South Africa’s worst military defeat – The Fall of Tobruk

The featured photograph of Field Marshal Rommel inspecting South African and British Prisoners of War (POW’s) after the fall of Tobruk is very telling of South Africa’s singular biggest capitulation of arms in its proud military history. Sir Winston Churchill, who rather embarrassingly on his trip to Washington had to hear the news from President Roosevelt, was to famously later write on his feelings about the fall of Tobruk:

“This was one of the heaviest blows I can recall during the war. Not only were the military effects grim, but it affected the reputation of British arms ……. Defeat is one thing; disgrace is another.”

So let’s have a look at why this loss of a small North African coastal port in World War 2 affected the British in this way, its ramifications for the British and South Africans, and why Churchill chose such a harsh rebuke of South African military prowess – which prior to Tobruk had been held in high regard and after Tobruk the South African military establishment literally had to fight an uphill battle in Italy to earn their respect again and recover their honour. In effect we need to ask ourselves if this was indeed a fair comment, so let’s have a look at what actually happened.

The Rats of Tobruk

The Rats of Tobruk was a nickname given to the soldiers who held the small Libyan port of Tobruk against Rommel’s German ‘Afrika Corps”and their Italian axis forces. Rommel had laid siege to the port in his push to invade Egypt, these hardened, belligerent soldiers effectively put Rommel’s plans on hold as they dogmatically dug in and resisted for 8 long months. The siege started on 10 April 1941 and was only to end later in November 1941.

They consisted of around 14,000 Australian soldiers from the 9th Australian Division commanded by Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead, accompanied by regiments of British artillery, the Polish Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade and 3rd Indian Motor Brigade – reporting to Australian command. In all they constituted about 30 000 troops – a very strong garrison.

At the time the port was surrounded by a strong line of defences, the garrison had air support, and Rommel had been at the end of his supply lines. Early Axis attacks were disorganised affairs that were easily fought off, and by the time Rommel was able to launch a stronger assault the defenders were really dug in ready to meet him. The defence of Tobruk became one of the iconic moments of the entire British war effort.

It dominated strategy in the desert in 1941, and the relief of Tobruk was the target of the unsuccessful Operation Brevity and Operation Battleaxe. The siege was finally lifted as a result of Operation Crusader and in the aftermath Rommel was forced to retreat west out of Cyrenaica, ending the year back at his starting point.

Tobruk was held in hero status and its defenders, the ‘rats’ went into the annuals of history as legends.

South African Honour to defend Tobruk

Tobruk secured, the Australians finally relieved and cycled out, by 1942 the Allied Middle East Command decided to leave a ‘temporary’ force to hold Tobruk while a new strike force was built up near the new frontier – on the Gazala line to the west.

The ‘honour’ of defending Tobruk was given to the South Africans. The new garrison was to be formed by the 2nd South African Infantry Division with Major General Hendrik Balzazar Klopper in command. General H.B. Klopper, was a school teacher before joining the South African Army. He was a Major General of one month’s standing when he was given overall command of Tobruk with limited combat experience. In all the same number of troops, over 30 000 were given to him to defend Tobruk if attacked, as had been the troop strength with the Australians earlier. Only with some relatively small but key differences.

Simply put, the defences of Tobruk weren’t as solid in 1942 as they had been in 1941. The main reason for this was that large numbers of mines had been lifted and moved to the Gazala line, as had a great deal of the barbed wire. The tank traps and anti-tank ditch were also in a very poor state and had begun to silt up with sand. Although not ideal, this condition of the defences left to Klopper was highlighted as the cause of the defeat in the subsequent military tribunal held after the war – and it effectively exonerated him of the defeat – however modern historians are now pointing to the fact that General Klopper had more than enough resources at his disposal to mount a convincing defence.

These historians point out his plus side, and its impressive, General Klopper had at his disposal some fine fighting units and very good equipment, he had his own division, the second South African Infantry Division, as well as some British and Commonwealth detachments – 60 Infantry Tanks of the 32nd Army Tank Brigade, the 201st Guards Brigade, the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade, three regiments of field artillery and two of medium artillery. There were 35 000 men in total. Tobruk had also now become a major supply base for the Gazala Line, and as a result was also crammed full of stores, ammunition and equipment.

