The German orphan program to boost the white Afrikaner ‘volk’ bloodline

This story verges on the bizarre, but the funny thing is that it’s true and you just can’t make this sort of thing up when it came to South Africa’s old Afrikaner Nationalists. This was a program initiated by right wing Nationalists after World War 2 (1939-1945) to boost the white Afrikaner ‘bloodline’ by importing 10,000 hand-picked German ‘Herrenvolk’ orphans to South Africa for adoption. It is another example of the extreme type of ‘social engineering’ embarked on the by the Afrikaner Nationalists and it underpins the ideologies and thinking that were beginning to formulate in the National Party post war.

The idea carried obvious benevolence to adopt displaced German children who had lost both parents during the war, so in that respect it held a certain moral high-ground, however it is in the objectives and the methodology used that we find sinister Weimar Eugenics at play, the implementation of Nuremberg Race Law ideology, political protest and the manipulation of demographics to advance political gain.

Had the program attained its full quota and objectives, the ‘boost’ to the white Afrikaner pool would have been significant in the three odd generations to come after World War 2. If population growth is anything to go by, in three generations we would be nearing half a million extra white Afrikaners with Aryan German heritage with roots this post war orphan program. As pointed out by Werner van der Merwe in his UNISA journal in 1988, its impact and commemoration would now rival the millennial Second World War anniversary, the French Huguenot anniversary or the next millennial anniversary of the Great Trek.1

Clearly in 2024 we can conclude that this seismic shift in white Afrikaner demographics did not take place, and the reason is this quota of 10,000 ‘Aryan’ orphans was never reached, but that’s not to say the attempt was not made, the program did exist and it had some successes and failures of which there are good underpinning reasons for both. So let’s have a look at the Afrikaner Nationalist’s Dietse Kinderfonds (DKF) – the German Children Fund, its background and its purpose.

Background on the Nazification of the Afrikaner right

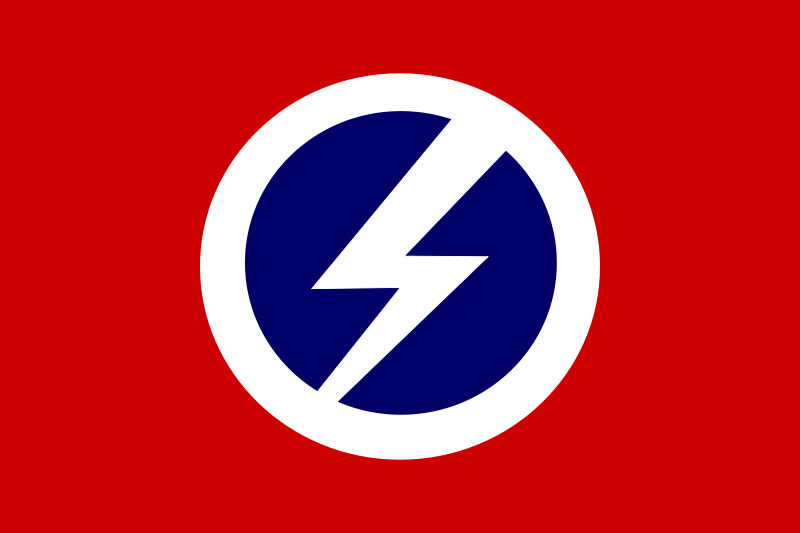

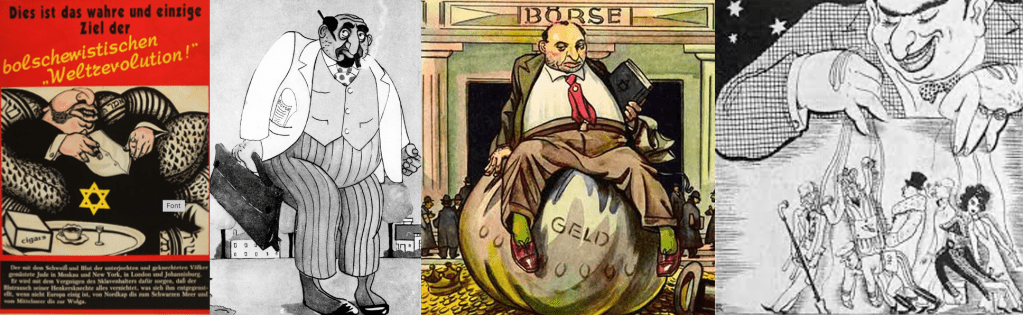

In South Africa, this particular story starts the inter-war years (1918-1939), with the rise of National Socialism in Germany and Fascism in Italy from the mid 1920s, many Afrikaner Nationalists increasingly came under the influence of Adolf Hitler and his specific brand of German National Socialism (Nazism). Oswald Pirow, Prime Minister Barry Hertzog’s Minister of Defence (1933-1939), was one of the most influential Afrikaners to fall under Hitler’s spell. Pirow met with Hitler, Hermann Göring, Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco as an envoy on behalf of the United Party government2. Pirow received Nazi Germany’s feedback on German South West Africa and the ‘new order’ should Germany go to war with Britain and her allies. Pirow gambled his career on a Nazi Germany victory in what he saw as an inevitable war. On 25 September 1940, he founded the national socialist ‘New Order’(NO) for South Africa. He positioned it as a study group within the reformulated National Party (HNP), and based it on Hitler’s new order plans for Africa3. In terms of the NO’s values, Pirow espoused Nazi ideals and advocated an authoritarian state4.

