Submariners are the true ‘heroes” of the Navy, known as the ‘silent service’ it is the most dangerous service any Navy can offer. The death of a submarine is a harrowing prospect to those who serve in it – it takes a very special and very brave person to serve in or command a submarine. Yet in South Africa we don’t really have any real idea of our bravest of the brave in the ‘silent service’ – we’re clueless and it’s because we “don’t know the half of it”.

Typically, in Navy circles, the South African Navy seems to begin regarding its ‘firsts’ from different political epochs and the confusion kicks in because the history of the South African Navy and the British Royal Navy in South Africa are so intrinsically muddled.

I recently came across a day to day in South African history by Chris Bennet, where he lists Lt. A. H. Maccoy DSC, serving on the Royal Navy’s submarine HM Umbra as the first South African to command a submarine.

With much respect to Chris Bennet, he does a cracking job keeping us abreast of our Naval history, but he is only partly correct. Lt. Maccoy DSC is the first member of the South African Naval Forces (formed at the beginning of World War 2) to be seconded to British Forces and command one of their submarines. BUT, and its a big but, he was not the first South African to command a submarine.

In fact, there is a long a rich heritage of South Africans who served on Royal Navy submarines who came before Lt Maccoy, and their service extends all the way back to the First World War. Not only these early South African naval pioneers, many of whom were sacrificed in the line of duty, there is even a bunch of very decorated and very heroic South Africans in command of British Submarines during World War 2 whose service pre-dates Lt MacCoy’s command.

So, who are all these South African submariners and why don’t we know anything about them in our contemporary account of South African military history?

The answer lies in the correct account of South African Naval history. After South Africa was formed as country in 1910 it did not have a navy as part of its armed forced. Naval protection and patrolling our shores was left entirely to the British and the Royal Navy. During WW1, all South African volunteers to join the navy found themselves in the Royal Navy from 1914.

It was only by the onset of World War 2 in 1940 that a South African Navy as we know it even started to take shape. Even in 1940, all the South African Navy could offer any South African volunteering to serve in Naval Forces were a handful of fishing trawlers converted to mine laying and mine hunting. The bulk of volunteers found themselves in the Royal Naval directly as Royal Navy Reservists or found themselves seconded to the Royal Navy as South African Navy personnel.

So lets have a look at the really ‘silent’ history of South African’s in the ‘silent service’ of submarines – and we start with World War 1.

Notable South Africans in submarine service – WW1

The First World War properly developed the submarine as a tool of war, it can even be argued that it is the beginning of the submarine service itself. It had been used in the American Civil War but it was only by WW1 that it became defined.

Even at this early time of submarine warfare we find some notable South Africans at the forefront of this foreboding weapon of war, here are their stories:

William Tatham

Sub-Lieutenant William Inglis Tatham, Royal Navy, was the Son of Lieutenant-Colonel The Hon. F. S. Tatham, D.S.O., and Ada Susan Tatham, of Parkside, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, the Tatham’s being a well-known Natal and South African family.

William Inglis Tatham

William Tatham was born in Natal and volunteered to join the Royal Navy to serve on submarines. He was assigned to H.M. Submarine “H3”, an “H” Class submarine was developed in 1915 to respond to German mine-laying ships, whose operations were taking a heavy toll on Allied Merchant shipping during the war – especially around the British Isles and the Adriatic.

H3 was built by the Canadian Vickers Company in Canada and it was commissioned on the 3 June 1915. H3, and her sister submarines H1, H2 and H4 sailed across the Atlantic and set up base in in Gibraltar.

One short month later, H3 was on operations in the Adriatic waters under the command of Lieutenant George Eric Jenkinson age 27, when she tragically sank on the 15 July 1916 after hitting a mine in the gulf of Cattaro while attempting to penetrate defences. H3 sinks with all 22 crew and unfortunately took our 19 year-old South African hero, Sub-Lieutenant Tatham with her. It gets worse for the Tatham family, William’s brother will be killed just 3 days later serving in the South African Infantry.

Royal Navy ‘H’ Class submarine from WW1

William Tatham enters our history books as the very first South African submariner to lose his life. He is not acknowledged as such or extensively remembered in South Africa by the government or South African Navy, he is however remembered in England, his and name appears on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

Charles Philip Voltelyn van der Byl

Lieutenant Charles Philip Voltelyn Van der Byl, Royal Navy, came from Cape Town, and like William Tatham he was also from an illustrious South African family. Charles van der Byl initially joined the Royal Navy and served aboard the battleship HMS Goliath, he is also a lucky survivor when the HMS Goliath was sunk during the Gallipoli campaign in the Dardanelles in 1915.