But, again on the down side, unlike the Australians, there was little chance of solid air support for the South Africans, as the Desert Air Force had been forced to retreat to Sidi Barrani, and there were only fifteen 6-pounder anti-tank guns in the fortress.

There was also another very important difference, this time some of the defending troops were exhausted, their morale was lower, and the garrison was filled with a feeling of insecurity and impermanence. Something later historians would point it out as a failing as General Klopper had not inspired change or adequately dealt with it, other sources point to the relative inexperience of the South African troops, stating that although morale amoungst the South Africans specifically has high, their Commander himself was out of his depth.

That all said, what’s the big deal surrounding this tiny Libyan port – why’s was it so important to the North African Desert campaign? The answer is simply because it was the only deep water harbour in the theatre of operations – critical for supply and shipping of fuel, equipment and munitions to either the Axis forces or the Allied forces. To this end Tobruk was a key strategic asset – and all the Allied commanders knew it.

The fatal flaw

In terms of the defence perimeter, the Western and Southern sides of the port were well defended by the South Africans, but the East side was weak, and it proved to be fatal.

The eastern perimeter defences were left in a very weak state, and now they were to be defended by mainly Indian regiments reporting to General Kloppers command located in the centre. The 2/5th Mahrattas and the 2/7th Gurkas were great fighting units and till that point had been involved in the thick of fighting, so they had been pulled to rear to recuperate and these men were utterly exhausted.

An even more critical flaw in planning was an underestimate of German resolve, by both the Allied command and General Klopper. Erwin Rommel’s was utterly resolved to take Tobruk once and for all, his entire campaign to invade Egypt depended on it, and unlike the earlier siege of Tobruk with its Australian defenders, now he was going to throw just about everything at his disposal into the advance on Tobruk. He replenished and reinvigorated his forces, consolidated his plans and began his advance east again.

The Desert Fox Attacks

General Erwin Rommel had a fearsome reputation amongst the Allied Forces and was nicknamed ‘The Desert Fox’ by his enemy because of his skill in manoeuvre and deception, as usual for Rommel he also devised a ruse for capturing Tobruk.

Only his infantry approached the western perimeter, while his mobile forces swept on past, to give the impression that the German and Italian armour was heading straight for the Egyptian border (sending radio messages to that effect to complete the ruse). He then swung his mobile armoured forces around and attacked Tobruk from its weak point – the eastern perimeter.

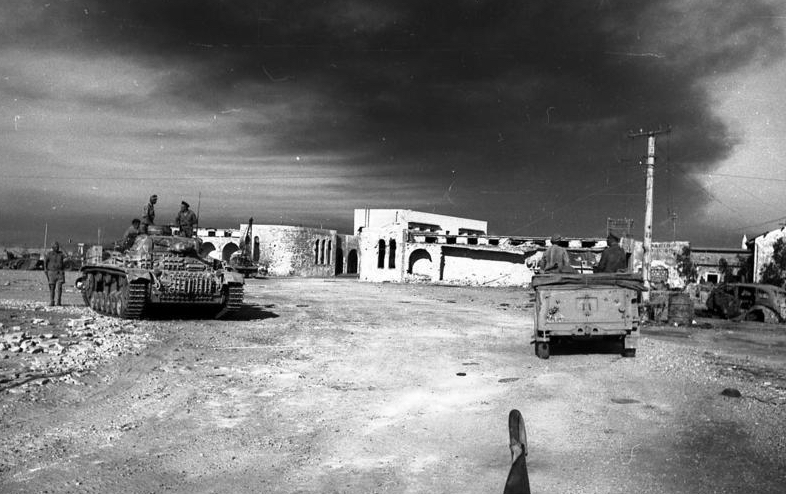

Rommel’s zero hour was 05h20 on 20 June 1942. As dawn broke long black lines of tanks, trucks and infantry slowly started to move forward. As it grew louder and closer to Tobruk waves of German Stukas and Ju 88’s aircraft appeared overhead (Rommel pressed every single Axis airplane in service in North Africa into taking Tobruk).

As the heavy artillery began to fire, the planes released their bombs and quickly got out of the way for the next wave, operating a shuttle service between the defence perimeter and El Adem airfield, 10 miles away. They pounded a gap open 600 yards wide. Behind them, under cover of artillery barrage and half-hidden by smoke and dust, German and Italian sappers raced forward to lift mines and bridge the tank traps with tanks and infantry racing through the gaps. As they move forward, they lit green, red and purple flares and the Stukas dropped their bombs just ahead of the advancing, multi-coloured smoke screen while the other planes and artillery blasted the South African rear (the seaward side of the port) with shells and bombs.