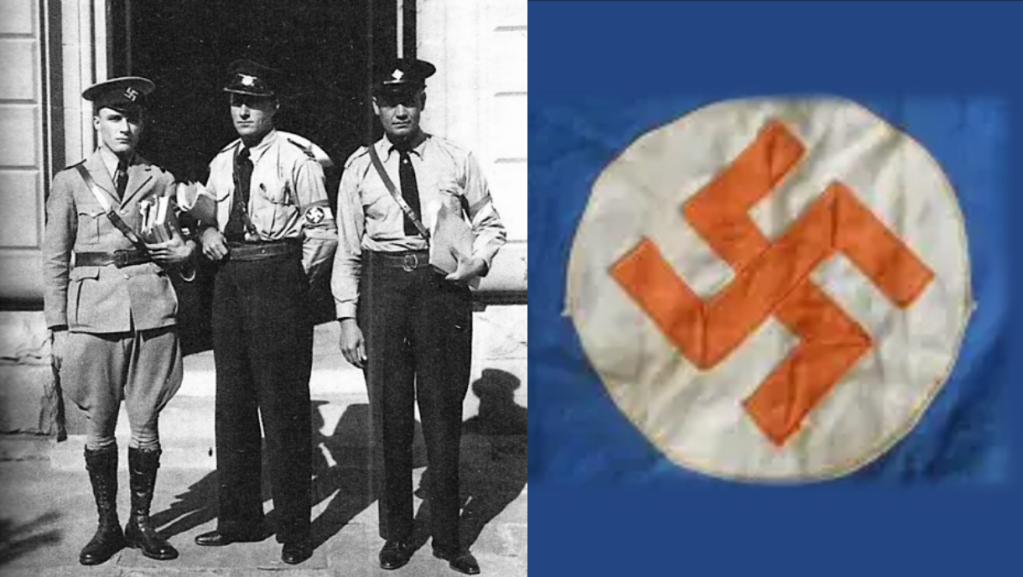

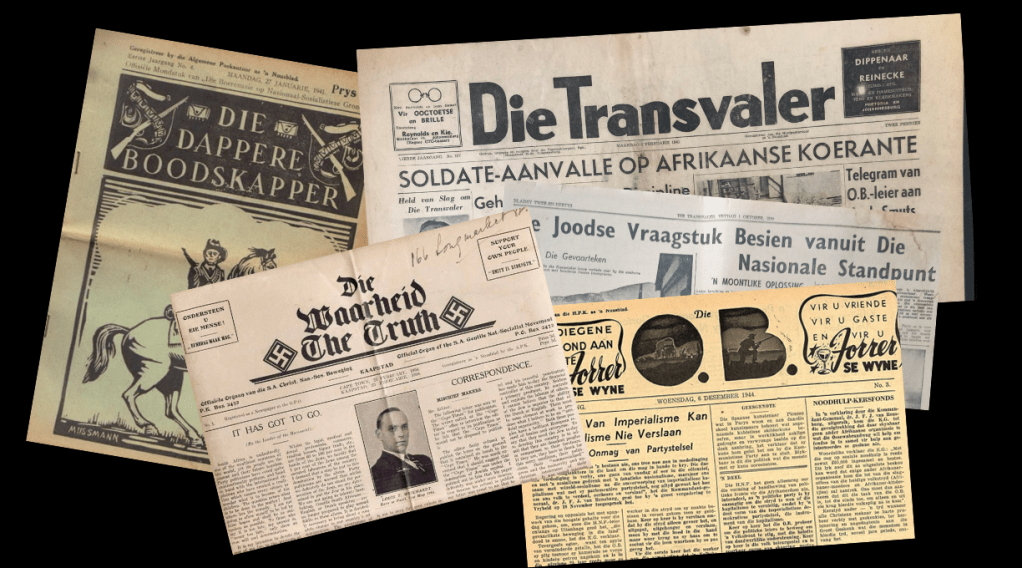

In addition to Oswald Pirow’s NO, other leading and influential Afrikaner Nationalists were forming German National Socialist movements in South Africa during the interwar period. As a committed antisemite, Louis Weichardt broke with the National Party on the 26 October 1933. He founded South Africa’s Nazi party equivalent – The South African Christian National Socialist Movement. This included a paramilitary ‘security’ or ‘body-guard’ section (modelled on Nazi Germany’s brown-shirted Sturmabteilung) called the “Gryshemde” or “Grey-shirts”. In May 1934, the Grey-shirts merged with the South African Christian National Socialist Movement and formed a new enterprise called ‘The South African National Party’ (SANP). The SANP would continue wearing Grey-shirts as their identifying dress and would also make use of other Nazi iconography, including extensive use of the swastika5. Overall, Weichardt saw democracy as an outdated system and an invention of British imperialism and Jews6.

Other neo-Nazi and fascist groupings either spun out of the SANP Grey-shirts, or mushroomed as National Socialists movements with the German model front and centre in their own right. Also included was Manie Wessels’ ‘South African National Democratic Movement’ (Nasionale Demokratiese Beweging) known as the “Black-shirts”. The Black-shirts themselves would splinter into another Black-shirt movement called the ‘South African National People’s Movement’ (Suid Afrikaanse Nasionale Volksbeweging, started by Chris Havemann and based in Johannesburg, these Black-shirts advanced a closer idea of National Socialism7. Another National Socialist movement known as the ‘African Gentile Organisation’ was also formed in Cape Town by HS Terblanche. In September 1934, Dr AJ Bruwer formed the ‘National Workers Union’ (Bond van Nasionale Werkers) in Pretoria – also known as the “Brown-shirts”. Additionally, Frans Erasmus formed another national party militant group called the “Orange-shirts”8.

In a leadership purge, three National Socialist movements broke away from the SANP Grey-shirts, SANP leader JHH de Waal resigned and formed the ‘Gentile Protection League’ whose sole aim was to fight the ‘Jewish menace in South Africa9’ Johannes von Moltke, Weichardt’s right hand man broke away from the SANP and formed a new organisation called ‘The South African Fascists’ who wore Nazi iconography, blue trousers, and Grey-shirts.

Additionally, Manie Maritz, a veteran of the South African War and influential leader of the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion, also admired German National Socialism and split from his association with the SANP Grey-shits and joined Chris Havemann’s Black-shirts. A converted antisemite, Maritz even blamed the South African War on a Jewish conspiracy. Moving from the Black-shirts Martiz founded the anti-parliamentary, pro National Socialist, antisemitic ‘Volksparty’, in Pietersburg in July 194010 This evolved and merged into ‘Die Boerenasie’ (The Boer Nation), a party with National Socialist leanings originally led by JCC Lass (the first Commandant General of the Ossewabrandwag) but briefly taken over by Maritz until his accidental death in December 1940.

Aside from all these various parties, the Ossewabrandwag (OB, the Ox-Wagon Sentinel) was the largest and most successful Afrikaner Nationalist organisation with pro-Nazi sympathies prior to and during the Second World War. The Ossewabrandwag was formed on the back of the 1938 Great Trek Centennial celebration – the centennial was planned under the directive of the “Afrikaner Broederbond” (Brotherhood) and championed by its Chairman, Henning Klopper. They sought to use the centenary anniversary of the 1828 Great Trek to unite the “Cape Afrikaners” and the “Boere Afrikaners” under the pioneering symbology of the Great Trek and to literally map a “path to a South African Republic” under a white Afrikaner hegemony. The trek re-enactment was very successful, and Klopper managed to realign white Afrikaner identity under the Broederbond’s Christian Nationalist ideology calling on providence and declaring it a ‘sacred happening’ 11.

The OB was tasked with spreading the Broederbond’s (and the PNP’s) ideology of Christian Nationalism like “wildfire” across the country (hence the name Ox wagon “Firewatch”’ or “Sentinel”). The OB’s national socialist leanings are seen in correlation with other world ideologies of the time, and specifically to that of Nazi Germany12 . Afrikaner Christian Nationalism, although grounded in “Krugerism” as an ideology, can be regarded as a derivative of German National Socialism and Italian Fascism and is identified as such by OB leaders like John Vorster in 194213. Earlier, the future leader of the OB, Dr Hans Van Rensburg, whilst a Union Defence Force officer, had met with Adolf Hitler and became an avowed admirer of both Hitler and Nazim. As leader of the OB, he then later infused the organisation with National Socialist ideology, whereafter the organisation took on a distinctive fascist appearance, with Nazi ritual, insignia, structure, oaths and salutes.

Ideologically speaking the OB adopted a number of Nazi characteristics: they opposed communism, and approved of antisemitism. The OB adopted the Nazi creed of “Blut und Boden” (Blood and Soil) in terms of both racial purity and an historical bond and rights to the land. They embraced the “Führer Principle” and the “anti-democratic” totalitarian state (rejecting “British” parliamentary democracy). They also used a derivative of the Nazi creed of “Kinder, Küche, Kirche” (Children, Kitchen, Church) as to the role of women and the role of the church in relation to state. In terms of economic policy, the OB also adopted a derivative of the Nazi German economic policy calling for the expropriation of “Jewish monopoly capital” without compensation and adding “British monopoly capital” to the mix14.

