For the most part of the Rhodesian Bush War (July 1964 to December 1979), Rhodesia did not have any battle tanks. As far as armour went they had armoured reconnaissance vehicles and armoured personnel carriers (APC) but did not have an armoured battle tank to speak of. Prior to the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in November 1965 the Bush War which waged in Rhodesia was very low-key, small insurgency groups were relatively easily dealt with by Police and Army personnel in ‘soft skinned’ trucks and Land Rovers to ferry troops to the contact zones. Britain, as Rhodesia’s primary military partner, saw no reason to send tanks to Rhodesia, the conflict at that stage simply did not demand such a vehicle.

After UDI, the Bush War gradually escalated and Rhodesia was simply left with no battle tanks and had to make do with small Ferret and Eland 90 armoured cars and a home-grown industry adapting and making all sorts of V-shaped hull armoured vehicles to protect troops from landmines and any sort of small arms assault. Innovative as ever during the war the Rhodesians literally made do with using anything they had at their disposal.

After UDI, the Bush War gradually escalated and Rhodesia was simply left with no battle tanks and had to make do with small Ferret and Eland 90 armoured cars and a home-grown industry adapting and making all sorts of V-shaped hull armoured vehicles to protect troops from landmines and any sort of small arms assault. Innovative as ever during the war the Rhodesians literally made do with using anything they had at their disposal.

Big punching battle tank armour in support of these operations the Rhodesians did not have. Untill the South Africans gave them an unexpected gift, and it was not South African ‘Elephant’ battle tanks (adapted British Centurion tanks with Israeli tech), nope, this gift was the property of Libya.

If you have not declared war on that country it’s a brazen step to give that country’s battle tanks to another country without even paying for them in the first place – so let’s have a look at how Rhodesia landed up with some of Libya’s Polish built Soviet T-55 Tanks originally destined for Uganda and re-directed to Rhodesia courtesy of South Africa.

Libya’s Polish built Soviet T-55 Tanks in Rhodesia, seen here still in their Libyan Army camouflage scheme.

This one reads as an International who’s who in the world of ‘terrorism’ and the world of ‘international intrigue’ surrounding it. It also leaves a big ‘what if’ question.

Confiscated

In late 1979, a French flagged cargo ship, the ‘Astor’ rounded South Africa’s cape transporting a heavy weapons consignment from Libya, destined to support Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda.

Field Marshal Idi Amin

Earlier in 1978, Idi Amin’s support had waned, Uganda’s economy and infrastructure had started to collapse, by November 1978 this general demise of Amin’s authority came to a head when a contingent of Ugandan troops and officers mutinied. True to form for a dictator Amin sent troops against the mutineers, some of whom had fled across the Tanzanian border. No problem to Amin, he had vengeance in mind and had to stamp his absolute authority, so he promptly accused Tanzania of waging war against Uganda, and he then invaded and annexed a section of Tanzania.

Tanzania counterattacked alongside rebel elements of Uganda’s army not happy with Amin. Uganda found itself in a war with a neighbouring state and in need of as much military armour and equipment it could lay his hands on.

As dictators go, a fellow ‘Muslim’ African dictator, ‘Colonel’ Muammar Gaddafi of Libya was right behind ‘Field Marshal’ Idi Amin and elected to support Uganda with military equipment including ten of Libya’s surplus stock Polish built (made in 1975) Soviet T-55LD tanks. The tanks, which including assorted ammunition and spare parts for them were to be offloaded at Mombasa, Kenya, and from there transported overland to Uganda.

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi

The tanks would never get to Uganda, whilst docked in Mombasa the crew of the Astor received the belated news of Uganda’s defeat in the Uganda-Tanzanian War and received new orders for their cargo. Instead of Uganda, Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, now well-known for its support of international terrorism and destabilising African states in countenance to its ideology, felt that the next best use for their tanks would be the Angolan War in support of the Communist and Cuban aligned MPLA.

The freighter with its cargo of Libyan owned T-55 Soviet tanks turned around and re-entered South African waters on its way to Angola. The Astor’s unexpected return to South African waters on its way to Angola with the same manifesto and its subsequent call into Durban port in October 1979 aroused suspicion from the South African Navy and Port Authority.

