaman, 67717 (SANF), MPK

YATES, Philip R, Supply Assistant, 67570 (SANF), MPK

Their names have not been forgotten.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens. Reference thanks to Graham Du Toit, other references and extracts taken from Wikipedia, Service Histories of Royal Navy Ships in World War 2 by Cdr Geoffrey B Mason RN (Retired). Image copyright Imperial War Museum and the Australian War Memorial.

Pingback: “She immediately blew up”; Recounting South African sacrifice on the HMS Hollyhock | The Observation Post

My grandfather was the HMS Hermes when it was sunk and I have a copy of a letter he wrote to my grandmother about it.

LikeLike

My father was one of the survivors of the HMS Hermes

LikeLike

Pingback: “A terrific explosion lifted the ship out of the water”; Recounting South African sacrifice on the HMS Cornwall | The Observation Post

Pingback: “They machine gunned us in the water”; Recounting South African Sacrifice on the HMS Dorsetshire | The Observation Post

Pingback: The South African Navy’s ‘darkest hour’ is not recognised and not commemorated | The Observation Post

Thank you. I found this absolutely fascinating.My father was a gunnery officer on the ship. He survived, but I now know only too late, how much this affected him later in life.

He spoke so little of the war and never really told our family anything when we asked.

For the rest of his life he had a strong dislike for the Japanese. Not that they sunk the ship… but that they machined gunned them in the water. He was wounded. And to this day the RN have never advised my mother, nor his parents, that he had survived.

This work of yours is to be highly recommended. Again thanks .

LikeLike

Pingback: South African sacrifice in the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm | The Observation Post

Pingback: The South African Navy’s ‘elephant in the room’ | The Observation Post

My father had been on HMS Hermes when she sailed from Freetown in Sierra Leone to Simon’s Town and had a collision with another ship en route. When she limped into Simon’s Town naval base for repairs, my father was more dead than alive as he not only had malaria, but also hepatitis. After the necessary repairs were made on the Hermes, she set sail for Ceylon, but as my father was still too ill for sea duties, he remained in Simon’s Town for a lengthy convalescence, during which the news came that the Hermes had been sunk off Ceylon with heavy loss of life. He always said that this was for him the narrowest escape from death during WW2.

LikeLike

My father, David de Villiers Clarke served on the Hermes. He and a group of friends joined the Royal Navy having travelled from Rhodesia to Simonstown from their school at Plumtree in Bulawayo. He was on board when Hermes was sunk by the Japanese. He and a group of fellow sailors were too far from the Vita to be rescued and they had no choice but to swim ashore (Ceylon) taking many hours to do so. Once on shore the survivors were taken by train to Colombo. He spoke briefly about his war time experiences. He also served on Formidable and on MTB boats built at the Thyssen factory in Knysna and used off the coast of Burma. Then I believe he served on two Russian Convoys. But sadly I should have asked more questions of those remarkable days and those remarkable men. Too late now sadly, MTDSRIP.

LikeLike