By the early 1940’s the OB gained its own militaristic wing, called the “Stormjaers”, who countered the South African war effort through sabotage of infrastructure and targeting Jewish businesses. The OB during the war also directly aided the Nazi war efforts aimed at sedition, espionage, spy smuggling, and collecting intelligence in the Union. The post-war Barrett Commission investigation into South African renegades even contains a personal confession ‘van Rensburg vs. Rex’ as to van Rensburg’s regular and treasonous collaboration with Nazi Germany over a set period of time during the war15.

By July 1939, the Black-shirts were formally incorporated into the OB and focussed on the recruiting of “Christian minded National Aryans” into the OB infusing it with more National Socialist “volkisch” Nationalism. This took the OB well beyond its original intention of functioning as a wholesome cultural organ of Afrikanerdom and the National Party16.

The quest for bloodline purity

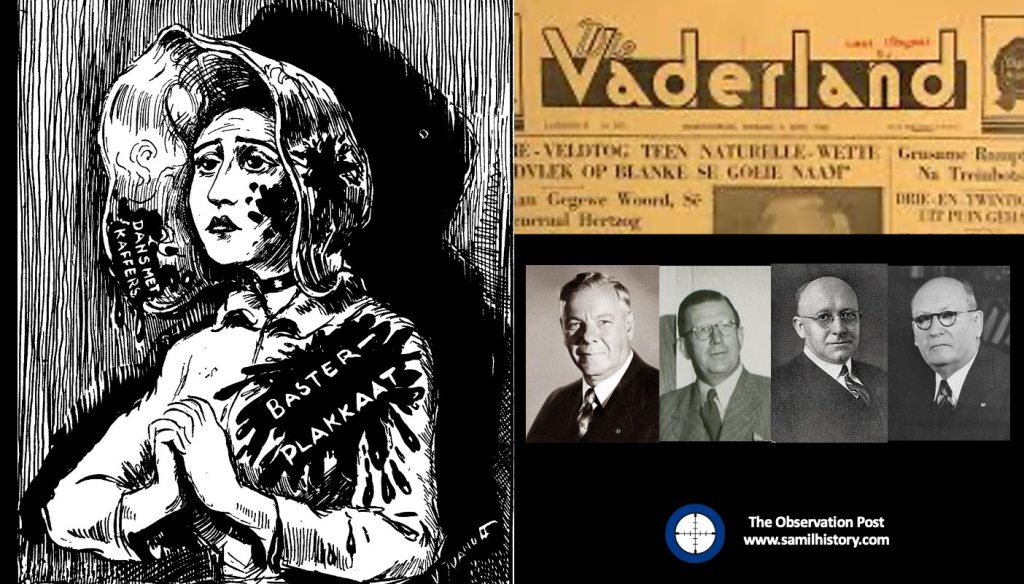

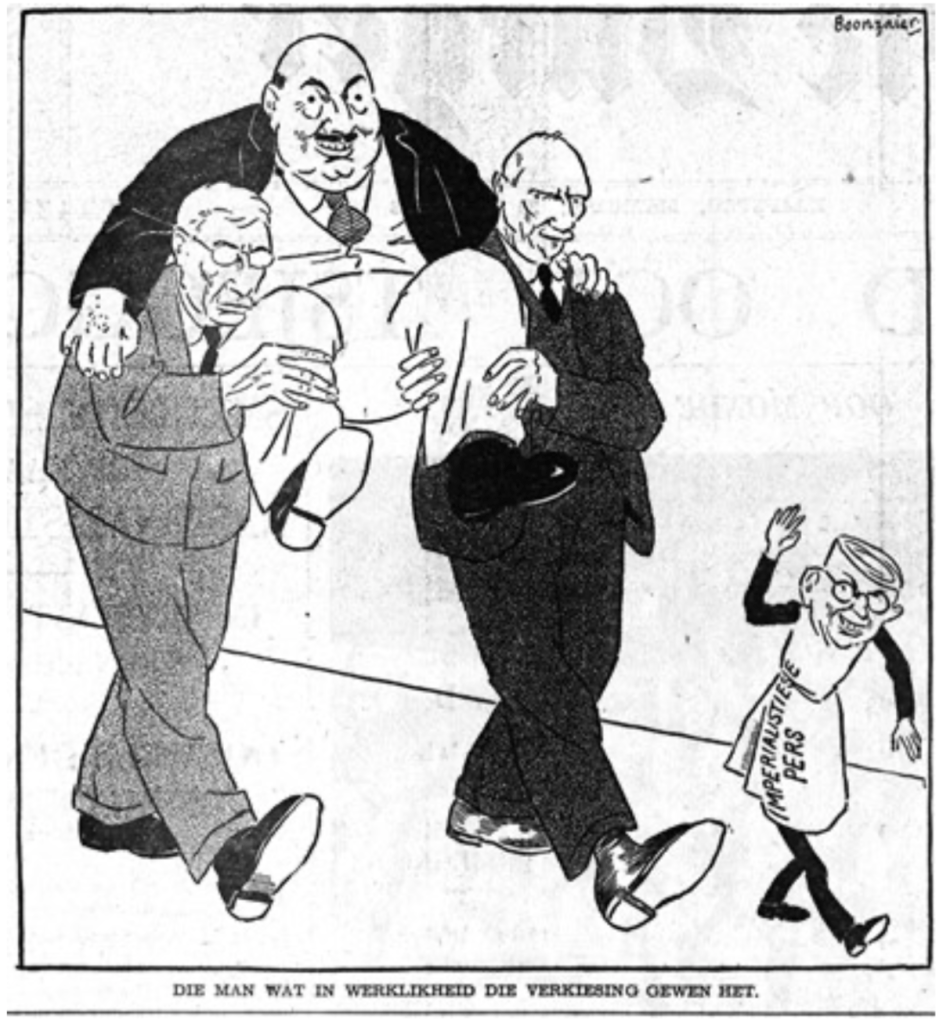

On the National Party front, the ‘Baster Plakaat’ appeared in the ‘Die Vaderland’ – the National Party’s mouthpiece and the sister newspaper to ’Die Transvaaler’. It appeared on 12 May 1938 and marks the trigger point where ‘Race Law’ starts to enter into National Party thinking from the political front. It marks the advent of a combination of the Nazi Nuremberg Race laws (which banned ‘mixed’ blood marriages of different races and Jews) and Jim Crow American segregation laws (the separation of blacks and whites on which the Nazi German lawyers based their Nuremberg Laws).

The political illustration, known as the “Baster Plakkaat” (miscegenation) released a torrent of criticism and became a media sensation of its time, it caused a lot of discontent between the United Party and the Pure National Party – and for good reason. The essential Law at play in the National Party media mouthpieces is the Nazi law – The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour – propagated in 1935. In the context of the Afrikaner Nationalist mouth-piece this finds expression in a ‘Pure’ Voortrekker woman, in prayer to God and in ‘pure’ white traditional kappie and dress – now “tainted” with “Kaffir” blood, the words ‘dans met Kaffirs’ (dances, i.e to have sexual relations with the black native ‘Kaffirs’) writ in blood … a warning to keep races apart and prevent intercourse lest the purity of soul and the honour of white Afrikanerdom is compromised17.