South African port authorities then boarded and seized the French freighter and its cargo of Libyan T-55 tanks.

Total Onslaught

By late 1979 P.W. Botha’s position on maintaining Apartheid South Africa had started to take shape and in particular his ideas of ‘Total Onslaught’ of Communism to bring about ‘Total War’ against it. South Africa had never officially declared war against Angola, yet it was at war with Angola – and even fighting in Angola. It was also at war with ‘terrorism’ and ‘communism’ and saw itself as aligned to the ‘west’ in the Cold War against Communism. In this respect, like the USA, it also regarded itself at war with ‘terrorist states’ – Muammar Gaddafi not only sponsored all sorts of communist insurgency (anti Colonial) in Africa, he also backed the African Nation Congress (ANC).

The tanks were now headed to Angola, and therefore posed a significant threat to the South African Defence Force fighting a proxy war against the MPLA and Cuba in Angola. So as to South Africa’s position, the Libyan tanks qualified as ‘war booty’ and ‘fair game’ – and insofar as international law goes they simply broke it and confiscated all ten of Libya’s tanks.

Keen on understanding and testing Soviet armour and technology for weaknesses and advantages, two of the tanks were kept by the South African Army. The remaining eight were transported to Rhodesia, together with SADF advisers for the purpose of training Rhodesian crews. But why Rhodesia?

P.W. Botha and his Cabinet

As to Botha’s fears of total onslaught, by October 1979 the Rhodesian bush war had entered its final phases of negotiated settlement. As early as March 1978, The Rhodesia Agreement put the now ‘Zimbabwe-Rhodesia’ into a transitional power-sharing state. On 1 June 1979, Josiah Zion Gumede became President. The internal settlement left control of the military, police, civil service, and judiciary in white hands, and assured whites about one-third of the seats in parliament. It was essentially a power-sharing arrangement between whites and blacks. However ZANLA (ZANU) and ZIPRA (ZAPU) factions led by Robert Mugabe and Josuha Nkomo respectively denounced the new government as a puppet of ‘white’ Rhodesians and fighting continued. Later in 1979, the British, and Margaret Thatcher’s government called a peace conference in London to which all nationalist leaders including ZANU and ZAPU were invited to find a solution.

This led to an unsettled state of affairs, and to Apartheid South Africa and PW Botha it was imperative that Zimbabwe-Rhodesia remained a ‘friendly’ state and not another hostile neighbour from which insurgencies into South Africa could be launched. It was in South Africa’s interests that the Rhodesian Army maintained an operational readiness to see off ZIPRA and ZANLA attempts at military overthrow. ZIPRA’s intentions had all along been to roll into Rhodesia using some sort of conventional warfare – including their Soviet donated T-34 tanks, Mugabe’s ZANLA focused primarily insurgency warfare (terrorism) with the land-mine as their primary weapon.

Bolstering the Rhodesian Army with eight of Libya’s tanks was in South African interests, and it was not just tanks, prior to 1979 the South African Air Force and South African Army had been conducting joint operations and sharing all sorts of weaponry, technical advancement and training with the Rhodesians. In fact in September 1979 Operation Uric had just taken place, and that was a joint operation with South African Air Force Puma helicopters covertly in support of the Rhodesian ground and air forces.

Operation Uric, note SAAF Puma’s in support of the Rhodesian Army

However the South African’s were very secretive as to any of their military involvement in Rhodesia and did not want the international spotlight on Rhodesia drawn to them in any way, and a lot had to do with the National Party generally not wishing to have anything to do with the British and a wish to have the ‘friendly’ ‘Black’ neighbouring states like Botswana and Zambia leaving them alone. South Africa’s ‘official’ policies towards Rhodesia had blown hot and cold from 1975 onwards, whereas covertly they maintained involvement in the Rhodesian Bush War, mainly in the form of South African Police personnel and later with South African Air Force aircraft and personnel. As part of their ‘sanctions-busting necessities the Rhodesian Armed Forces also acquired South African military hardware and ‘advisors’ on its use from South Africa.

