There is something deeply disturbing when you read about the ‘last soldier to die’ in a war, it’s a complete sense of futility, a young life that is snuffed out for this or that political conflict. The South African Border War (1966 – 1989) along the now Namibian border with Angola carries with it the same sense of pointlessness when you read about the first soldier lost and the last soldier lost as it was with the 1st World War.

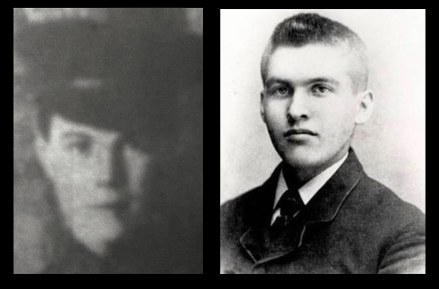

Pvt Parr (Left) and Pvt Ellison (Right)

During World War 1, the first British soldier to die was Private John Henry Parr on 21st August 1914, Killed in Action near Mons – Belgium. The last British serviceman to die in WW1 was Private George Edwin Ellison, killed in action near Mons – Belgium on Armistice Day itself – 11 November 1918. The irony, both died in a foreign country and they are buried in the same graveyard in Belgium facing one another – a few meters separate them. The futility, for 4 years millions of more casualties separate them, in the end – all with no tangible military ‘gain’.

One cannot avoid thinking whether this same sense of waste of young life has a parallel in the South Africa’s Border War on the Namibian/Angola border. The sad truth is that it does.

Lieutenant Freddie Zeelie from 1 Reconnaissance Regiment is regarded as the first SADF combat casualty of The Namibian Border War. Killed in Action on 23 June 1974 while engaged on anti-insurgent operations in Southern Angola. On hitting contact with insurgents he bravely stormed their machine gun position regrettably losing his life in the process. He was only 22 years old.

The last soldier to die in combat in this Border War was Corporal Hermann Carstens, also from 1 Reconnaissance Regiment, Killed in Action on 04 April 1989 during fierce close-quarter fighting with a numerically superior force of heavily armed SWAPO PLAN insurgents near Eenhana. He was only 20 years old.

The irony, Lt Zeelie and Cpl Carstens both died in a foreign country – defending the same stretch of border between the same two countries – South West Africa (Namibia) and Angola, both fighting the same insurgents. The futility, for 15 years separating their respective deaths there would be thousands of casualties. In the end – all with no tangible military ‘gain’.

Lt Zeelie (Left) and Cpl Carstens (Right)

It’s a sad thought indeed, however their actions and losses are not entirely futile, as with the First World War, the Border War resulted in changed ideologies – changes which were necessary to attain peace, and our modern freedoms as we have them now is because of their sacrifice.

So let’s have a look at the ‘last’ soldier to die during the Namibian Border War’, and I must thank both Tinus de Klerk and Leon Bezuidenhout whose work this is, and who have shared it with us:

The last soldier to die in the Namibian Border War- Corporal Hermann Carstens, 1 Reconnaissance Regiment.

Written by Tinus de Klerk and Leon Bezuidenhout

Corporal Hermann Carstens, 1RR, Operators Badge and Wings on his chest

A short background: Introduction to 23 years of war, 1966–1989

South Africa administered the former German colony of German South West Africa since 1920 after the First World War (1914–1918). Initially, South Africa wanted to incorporate the territory as a fifth province of the country. The incorporation into South Africa never materialised, however, and since the 1960s more and more states wanted to declare the then South West Africa (SWA) an independent state, Namibia.

In 1966 the South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO) started an armed insurgency against the South African administrators through its military wing, the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN). The war would last for 23 years, and eventually it would also escalate into Angola and, for some time, into Zambia.

In essence, the Namibian Border War (also known as the South African Border War) became a cold war by proxy. By the early 1970s, the United Nations (UN) adopted Resolution 435 to lay the foundation for Namibian independence. By 1988 the Cold War drew to a close and the South Africans, Cubans and Angolans were ready to engage in negotiations to withdraw their troops from the SWA/Angolan border. These negotiations opened the way for Namibian independence.

One of the issues agreed upon in the trilateral negotiations was that the South African troops would be reduced to 1 500 men and would be confined to base. SWAPO would withdraw to 150 km north of the border. Resolution 435 made it clear, however, that with its implementation (which would be on 1 April 1989), SWAPO would also remain at their bases. If they therefore had established bases on SWA soil, they would also be confined to these bases. SWAPO saw this as a loophole, and secretly planned a massive invasion for 31 March/1 April 1989. The sole intention was to establish bases in northern SWA.

The South Africans, however, did not trust SWAPO, and even less so the influx of foreign troops of the United Nation’s Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG). This force would supervise the transition period and comprised peacekeepers from several UN states, including Finland, Britain, Australia, Malaysia, Pakistan and Kenya. South Africa continued operating their intelligence sources. The South West African Police (SWAPOL) and its Security Branch were tasked to keep up their system of informers and spies.

