Huh! There was also a ‘white’ ‘armed insurgency movement against Apartheid! The ‘whites’ had their own ‘struggle’ insurgents, their own version of ‘umkhonto we sizwe’ (MK), the ‘whites’ had their very own anti-apartheid ‘terrorists’. What!

No way! This would be the universal chant of many South Africans – both black and white. This is not part of the current ANC inspired narrative on Apartheid in South Africa, we haven’t been taught this, the whites are the ‘guilty’ ones – not ‘liberators’ of Apartheid – what’s all this about?

Well, what if we told you that Apartheid did not just separate white and black people – it separated EVERYONE, including the whites. Grand Apartheid when it was conceived by the Nationalists had at its centre ideology the separation of ‘English’ white South Africans and ‘Afrikaans’ white South Africans. Afrikaner whites were to grow up separately, their own primary schools, their own youth movements (the Voortrekkers), their own church groups, their own High Schools, their own Universities and Colleges, their own exclusive youth sports leagues for everything – rugby, cricket, tennis you name it. The intention was that Afrikaner culture was to be guarded from not only ‘Black’ influence, it was to be guarded from the ‘English’ influence too.

This guarding stemmed from the Boer War. The scorched earth and concentration camp policies initiated by Kitchener had devastated the Afrikaner culture, family histories and culture lost forever, now the Nationalists had to rebuild it and the hard-liner Afrikaner Nationalists wanted nothing to do the British and their British descendants in South Africa. To them these were the English white South Africans concentrated mainly in Natal, the Western Cape and Johannesburg, Apartheid was also planned to separate Afrikaners from these most hated English – Black separation was part of the greater scheme, but so too white racial separation along cultural and even economic lines.

This guarding stemmed from the Boer War. The scorched earth and concentration camp policies initiated by Kitchener had devastated the Afrikaner culture, family histories and culture lost forever, now the Nationalists had to rebuild it and the hard-liner Afrikaner Nationalists wanted nothing to do the British and their British descendants in South Africa. To them these were the English white South Africans concentrated mainly in Natal, the Western Cape and Johannesburg, Apartheid was also planned to separate Afrikaners from these most hated English – Black separation was part of the greater scheme, but so too white racial separation along cultural and even economic lines.

So not surprisingly the White community was split down the middle over the Nationalists plans as to Apartheid when they came to power in 1948 surprisingly beating Smuts in a constitutional victory based on ‘seats’ and not a ‘majority’ based on ‘votes’ – that it was a shock win would be an understatement.

To many the plans of Apartheid were absurd and spelt doom for the Union, they heeded Smuts’ warnings, and in fact as a nominal vote count went Smuts ‘won’ the election by a good majority, signalling that the majority of Whites in South Africa did not favour the Apartheid tenets put forward by the National Party at all. Most of this was the English white voting bloc, but statistically it also made up of a significant bloc of White Afrikaners as well, These were Afrikaners who followed Smuts’ ideals and visions of unification, internationalism and democracy. Unfortunately, as seats went – the majority lost, and the Nationalists assumed power on a narrow margin.

The first mass anti-apartheid mobilisation

This leads to the first inconvenient fact – it was this voting White majority of Smuts supporters, which was the first community to mass mobilise protests against Apartheid in any significant way (not the Black community and the African National Congress ANC) – and it was all in response to the gerrymandering which brought the Nationalists into power in 1948 and their policy of Apartheid which was unpalatable to the broader White community.

This mass movement of whites mobilised against Apartheid primarily came from moderate, democratic and liberal white political parties (mainly Smuts’ United Party), as well as predominantly White driven equal rights movements, like The Black Sash feminist movement. But it materialised in real strength in a returning war veteran’s movement called ‘The Torch Commando’ led by an Afrikaner war hero – Adolph ‘Sailor’ Malan – started in 1951, the ‘Torch’ saw nearly a quarter of this anti-nationalist White voting base – 250,000 Whites – actively mark their protest to the national party and their ideology of Apartheid and join their protest movement.

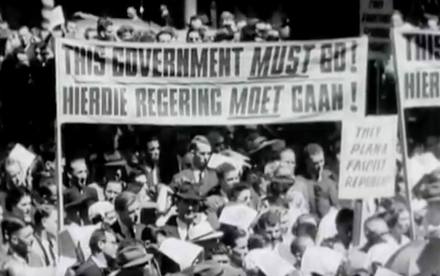

Torch Commando meeting – 1952

Read that again – 250,000 or a quarter of a million whites – signing up to an action group in active protest against Apartheid. This mass mobilisation of mainly whites in’ Torch’ protest rallies occurred nationwide in 1951 and not at the onset of the ANC’s Defiance Campaign on the 6th of April 1952. So as inconvenient truths go the first mass protest against Apartheid was led by the Torch and not by the ANC.

Now you don’t learn about that in South African historical narrative – then or now, and you have to ask yourself why – because there is more – much more?

The ‘white’ Anti-Apartheid Military ‘Threat’ from 1948 – 1959

To put this ‘White’ threat in perspective, the ANC, although representative of a bigger majority of people, had not yet mobilised itself in any significant way when the Nationalists came to power in 1948.

Prior to 1948 in the Union of South Africa, South African Black protest had come from a 1912 Anti-Pass Women’s protest which was very localised to Bloemfontein and a petition of 5000 signatures. It was not a national mass mobilisation of Black women against suffrage and pass laws in South Africa as the ANC like to position it and bend history now.

The next significant protest pre-1948 from the black community came in form of The 1946 miners strike, this was a one week mass strike action which ended in violence with government forces, the underpinning problem was a wage dispute, it was settled with a 10 shilling per day minimum wage (an increase from 2 shillings), and improved working conditions as the basis of the strikers demands. This action needs to be viewed as dispute on wages and conditions of miners with the mine companies primarily. It was also not really a national political protest and mobilisation against an entire system of Smuts’ government – which is again the way it is now very incorrectly presented to South Africans by the ANC.

From the Indian community there was Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha ‘peace’ campaign against Indian pass laws which eventually succeeded in 1914. Ironically Smuts’ and Gandhi actually became friends over the process and admired each other greatly till the day they both died.