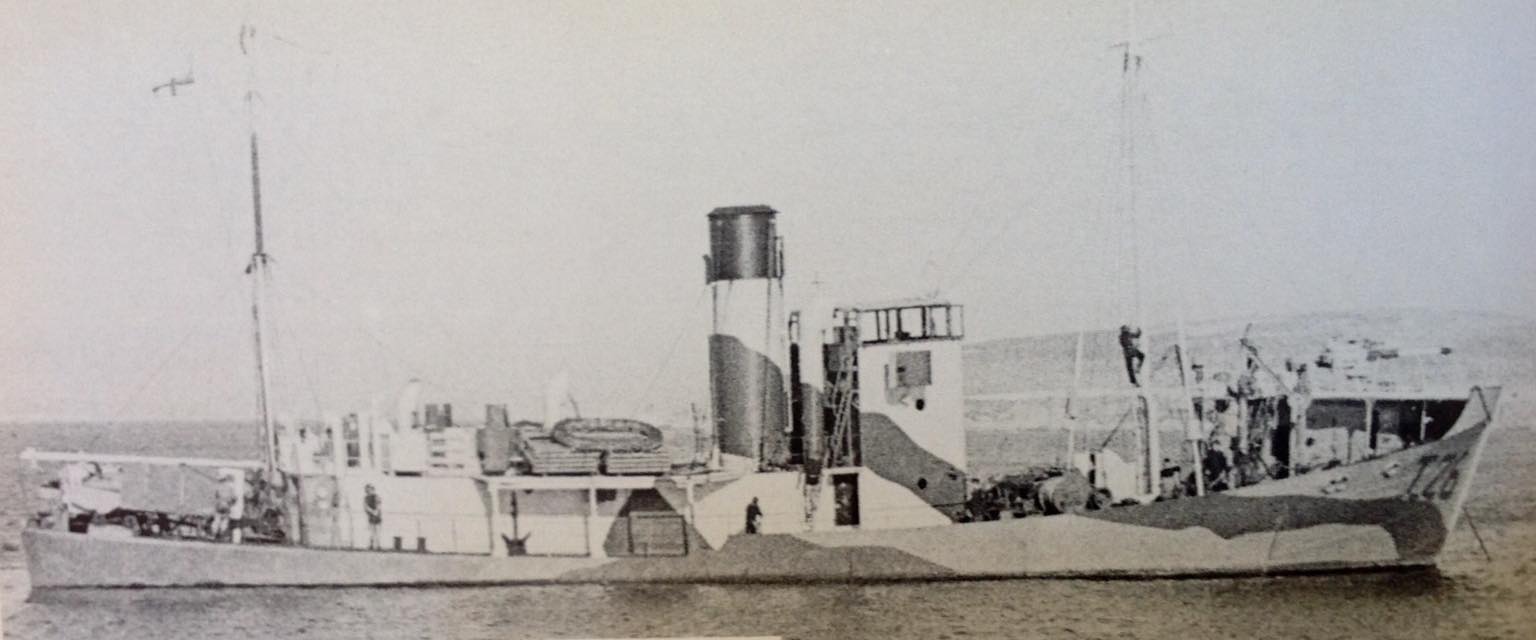

The situation inside Tobruk under this juggernaut attack very quickly became very desperate. It literally became a fight for survival and into the fight went everyone, including the ‘non combative’ members of The South African Native Military Corps who were given rifles and expected to fight on the front line with everyone else. As the fight became more and more desperate, three small minesweepers, two of them South African – the HMSAS Bever and HMSAS Parktown were called into port to take on evacuation duties.

Both the Bever and the Parktown acquitted themselves in the highest order whilst under a hail of shelling and bombing – and please feel free to refer to two earlier Observation Posts’ links for an in-depth profile on their brave fight – “Under a hail of shells”; Recounting the bravery and loss of HMSAS Bever and The feisty South African minesweeper that went down fighting – HMSAS Parktown

Inside Tobruk the situation was chaotic. General Klopper – his Head Quarters now bombed out, his radio and telephone wrecked and his code booked destroyed, lost the last vestige of control.