Lt. van der Byl then transferred to the submarine service and was assigned to HMS Submarine G1. G1 was a “G” Class submarine of the Royal Navy and was built at Chatham Dockyard, had a crew of 31 and a top speed of 14.5 knots (surface) and 10 knots (submerged). G1 was launched on the 14th August 1915.

Royal Navy G Class submarine from WW1

G1 would survive the war, however very sadly Lt Van der Byl would not, he was drowned on the 9 October 1916. His drowning having occurred just three months after the loss of his fellow South African pioneer and submariner – William Tatham,

Lt. Van der Byl’s name is also only really remembered in England, and is found on the Chatham Naval Memorial,

Wiggie Bennett

Another South African who served with the silent service during World War 1, was “Wiggie” Bennett, from Johannesburg.

Royal Navy ‘K’ class submarine in WW1

Wiggie was known as a fearless dare devil serving on K boat submarine patrols operating from Harwich, and again, rather tragically, he too paid the ultimate sacrifice.

Between the World Wars

As we pass between the First and Second World War’s we find another notable South African in the ‘silent service’ of the Royal Navy. Lieutenant Harold Chapman.

HMS Thunderbolt (Thetis)

Harold Chapman was a ‘Botha Boy’ having trained aboard South Arica’s notable training establishment – the South African Training Ship, General Botha. Chapman then relocated to the United Kingdom and entered the Royal Navy in 1927 as a Midshipman.

He entered the Royal Navy’s submarine service as second-in-command of HMS Thetis (N25) a T-Class submarine. Tragically the HMS Thetis sank during her sea trials on the 4 on the 1 June 1939, taking 99 men, including our South African submariner with her.

The tragedy was attributed to a test cock on the number 5 tube which was blocked by some enamel paint and no water flowed out the when the bow cap was opened, the inrush of water caused the bow of the submarine to sink to the seabed, 46 meters below.

The stricken Thetis, surrounded by rescue boats

Interestingly as the HMS Thetis was at a relatively shallow depth it was salvaged, brought back to operational service and became the HMS Thunderbolt, however HMS Thunderbolt was destined to be sunk again and was lost during WW2 off Cap St. Vito, north of Sicily, on the 14 March 1943, having been depth charged by the Italian corvette, “Cicogna”.

World War 2

By the beginning of the Second World War we find many more South Africans in the Royal Navy’s Submarine branch.

Voltelin James Howard Van der Byl

During the Second World War we find our first South African to command a submarine – Captain Voltelin James Howard Van der Byl, the second son of Lt.Col. Voltelin Albert William van der Byl, OBE (1872-1941), and Constance Margaret Jackson of Cape Town, South Africa.

Born in Cape Town on the 04 May 1907, Voltelin James Howard Van der Byl stemmed from famous Van der Zyl military family which attained political fame under Smuts in South Africa and ironically he was relative of Charles Van der Byl, mentioned previously who was sacrificed in a Royal Navy submarine during World War 1.

Voltelin James Howard Van der Byl joined the Royal Navy as a Cadet in 1924, attaining his commission as a Midshipman in 1925. Serving on various Royal Navy ships, he joined the submarine service in April 1929 and assigned to HMS Submarine Odin and serving in Chinese waters.

Promoted to First Lieutenant, he continued to serve on submarines and was assigned to HMS Sturgeon in 1933 in the China seas and HMS Rover in 1934. On the 8th August 1936, prior to the Second World War, he made history as the first South African to command a submarine, taking command of HMS Salmon serving in the Mediterranean.

HMS Salmon (N65) – WW2

At the on-set of World War 2, he was again assigned a command of submarine, taking command of HMS Taku (N38), the Taku was a British T Class submarine. On the 8 May 1940 Van der Byl found himself in the thick of combat, when he attacked a German convoy with ten torpedoes, damaging the German torpedo boat Möwe east of Denmark. For his actions he subsequently received the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) at the end of June 1940.