The above posed nothing in any significant way as a military threat to the National Party in 1948, whilst weary of the ANC and what the Nationalists called ‘Swart Gevaar’ (Black Danger) they were not yet threatening, had not militarised itself and had not yet mass mobilised in any significant way. The ‘Torch Commando’, now that was threat to the Nationalists in 1950 – a very big and imminent threat.

Torch Commando rally in Caps Town. Protestors carrying thousands of oil soaked ‘torches’ of Liberty in defiance of Apartheid

Why? Because The Torch Commando was made up of second world war veterans, the national party had sat out the war in protest and in support of Nazi Germany and its ideology (which manifested itself in neo-Nazi Afrikaner nationalist movements like the Ossewabrandwag during the war itself). Now they were faced with 200,000 very angry, very well-trained ‘white’ soldiers who had been at war against Nazism for five long years – in effect thousands and thousands of combatants who had seen and survived the biggest war in this history of man, and they cared less for Nazism and fascism – nor could a great many of them really care for their Afrikaner Nationalist cabal.

The Torch Commando had within its ranks White members from various political groups, trade unions, political parties and veterans associations. In the main it was made up of members who had supported Smuts call to arms in WW2 – moderate members from the United Party who feared the disintegration of democracy and broader society under Apartheid – standing alongside broad military veteran associations like The South African Legion and the Memorable Order of Tin Hats.

The Torch Commando also had within it’s a ranks a smaller, but far more militant and vocal grouping. This grouping was made up of members of a veterans association called The Springbok Legion, alongside members of South Africa’s Liberal Party and members of The South African Communist Party (SACP). This part of the Torch Commando had firebrand future leaders in it – like Joe Slovo, Lionel Bernstein, Wolfie Kodesh, Jock Isacowitz, Jack Hodgson and Fred Carneso (all ‘communist’ members of The Springbok Legion), as well as Peter Kaya Selepe, a WW2 veteran and organiser of the African National Congress (ANC) in Orlando and Harry Heinz Schwarz, also a WW2 veteran who became the future Progressive and Democratic Party stalwart.

Torch Commando Rally

The Torch Commando at its zenith had 250,000 members, and in landmark protests across South Africa it brought of tens of thousands of protestors carrying ‘torches’ of light and freedom into physical defiance of the Nationalist government, the Torch Rally in Cape Town attracted 50,000 people and the one in Johannesburg put 75.000 mainly white protestors onto the streets. Now, that is a mass mobilisation movement.

A key objective underpinning the Torch was to remove the National Party from power by calling for an early election, the 1948 ‘win’ by The National Party was not a ‘majority win’, but a constitutional one, and the Torch wanted a groundswell to swing the military service vote (regarded as 200,000 in a voting population of a 1,000,000). A bunch of ex-WW2 military veterans trying to influence nearly a quarter of the voting bloc is a very big deal and a very big threat to the National Party.

The Torch at its core was absolutely against The National Party’s Apartheid ideology and viewed their government as unconstitutional when they started implementing policy – It regarded itself as a ‘pro-democracy’ movement and regarded the National Party’s policies as ‘anti-democratic’. The first action of the National Party to implement the edicts of Apartheid, was the Separate Representation of Voters Bill in 1951, which sought to disenfranchise the ‘coloured’ voters from the general voters roll, and it was in opposition to this legislation that the Torch Commando kicked off its campaign against the government. Its campaigns becoming progressively very vocal, and very large and they even started to clash with police in isolated cases.

The Nationalists, increasingly fearful of The Torch Commando splitting the White vote further and the fact that they had militant leanings acted in a manner that was to become their trade-mark, ‘decisively’ and moved to crush the Torch Commando. They did this by threatening Torch members, many of whom were still in the military or in civil service with their jobs if they continued membership and they moved to ban the Torch Commando through legislation.

Suppression of Communism Act

The legislative tool they used to crush the Torch Commando was the Suppression of Communism Act 44 which the Nationalists passed into law in July 1950. The act was a sweeping act and not really targeted to Communists per se, it was intended for anyone in opposition to Apartheid regardless of political affiliation.

The Act proscribed any party or group subscribing to Communism according to a uniquely broad definition of the term. The Act defined communism as any scheme aimed at achieving change–whether economic, social, political, or industrial–“by the promotion of disturbance or disorder” or any act encouraging “feelings of hostility between the European and the non-European races…calculated to further (disorder)”.

The government could deem any person to be a communist if it found that person’s aims to be aligned with these aims. After a nominal two-week appeal period, the person’s status as a communist became an un-reviewable matter of fact, and subjected the person to being barred from public participation, restricted in movement, or even imprisoned.

Passage of the Act was facilitated by the involvement of communists in any anti-apartheid movement, starting with The Torch Commando and eventually included any movement, individual or political party that advocated black equal rights and was deemed a ‘threat’.

Any ‘liberal’ movement came under the Suppression of Communism Act, not just the ANC and PAC, but also White members in the Liberal Party and the Black Sash, eventually it would even be applied to academics, novelists, journalists, poets, party leaders – anyone from the White community not buying into Apartheid in effect, and the penalty was harsh in the extreme. Imprisoned, deported or banned – labelled as ‘Traitors’ and ‘Communists’ – their voices were silenced.

-

Joe Slovo (right of picture) in WW2

Faced with a diversifying internal political agenda, anti-liberalism legislation and direct government pressure and sandbagging the Torch Commando split and collapsed, the moderate war veterans chose to continue their opposition through peaceful political opposition using the narrow but available means to them. The firebrand military radicals in the Torch Commando (like Joe Slovo) were a different matter entirely, and they moved to other political organisations, mainly the ANC and the Liberal Party, to give them their military advise and expertise, and embark on a more robust and subversive resistance to Apartheid.

Liberalism in ‘white’ South Africa

A key organisation in opposition to Apartheid in the 1950’s and 1960’s was the South African Liberal Party (SALP). Central to the Liberal Party were three men, Leslie Rubin Peter Brown and Alan Paton.