Left with no choice General Klopper and staff could do nothing but watch the German Panzers (tanks) race past their headquarters on their way to capture the fuel dumps in the harbour.

Some British and South African troops managed to break out and make their way back to Allied lines, whilst most stayed and fought a lost cause as grimly and with as much determination as they could. By dawn on 21 June 1942, Tobruk was just a pile of ruins with a massive pall of smoke reaching up into the atmosphere. The harbour riddled with the wrecks of destroyed ships. General Klopper gave his compass and staff car to 7 young South African soldiers determined to escape, saying, ”I wish I was coming with you.”

Surrender and shame

Shortly afterwards a small party of officers set off in a truck with a little white flag of surrender fluttering over the hood to negotiate terms of surrender, and by 09h40 Tobruk was officially turned over to Rommel. Soon after, a large white flag was hoisted over the South African Head Quarters by South African Native Military Corps drivers.

And that was it. Major-General KIopper formally surrendered with 32,000 men, including 10,722 South Africans of the 2nd Infantry Division, of whom 1,200 were members of the Native Military Corps, and all the British and Commonwealth units under his command. Of the two South African Infantry Divisions in the North African combat zone of operations, one entire division (literally half of the South African Army’s fighting force in North Africa) went into captivity. This and thousands of tonnes of resources – the Germans captured 2,000 tons of fuel, 5,000 tons of provisions, 2,000 vehicles and large stockpiles of ammunition – the situation now for the Allies in North Africa was a very grim one indeed.

Britain’s entire war effort was now compromised and very much in the balance, the fight from here out would be a herculean one. It was also the single biggest capitulation of South African forces in the country’s history – before or since. Now you can begin to see Churchill’s point, as to him it seemed more than a ‘defeat’ and more of a ‘disgrace’ – as in the Battle of Britain in 1940, without this vital deep water port, the British and Allied armed forces by 1942 found themselves once again with their backs against a wall – and as a result South Africa was going to get the full blame for it by literally every single Commonwealth country, Allied country and the British themselves.

Captivity

The South African, British and other Commonwealth units forced to march across the desert to an Italian POW camp. The Italian treatment of South African and British prisoners of war was nothing short of diabolical, prisoners were murdered, punitive measures on food allocations and other atrocities became normative.

However an even worse treatment was reserved for Black members of the South African Native Military Corps and the Indian troops in captivity. German and Italian forces displayed a complete disregard for the rights of the Indian or black POWs as they did not view them as regular troops due to Nazi and Facist doctrine and in-bred racism .

There are however accounts of bravery whilst in captivity, with a number of escape attempts and escapes. Even that General Klopper himself managed to escape captivity in 1943.

One notable heroic deed in captivity at Tobruk was that of a South African Native Military Corps man – Job Maseko, who created a bomb using a condensed milk tin, cordite taken from bullets and an extremely long fuse to blow up a German freighter ship (F Type) in Tobruk harbour as a retaliation for his treatment as a black man and those of his colleagues by the Italians. To learn more of his heroic tale please visit this Observation Post link Job Maseko; one very remarkable South African war hero

Rommel’s Success

After 2 years in British hands Tobruk had fallen in 2 days, Rommel had captured enough supplies to carry him on his drive to invade Egypt. On 22 June 1942, Rommel received a message from the Fuhrer – Adolph Hitler, informing him that at the age 49 he had just been appointed Germany’s youngest Field Marshal.

Rommel celebrated that night with canned pineapple and a small glass of whisky, but after dinner he wrote his wife, ”Hitler has made me a Field Marshal. I would much rather he had given me one more division.”

But true to character, by the very next day he was on the advance again. His order: ”Soldiers of the Panzer Army Africa! Now we must utterly destroy the enemy! During the coming days I shall be making great demands upon you once more, so that we may reach our goal.” The Nile.

Rommel would never get to the Nile and take Egypt. For Winston Churchill the German advance in North Africa was the desperately needed ‘second front’ which would see the end of Nazi Germany, for the Germans however the North African campaign was nothing more than a side-show in support of Italian imperialism in Africa. The bulk of their military effort was focussed on the invasion of Soviet Russia. Hitler discontinued the attack on Malta and refused to send Rommel adequate supplies, these actions would make defeat in the North African desert for Germany and Italy inevitable.