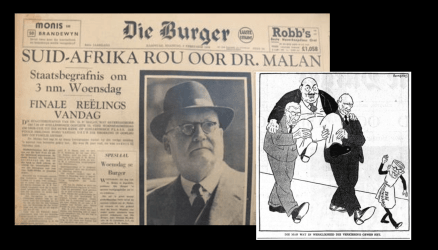

It marks the coming together of two distinctive factions in the National Party. On the one hand the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk (NGK) or Dutch Reformed Church, the “Dominees” (Preachers) in the National Party like Dr. D.F. Malan, whose 1931 – Orange Free State Synod rejects social equality with Blacks and declares Blacks should develop ‘on their own terrain, separate and apart’18 – the idea of mixed marriages and soiling the bloodline of ‘pure’ white Afrikaners discouraged by the NGK. Dr. Malan is also one of the first editors of ‘Die Burger’ another Afrikaner Nationalist mouthpiece.

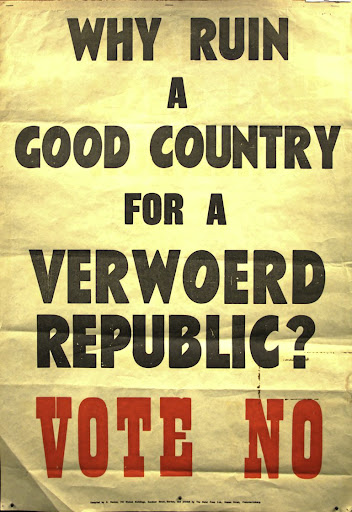

On the other hand are the Afrikaner “Germanophiles” in the National Party, the ones in open admiration of Hitler and Nazi Germany in the late 1930’s and in lock step with German thinking on race. They all fall part of the National Party’s political think tank, all academic intellectuals – these are primarily Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd (the editor of ‘Die Transvaaler’ and Sociologist), Dr. Nico Diederichs (the Chairman of the Broederbond and Political Scientist) and Dr. Eben Dönges (‘Die Burger’ journalist/lawyer who introduced race-based population registration).

These are the collectively known as “architects” of Apartheid and it is no surprise given that they all hold positions as editors that the kernel of “race law” thinking – both on the political and theological fronts starts to formulate in the Nationalist media.

Aryan Immigrants only

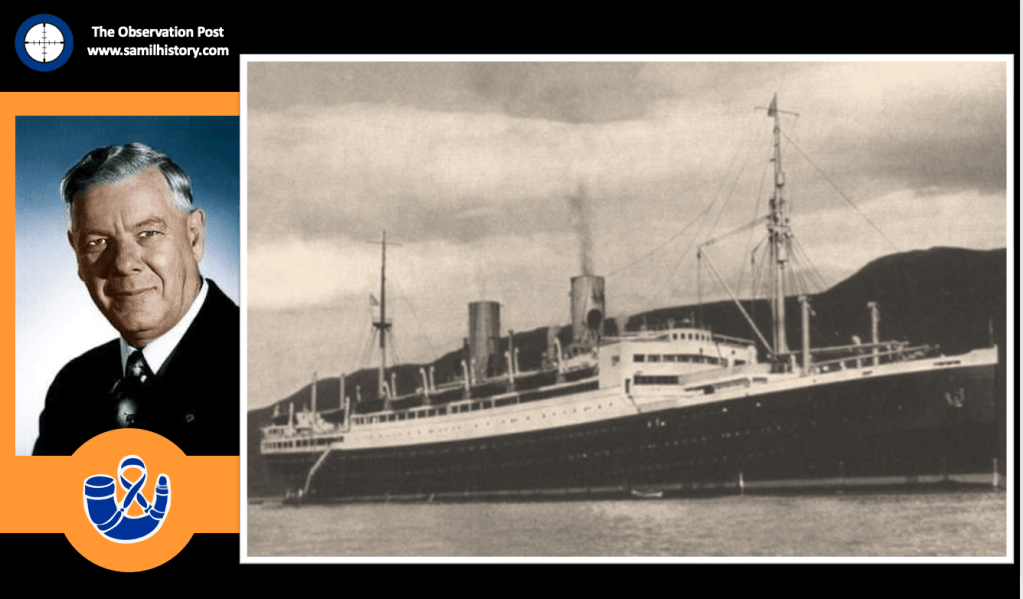

Insofar as Afrikaner “Germanophiles” collaboration and co-operation with Nazi Germany. Prior to the war the Pure National Party was in the process of framing up its policies. The arrival of the S.S. Stuttgart in Cape Town on the 27th October 1936 packed with 537 Jewish refugees on board19 sharply brought the National Party’s policies of immigration and race into focus – it defined what sort of ‘demographics’ the Pure National Party were prepared to focus on to augment the ‘white races’ in South Africa and which were the ‘undesirables’. The arrival of the SS Stuttgart was met with a mass protest of some 3,000 South African Nazi ‘Grey-shirts’20.

Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd was Dutch by birth, but he honed his studies in sociology and psychology in Germany and there is no doubt he was exposed to German politics and the rise of Nazism. Verwoerd showed his antisemitic colours early on when he and a deputation of four fellow minded Nationalist academics – Christiaan Schumann, Dr. Johannes Basson and Dr. Eben Dönges from Stellenbosch University and Frans Labuschagne of Potchefstroom University joined hands with the Nazi Grey-shirts and lodged protest with Hertzog’s’ government as to the immigration of Jews from Nazi Germany.21 At this point these academics were concerning themselves with the poor white problem and ‘völkisch‘ mobilisation warning that Jews were ‘unassailable‘ to the Afrikaner Volk , they met to protest the SS Stuttgart at the University of Stellenbosch on 27 October 1936 and resolved that Jews were ‘undesirable‘ on account of ‘religion’ and ‘blood mingling‘ and that ‘cultural cooperation‘ with them was impossible22.

Frans Erasmus (the future National Party Minister of Defence) would go further on the matter and even officially thank the Grey-shirts on behalf of The National Party for bringing the attention of the ‘Jewish problem to the Afrikaner volk.‘ This in turn spurred Dr. DF Malan to table an Immigration and Naturalisation Bill which sought to exclude immigrants who were ‘unassailable‘ with the culture and even economics of the Afrikaner Volk and deal with ‘the Jewish problem’ as he termed it. This in turn led to the ‘Aliens Bill’ being passed in 193723 by the Hertzog led United Party government which although a watered down version of Malan’s original proposal, still pandered to issue of cultural and economic ‘assimilation’ to prevailing ‘European’ white culture in South Africa – opening the way for the “right kind” of European immigrants (the Aryan kind) and not the wrong kind (the Jewish kind).

The Clouds and Fog of War

With the clouds of war looming in 1939, on the right of Afrikaner political spectrum, all the various movements with Nazi ideologies and/or pro Nazi war effort sympathies inherent in them, the main ones being the New Order, the Grey-Shirts, the Ossewabrandwag, and the Purified National Party with its combination of “Dominees” and think tank “Afrikaner “Germanophiles”, all found themselves in lock step with Nazi Germany.

Enough so that Dr. Nico Diederichs on 9 May 1939, in his capacity of the Chairman of the Broederbond, would meet Herr. H. Kirchner, a Nazi foreign ministry representative in South Africa. Diederichs assures Kirchner that the divisions in Afrikanerdom had been overcome by the purging of Freemasons from Broederbond (which he had personally seen to) – he would go on to say that the Pure National Party (PNP) was a committed anti-semitic party and as policy had hung its hat on it, he assures Kirchner that despite recent statements by Dr DF Malan, Malan is also a committed anti-semitic. Diederichs however feels that more needs to be done to frame up National Party policies in line with National Socialism and confides in Kirchner that he does not think Dr. DF Malan is the man to do it, rather the implementation of the ‘anti-democratic’ and other national socialist principles should he left to Dr. Hans van Rensburg (a PNP member in the Orange Free State and the leader of the Ossewabrandwag) who he also feels would be ideal leader of the Purified National Party going forward24.