A key organisation in opposition to Apartheid in the 1950’s and 1960’s was the South African Liberal Party (SALP). Central to the Liberal Party were three men, Leslie Rubin Peter Brown and Alan Paton.

Leslie Rubin was an outspoken opponent of the apartheid regime in South Africa. He joined the South African army as a private in 1940, and was commissioned as an officer in the intelligence corps in north Africa during the war, and later attached to the Royal Air Force in Italy. After the war, he settled in Cape Town and joined the Torch Commando movement led by Sailor Malan.

With Alan Paton, Rubin created the Liberal party of South Africa (LPSA) within the definition of political parties that could stand for election and appoint ministers to Parliament. It founded on 9 May 1953 out of a belief that Jan Smuts’ United Party was in disarray after his death in 1950 and unable to achieve any real liberal progress in South Africa, the LPSA initially called for a franchise based vote for Black South Africans and later this evolved to a call for ‘one man one vote’.

Sailor Malan greets supporters at a Torch Commando Rally in Cape Town

The Liberal Party also attempted to draft Sailor Malan as a candidate, in addition to his role in the Torch Commando as the National President, however Sailor’s position on voting equality differed from Rubins’, Sailor conceded that a black majority would eventually govern South Africa, and he was very happy in that prediction, however Sailor sought economic empowerment of Black South Africans to address poverty as a priority (in this respect Sailor is years ahead of his time as it is exactly this issue – economic emancipation over political emancipation – only now has this become a burning priority for the EFF and ANC).

The Liberal Party elected to draft its members from The Torch Commando and Rubin became the first Chairman of the party in the Cape, in 1954 he was elected to the senate as what was then called a “natives’ representative”, a position he used to fight every piece of apartheid legislation. Whenever he got up to speak, the Minister of Native Affairs, the ‘architect’ of Apartheid – Dr Hendrik Verwoerd – would leave the chamber in protest. On one occasion, the entire Nationalist party caucus walked out.

The Liberal Party held the objective of bringing together committed Whites, Africans, Indians and Cape Coloured people in opposition to the Apartheid system. Rubin resigned from the senate in 1960, before the native representatives’ seats were abolished.

Like Rubin, Alan Paton volunteered for service during World War 2 but was refused, after the war be wrote Cry the Beloved Country to critical acclaim. He eventually became the President of The South African Liberal Party (SALP). Although he Paton did not have military experience it did not stop him from also initially joining the Torch Commando and publicly supporting Sailor Malan and his cause.

The SALP had close friendships with senior ANC and Indian Congress members. They often acted as a liaison between banned organisations and fully bought into the ideals espoused in the Freedom Charter. One of the party’s main focus areas was the fight against “black spot removals” where the Apartheid government uprooted black communities in order to shift them to new areas to create homogenous race blocks across the country. Peter Brown in particular fought tireless against these removals by helping communities organise, protest and receive access to legal advice.

Persecution by the State of the LPSA

The government responded to the LPSA and its policies by persecuting its members as it viewed the party’s policies as a threat to its apartheid policy. This was because the party had both black and white members in its ranks. Several members of the party were banned, disallowed to hold gatherings and harassed by the security police. In 1962, BJ Vorster accused the party of being nothing more than a “communist tool”.

Between March 1961 and April 1966, forty-one leading members of the LPSA were banned under the Suppression of Communism Act. This was despite the fact that they were not members of the Communist Party or supported communism.

On 13 May 1965, the Rand Daily Mail reported that leaflets were secretly scattered warning African members of the LPSA that they would be banned unless they desisted from participating in political activities of the LPSA.

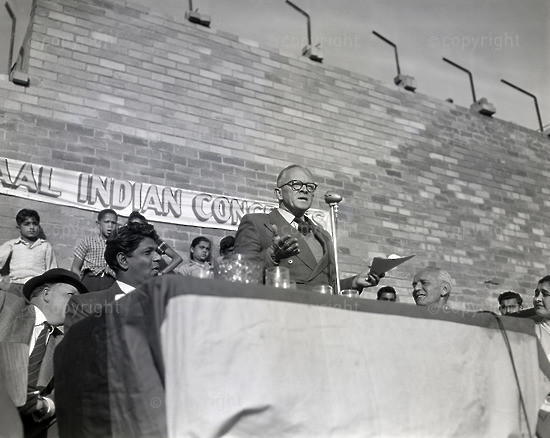

Alan Paton, President of SALP addresses a crowd in Fordsburg about the harm done to South Africa By the Group Areas Act

The state would harass and intimidate LPSA members. Security branch officers would attend party branch meetings and produce a warrant authorizing them to do so. The police would visit families of party members and ask them to persuade their relatives to leave the party, even Alan Paton was followed by the security branch, his telephone lines were tapped and his house was searched a number of times.

Due to political persecution, some members of the LPSA fled into to exile and became involved in anti-apartheid activities abroad. For example, Randolph Vigne was banned in 1963 and his house in Cape Town was fire bombed in an attempt to intimidate him. He left the country and went into exile in London where he worked closely with the Anti-Apartheid Movement there – so too Leslie Rubin who also went into exile in London.

Sharpeville and a ‘white lunatic’ liberal assassin

One of the defining moments in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa was the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960 and its aftermath.

On the Liberal Party front resistance by White liberals were about to a nasty turn, when in April 1960 – 19 days after the Sharpesville Massacre, Prime Minister H.F. Verwoerd, the architect of apartheid was giving his ‘good neighbourliness” speech at the Rand Show in Johannesburg.

After Verwoerd gave his opening speech, he returned to his seat in the grandstand where he was shot at point-blank range by David Pratt, who was an outspoken Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA) member and a wealthy English farmer from the Magaliesberg region outside of Pretoria. He joined the Liberal Party in 1953 and believed that a coalition between liberals and ‘verligte’ (enlightened) Afrikaners was the only solution to defeating the National Party at the polls.

Verwoerd miraculously survived the shooting, Pratt was arrested and claimed that he shot Verwoerd because he represented “the epitome of Apartheid” and it was necessary to shoot “the stinking monster of apartheid that was gripping South Africa and preventing South Africa from taking her rightful place among men”.