To help monitor the situation and assist in gathering information, about 30 men from the South African Special Forces (colloquially known as the Recces) and several South African Military Intelligence operators were placed in SWAPOL. As part of the Recce contingent, several Swahili-speaking operators were also included to monitor the Kenyan soldiers of UNTAG. This military operation was known as Operation Saga. The deployed Special Forces contingent would only use the Police as cover and still send their information directly to the Senior Operational Special Forces Officer in Windhoek.

The man: Hermann Carstens

Hermann as band major, Hoërskool Voortrekkerhoogte

Hermann Carstens was born on 30 September 1968. He was the son of a South African military officer and went to Laerskool Uniefees (English: Uniefees Primary School), 25 km north of Pretoria. He later attended Voortrekkerhoogte Hoërskool (English: Voortrekkerhoogte High School), which mainly comprised children of military personnel.

It was in this environment that the young Carstens soon proved himself as a man destined for a bright military career. Among other, he was the band major of the school’s military band; as an athlete, he excelled in field and track events, and was a very good long jumper.

After completing his school career in 1986, he joined the South African Defence Force (SADF), like all young white men of that age. But he would not remain an ordinary soldier. He had a vision. He was driven. He wanted to be with the best. He volunteered for selection to the elite South African Parachute Battalion and passed the course. But even that was not good enough, and when the Recces visited, he volunteered again.

This time he was among the big fish. Special Forces all over the world usually comprise older soldiers; not 18- or 19-year-olds. But he was one of the exceptions. Hermann passed the selection, continued with the course and passed the course. He was not even 20 years old.

When the teams from the reconnaissance regiments were selected for Operation Saga, it was decided that all of them would first complete an advanced medical course, as this would be their cover: They would be medical personnel. Hermann was too late, however, and did not partake in the medical course. He was later sent to join those who had already been selected for the operation. This was fate – and he would be destined to be behind the exposed guns of a Casspir on 4 April 1989. The other Recce in the ambush that day was inside another Casspir – as the operational medical orderly (“ops medic”).

Hermann during Recce training

Operation Saga: Corporal Hermann Carstens

Operation Saga, an independent Special Forces operation, was planned as a long-term intelligence-gathering operation in northern SWA. This operation and other combined operations were aimed at painting a real-time intelligence picture of events that were unfolding as UNTAG and the SWAPO exiles started arriving. Their cover was also changed from medical personnel to members of the SWAPOL Security Police, as this would ensure more freedom of movement without raising suspicion.

At the start of February 1989, the operators from the Special Forces contingent arrived in Oshakati after spending a week preparing at the SWAPOL Security Police farm on the outskirts of Windhoek. They used the cover of the Security Police and also received police ranks. Another few days of preparation followed in Oshakati at the Security Police Headquarters before they were deployed. The 4 Reconnaissance (“Recce”) Regiment (4RR) was deployed to the Kavango and Caprivi regions, while the 1 “Recce” Regiment (1RR), supported by some operators and intelligence personnel from 5 “Recce” Regiment (5RR), was deployed in the central and eastern areas. The 1RR and 5RR area of operations stretched from Nkongo in eastern Ovamboland and west to Opuwa in the Kaokoland. The operators were posted at Security Police bases. Constables (Corporals) Pieter du Plessis and Hermann Carstens were deployed to the Security Police base at Okatope in Ovamboland.

Throughout March, in terms of the agreed-upon UN Resolution 435, UNTAG soldiers arrived in dribs and drabs to become the interim authority on 1 April 1989.

On Friday 31 March 1989, Koevoet (the SWAPOL Counter-Insurgency Unit, or SWAPOL TIN) and SWAPOL Security Police patrols were placed on high alert along the border in anticipation of a possible SWAPO invasion. Earlier, police informers had brought information regarding the execution of a SWAPO invasion plan on 31 March 1989.

On the Saturday morning of 1 April 1989 events took a turn for the worse as heavily-armed SWAPO insurgents began to invade SWA. The police were under pressure as heavy fighting broke out. Koevoet bore the brunt, as all the South African Defence Force (SADF) units had either been disbanded or were confined to base.

For the time, before the army could be mobilised, SWAPOL used everyone at its disposal. Security Police teams also deployed on 1 April 1989. Over the next four days, the bloodiest fighting of the war took place on SWA soil. The SWAPO groups were large, with up to 250 insurgents in a group. As the groups were attacked, they scattered and splintered off into smaller units.

On 4 April 1989 near Eenhana, Call Sign 21C – the Okatope Security Police team of which Pieter and Hermann were members – left their temporary base near the SADF’s Okankolo base just after 08:00 to patrol the area. Because he had not been on the advanced medic course, Hermann was appointed as one of the vehicle commanders, which entailed manning the mounted machine guns. Pieter, in the absence of the team medic who was on leave, acted as the Ops Medic in the other Casspir.