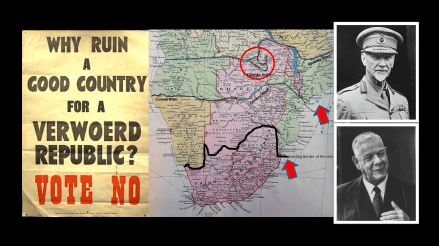

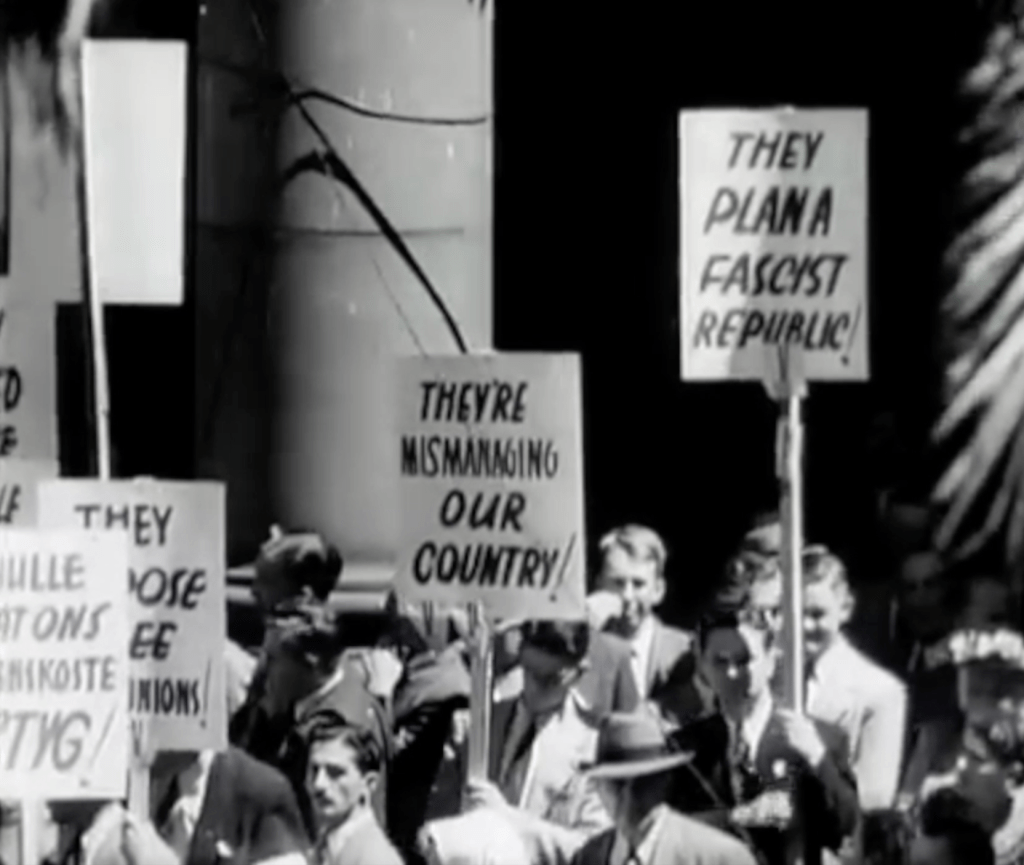

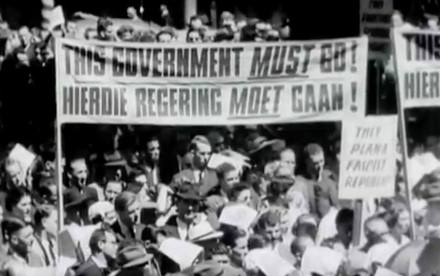

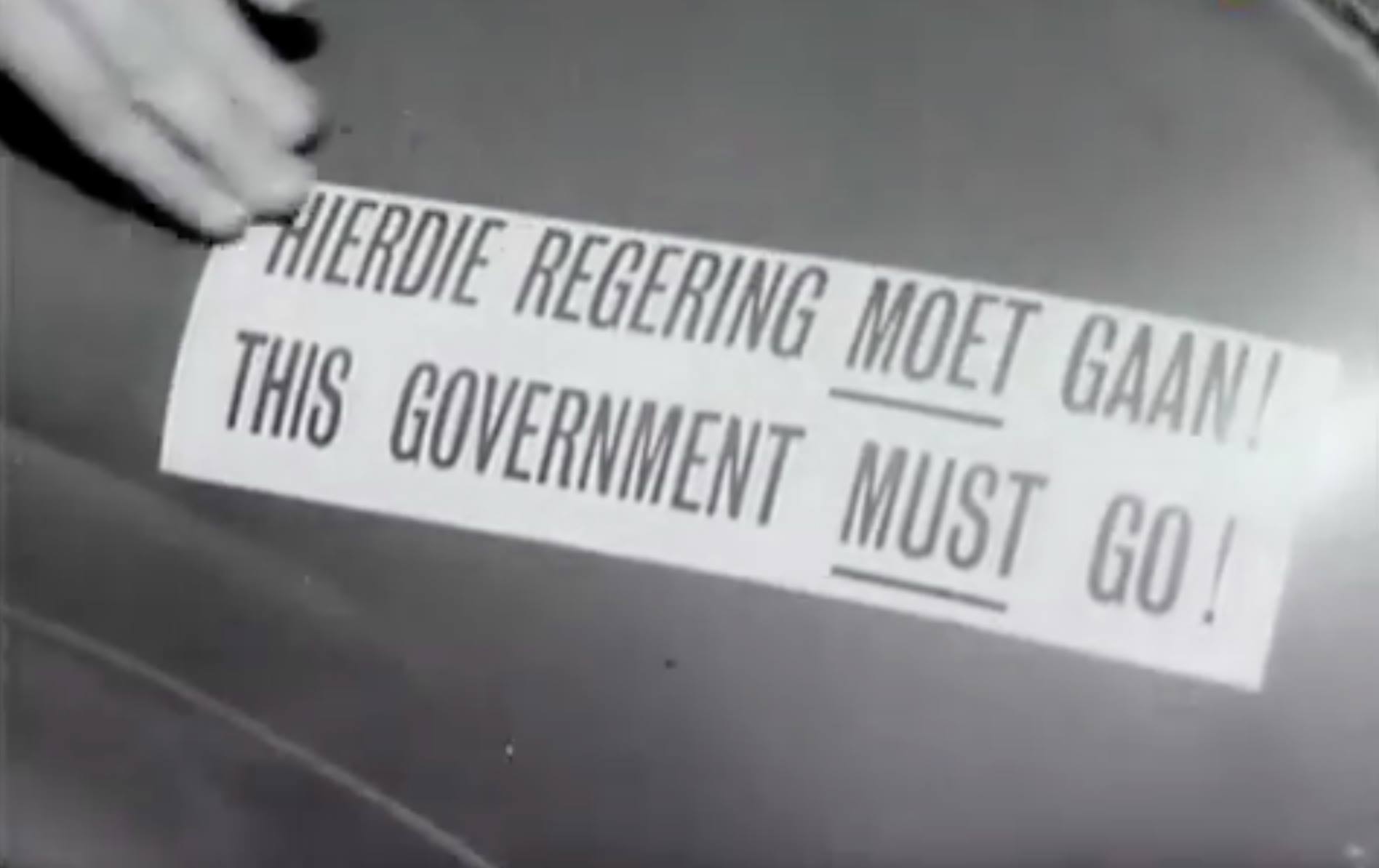

In South Africa the overt and even tacit support for Nazi Germany in the white Afrikaner community became openly apparent when Britain and France declared war against Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939. The Hertzog led United Party found itself in a dilemma and a parliamentary three-way debate would take place almost immediately after Britain’s’ declaration. This debate, primarily between the two factions in the United Party (Hertzog’s old National Party cabal and Smut’s old South African Party cabal) and the Purified Nationalists, was whether South Africa should go to war against Germany or remain neutral. General Smuts’ argument surprisingly won the day and Smuts’ amendment to Hertzog’s Motion of Neutrality was carried by 80 votes to 67 votes on the 4 September 1939, and as a result South Africa found itself at war against Nazi Germany. Surprised at the outcome, Hertzog promptly resigned and along with 36 of his supporters left the United Party, thereby leaving the South African Premiership and the leadership of the United Party to Smuts25.

The Purified National Party’s “Malanites” (with its Dominees and its academic think tank Germanophiles) and the United Party’s old National Party fusion “Hertzognites” were able to ultimately reconcile their differences sans Hertzog, all under the leadership of Dr. DF Malan and they reconstituted themselves as the Herenigde Nasionale Party (Reunited National Party) HNP on 29 Jan 1940.

Dr. Malan took a position to remain officially ‘neutral’ as to South Africa’s role in the war, whilst at the same time tacitly approving the Nazi war effort and hoping for their victory. Among the Afrikaners who opposed the war with Nazi Germany, many legally directed their outrage through political expression26 in the HNP. Various splinter group cultural organisations like the Ossewabrandwag and