Consequences for the British and South Africans

Ironically there was an upside to the Fall of Tobruk, The defeat did have some positives. It forced Churchill and the British to fundamentally re-appraise the Command and strategy in North Africa. It led to a shake up of Command which would see General Bernard Montgomery take over overall Command of the British 8th Army (after Churchill’s original replacement, General William Gott was killed in action). Under ‘Monty’ the entire operation received a boost in resources, purpose and training (including much-needed American armour). Monty and the 8th Army would then go on to victory at El Alamein and more successive victories for the British and Commonwealth forces followed (eventually with American assistance when they entered the war), and it would see the entire German Afrika Corps pushed back completely from North Africa and into captivity. The issue of Tobruk and Britain ‘against the wall’ gradually became a distant memory.

The remaining South African forces in North Africa i.e, The 1st South African Infantry Division would go on to recover their reputation somewhat in these strings of success under Montgomery, also starting with Battle of El Alamein. However Tobruk continued to haunt them and the British still remained dubious of South Africa’s military prowess by the time the next phase i.e. the Italian campaign came around.

After the 1st South African Infantry Division’s job was done in North Africa, the 6th South African Armoured Division was formed to continue with South Africa’s World War 2 contribution. The British initially wanted to side-line the 6th South African Armoured Division and allocated it just to go to Palestine – in what was really a side-show.

At this point it is actually Churchill who comes around to bat for the South Africans, despite his anger and lambasting of the South Africa military establishment as a ‘disgrace’ over Tobruk, it is Churchill (influenced by Jan Smuts) who insisted that the South African 6th Armoured Division join the main thrust of the war in Italy and not sit it out in Palestine. The 6th South African Armoured Division then went on to serve in Italy with great gallantry and distinction – and ultimately recovered the country’s pride.

General Klopper’s career post Tobruk

The fall of Tobruk came as a shattering blow to the British public and British morale. General Klopper came in for most of the criticism, but was he entirely to blame? The inquest into the Fall of Tobruk found fundamental short-falls in overall British Command and the decision to invest in Tobruk and concluded that General Klopper was placed in an extremely difficult position at Tobruk from which he had little hope of a proper defence – the circumstances he had faced were very different to those the Australians had faced before. In conclusion to the inquest General Klopper was exonerated for the loss of Tobruk.

General Klopper however did come into a hail of controversy as to his command ability and experience subsequently to the inquest, and had South Africa remained a British Dominion after the war it would have been doubtful that his career would have advanced.

Luckily for General Klopper, the Afrikaner Nationalist government came into power in 1948, and he found more favour with them than he did under the old Smuts government. The new Nationalist Minister of Defence, Frans Erasmus and his ‘Erasmus Reforms’ of Union Defence Force sought to advance ‘Afrikaner’ personnel above all else – and he saw to it that Klopper was very controversially promoted to serve on the Army Chief of Staff from 1951 to 1953. After that a stellar career ensued as he was promoted to Inspector-General from 1953 to 1956, and finally he took the most honoured position in the South African Defence force as Commandant-General, which is the head of the South African Defence Force, a post he held from 1956 to 1958.

In conclusion

To answer the question of whether Churchill’s comment that South Africa’s capitulation at Tobruk was the difference between ‘defeat’ and ‘disgrace’ it can honestly be said that Churchill’s comment is somewhat unfair, however given the circumstances and the timing it is understandable that he was enraged, the consequences were very bleak for the British War effort.

Churchill was equally vicious in his remarks as to his own forces when the British garrison at Singapore capitulated due to poor command earlier in February 1942 with an equal consequence in the Asian Pacific field of operations. On Singapore’s fall Churchill asserted that the British commander General Percival’s decision to surrender was “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

So we have to take Churchill and his comments in context of the man, his politics and the circumstances he found himself in. Also, in the end it is Churchill himself who plays a role in recovering South Africa’s pride by insisting the 6th Armoured Division take part in the Italy campaign – even placing British Household Division Guards under South African 6th Armoured Division command as their Infantry support. In the greater scheme of things South Africans can hold their heads very high in the role they played ridding the world of Nazism in what Smuts would call ‘the Great War for Liberty and man’s Freedom’ – Churchill’s need to alliterate one of his quotes aside.