Pratt was also an epileptic with a long medical history of heavy epileptic fits. So to dismiss Pratt as a ‘lunatic’ – as to the Nationalists no white person in their right mind would shoot a white Prime Minister – so he was judged as ‘insane’. Pratt was sent to an institution for the mentally ill and by October 1961 he was found – rather too conveniently for the Nationalist government – hanging from a rolled-up bed-sheet.

The ‘white’ Anti-Apartheid Military ‘Threat’ from 1960 to 1963

The heavy-handed response of the state to the Sharpeville massacre with a state of emergency and the attempted assignation of Verwoerd in first half of 1960 saw thousands of activists detained and imprisoned.

Political movements such as the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) were banned and forced underground, and although the Liberal Party was not banned by the government, its members were not spared the wrath of the state. The crackdown forced the ANC and PAC to re-evaluate their approach to the liberation struggle and consider whether to abandon the principle of non-violence in favour of a campaign of military sabotage.

Sharpeville mass funeral – 1960

Mkhonto we Sizwe (MK) was co-founded by Nelson Mandela the wake of the Sharpville Massacre its founding represented the conviction in the face of the massacre that the ANC could no longer limit itself to nonviolent protest. In forming MK previous ‘white’ Torch Commando members, military veterans all, proved to be the critical and primary source of military expertise for training and command of MK – ex-Torch Commando members like Joe Slovo, Lionel Bernstein, Wolfie Kodesh, Cecil Williams, Fred Carneson, Brian Bunting and Jack Hodgson all became founding MK cadres in 1966.

Many of these ‘Springbok Legion’ and ‘Torch Commando’ members to join the MK were war veterans from South Africa’s Jewish community. They were particularly militant because of the treatment and ‘extermination’ of Jews by the Nazi Party during the second world war and saw the National Party and its political disposition to Jewish people as an equal threat (ironically this origin history of MK and its ‘jewish soldiers’ is conveniently forgotten by the ANC today when it comes to their overt criticism of Israel).

The Liberal Party of South Africa (SALP) was in the same boat as the ANC, also stuffed full of military veterans from the old Torch Commando and they too re-evaluated their approach to the ‘struggle’.

Despite the Liberal Party’s initial non-violent stance, the party was not spared the suppression of political activity after the declaration of the state of emergency in March 1960. The government launched a vicious attack on the Liberal Party, arresting 35 of its leading members and detaining them at the Fort in Johannesburg

The National Committee of Liberation (NCL)

In 1961, the detention and banning of leading Liberal Party members forced them to form their own resistance movement and cells, out of this came The National Committee of Liberation (NCL) and a declaration for armed resistance.

During their detention, Liberals – Monty Berman, Myrtle Berman, John Lang, Ernest Wentzel and others challenged the idea of peaceful protest when the government was evidently intent on using violence to suppress dissent. Monty Berman, Lang and Wentzel played an important role in the formation of the NCL. While in detention, they debated the need for an umbrella organisation for movements ready to carry out sabotage campaigns. The name National Liberation Committee, which the trio felt was all-encompassing, was chosen to refer to the umbrella body. After their release in August 1960, Myrtle Berman and Lang tried to engage with the ANC to form the NCL, but were unsuccessful.

The NCL rose under a liberal ideological framework, those attracted to its ranks possessed common liberal ideological traits and recognised the impossibility of achieving the overthrow of Apartheid through non-violent means. Also, those gravitating to the NCL also tended to harbour a deep suspicion of the South African Communist Party and its relations with the Soviet Union. They were after all “Liberals” and not “Communists” – there s a very big ideological difference between two (a difference which did not matter to the Nationalists and its Anti-Communist Act).

Importantly, a further common theme within the party was the firm belief that acts of sabotage should not bring any harm to human life, which resonated with their liberalist ideological stance. The NCL was non-racial in character, although its membership was predominantly White. The organisation hoped to attract an African following by undertaking acts of sabotage against government installations and institutions.

The NCL attracted three groups of ‘Liberals’ to its ranks: members of the Liberal Party of South Africa (the largest grouping), the African Freedom Movement (AFM) – made up of disillusioned African National Congress (ANC) members not joining MK, and the Socialist League of South Africa (SLA) – made up of disillusioned South Africa Communist Party (SACP) members – liberal thinking ‘Trotskyites’ who also did not want to join MK and its SACP alliance.

Regional Committees of the NCL were to operate autonomously in the process of recruiting members and undertaking sabotage campaigns. Between 1962 and 1963 the NCL focused predominantly on recruiting people from across the country. In mid-1962 Adrian Leftwich of the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) joined the organisation and became one of its leading figures. NUSAS was the student union present on most ‘English’ university campuses. Other people recruited into the NCL included Randolf Vigne, the vice chairman of the Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA), who joined the NCL after he was recruited by John Lang.

Other members recruited to the organisation included Neville Rubin, Baruch Hirson, Stephanie Kemp, Lynette van der Riet, Hugh Lewin, Ronald Mutch, Rosemary Wentzel, Dennis Higgs and Alan Brookes – several of them from the LPSA. With the recruitment exercise gathering momentum, the NCL established two regional committees – in Cape Town and Johannesburg, cities that provided bases as well as targets for sabotage campaigns. The NCL also had members in Natal, notably David Evans and John Laredo.

Here’s another inconvenient truth, the formation of the NCL armed resistance to Apartheid pre-dates the formation of Poqo and ‘umkhonto we sizwe’ (MK) the only difference is that the NCL did not officially announce its existence until 22 December, five days after MK announced its existence. However the fact the NCL was the ‘Prima’ (the first) anti-apartheid armed resistance movement is conveniently left out of the modern ANC narrative and they barely if ever get a mention.

The NCL initially involved itself with smuggling people out of South Africa into exile, this included helping the ANC smuggle Robert Resha out to Botswana. The ANC reciprocated by helping Milton Setlhapelo of the NCL move from Tanzania to London.