HMS Taku – WW2

By October 1940 he found himself as a Staff Officer to the Commander in Chief of the Home Fleet and in 1943 he served with the Anti-Submarine Warfare Division of the Admiralty (HMS President). By the end of the war in 1945 he found himself as the Commanding Officer, HMS Medway II (submarine base, 1st Submarine Flotilla, Malta).

Promoted to Captain, he remained in the Royal Navy after the war, retiring in January 1958 as the Commanding Officer of HMS Forth and as a Naval ADC to Queen Elizabeth II.

Captain V.J.H. Van der Byl, Royal Navy, DSC passed on in Hampshire, England on the 21st September 1968.

Frederick Basil Currie

Lieutenant-Commander Frederick Basil Currie of the Royal Navy, is another notable South African submariner of the Second World War. The son of Colonel O.J. Currie of the South African Medical Corps and Sarah Gough Currie. Frederick Currie was given command of HMS Regulus (N88) a R Class Submarine.

HMS Regulus (N88) – WW2

Frederick Currie was the second South African to be given command of a submarine and as is common to this very dangerous arm of service he was lost when the HMS Regulus went on patrol from Alexandria in Egypt, on the 23 November 1940. The general consensus is the HMS Regulus may have hit a mine just off Taranto, Italy, on the 6 December 1940.

Arthur Hezlet

Sir Arthur Richard Hezlet

A South African born submariner became one of the most famous submariners of the Second World War. His colourful career started in 1928 when Hezlet joined the Royal Navy aged just 13 years old. Nicknamed Baldy Hezlet he became the Royal Navy’s youngest captain at the time, aged 36 and its youngest admiral, aged 45. In retirement he became a military historian.

Born in Pretoria, South Africa on the 7th April 1914, he attended the Royal Navy Colleges in Dartmouth and Greenwich before going to sea in 1932 as a Midshipman on Battleships HMS Royal Oak and HMS Resolution.

Hezlet was promoted to Lieutenant on 1 April 1936, achieving the highest mark in his Lieutenant’s examinations and winning the Ronald Megaw Memorial Prize. In December 1935 he began the submarine course at HMS Dolphin, something for which he had “not applied or volunteered”. He however later volunteered to serve on submarines and ironically cut his teeth in 1937 on HMS Regulus (the same submarine on which fellow South African Frederick Currie later lost his life).

Following which he was appointed First Lieutenant of submarine HMS H43 from January 1938 to April 1939, and later transferred to the HMS Trident. On HMS Trident he was to see his first action when he was engaged in operations in the Norwegian Sea as the Germans launched their occupation of Norway.

He subsequently passed the notorious “Perisher” exam (Submarine Commanding Officers Qualifying Course), and thus became a submarine commander. He then commanded the following Royal Navy submarines during the war, HMS Unique, HMS Ursula, HMS Upholder, HMS Thrasher and HMS Trenchant.

His first combat test came when he was in Command of HMS Unique, when Hezlet fired four torpedoes at the Italian troop ship ‘Esperia – his first ever torpedo attack on the enemy and sank her. In November 1941 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his attack on the Esperia.

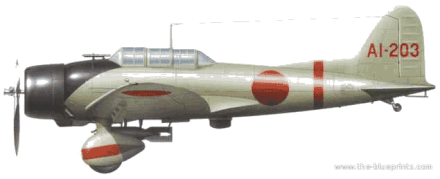

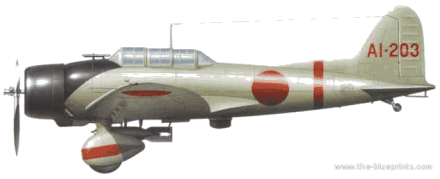

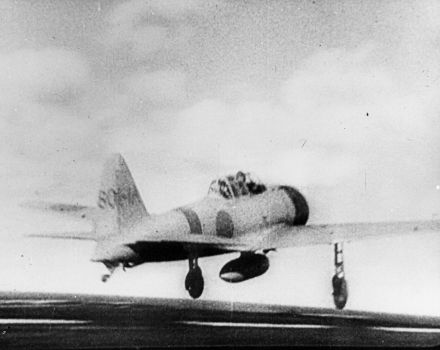

However, it was whilst serving as the Commander on HMS Trenchant that Hezlet became a submarine warfare legend. Taking Command on 15 October 1943, HMS Trenchant saw combat in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) during Operation Boomerang when she sank a Japanese coaster. Hezlet stopped to pick up survivors and managed to coax 14 Japanese crew to accept rescue.