To the above need to keep out the spotlight, the movement of Gaddafi’s Libyan tanks from South Africa to Zimbabwe-Rhodesia needed a cover story, so a rumour was concocted and spread to the effect that the tanks had been captured in Mozambique by Rhodesian forces.

Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment

At the on-set of the Rhodesian Bush War after UDI, the Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment consisted of a handful of aging British ‘Aden Crisis’ surplus ‘Ferret’ armoured reconnaissance vehicles and even fewer very unserviceable World War 2 era American T17 Staghounds.

As the Bush War progressed, although aging, the Ferrets remained operational in a counter insurgency role, equipped with a single heavy machine gun, Browning medium machine guns, or a 20mm Hispano-Suiza HS.820 anti-aircraft gun, In addition the Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment used MAP-45 and MAP-75 armoured personnel carriers (APC), for infantry support.

As the Ferret’s were aging and their firepower was limited, Eland Mk4 armoured cars were also imported in quantity from South Africa (the Eland was a South African variant of the French Panchard AML) and it was utilised for fire support and anti-tank duties when operating over the border into Mozambique and Zambia (both of whom had Soviet era battle tanks). The Eland was armed with a 90mm cannon capable of destroying a T-34 at medium range, enabling the smaller armoured cars to punch well above their weight, but the Rhodesian Army remained woefully short of battle tanks.

Rhodesian Eland Armoured Car

The remaining eight Libyan T-55 tanks offered as aid to the Rhodesian Army by South Africa, as well as a small contingent of South African Army technical advisors and armour specialists from the SADF School of Armour sent along with them were happily received by the Rhodesians, and they were assigned to a newly designated “E” Squadron in a now re-defined Rhodesian Armoured Corps.

The first intake of T-55 crews were recruited only from Rhodesian Army regulars, mainly from ‘D’ Squadron RhACR and assigned to a German Army veteran, Captain Kaufeldt, who was well versed in tank warfare. More recruits arrived from the Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) and Selous Scouts to fill the gaps.

To create the impression that Rhodesia suddenly possessed a large contingent of heavy tanks, the Rhodesians used a ‘revolving door ruse’, and E Squadron drove them all around Zimbabwe-Rhodesia on tank transporters for several months in order to give the impression to ZANLA (ZANU) and ZIPRA (ZAPU) intelligence that there were many of them.

Improvements and adaptations made to the Libyan T-55’s

Personnel assigned to “E” Squadron were trained by South African tank crews, who also modified each T-55 with an improved communications system adopted from the South African Eland Mk7. The South African headset system used a throat-activated microphone system and were far superior to the Soviet models.

Rhodesian T-55 in American camouflage scheme

Oddly, the Soviet manufactured radios on the T-55 were positioned near the gun-loader’s position and operated by the gun-loader and not the tank commander. Figuring the gun loader was not the right person to co-ordinate radio communications and already had his hands full operating the gun, the Rhodesians and South Africans removed the radio from the loader’s position and reinstalled it near the tank commander for his control and use.

On arrival the T-55’s also sported their original Libyan desert camouflage scheme. The Rhodesian’s repainted them in an American tank camouflage scheme, which was completely unsuitable to the African bush environment and finally the South African instructors had them painted again in anti-infra-red South African camouflage, which proved perfect for Rhodesian conditions.

Rhodesian T55 in the South African camouflage scheme

In a unique ‘battlefield tradition’ the Rhodesian T-55 crews kept up with their Soviet DNA irony and they were all given brand-new Soviet made AKMS assault rifles (most likely part of captured stashes of soviet armaments).

Operation’s Quartz and Hectic

The incorporation of heavy tanks into the Rhodesian Armoured Corps came a little too and too late to effect a change the Bush War, political circumstances were to over-take them, but they very nearly changed history altogether in a planned operation called ‘Operation Quartz’ along with a parallel operation called ‘Hectic’. If these two particular operations had gone ahead Zimbabwe may well have been a very different place to what we know it to be now.