political entities like the Grey-shirts and the New Order surrounding the National Party took a different approach and overtly engaged High Treason activities in support of Nazi Germany’s war effort. These activities were subversive and clandestine actions by nature and aimed at disrupting the South African war effort through bombings, sabotage and intimidation. The Ossewabrandwag’s militant wing Stormjaers were responsible for many of these actions of sabotage, but other groups, such as the Tereurgroep, the x-Group and Robey Leibbrandt’s National Socialist Rebels, were equally active.27

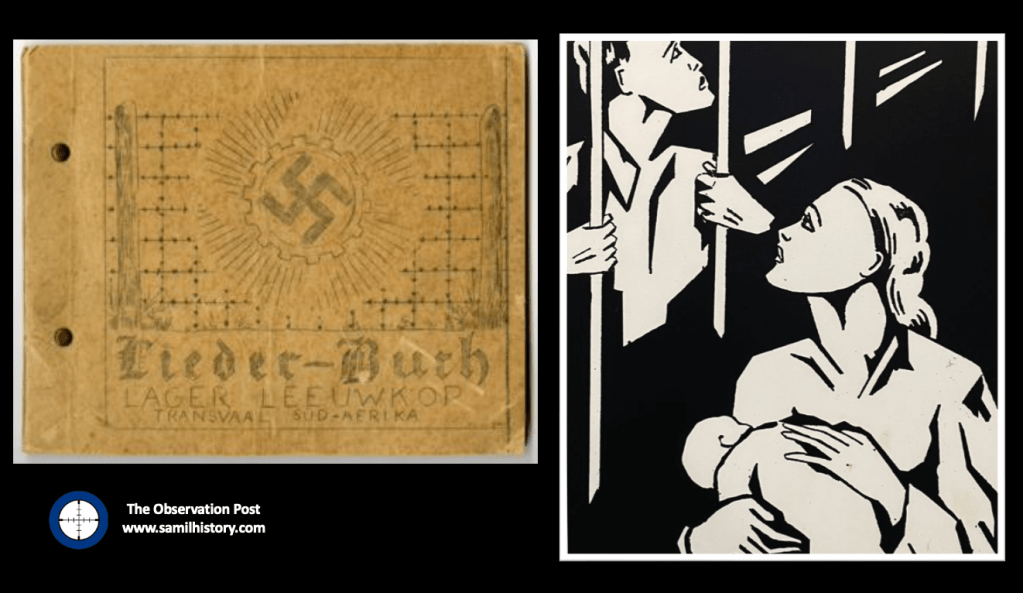

Smuts’ wartime government issued Proclamation 201 of 1939 and the War Measures Act of 1940 (Act 13 of 1940), which provided the government with arbitrary powers for the suppression of subversive organisations and declared them illegal if they presented a danger to the defence of the Union and the Mandated Territory (SWA), public safety and order and the conduct of war28. The suppression of the right wing Afrikaner nationalists involved in sedition, treason and sabotage became a necessity, suspects were held under the Act without trial and interned along with enemy spies and foreign nationals suspected of subversive acts. They were held at six internment camps, namely Baviaanspoort, Leeukop, Andalusia, Ganspan, Sonderwater and Koffiefontein during the war. Col. EG Malherbe, Director of Military Intelligence, noted in his biography that 6,636 people (including POW and German Nationals) were interned during the war29.

Of the “political prisoners” interned, the generally accepted number is approximately 2,000 right wing white Nationalists, some future famous names include BJ Vorster (an OB General and future Prime Minister of South Africa), his brother, the Rev. Koot Vorster (an OB General and NGK stalwart), Louis Theodor Weichardt – the leader of the SANP Grey-shirts and Hendrik van den Bergh (an OB stalwart and the future head of the Apartheid regime’s division of State Security).