HMS Trenchant during WW2

Hezlet undertook long-range patrols in the Indian and Pacific oceans, earning him his first Distinguished Service Order (DSO). when he sank the long-range German U-Boat 859 on 23 September 1944, near the Sunda Strait after receiving ‘Ultra’ decrypts on her position.

Under his command on 27 October 1944, HMS Trenchant deployed two MKII Chariot manned torpedoes ‘Tiny’ and ‘Slasher’ off Phuket on a mission to destroy two Axis merchant ships in what would prove to be one of the most successful uses of Chariots of the whole War.

Ironically, on one of the MKII Chariot manned torpedoes was another notable South African, Sub/Lt Anthony Eldridge DSC, he had joined the Royal Navy in January 1942 and was awarded the DSC for his outstanding courage and determination.

Sub/Lt Anthony Eldridge DSC

However it was the action on 8 June 1945 in which Arthur Hezlet walked into fame, Hezlet took HMS Trenchant into shallow and mined water in the Banka Strait to sink the Japanese heavy cruiser ‘Ashigara’, the cruiser’s protection, the Japanese Destroyer ‘Kamakazi’ spotted the Trenchant and attacked it. Despite being under attack, Hezlet held his nerve firing 8 torpedoes at the Ashigara, 5 of them struck and the Ashigara sank quickly. The Ashigara goes down in history as the largest Japanese warship sunk by a Royal Navy warship during the war

For his action on the Ashigara Hezlet was awarded a Bar to his DSO and the Americans awarded him the US Legion of Merit.

Japanese heavy cruiser ‘Ashigara’

After the war Arthur Hezlet would continue to have a stellar career in the Royal Navy’s submarine service and would later aspire to the rank of Vice-Admiral, and one of his subsequent appointments would be that of Flag Officer Submarines. In 1946 he was present at the nuclear test on the Bikini Atoll and would pioneer submarine nuclear capability in the Royal Navy. In 1964 he was appointed as Knight of the British Empire (KBE) and given the prefix of ‘Sir’. Sir Arthur Hezlet passed on aged 93 in 2007.

Peter Gibson

Lieutenant Peter Rawstorne Gibson, born in Umtata in the Transkei region of South Africa was lost with the submarine HMS Regent when it was lost with all hands on the 1 May 1943. Accounts to the loss of the HMS Regent differ, some accounts indicate it may have struck a mine after attacking the Italian tanker Bivona another theory is the Italian corvette Gabbiano depth charged her. In either event Lieutenant Peter Gibson and the crew of HMS Regent are ‘still on patrol’.

HMS Regent

John Claude Hudson Wood

John Claude Hudson Wood, born in Nyasaland (now Malawi) and educated at Durban High School, another ‘Botha Boy’ after high school he joined the Navy and completed his training aboard the South African Training Ship General Botha. He was lost whilst serving on submarine HMS Utmost on the 25th November 1943 when on patrol in the Mediterranean.

Crew of HMS Utmost with their “Jolly Roger” success flag

On the 23rd she sank an enemy ship, but on her return journey to Malta, she was located, attacked and sunk south west off Sicily by depth charges from the Italian torpedo boat.

X-Men

Some South Africans even found themselves in the most perilous of submarine service in the Royal Navy, the ‘X-Craft Midget Submarines.

Lieutenants’ P.H. Philip and J.Terry-Lloyd, both of South African Naval Forces (SANF) seconded to the Royal Navy’s submarine service, who gained fame for their role in “Operation Source” in September 1943.

X-Class midget submarine underway

Operation Source was a series of attacks to neutralise the heavy German warships – Tirpitz, Scharnhorst and Lützow based in Norway using X-Class midget submarines. The attacks took place in September 1943 at Kaa Fiord and succeeded in keeping Tirpitz out of action for at least six months.

Philip and Terry-Lloyd commanded X-Class midget submarines X7 and X5 respectively in the attack – for this darning mission both South African submariners were awarded MBE’s.

Lieutenant Alan Harold MacCoy

Lt A.H. Maccoy DSC

Now we finally get to Lieutenant Alan Harold Maccoy of the South African Naval Forces (SANF), seconded to the Royal Navy, who stands out in some historical accounts as the ‘first’ South African to command a submarine (albeit incorrect).