The Lancaster House Agreement was already in its final phase by the time Zimbabwe-Rhodesia received its battle tanks, both Mugabe and Nkomo had already agreed to end the war in exchange for new elections in which they could participate. This General Election was scheduled in a couple of months – February 1980, and the guerilla insurgents had all ‘come in’ from the bush during the cease-fire arrangement and were at designated ‘assembly points’ under a British led commonwealth military team (acting in a transitional and oversight role – called Operation Agila) and awaiting demobilization or integration with conventional forces.

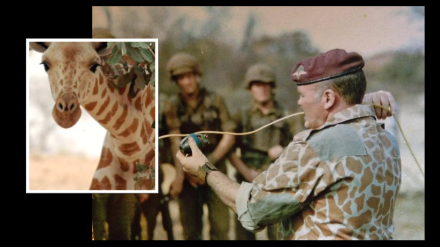

Major General John Acland, Commander of the Monitoring Force (CMF), with guerrilla fighters at an Assembly Area during the seven day ceasefire at the start of the peace process. During the ceasefire, 22,000 communist guerrilla fighters of Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and Joshua Nkomo’s Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) as well as regular soldiers of the Rhodesian Security Forces gathered at sixteen assembly areas scattered throughout the country. General Ackland acted as Military Advisor to the Governor of Rhodesia and Chairman of the Ceasefire Commission. Imperial War Museum

Operation Quartz is still shrouded in a little secrecy, but consensus amongst veterans and documents was that it was based on two slightly different assumptions, the first assumption; Mugabe would be defeated in the elections and ZANU would revert to their insurgency campaign and the war would simply continue. therefore it would be necessary for conventional Zimbabwe-Rhodesia forces to carry out a strike against ZANU irregulars and wipe them out en-masse whilst at their assembly points, so as to prevent its forces from ever attempting a coup and taking over the country by force.

The second assumption; It was obvious to all political players at the time, it would be very unlikely that Mugabe and ZANU would be defeated in the elections and if anything would still win significant seats and even if in coalition would find themselves in power anyway. In this respect, if there was sufficient electoral fraud and intimidation Operation Quartz would be given a GO and would effectively be a military Coup d’état of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. In this scenario, the ZANU guerillas now stationed at the various assembly points would be targeted by conventional Zimbabwe-Rhodesia forces and literally wiped out en-masse.

In either event, this plan envisaged placing Rhodesian troops located at strategic points from which they could simultaneously wipe out all guerilla insurgents at the Assembly Points, with specific attention to the ZANLA (ZANU) ones. The Rhodesian security forces had been tasked with monitoring the pre-election activities and keeping the peace during the election process, therefore most Rhodesian combat units were already in position within easy striking distance of the ‘assembly point’ camps. The plan also factored strikes by the Rhodesian Air Force on the assembly points to soften them up before the ground forces moved in.

‘Operation Hectic’ was a second plan underpinning Operation Quartz and this plan was to use Rhodesian SAS special forces to assassinate Robert Mugabe and ZANU leaders at their national and regional election campaign headquarters/offices.

Of the eight T-55 tanks, half of them were designated for Operation Hectic and half of them were allocated in support of Operation Quartz. Four tanks were sent to the Audio Visual Arts building of the University of Rhodesia to support the planned SAS assault on the ZANU leaders located there. The other four T-55 tanks were sent to Bulawayo to assist the RLI Support Commando in the attack planned for a large Assembly Point in the area.

The tanks were bombed up ready to go, the SAS fully prepared and tooled up for their task. As Zimbabwe-Rhodesia’s 1980 landmark elections drew to a close, the tankers, SAS and troops of the RLI and Selous Scouts waited patiently by their radio’s for the operation GO code-word “Quartz”, they were quietly ‘chomping at the bit’ – the ‘terrorists’ were in for a big surprise.

But the signal never came.

Three hours before the planned GO Operations Quartz and Hectic were cancelled and Mugabe was announced as the election’s victor, his men and their supporters jubilant in the streets and the various assembly points in the future Zimbabwe, all the while the Rhodesian troops watched them stoic and dismayed silence.