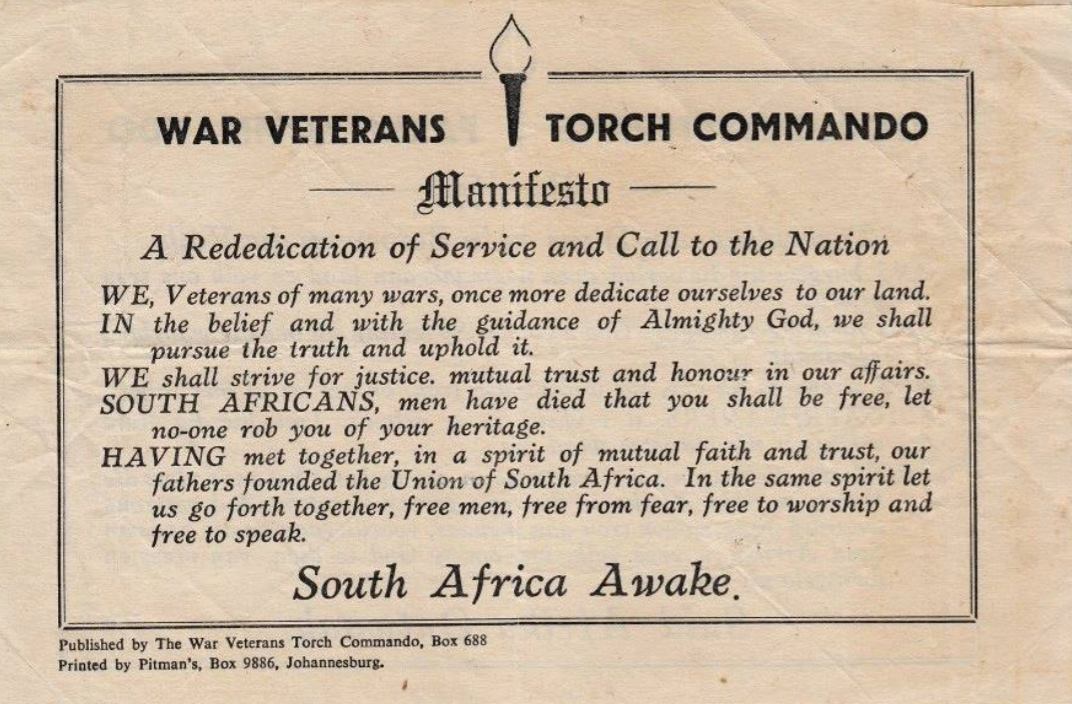

Post War Reconciliation

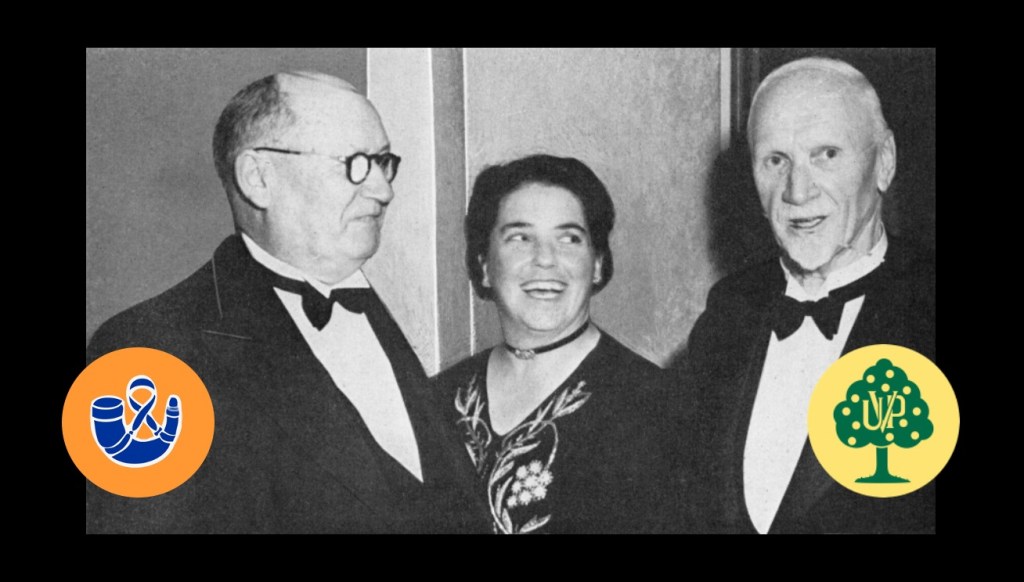

At the end of the Second World War, with Nazi Germany’s fate sealed on 7 May 1945, the issue of German National Socialism (Nazism) and Italian Fascism as a viable political undertakings in South Africa became moot. The peripheral Neo Nazi and fascist ‘shirt’ movements, National Socialist ‘volks’ parties, the New Order and the Ossewabrandwag were all gradually welcomed into the Reunited National Party (HNP) under Malan and the Afrikaner Party under Nicolaas Havenga.

Unlike other Allied partners in the war effort against Germany, the Smuts government took a cautious and reconciliatory approach to all its dissonant and irreconcilable white Afrikaner voters who had supported Germany due to cultural and political affiliations prior to and during the war. This affinity for Germany stemmed from the many Afrikaners who had German ancestry as a result of Germans settling in South Africa that by the nineteenth century 33.4% of Afrikaners were of German ancestry, 35.5% of Dutch ancestry, 13.9% of French ancestry, 2.9% of British ancestry and 14.3% of other nations30. As a voter block in a whites dominated franchise this presented a significant demographic to Smuts, and one whose support he needed to remain in power.

Inside South Africa the Nazis had failed in the short-term, but the success of the pro-Nazi and anti-war groupings planted a fertile seed bed for the future authoritarianism of the Apartheid state. The constant depreciation of liberal democracy in this demographic of Afrikaners alongside an almost ‘hysterical exaltation’ for both ‘racist’ and a ‘Völkisch‘ group ethics were to have long term effects31. In essence, although Nazi ideology and dogma was no longer permissible in the political sphere, no measures were put in place by the Smuts government to prevent it from flourishing. Afrikaner Nationalists entertaining strong National Socialist ideologies and having committed high treason and sedition, who in European countries would have been hanged for war crimes, landed up back in mainstream party politics under the banner of the National Party and many even ended their days in Parliament32.

Reigniting Herrenvolk and Weimar Eugenics

Regardless of the outcome of World War 2, Afrikaners who had come under the influence of National Socialist dogma still held Germany in such high esteem that they were prepared to do everything in their power to ensure that the Afrikaners would benefit from Germany’s defeat in 1945 by obtaining for the Afrikaner Volk some of the “valuable blood of the German Herrenvolk”33.

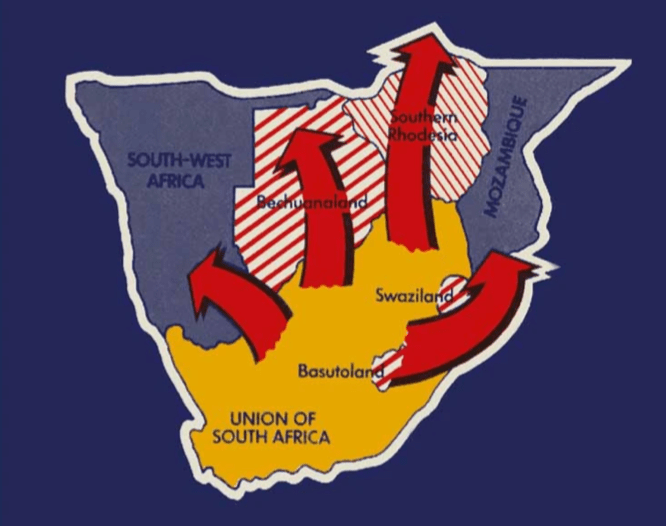

Before and during the war Nazi German emissaries and agents had promised both Dr. DF Malan and Dr. Hans van Rensburg that Germany would help them to establish an Afrikaner hegemony state in Southern Africa along oligarchy and racially differentiated lines, this would include all of South Africa and the British colonies and protectorates of Swaziland, Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Bechuanaland (Botswana) and Lesotho – but it would exclude German South West Africa (Namibia) which they insisted South Africa return to Germany.