Lt Alan Maccoy served aboard the submarines HMS Sunfish (N81), HMS Pandora (42P), HMS Umbra (P35), HMS Porpoise (83M) and the HMS Tantalus (P98). He received his Distinguished Service Cross on the 25th May 1943 from King George VI at Buckingham Palace for his actions and service on the HMS Umbra.

Lt Maccoy was given command of British submarines towards the end of the war, when he commanded HMS Seaborne and HMS Unruffled (P46) having seen service nearly all theatres of maritime combat during the war. He was to serve out his service in his final command on HMS Unruffled until on the 18 Oct 1945 it was paid off into reserve at Lisahally.

The men of HMS Unruffled hoist the Jolly Roger

Post World Wars

The 70’s

Spool forward to the 1970’s – two significant moments stand out in the history of South Africans in the silent service, the handing back of Simonstown as a British Naval base to South Africa in a colourful ceremony on the 2nd April 1957, after being in British hands since 1813. A thorn in the Nationalist government’s agenda as Simonstown continued to operate as official British naval base after 1957 under the ‘Simonstown agreement’ and well after the Nationalist’s rise to power in 1948. The Simonstown Agreement terms finally ending when the United Kingdom government terminated the agreement on 16 June 1975 (citing in part – Apartheid).

Spool forward to the 1970’s – two significant moments stand out in the history of South Africans in the silent service, the handing back of Simonstown as a British Naval base to South Africa in a colourful ceremony on the 2nd April 1957, after being in British hands since 1813. A thorn in the Nationalist government’s agenda as Simonstown continued to operate as official British naval base after 1957 under the ‘Simonstown agreement’ and well after the Nationalist’s rise to power in 1948. The Simonstown Agreement terms finally ending when the United Kingdom government terminated the agreement on 16 June 1975 (citing in part – Apartheid).

In advance of this, South Africa saw the need to develop its own submarine program and began a covert operation in conjunction with the French in the late 1960’s called Operation Duiker to buy small French diesel powered shore patrol Daphne submarines.

On completion of trials the SAS Maria van Riebeeck (named after Jan van Riebeeck’s wife) was formally commissioned by Commander JAC Weideman on 24 July 1970 and accepted into the South African Navy as the first South African submarine. In 1971, two other Daphne class submarines were added, the SAS Emily Hobhouse and the SAS Johanna van der Merwe.

In the French tradition of giving submarines female names the focus was on South African woman who mattered to the Afrikaner Nationalist (NP) history of South Africa.

SAS Maria van Riebeeck’s launching in France

South Africa’s Dafne class submarines never fired a torpedo in anger, however the service was involved in many reconnaissance and clandestine operations in support of special forces during the Border War (1966 to 1989). The submarines also shadowed many a potential hostile nation’s military and navy shipping around the South African cape during the Border War period.

As an interesting aside, the 1970’s also produced another famous South African born submariner in the Royal Navy – Cecil Boyce

Lord Boyce

Admiral of the Fleet, Michael Cecil, Baron Boyce KG GCB OBE KStJ DL was born in Cape Town South Africa and currently is a member of the House of Lords.

Boyce commanded three British submarines, HMS Oberon in 1973, followed by HMS Opossum in 1974 and finally the nuclear submarine HMS Superb in 1979. In 1983 he took Command of a Royal Navy frigate HMS Brilliant.

Thereafter Boyce achieved higher command in the Royal Navy, serving as First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff from 1998 to 2001 and then as Chief of the Defence Staff from 2001 to 2003. In early 2003 he advised the British Government on the deployment of troops for the invasion of Iraq.

HMS Superb

Post 1994

In so far as ‘firsts’ go, the ANC government on its accent to power in 1994 has on many occasions dismissed the entire history of South African’s involved in submarine services, whether South African or British as somehow irrelevant. Within a short time frame they renamed all three Daphne Class submarines after African spears – the SAS Maria van Riebeeck became the SAS Spear, the SAS Emily Hobhouse became the SAS Umkhonto and the SAS Johanna van der Merwe became the SAS Assegai.

Under the ANC epoch, the South African Navy replaced the ageing decommissioned French Daphne Class submarines with updated Type 209/T 1400 ‘Heroine’ Class German made submarines. Returning to the tradition of naming submarines after women, the submarines became the SAS Manthatisi, the SAS Charlotte Maxeke and the SAS Queen Modjadji – all heroines who matter greatly to African Nationalist (ANC) history of South Africa.