At approximately 11:45 four sets of tracks, about three hours old, were discovered. After following the tracks for a while, they noticed that more SWAPOs had joined, bringing the total number to more than 10.

Hermann in the Operational Area, Northern Namibia 1988

The Security Police team entered a belt of thick vegetation, followed by grassland and then a mahango field and a kraal. About 3 km south of Eenhana, SWAPO initiated an ambush with AK-74 and RPG7 rocket grenade launchers. At this stage, Hermann’s Casspir was ahead of the rest of the team, busy with voorsny[English: tracking ahead]. Voorsnyis a term used when some of the vehicles drive ahead to see whether they can perhaps pick up the tracks further ahead. When they can identify indeed tracks further ahead, the rest of the team is informed per radio to also come to the newer tracks. This means that a part of the tracking can be avoided, and the insurgents be caught up with quicker.

It was during this voorsny that Hermann’s Casspir entered the ambush. Standing up, he shot back with the twin Three Os Brownings from the machine gun turret at an angle behind the driver. It was possibly just after the start of the ambush that an insurgent fired a projectile at the Casspir with a RPG7 rocket grenade launcher. The projectile entered the Casspir on the left, about 800 mm above the gear box, in line with the firing holes below the front side window of the passenger compartment. The red-hot metal shrapnel caused devastation inside and hit Hermann from behind where he was firing the guns. His back was littered with shrapnel. A large piece of shrapnel hit him in the back of his head, and he died instantly.

The rest of the team fought through the ambush and started to maal[English: to mill]. This is a tactical move used and perfected by Koevoet, and was also used by the SWAPOL Security Teams and 101 Battalion. It entails all the vehicles fighting through the ambush and thereafter driving in different directions through the contact area to confuse the enemy, thus presenting a difficult target and engaging the enemy from every direction. Sometimes it even happened that the insurgents were overrun and killed with the Casspir’s wheels.

Pieter still remembers when his Casspir drove past Hermann’s Casspir; he saw Hermann slumped forward in the machine gun turret. The right rear wheel of Hermann’s Casspir had been shot out and the vehicle came to a standstill. In the ensuing contact 12 SWAPO’s were killed (one perished under a Casspir’s wheels during the maal, while two blew themselves up). More than 20 insurgents were part of the ambush.

About three minutes later when the contact had died down, Pieter made his way over to Hermann, and saw he had a wound behind his ear; all his vital signs indicated that he was dead. Hermann’s body and a wounded yet walking Special Constable Matheus Gabriel was casevaced by helicopter. Gabriel had shrapnel in his throat. A Koevoet team arrived, reported (and by doing so effectively claimed) the deaths and followed the tracks of the remaining SWAPOs who had escaped and later that afternoon killed another seven of them.

The legacy: The last man to die

It took nine days to stop the treacherous SWAPO incursion. When the last shot was fired, more than 300 of the estimated 1 500 insurgents had been killed. Between the SADF, which had since been released from their bases, and the initially under-gunned and under-strength police force, 31 people from the Security Forces died. Lt. Els of the Special Service Battalion was wounded on 3 April. He died of his wounds on 4 April. Several SWAPOL and South African Counter-Insurgency policemen would also be killed in action on 4 April 1989; however, the last soldier to be killed in action was the brave Corporal Hermann Carstens. He was, like most South Africans who had died in that war, a very young 19 or 20 years old. But this young man was destined to be there. As a young man he set high standards, and against all odds became the Recce he wanted to be. Hermann Carstens was a man who pursued his dream, and then started to live it.

After his death, Hermann’s fellow operators sent his boots, covered in gold, back to his parents.One of the boots is now in Duxford, England, with Renier Jansen, his close friend from high school. The bond between the two young men always remained. The other boot is with Hermann’s father in Pretoria

Hermann was buried with full military honours in April 1989, in the Heroes Acre at the Warmbad Cemetery. The town is now known as Bela-Bela. His bravery will be remembered forever by a special stone on his grave.

On 23 June 1974, Lt. Fred Zeelie became the first South African soldier to die in action in the Namibian Border War. He was from 1RR. On 4 April 1989, Corporal Hermann Carstens of 1RR became the last South African soldier to die in action during the Border War. Between the deaths of Fred Zeelie and Hermann Carstens, 61 more members of the South African Special Forces made the ultimate sacrifice. The contribution of the South African Special Forces in this war, and the cost in lives that they paid, is significantly higher than the average casualties of any other unit.

Freddie Zeelie (left) and Hermann Carstens (right)

Hermann Carstens will be remembered during the 13thAfriforum Springbok Vasbyt 10 & 25 km Road Race in 2019, and his name will be given a special place among the previously-unknown soldiers honoured by this event.

Published with the kind permission of Tinus de Klerk and Leon Bezuidenhout

Copyright: Tinus de Klerk & Leon Bezuidenhout

THIS ARTICLE IS NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE, OR TO BE SOLD IN ANY FORM Renier Jansen reserves the copyright of all photos

Introduction and Edited by Peter Dickens