Monday March 04,1980 RhACR ‘E’ Sqn listen to ZRBC election result broadcast – Operation Quartz will not go ahead.

Some sources on Operation Quartz even point to South African involvement, which in the context that South Africa had provided the Rhodesians the T-55 tanks for the planned strike a couple of months ahead of the election carries some validity. To these sources the planned Operation Quartz strike also included Puma helicopters of the South African Air Force (SAAF) and would also involve the participation of elite Recce units of the South African army (nothing unusual in this, SAAF and SA Special Forces already had a close working relationship on Rhodesian Operations in 1979). An auxiliary plan was to allow a Battalion’s worth of South African troops into the country in order to protect the Beit bridge area, the main route of escape for Rhodesian whites should the situation degenerate into all-out war.

What if?

The Libyan T-55 tanks gifted to Rhodesia by South Africa never fired a shot in anger, the Rhodesian military powers deeming that Mugabe’s win in an election overseen by Britain and other international powers was legitimate, and a military Coup d’état of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia by the Rhodesian Armed Forces General’s and officer elite would not have lasted long and in all likelihood there is some truth to that. Hitting ‘cease-fire’ assembly points under British Military oversight would never have ended well. But, had it happened, it does ask the question whether a Mugabe free Zimbabwe today would have been an infinitely better place?

Robert Mugabe at the height of his Presidency

It also asks what South Africa’s role would have been should the Rhodesian Bush War have ramped up to a whole new level or if a newly reconstituted Rhodesia remained ‘friendly’ to Apartheid South Africa with a closer relationship – could the Apartheid Nationalists have held on for longer against international pressure? The assassination of Mugabe and his team, and stumping his forces en-masse is the sort of hypothetical question along with historical hindsight many can ask, it’s up there with what would have happened to Germany should Adolph Hitler and his Nazis have been removed sooner.

In the end we’ll never know, but of the T-55 battle tanks today one of the original 10 seized by South Africa is now found at the South African War Museum in Johannesburg (in Libyan desert camouflage) and it stands as a permanent reminder to ‘what if?’

Researched and written by Peter Dickens

References include The Rhodesian Armoured Car Regiment on-line. Operation Quartz – Rhodesia 1980 by R. Allport. The Mukiwa – Operation Quartz on-line. Operation Quartz: Zimbabwe/Rhodesia on the brink – Peter Baxter History.

Related links:

Operation Uric; Joint South African/Rhodesian Ops & the loss of SAAF Puma 164

The Operation was Modular, the battle ground was the Lomba River in Angola and Commandant Kobus Smit was the Operational Commander in charge of the SADF’s 61 Mechanised Battle Group. Three combat groups – Alpha under the Command of Cmdt Kobus Smit himself, Bravo under the command of Cmdt Robbie Hartslief, Charlie, under command of Maj Dawid Lotter. All supported by 20 Artillery Regiment (Cmdt Jan van der Westhuizen) – Papa battery from 32 Battalion, Quebec battery from 4 SAI and Sierra battery from 61 Mech Battalion Group.

The Operation was Modular, the battle ground was the Lomba River in Angola and Commandant Kobus Smit was the Operational Commander in charge of the SADF’s 61 Mechanised Battle Group. Three combat groups – Alpha under the Command of Cmdt Kobus Smit himself, Bravo under the command of Cmdt Robbie Hartslief, Charlie, under command of Maj Dawid Lotter. All supported by 20 Artillery Regiment (Cmdt Jan van der Westhuizen) – Papa battery from 32 Battalion, Quebec battery from 4 SAI and Sierra battery from 61 Mech Battalion Group.

Major Hannes Nortman from 32 Battalion arrived on the battle scene at the Lomba on the morning of 10 September, the ZT3 Ratel, code 1-2, one of 32 Battalion’s ZT3’s had taken up position under the initial command of Lt Ian Robertson, Lt Robertson was injured when he jumping out of the ratel to give fire guidance to the 90mm Ratel next to his ZT3 Ratel. Unfortunately, he landed at the same spot as one of the incoming mortars and took a large piece of shrapnel in his head. The crew of the ZT3 were busy with the casevac of their injured commander, when three T55 Soviet made, heavily armoured enemy tanks rolled up. Major Hannes Nortman came running up, taking charge of the ZT3 Ratel 1-2 and the attack.