SAS Queen Modjadji

As more firsts go the first ‘black’ South African to command a submarine was Commander Handsome Thamsanqa Matsane when he took command a the SAS Queen Modjadji in April 2012.

In Conclusion

History remains history, there is no denying facts or somehow changing it to suit this or that politically inspired take on history – the facts, people and dates remain as truths. South Africa’s naval and submarine history in particular did not start from 1994, nor indeed did it start as some would have it from 1957 when Simonstown ceased to be officially British or from 1975 when Britain finally departed. It started in 1910 when South Africa became a country, and it’s a simple truism – for the first 40 years of the country’s existence, the Royal Navy was South Africa’s default navy, we did not have one, South Africans serving in the Navy served in the Royal Navy – no changing that.

South Africa’s submarine service has its pioneers grounded in the Royal Navy, that’s a fact – over 100 years of this rich history in fact. It is also a fact that many South Africans who have served in the Navy or currently serve in the Navy have no idea as to many of these South African submariners who have served with such distinction – this is represented by the fact that no formal recognition is given to any South African serving in British submarines in South Africa whatsoever, not on memorials, not in history annuals, not at remembrance events – we even get our history wrong when we try and understand ‘firsts’ in this service.

We as South Africans are really remiss in our values if we cannot honour these very special countrymen of ours and remember the supreme sacrifice and bravery they have made on our behalf. By all standards the submarine service qualifies ‘the bravest of the brave’ – and these men are truly the ‘silent’ South African names in the ‘silent service’ and it should be a moral obligation to bring their names into the light and recognise them. It is a sincerely hoped that this article is a first step.

Related Observation Posts and links

Elephant in the Room The South African Navy’s ‘elephant in the room’

South Africans in the Fleet Air Arm South African sacrifice in the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References and large extracts – South Africans in the Submarine Service of the Royal Navy, 1916-1945 By Ross Dix-Peek and South Africa’s fighting Ships Past and Present by Allan Du Toit.

Images – Imperial War Museum and Wikipedia

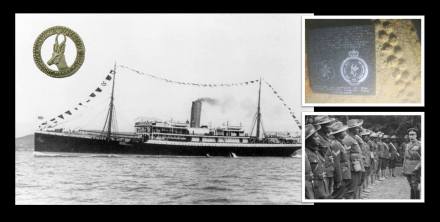

But more often than not only one iconic South African makes it into the distinctive personal memories of tens of thousands of British, South African and other commonwealth soldiers and sailors taking part in the war – and it’s not Jan Smuts, it’s a relatively little known soprano known only as the ‘Lady in White’.

But more often than not only one iconic South African makes it into the distinctive personal memories of tens of thousands of British, South African and other commonwealth soldiers and sailors taking part in the war – and it’s not Jan Smuts, it’s a relatively little known soprano known only as the ‘Lady in White’.

An unsung icon of Liberty

An unsung icon of Liberty

The 2nd of September is a significant day in the history of the world, it’s the day Japan formally surrendered to finally end World War 2. The ceremony took place on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay in 1945, and the South Africans where right there too, represented by Cdr A.P. Cartwright, South African Naval Forces.

The 2nd of September is a significant day in the history of the world, it’s the day Japan formally surrendered to finally end World War 2. The ceremony took place on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay in 1945, and the South Africans where right there too, represented by Cdr A.P. Cartwright, South African Naval Forces.

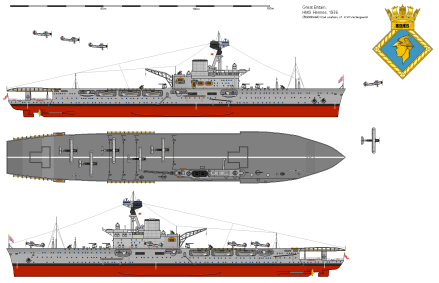

A total of 297 South African Naval Forces (SANF) personnel were killed in action during World War II, and that excludes many South Africans serving directly on British ships as part of the Royal Navy. Many of these South Africans were lost in actions against the Japanese – especially during Japan’s ‘Easter Raid’ against the British Eastern Fleet stationed at Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) which sank the HMS Dorsetshire and HMS Cornwall on the 5th April 1942 and the HMS Hollyhock and HMS Hermes on the 9th April 1942 – with the staggering loss of 65 South African Naval personnel seconded to the Royal Navy and on board these 4 British fighting ships. It was and remains the South African Navy’s darkest hour, yet little is commemorated or know of it today in South Africa, and this is one of the reasons why a SANF official was represented at the formal surrender of Japan.