With the formation of MK, the NCL again approached MK through Rusty Bernstein to organise joint operations. After one failed operation, the relationship did not last and the two organisations ceased to cooperate again.

NCL Military Operations

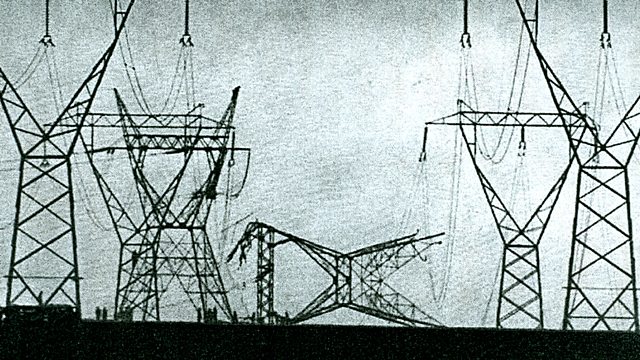

Destroyed Electricity Pylon – Photo Drum Magazine

Subsequent to his release from prison, John Lang began sourcing financial support for the NCL. He contacted Leslie Rubin – a member of the LPSA and a Ghanaian resident – to source funds from the Ghanaian government – which were given in two financial payments in 1961 (incidentally the NCL was the first armed resistance group to get finance from Ghana, the ANC and PAC came later). With money to buy weaponry and explosives the NCL were ready to go.

In 1961 the NCL sabotage campaign commenced with the targeting of three power pylons and the burning of a Bantu Affairs office.

By 1962, the was also stealing dynamite from mines for further operations. Dennis Higgs and Robert Watson, a former British Army officer, provided explosives training to members of the NCL in Cape Town and Johannesburg. In August and November 1962, the NCL carried out sabotage attacks on pylons in Johannesburg, bringing one down.

In Durban, the members of the NCL failed to bring down a pylon as a result of faulty timers. Later, in August 1963, the NCL made two attempts to sabotage the FM tower in Constantia, Cape Town. On the first attempt, the operation was cancelled after Eddie Daniels lost his revolver, which was found a few days later. In the subsequent operation at the same installation, the bomb failed to explode. Later, in September, explosives planted by the NCL damaged four signal cables at Cape Town railway station, and in November an electricity pylon was brought down.

African Resistance Movement (ARM).

It stands to reason that members of NCL quickly became wanted by the apartheid state, Myrtle and Monty Berman were banned by the government and in 1961 the police searched Lang’s residence where letters requesting financial assistance were seized. On 26 June 1961, Lang fled South Africa and went into exile to London, where he continued with anti-apartheid activities on behalf of the NCL. That same year, Monty Berman violated his banning order and was given a three-year suspended sentence. As a consequence, he was forced to leave the country in January 1962. His departure threw the NCL into disarray, and morale among the remaining members declined.

The NCL’s efforts to revitalise itself through discussion documents also failed to yield positive results. In an attempt to reinvent itself, the organisation changed its name in from the NCL to the African Resistance Movement (ARM). ARM launched its first operation in September 1963.

From September 1963 until July 1964, the ARM bombed power lines, railroad tracks and rolling stock, roads, bridges and other vulnerable infrastructure, without any civilian casualties. ARM aimed to turn the white population against the government by creating a situation that would result in capital flight and collapse of confidence in the country and its economy.

In Johannesburg, a cell of the ARM also carried out more attacks in September and November 1963. NCL members used hacksaws to cut through the legs of a pylon in Edenvale, which led to a blackout in Johannesburg’s eastern suburbs. More attacks on pylons were carried out in January and February 1964. The climax of the ARM campaign came in June 1964 when five pylons were destroyed; three around Cape Town and two in Johannesburg.

On 12 June 1964 ARM issued a flyer by way of a statement announcing its existence and committed itself to fighting apartheid and it read in part:

“The African Resistance movement (ARM) announces its formation in the cause of South African freedom. ARM states its dedication and commitment to achieve the overthrow of whole system of apartheid and exploitation in South Africa. ARM aims to assist in establishing a democratic society in terms of the basic principles of socialism. We salute other Revolutionary Freedom Movements in South Africa. In our activities this week we particularly salute the men of Rivonia and state our deepest respect for their courage and efforts. While ARM may differ from them and other groups in the freedom struggle, we believe in the unification of all forces fighting for the new order in our country. We have enough in common.”

Fighting talk no doubt.

Some inconvenient truths

So, here we have a mainly ‘white’ militant ‘terrorist’ group operating in the 1960’s blowing stuff up in resistance to Apartheid South Africa – now how many South Africans today know about that little inconvenient truth.

Here’s also another inconvenient truth, even the Black armed resistance movements like MK were led and advised by white WW2 military veterans. So much so that it even manifested itself in three of the MK’s most notable attacks – the bombing of Sasol, Wit Command and Koeberg all had ‘White’ cadres involved in them. In fact in the case of Wit Command and Koeberg they were led solely by White insurgents.

So, the basic truth is the ‘white liberals’ created their own armed resistance movements – at the same time as the ANC formed their armed resistance movement (MK), and this White armed insurgency was working in parallel with but separately to MK.

There is more inconvenient truth to come with regard ARM, and his name is John Harris, now not too many have heard of him – and many should.

John Harris

Frederick John Harris (known as John Harris) was born in 1937. He was a teacher, a member of the executive committee of the Liberal Party in the Transvaal, as well as a Chairman of the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee. He was also one of the members of the nearly all-white African Resistance Movement (ARM) and the first and only white man to be hanged for a politically inspired offence in the years after the 1960 Sharpeville emergency.

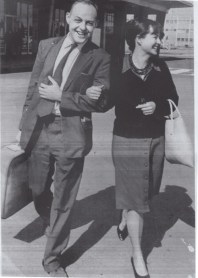

John and Ann Harris, 1963. John Harris seen here was on his way back from testifying at the International Olympic Committee on behalf of SANROC.

John Harris was banned in February 1964, a few months before police moved to smash the underground ARM. While maintaining his Liberal Party connection, he had joined ARM, but he was not arrested in the police swoops. He then decided that a dramatic gesture was needed to “bring whites to their senses and make them realise that apartheid could not be sustained”.