Major Hannes Nortman from 32 Battalion arrived on the battle scene at the Lomba on the morning of 10 September, the ZT3 Ratel, code 1-2, one of 32 Battalion’s ZT3’s had taken up position under the initial command of Lt Ian Robertson, Lt Robertson was injured when he jumping out of the ratel to give fire guidance to the 90mm Ratel next to his ZT3 Ratel. Unfortunately, he landed at the same spot as one of the incoming mortars and took a large piece of shrapnel in his head. The crew of the ZT3 were busy with the casevac of their injured commander, when three T55 Soviet made, heavily armoured enemy tanks rolled up. Major Hannes Nortman came running up, taking charge of the ZT3 Ratel 1-2 and the attack.

This headgear was usually a M1963 SADF steel helmet, known as a ‘staaldak’ painted red or the helmet’s plastic detachable ‘inner’ called a ‘doiby’ or ‘dooibie’ also painted red. It was issued to anyone whose behaviour or actions were deemed undisciplined in the old South African Defence Force (SADF) system and they were ‘Confined to Barracks’ (CB) or given ‘CB Drills’.

This headgear was usually a M1963 SADF steel helmet, known as a ‘staaldak’ painted red or the helmet’s plastic detachable ‘inner’ called a ‘doiby’ or ‘dooibie’ also painted red. It was issued to anyone whose behaviour or actions were deemed undisciplined in the old South African Defence Force (SADF) system and they were ‘Confined to Barracks’ (CB) or given ‘CB Drills’.

After UDI, the Bush War gradually escalated and Rhodesia was simply left with no battle tanks and had to make do with small Ferret and Eland 90 armoured cars and a home-grown industry adapting and making all sorts of V-shaped hull armoured vehicles to protect troops from landmines and any sort of small arms assault. Innovative as ever during the war the Rhodesians literally made do with using anything they had at their disposal.

After UDI, the Bush War gradually escalated and Rhodesia was simply left with no battle tanks and had to make do with small Ferret and Eland 90 armoured cars and a home-grown industry adapting and making all sorts of V-shaped hull armoured vehicles to protect troops from landmines and any sort of small arms assault. Innovative as ever during the war the Rhodesians literally made do with using anything they had at their disposal.

Once we stole his Old Brown Sherry and quickly owned up. Then tried to make him open us another bottle, on religious principle. Instead he cocked his rifle and gave us some Old Testament vengeance.

Once we stole his Old Brown Sherry and quickly owned up. Then tried to make him open us another bottle, on religious principle. Instead he cocked his rifle and gave us some Old Testament vengeance.

Yes, Christo’s GrootBoet had a Milky Way of pips on his shoulders. He was so important he only moved by Helicopter. Christo said he even flew to the GoCarts on the other side of his Base.

Yes, Christo’s GrootBoet had a Milky Way of pips on his shoulders. He was so important he only moved by Helicopter. Christo said he even flew to the GoCarts on the other side of his Base.

Such diplomatic protesting fell on deaf ears within the South African Navy strike-craft circles as they saw intelligence gathering in South African waters and demonstrations of fighting prowess as their job to do, and all the diplomatic ‘ballyhoo’ simply reinforced their legacy as an elitist naval force and in fact another reason to hold up their heads in pride. So all in all, given the political circumstances of the time, the South African Navy strike personnel felt they did a great job.

Such diplomatic protesting fell on deaf ears within the South African Navy strike-craft circles as they saw intelligence gathering in South African waters and demonstrations of fighting prowess as their job to do, and all the diplomatic ‘ballyhoo’ simply reinforced their legacy as an elitist naval force and in fact another reason to hold up their heads in pride. So all in all, given the political circumstances of the time, the South African Navy strike personnel felt they did a great job.