A total of 297 South African Naval Forces (SANF) personnel were killed in action during World War II, and that excludes many South Africans serving directly on British ships as part of the Royal Navy. Many of these South Africans were lost in actions against the Japanese – especially during Japan’s ‘Easter Raid’ against the British Eastern Fleet stationed at Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) which sank the HMS Dorsetshire and HMS Cornwall on the 5th April 1942 and the HMS Hollyhock and HMS Hermes on the 9th April 1942 – with the staggering loss of 65 South African Naval personnel seconded to the Royal Navy and on board these 4 British fighting ships. It was and remains the South African Navy’s darkest hour, yet little is commemorated or know of it today in South Africa, and this is one of the reasons why a SANF official was represented at the formal surrender of Japan.

Now consider this, we have not even begun to scratch properly at the honour roll, this above list is still highly inaccurate with many names missing. We have no real idea of the thousands of South Africas who volunteered and died whilst serving in The Royal Navy Reserve and the Royal Navy itself, in fact we’ve barely got our heads around it. Fortunately a handful of South Africans are working on it, almost daily, but it’s a mammoth task as these names are found on Royal Navy honour rolls and it’s a matter of investigating the birthplace of each and every British casualty. The records of South African volunteers joining the Royal Navy lost to time really.

Now consider this, we have not even begun to scratch properly at the honour roll, this above list is still highly inaccurate with many names missing. We have no real idea of the thousands of South Africas who volunteered and died whilst serving in The Royal Navy Reserve and the Royal Navy itself, in fact we’ve barely got our heads around it. Fortunately a handful of South Africans are working on it, almost daily, but it’s a mammoth task as these names are found on Royal Navy honour rolls and it’s a matter of investigating the birthplace of each and every British casualty. The records of South African volunteers joining the Royal Navy lost to time really.

MACWHIRTER, Cecil J, Ty/Sub Lieutenant (A), Fleet Air Arm (Royal Navy) 851 Squadron HMS Shah, air crash, SANF, MPK 14 April 1944

MACWHIRTER, Cecil J, Ty/Sub Lieutenant (A), Fleet Air Arm (Royal Navy) 851 Squadron HMS Shah, air crash, SANF, MPK 14 April 1944

WAKE, Vivian H, Ty/Lieutenant (A), FAA Fleet Air Arm (Royal Navy) 815 Squadron HMS Landrail, air crash, SANF, MPK 28 March 1945

WAKE, Vivian H, Ty/Lieutenant (A), FAA Fleet Air Arm (Royal Navy) 815 Squadron HMS Landrail, air crash, SANF, MPK 28 March 1945

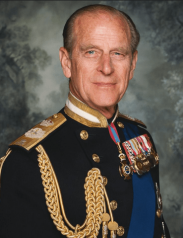

The best way to summarise the Fleet Air Arm, its commitment and sacrifice is in fact found in the forward of Derrick Dickens’ Stringbag to Shar’ written by none other than the Admiral of the Fleet, HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh K.G., K.T., O.M., G.B.E.

The best way to summarise the Fleet Air Arm, its commitment and sacrifice is in fact found in the forward of Derrick Dickens’ Stringbag to Shar’ written by none other than the Admiral of the Fleet, HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh K.G., K.T., O.M., G.B.E.

Here’s a question for many, in what action did the South African Navy (SAN) experience its greatest single loss of personnel, the largest sacrifice of South African life in a single sea battle – in essence when and what was the South African Navy’s ‘darkest hour’?

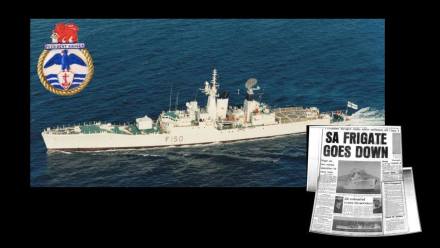

Here’s a question for many, in what action did the South African Navy (SAN) experience its greatest single loss of personnel, the largest sacrifice of South African life in a single sea battle – in essence when and what was the South African Navy’s ‘darkest hour’? Most (actually the majority) of SAN officers and veterans would say it was the loss of the SAS President Kruger (16 souls) but that would also be very wrong, both in terms of scale and action, the SAS President Kruger loss was also an accident at sea and not a combat action.