On July 24, 1964,John Harris walked into the Johannesburg railway station and placed a small explosive charge and several containers of petrol in a suitcase on the main ‘whites only’ concourse. On the case he left a note: “Back in 10 minutes”

It exploded just 13 minutes later, injuring several people seriously, in particular Glynnis Burleigh, 12, and her grandmother, Ethel Rhys, 77. Mrs Rhys died three weeks later from her injuries. Glynnis, who had 70% and third degree burns, was left with life-changing injuries.

A telephone warning had been planned so the station could be evacuated of civilians, but the warning was too late to prevent the explosion, and the result off this ARM action produced a horrified reaction amongst the white population – ARM had finally killed an innocent civilian. The incident was touted by the National Party as part of a terror plot by “Communists” (not liberals). Harris was arrested, tortured and beaten. His jaw was broken in three places.

Harris was tried for murder of a civilian and by the tenets of South African law for murder received an automatic death sentence. On April 1, 1965 went to the gallows, reportedly singing “we shall overcome”.

So, there you have an anti-apartheid campaigner sent to the gallows, seldom recognised in the modern South African narrative on the ‘Struggle’ as simply put he wasn’t part of the ANC and he’s the wrong colour. It would just throw out the entire whites vs. blacks political baloney banded about with such regularity, especially when the ANC, the government and the national media settle down to praise struggle ‘martyrs’ like Solomon Mahlangu as the ‘Black’ South African hanged in resistance by the nasty ‘White’ South Africans – all in broad and convenient ‘race silo’ paintbrush strokes

The end of ARM

The state crushed the ARM and the Liberal Party, eradicating both from history. The biggest setback for ARM – the one which ultimately led to its demise was not John Harris – it came in July 1964 when the police raided the flat of Adrian Leftwich. The Police subsequently raided the flat of Van der Riet, where they found documents containing instructions on sabotage and the storage of explosives. Under torture and interrogation, the two implicated their comrades.

Police hold back crowds at Johannesburg’s Park Station after a bomb exploded on the whites-only concourse on Friday July 24 1964, killing Ethyl Rhys

Leftwich’s statements were devastating for ARM. He testified against his comrades in at least two of the trials, and as someone who had played a key role in NCL/ARM operations, his evidence was difficult to refute. Subsequently, the police raided and arrested 29 members of ARM, among them Stephanie Kemp, Alan Brooks, Antony Trew, Eddie Daniels and David de Keller – all in Cape Town. Others like Vigne, Rosemary Wentzel, Scheider, Hillary Mutch and Ronnie Mutch escaped. The security police kidnapped Wentzel from Swaziland and brought her back to stand trial in South Africa. She sought relief for her illegal abduction through the courts. Higgs was also kidnapped by apartheid government forces and challenged the legality of his kidnapping through the courts.

In the subsequent trials, Eddie Daniels was sentenced to 15 years in prison, which he served on Robben Island. Baruch Hirson was sentenced to nine years in prison, Lewin to seven years, while Evans and Laredo were sentenced to five years in prison. David De Keller received a sentence of 10 years, Einstein seven years, Alan Brooks four years, Stephanie Kemp five years, and Anthony Trew four years.

The arrest of ARM members and the flight of others into exile led to the disintegration of the organisation. However, some of its members, particularly those in exile, continued fighting against apartheid by working for anti-apartheid organisations. Hugh Lewin was appointed head of the International Defence and Aid Fund’s (IDAF) information department. Rundolf Vigne also worked closely with IDAF in Britain and travelled to the United Nations (UN), campaigning against the apartheid government. Finally, Alan Brookes, a former member of ARM played a key role in organising demonstrations against the 1969 Springbok Tour to the UK.

The End of the Liberal Party

On 3 September 1965, the government issued a notice declaring that Coloured teachers were prohibited from being members of the ‘mainstream’ political parties i.e the United, Progressive and Liberal parties.

In 1966, the government tabled the Prohibition of Improper Interference Bill, which proposed the prevention of interracial political participation. In 1968, the Bill was passed in parliament as the Prevention of Political Interference Act. Two political parties, the Progressive Party (PP) and Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA) with members across racial line were severely affected.

The PP chose not to disband but become a white’s only party to fight Apartheid via the legal parameters available to it and be a representative voice of the disenfranchised in a now dominated Nationalist Parliament (eventually the PP became the Progressive Federal Party i.e. PFP which has now morphed into the modern-day Democratic Alliance – the DA), while the LPSA chose to disband rather than comply with legislation that went against its defining principle of non racialism. Between April and May 1968, meetings were held in various parts of the country, bringing to end 15 years of anti apartheid struggle by the LPSA.

White ‘Privilege’?

So where does the ‘white privilege’ gained from Apartheid enter into all this resistance to Apartheid by White people? By the beginning of the 1970’s – at least according to the Nationalist government White resistance was no more, the Whites were all on their side now. By this stage any dissonance from the White community had been effectively crushed by the Apartheid State, like it ruthlessly crushed all movements – including the Black led ones. It might be worth pointing out that by the time the Liberal Party and NCL/ARM were crushed, so too were the ANC and MK, as they were also relatively small by 1970 – it was the 1976 Soweto Uprising and thousands of ‘Seventy Sixers’ – new youth – joining MK which were to rejuvenate and boost the MK to a significant degree.

So, leading White figures not in step with the National Party imprisoned, in exile or gagged – future opponents now under the threat of the anti-communism act – sorted, no more criticism of Apartheid from the whites and all the whites can now benefit from the grand Apartheid Scheme.

No so, although the ‘white armed insurgency’ was officially dead, well into the late 70’s and 80’s saw tens of thousands of White students from the ‘white English’ universities on active protest – Natal, Wits, Rhodes, UCT, a more ‘peaceful’ resistance sprang up in all directions in all manner – locally and internationally – from the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), the United Democratic Front (UDF), the End Conscription Campaign (ECC), the Council of Churches, the Black Sash, The Progressive Federal Party, Jews for Social Justice, The South African Congress of Democrats, Temple Israel and many many more.

