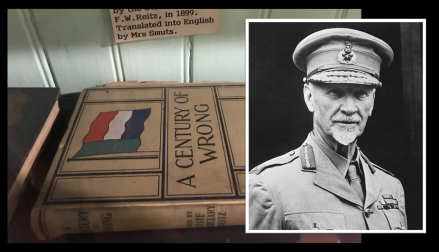

A friend of mine, Dennis Morton is a prolific researcher and he brought up this rather interesting history which highlights the rebellious nature and political dichotomy in white South African families perfectly. So, here’s how a Boer war rebel’s history massively impacted South Africa’s liberal political landscape.

The Irish Brigade

During the South African War 1899-1902 (the Boer War), a number of British, especially Irish found themselves in alignment with the Boer Republic cause. Many of them were working on mines in the Transvaal or had otherwise settled and repatriated in the two Boer Republics prior to hostilities. Not just Irish, these ‘burgers’ also constituted many other Britons – Scots and even the odd Englishman. At the onset of the war they volunteered to join a Boer ‘Kommando’, and this one was special, it was created by John MacBride and initially commanded by an American West Point officer – Colonel John Blake. The Commando was called ‘The Irish Brigade’ mainly because of its very Irish/Irish American slant. After Colonel Blake was wounded in action at the Battle of Modderspruit, shot in the arm, command of the Irish Brigade was handed to John MacBride. The Brigade then saw action in the siege of Ladysmith, however this was not a happy time for Irish Brigade as its members were not enthusiastic about siege tactics. After the Boer forces were beaten back from the Ladysmith by the British the Irish Brigade began to fall apart. It was resurrected again as a second Commando in Johannesburg under an Australian named Arthur Lynch and disbanded after the Battle of Bergendal.

To say the Irish Brigade was controversial is an understatement, the whole of Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom in 1899 (the Irish Republic split came much later) and members of this Brigade ran the risk of high treason if caught, especially if their ‘citizenships’ to the Boer Republics were not in order when the war began, or if they joined and swore allegiance to the Boers during the war itself.

So, at the end of the war there are a couple of Irish Brigade Prisoners of War who were captured and sent to St. Helena (which was the main camp for Boer POW) and they needed to be repatriated, in their case – the United Kingdom. The issue of treason hangs heavily on both of them.

Firstly, Prisoner 3783, Thomas Enright, an Irishman, who at one time was in the British army during the Matabele War and had changed allegiance to the Boer Republics, joining the Irish Brigade. The issue been the date of his burger citizenship which exceeded the amnesty for who was and who was not considered a ‘Burger’. The cut off for amnesty on oaths of allegiance by ‘foreigners’ to the Boer Republics was given as 29th September 1899.

The second is Prisoner 15910, John Hodgson, a Scotsman born at Paisley in the United Kingdom, he emigrated to Southern Africa in 1891. He lived in Rhodesia and moved to the Orange River Colony until 1896. He took the oath of allegiance to the South African Republic – ZAR (Transvaal) on the 28th or 29th December 1899, which was after the amnesty date. He served in the Irish Brigade under Blake and was captured by the British on 19th November 1900.

Luckily for both these men, they are not prosecuted for treason (which carried the death sentence) and repatriated to the United Kingdom after some heady politicking. Here’s where we stop with Thomas Enright and follow the Scotsman, John Hodgson.

On John Hodgson’s repatriation he is immediately ostracised by the British community because of his role on the side of the Boer Republics and six months after his return to the United Kingdom, he illegally boarded a ship bound for Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Here he set up shop working as a book-keeper and by 1904 John Hodgson’s family reunited with him in the Cape. Now, here’s the interesting bit that so often plagues ‘white’ South African families, although John Hodgson joined the Boer forces as a rebel, he, like many other Boer veterans, also harboured liberal political beliefs. He supported legal equality and the extension of a non-racial franchise (vote to all – Black emancipation) in Southern Africa.

Liberalism in South Africa

John Hodgson’s daughter, did not fall far from the tree, John’s rebellious and highly liberal nature rubbed off on her, she was Violet Margaret Livingstone Hodgson, who later married another liberal, William Ballinger. Margarat Ballinger would go down as a powerhouse in liberal politics in South Africa.

Margarat Ballinger would become the first President of The South African Liberal Party when it formed in 1953 and she would serve from 1937 as a Member of Parliament alongside Jan Smuts and his heir apparent Jan Hofmeyr. Highly vocal, she represented the Eastern Cape on the ‘Native Representatives Council’.

By 1947 her plans included new training and municipal representation for South African blacks and improved consultation with the Native Representatives Council. Time Magazine called her the ‘Queen of the Blacks’. Time Magazine went on to say Ballinger was the “white hope” leading 24,000,000 blacks as part of an expanded British influence in Southern Africa. Her Parliamentary career would take a dramatic turn when the National Party came to power in 1948.

By 1953, the ‘liberal’ side of the United Party lay in tatters, both Jan Smuts and Jan Hofmeyr had passed away in the short years of the ‘Pure’ National Party’s first tenure in power between 1948 and 1953. The Progressive Party and Liberal Party of South Africa would take shape to fill the void left by Smuts and Hofmeyr. The Liberal Party of South Africa was founded by Alan Paton and other ‘liberal’ United Party dissidents. Alan Paton came in as a Vice President and Margarat Ballinger the party’s first President. Unlike the United Party, the Liberal Party did not mince its position on the ‘black question’ and stood for full ‘Black, Coloured and Indian’ political emancipation and opened its doors to all races, they stood on the complete opposite extreme to the National Government and Apartheid and to the ‘left’ of the United Party.

Margarat Ballinger strongly voiced her anti-Apartheid views, opened up three ‘Black’ schools in Soweto without ‘permission’ and was one of a vocal few white voices openly defying H.F. Verwoerd. In 1960 she left Parliament when the South African government abolished the Parliamentary seats representing Black South Africans.

The Apartheid government’s heavy clampdown on ‘white liberals’ after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 forced many Liberal Party members into exile and many others were subject to various ‘banning’ actions locally. By 1968 the Apartheid government made it illegal for members of different races to join a singular political party, and instead of abiding the legislation (which the Progressive Party and others did), the Liberal Party stood it’s ground and chose to disband rather than reject its black members.

Not without a passing shot, in 1960 Margarat Ballinger published a scathing critique of Apartheid in a book she wrote called “From Union to Apartheid – A Trek to Isolation”. Ironic considering her family’s journey as a supporter of the ‘Boer’ cause. Regarded today as a ‘must read’ for anyone studying this period of South African history and Liberalism. She also wrote a trilogy on Britain in South Africa, Bechuanaland and Basutoland. Margarat passed away in 1980, before she could see the end of Apartheid.

In Conclusion

So, there you have it, an unusual and very South African family story, a strong minded Brit turned Boer rebel and his equally strong minded daughter, one who would become a pioneer of woman and liberalism in South Africa. It also reminds us as to the complexities and paradoxes of The South African War 1899-1902 and the different political sentiments at play within the Boer Forces, some of which can still surprise many today.

Written by Peter Dickens with great thanks to Dennis Morton for his research and writings.