Most (actually the majority) of SAN officers and veterans would say it was the loss of the SAS President Kruger (16 souls) but that would also be very wrong, both in terms of scale and action, the SAS President Kruger loss was also an accident at sea and not a combat action. These are the HMSAS Southern Floe (24 souls) or the HMSAS Parktown (5 souls), or the HMSAS Bever (17 souls) or the HMSAS Treen (23 souls) – getting warm but that too would be wrong, as these did not happen over a defined period of the war that would warrant a ‘darkest hour’ in Churchill’s definition of the phrase (Churchill coined the term).

These are the HMSAS Southern Floe (24 souls) or the HMSAS Parktown (5 souls), or the HMSAS Bever (17 souls) or the HMSAS Treen (23 souls) – getting warm but that too would be wrong, as these did not happen over a defined period of the war that would warrant a ‘darkest hour’ in Churchill’s definition of the phrase (Churchill coined the term).

So there we have it, the South African Navy’s biggest single loss in a single day – 41 souls, a ‘black day’ and added together with the HMS Hermes and HMS Hollyhock , we see a complete total of 65 South African souls lost in one single engagement at sea – qualifying a very ‘black week’ – The Easter Sunday Raid and this then marks the Easter period as the South African Navy’s ‘Darkest Hour’.

So there we have it, the South African Navy’s biggest single loss in a single day – 41 souls, a ‘black day’ and added together with the HMS Hermes and HMS Hollyhock , we see a complete total of 65 South African souls lost in one single engagement at sea – qualifying a very ‘black week’ – The Easter Sunday Raid and this then marks the Easter period as the South African Navy’s ‘Darkest Hour’. This Easter we also remember Rear Admiral Guy Hallifax, the most senior South African Naval officer to lose his life during World War 2. His contribution to the Navy is significant as he literally is one of the founding fathers of the modern South African Navy as we know it.

This Easter we also remember Rear Admiral Guy Hallifax, the most senior South African Naval officer to lose his life during World War 2. His contribution to the Navy is significant as he literally is one of the founding fathers of the modern South African Navy as we know it.

The HMS Dorsetshire was a heavy cruiser and after commissioning in 1930 became the flagship of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron Atlantic Home Fleet. Before the war, from 1933 until 1936, HMS Dorsetshire served on the Africa Station. Her first recorded docking in the Selborne dry dock at Simonstown, South Africa was on 5 January 1934.

The HMS Dorsetshire was a heavy cruiser and after commissioning in 1930 became the flagship of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron Atlantic Home Fleet. Before the war, from 1933 until 1936, HMS Dorsetshire served on the Africa Station. Her first recorded docking in the Selborne dry dock at Simonstown, South Africa was on 5 January 1934.

BELL, Douglas S, Ty/Act/Leading Stoker, 67243 (SANF), MPK

BELL, Douglas S, Ty/Act/Leading Stoker, 67243 (SANF), MPK Their names have not been forgotten.

Their names have not been forgotten.

HMS Cornwall was a heavy cruiser of the Kent-subclass of the County-class. When World War 2 began in September 1939, Cornwall was transferred from her pre-war China Seas operations to the Indian Ocean and joined Force I at Ceylon.

HMS Cornwall was a heavy cruiser of the Kent-subclass of the County-class. When World War 2 began in September 1939, Cornwall was transferred from her pre-war China Seas operations to the Indian Ocean and joined Force I at Ceylon.

Suddenly there was an almighty explosion that seemed to lift us out of the water, the after magazine had gone up, then another, this time above us on the starboard side, from that moment onwards we had no further communication with the bridge which had received a direct hit, as a result of that our Captain and all bridge personnel were killed.

Suddenly there was an almighty explosion that seemed to lift us out of the water, the after magazine had gone up, then another, this time above us on the starboard side, from that moment onwards we had no further communication with the bridge which had received a direct hit, as a result of that our Captain and all bridge personnel were killed. South African casualties aboard HMS Hermes

South African casualties aboard HMS Hermes