We are not even going to start on the Anti-Apartheid activities of whites like Bram Fischer, Helen Suzeman, Harry Shwartz, Helen Zille, Breyten Breytenbach, Andrè Brink, Beyers Naudé, Rick Turner, Michael Harmel, Ruth First, Denis Goldberg, Albie Sachs, Ben Turok, Harold Strachan, Hilda Bernstein, Rusty Bernstein, Arthur Goldreich, Helen Joseph, Colin Eglin and Rica Hodgson – even other martyred ones like Neil Aggett, Ruth Slovo and David Webster. Then there is the entire Alternative Afrikaans rock music movement to consider in its resistance to Apartheid, the Voëlvry Movement – people like James Phillips, Koos Kombuis and Johannes Kerkorrel. The list goes on.

The ‘fatal’ 1992 Referendum

In the strange world of the National Party, where “Communism” equated with ‘Liberalism” – the Nationalists made a fatal error. Feeling confident that their hated nemesis ‘Communism’ no longer really posed a threat to their idea of the ‘Western World’ democracy when the Berlin Wall collapsed in 1989 with the resultant beak up of the Soviet Union. Feeling more confident that with the loss of its ‘communist’ backers the ANC plans as to a socialist communist take-over of South Africa would now not be possible and they would be in a position to ‘talk’. The National Party was on the ascendancy in terms of ‘seats’ in Parliament in 1989 using more gerrymandering and with the SADF enjoying 5% GDP spend (the average spend of a NATO country on the military is 2% GDP) they were now more powerful than ever – they now even felt confident that with a negotiated settlement with the ANC they had a shot at a sustained political future for themselves. They had started Apartheid, but now they would rather magnanimously end it and all would be forgiven.

So when they hit internal political hiccups and resistance from within their party, coupled with resistance from the ‘all white’ Conservative Party and Afrikaner extreme right (AWB) – and with the ANC not really rolling over in the negotiations. They made the fatal error of thinking they needed ‘populist’ support and put forward what was to become the last ‘whites only’ vote on the issue of Apartheid. But instead of a party political vote where they had a constitutional seat advantage which would see them over the line, FW de Klerk instead opted for a ‘one to one’ count, a ‘one man one vote’ all white referendum. For the first time since 1948 it would become clear again who in the white community supported Apartheid and who didn’t, and this time constitutional boundaries were moot.

The Nationalists for the first time sided with the ‘liberal white ‘left, it backed the support to end Apartheid and joined forces with the ‘Democratic Party’ (the newly reformatted PFP which had nearly folded along with the Liberal Party in 1965) – it would spell out just how many liberty loving white South Africans there were to vote ‘Yes’ to end Apartheid – the nearly 3 million strong white voter base brought back an astonishing result. 69% of whites wanted the end of Apartheid – nearly 2,000,000 whites (read that again – 2 million whites willingly and very peacefully voted to end what is now incorrectly touted as their ‘Apartheid privileges’).

In terms of demographics this was not really too dissimilar to the split faced by Jan Smuts in 1948 – the populist white vote was still very much an anti-apartheid vote, even 40 years on. The only difference between 1948 and 1992 was the fact the white electorate base had grown to three times that of 1948 and an armed struggle had kicked off in the interim.

The truth of the matter is that an armed struggle did not really end Apartheid, the ballot did. There was no MK led ‘military victory parade’ over defeated SADF/SAP forces – and that’s because there was no military victory. The victory in the end was a moral one, and it was one in which democracy loving white South African’s played a key role – the first time white people were given proper representation and voice by weight of sheer numbers – and they voted Apartheid and the nationalists out – that is a fact.

The ‘Yes’ vote spelled the end of the National Party, it had fundamentally misinterpreted its support. It’s voting base was fractured further after the 1994 Democratic elections and it continued to diminish until one day it did an unbelievable thing – after flirting with old ‘white’ enemy – the Liberals – in a Democratic alliance they then closed shop, left the Liberals and walk the floor in April 2005 and joined the ranks of none other than the African National Congress (ANC) – their much hated ‘Communists’. So much for Afrikaner Nationalism and the visions of Malan and Verwoerd – because the inconvenient truth is that this is what they are left with as a legacy.

In Conclusion

Nelson Mandela said – “there is no such thing as Black and White” and on this part he’s right. The armed struggle to end Apartheid was not a clear cut Black vs. White campaign. It was also a White vs. White and even a Black vs. Black struggle. The Apartheid Struggle was a struggle of normal decent democratic, human rights loving liberal people – black and white – against the forces of a very small white supremacist movement – a movement which did not even have the support of the majority of White South African people, and which by sheer luck and circumstance managed to get into power and then hung on to power using jackboot styled oppression – of all South Africans – the Black, Indian and Cape Coloured communities and large sectors of the White community too.

However since Mandela’s passing the ANC (and in later days the Economic Freedom Front and ‘Black Lives First’ movements) have worked hard to reinvigorate the struggle and reinvent it as a Black versus White issue – this been done because ANC corruption has so raped the country of its resources now, in not only ‘state capture’ but also in base municipal services – and as the ANC and its cabal collapse on itself they strike out to all White people in South Africa to give up a mythical concept of ‘white’ capital and ‘white owned’ farmland and continue to feed their corruption – Whites are to pay for their collective sins of Apartheid and their collective ‘white privilege’. It is all based on misconstrued history and as a result can be dismissed as utter hogwash, nothing more than party political rhetoric and nothing to do with historic fact at all.

The ANC in recent times is even audacious enough to say that it was only really their struggle to end Apartheid. Movements supported by White South Africans – like the Torch Commando, and the Liberal Party and its African Resistance Movement (ARM) are completely written out of the narrative – lost to history, to the point that not many South Africans today are even aware of them – where the National Party sought to eradicate them from the party political scene during Apartheid, the African National Congress in the Post-Apartheid political scene refuses to acknowledge them as well – literally dismissing thousands and thousands of ‘whites’ who did not support Apartheid and the ANC are very happy to keep this history buried – it contradicts their rhetoric and narrative that much.