Researched by Peter Dickens

References – Wikipedia, Extracts and references from. THE GREATEST MILITARY REVERSALOF SOUTH AFRICAN ARMS: THE FALL OFTOBRUK 1942, AN AVOIDABLE BLUNDER OR ANINEVITABLE DISASTER? by David Katz. Extracts from Military History Journal Vol 7 No 6 – December 1988 TOBRUK – 1942 Compiled and translated from the official War Diary of the German Supreme Command by Jochen OEO Mahncke. Image copyrights – Imperial War Museum. Narratives from North Africa: South African Prisoner of War experience following the fall of Tobruk, June 1942 by Karen Horn.

The brave men of the HMSAS Bever sacrificed that day are outlined on the honour roll below (MPK means “Missing Presumed Killed”):

The brave men of the HMSAS Bever sacrificed that day are outlined on the honour roll below (MPK means “Missing Presumed Killed”):

Back in the day, there was always a base rumour that the SADF put ‘Blue Stone’ into the food and drink to repress the sexual urges of young National Servicemen. It was always declared as proof positive by some or other young recruit whenever the coffee urn came out and the ‘strange salty taste’ was attributed to this drug.

Back in the day, there was always a base rumour that the SADF put ‘Blue Stone’ into the food and drink to repress the sexual urges of young National Servicemen. It was always declared as proof positive by some or other young recruit whenever the coffee urn came out and the ‘strange salty taste’ was attributed to this drug.

As to the myth of bromide, the comedian Spike Milligan, who served with the British Army in World War II, summed the myth up very well in his book Rommel? Gunner Who?

As to the myth of bromide, the comedian Spike Milligan, who served with the British Army in World War II, summed the myth up very well in his book Rommel? Gunner Who?

The Rand Rebellion (also known as the Rand Revolt or Second Rand Revolt – the Jameson Raid was the first) was an armed uprising of white miners on the Witwatersrand mining belt in March 1922.

The Rand Rebellion (also known as the Rand Revolt or Second Rand Revolt – the Jameson Raid was the first) was an armed uprising of white miners on the Witwatersrand mining belt in March 1922.

Gloucester was nicknamed The Fighting G and saw heavy service in the early years of World War II. The ship was deployed initially to the Indian Ocean and later South Africa before joining Vice Admiral Cunningham’s Mediterranean fleet in 1940. She was sunk on 22 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete with the loss of 722 men out of a crew of 807.

Gloucester was nicknamed The Fighting G and saw heavy service in the early years of World War II. The ship was deployed initially to the Indian Ocean and later South Africa before joining Vice Admiral Cunningham’s Mediterranean fleet in 1940. She was sunk on 22 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete with the loss of 722 men out of a crew of 807. After German paratroopers landed on Crete on 20 May, the cruiser HMS Gloucester was assigned to Force C that was tasked with interdicting any efforts to reinforce the German forces on the island. On 22 May, while in the Kythria Strait about 14 miles (12 nmi; 23 km) north of Crete, she was attacked by German “Stuka”s of StG 2 shortly before 14:00, together with the light cruiser HMS Fiji and the destroyer HMS Greyhound. The Greyhound was sunk and the two cruisers were each hit by 250-kilogramme bombs, but not seriously damaged. Two other destroyers were ordered to recover the survivors while the two cruisers covered the rescue efforts. Gloucester was attacked almost immediately and sustained three more hits and three near-misses and sank. Of the 807 men aboard at the time of her sinking, only 85 survived. Her sinking is considered to be one of Britain’s worst wartime naval disasters.

After German paratroopers landed on Crete on 20 May, the cruiser HMS Gloucester was assigned to Force C that was tasked with interdicting any efforts to reinforce the German forces on the island. On 22 May, while in the Kythria Strait about 14 miles (12 nmi; 23 km) north of Crete, she was attacked by German “Stuka”s of StG 2 shortly before 14:00, together with the light cruiser HMS Fiji and the destroyer HMS Greyhound. The Greyhound was sunk and the two cruisers were each hit by 250-kilogramme bombs, but not seriously damaged. Two other destroyers were ordered to recover the survivors while the two cruisers covered the rescue efforts. Gloucester was attacked almost immediately and sustained three more hits and three near-misses and sank. Of the 807 men aboard at the time of her sinking, only 85 survived. Her sinking is considered to be one of Britain’s worst wartime naval disasters.