Hendrik Verwoerd after he was shot in the head by David Pratt using a .22 revolver

Can you imagine the ANC standing up and thanking people like Sailor Malan for mobilising hundreds of thousands of white South Africans against Apartheid in his Torch Commando, or thanking the Springbok Legion for providing the mainly Jewish trained soldiers who helped start Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) or thanking and the members of the Liberal Party for their predominantly ‘White’ equivalent of MK, the NCL/ARM and their martyr to the cause, John Harris – it won’t happen. The revolver used by David Pratt to attempt to assassinate Prime Minister H.F. Verwoerd has not made it into the exhibits of the Anti-Apartheid museum as an icon of resistance. Instead the ANC are very happy to keep it in its dusty evidence box in an archive.

Given the Economic Freedom Front (EFF), Black Land First (BLF) and ANC’s current rhetoric, the truth is in the hard work pile – it would be very hard to imagine these organisations thanking the white community. What this ANC/EFF/BLF effort to re-establish race divide and deepen South African race politics has done – is force articles such as this one, which instead of taking about the general collective in a fight between dark and light and moving on with our young democracy, we are now almost forced to highlight the ‘White’ resistance to Apartheid, and historically point out it was not just a couple of ‘white liberals’ here and there – but hundreds of thousands of white South Africans over the course of four decades who resisted Apartheid, by ballot and some even by the gun.

Its bad enough that the ‘White’ conscripted statute military veterans are demonised and vanquished by the ANC ruling party and its aligned political affiliations, but it is with extreme irony that the ‘White’ veterans of the non-statute ‘struggle’ forces are now also completely ignored, not often thanked at all and out in the cold – no real effort to erect statues to them of name roads or airports in their honour – that would mean recognising white resistance to Apartheid.

So, it’s just another indication of Apartheid in reverse, the manipulation of history to suit a party political narrative – let’s face it, the last thing the ANC or EFF wants is for young Black South Africans to make heroes out of Apartheid era ‘White’ South Africans and recognise the white community’s struggle against Apartheid.

It’s suits them to trivialise the ‘white struggle’ as somehow insignificant, and they leaned this from the ‘masters’ – the National Party blazed the way by trivialising Jan Smuts, Sailor Malan, just about every South African military hero from WW2 and the entire ‘white’ Liberal Movement. They especially snubbed any white Afrikaans people resisting Apartheid – positioning these people as somehow ‘insignificant’, deviants of the ‘pure’ Afrikaner cause and traitors to their own nation – certainly not to be worshipped by Afrikaner youth, they buried their collective anti-apartheid legacy using a combination of unrelenting propaganda and quite literally writing them out of ‘national christian curriculum’ school history books. The net result is felt even today- the historical narrative of a broad group of ‘Afrikaners against Apartheid’ does not exist.

In the end, political inspiration and not historical fact will ensure this entire saga of ‘white’ resistance to Apartheid remains an unknown and inconvenient truth. It was as inconvenient to the Afrikaner Nationalists then as it is to the African Nationalists now.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

Related work and links:

Tainted versus Real Military Heroes: Tainted “Military Heroes” vs. Real Military Heroes

Sailor Malan: Sailor Malan; Fighter Ace & Freedom Fighter!

References:

South African History On-Line (SAHO) – articles on Liberal Party, Alan Paton, African Resistance Movement, Torch Commando and Liberal Party of South Africa. Dick, G. 2010. John Harris: Hardly a Martyr (Online). Gunther, M. The National Committee of Liberation (NCL)/ African Resistance Movement, in The Road to Democracy in South Africa: 1960-1970. Cape Town: Zebra Press. Large extract from SA History On-Line – The African Resistance Movement (ARM): An Organisational History. Large extracts and references from “Eighteen times white South Africans fought the system” and Opening Mens Eyes; Peter Brown and the Liberal Struggle for South Africa by Michael Cardo. Video copyright Verwoerd – Associated Press

Pingback: Tainted “Military Heroes” vs. Real Military Heroes | The Observation Post

Pingback: The truth behind the bombing of Witwatersrand Command | The Observation Post

I was one of the original members of the Torch Commando

I still have the documents from the first annual general meeting

LikeLike

While appreciating this particular blog, sadly you neglect to mention the Black Sash (nor many other women). The ongoing determination of the Black Sash (which included members from varying political parties) led Nelson Mandela to mentioned the organisation in his first speech post his release, as I am sure you are aware.

LikeLike

Hi Gille. This article forcussed on the military organisations and how they evolved. I did however the ‘white’ led civilian organisations, including the Black Sash and white ‘struggle’ .leaders.

LikeLike

Pingback: A ‘road’ to democracy called Colin Eglin | The Observation Post

This is a useful (if distorted) summary of some of our history. Of course there were whites who resisted apartheid. From the earliest days and right to the end. However, the ideological position taken here, that more whites opposed apartheid from the outset when the NP came to power in 1948 to the end when De Klerk unbanned organisations and individuals in 1990, is rather shaky. What makes me most uncomfortable though, is the usual dividing us into opposing race groups and pointing racial fingers. Until we can all recognise that we’re firstly Africans and South Africans and have a common destiny which we have to work out with each other, we will continue to perpetuate the injustices and distortions of the past.

LikeLike

Hi Louis, thank you for your input. I’ve done a lot of work on the Torch Commando and Sailor Malan and thier links to the Liberal Party and eventually the feeding of their fire-brand members to the MK and ARM respectively. Its a part of South African history is remains unknown to many. As to idological isses, upfront I explained that if it was not for modren 2018 South African leaders and politics dividing the issue now into ‘settlers’ (or lately ‘invaders’) and foreigners to Africa, such a homogeneous definition of us all been ‘Africans’ becomes moot in thier eyes – and it has literally forced an article like this to be written to remind them that the struggle against Apartheid was not a race one, nor was it strictly a ANC one.

LikeLike

Pingback: SOUTH AFRICA: Exile & Draft Resistance 1957-1993 | prisonwarresisters