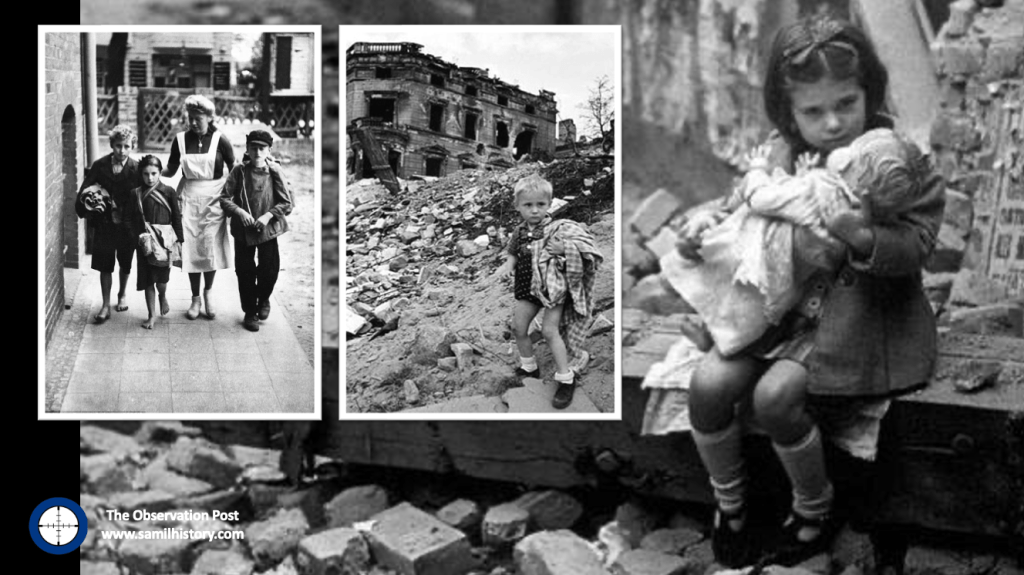

The idea of the re-establishment of the old Boer Republics and the realisation of the vision of an ‘Afrikaans Empire from the Zambezi to the Cape’, a plan announced publicly by senior officials of the ZAR government and Afrikaner bondsmen as early as 188434 – this plan was highly appealing to Afrikaner nationalists. So too was the addressing of the long held animosity to Britain and redressing the loss of the Boer ‘fountain of youth’ in the concentration camps during the South African War – a total of 22,074 children under the age of 1635 (the majority of whom had died of an measles epidemic which swept the camps, the rest succumbing to other diseases – mainly typhoid) . In both instances Nazi Germany would be the enabler of this vision and replenishment of white Afrikaner sovereignty should they win the war – boosted somewhat by the immigration of German ‘Ayans’ to Southern Africa. The outcome of the war did not change this sentiment, vision or objective. Dr DF Malan still pledged that Aryan German immigrants were necessary to cultivate a ‘broad Nordic front to counter Communism, Blacks and Jews’36.

To realise this vision in South Africa post war, the DAHA (Deutsch Afrikanischer Hilfsausschuss) and the VNLK (Women’s Lending Committee) operating under the oversight of the ‘Broederbond’ gathered a quarter of a million pounds between 1945 and 1957 to undertake emergency relief work in post-war Germany. Mrs. Nellie Liebenberg from the VNLK and a previous member of Oswald Pirow’s New Order, alongside her friend Dr. TEW Schumann propose a mission to Germany with the aim of identifying 10,000 handpicked ‘elite’ Aryan orphans and relocating them to South Africa and ‘strengthen their own Afrikaner Volk with the blood of “prestigious” German-Aryan Herrenvolk’37.

This plan to adopt a large number of Nazi war orphans fell under the authority of Dr. Vera Bührmann and Dr. Schalk Botha, and was called the Duitse Kinderfonds (German Children’s Fund), the DKF, once established it attracted huge support the Afrikaner Nationalist elite.

As Werner van der Merwe (an adopted child in the DKF program himself) would summarise in his paper:

‘Some organisations such as the New Order and the Ossewabrandwag overtly favoured a Nazi-like anti-democratic ‘Volkstaat’ for South Africa. It is therefore not surprising that these people were shocked, and even felt betrayed by the Smuts government, when Germany was defeated in 1945. The idea to bring German orphans to (South Africa) was therefore a kind of protest against the defeat of Germany and against South Africa’s participation in the war on the side of Britain. Furthermore, most of the founding members of the DKF were staunch members of either the New Order or the Ossewabrandwag.38‘

The German Children’s Fund (DKF)

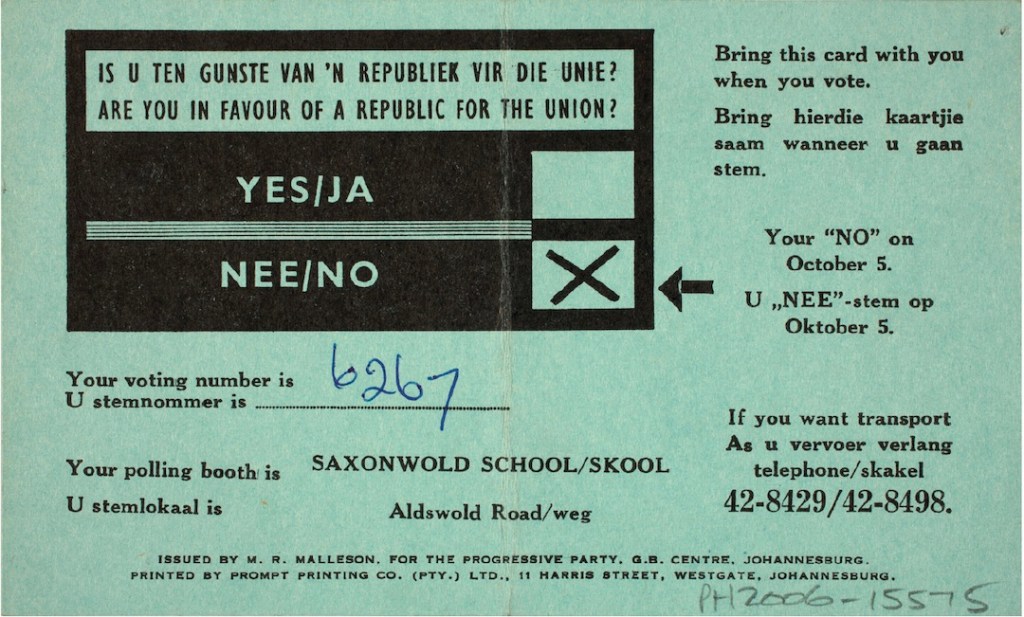

Schalk Botha and Dr. Vera Bührmann (a medical doctor tasked with checking the orphan’s health – as only healthy children will be accepted) fly to Germany on behalf of the DKF on 27 April 1948. They aim to locate healthy White, German, Protestant orphans aged between 3 and 8 years old. They target the Schleswig-Holstein region, for two reasons – firstly it is in the most Northern German state bordering Denmark and would offer the most ‘Aryan’ and ‘Nordic’ orphans, secondly it is occupied by the British and has 1.2 million displaced refugees. Botha hopes to gain sympathy from the British for his ambitious plan and alleviate the humanitarian aid pressure on them. From 22 May 1948, Botha broadly advertised in the local papers looking for children who could emigrate to South Africa, with the prerequisite that they should be German, white and Protestant39.

Shortly after the arrival of the DKF in Germany, there is step-change in South African governance when the National Party, against the odds, wins the General Election on 26 May 1948. With any impediments of the Smuts government out the way Botha is confident of his plan and the support of the local Schleswig-Holstein authorities. However his plan hits its first real impediment when the Schleswig-Holstein government meets on 30 May 1948 and rejects the adoption of children for collective emigration. This forces Botha, as a last ditch effort, to approach the Interior Minister of Schleswig-Holstein, Wilhelm Käber, Käber is known to have “pro-Boer” sentiments and influenced by the pre-war “Ohm Krüger” (Uncle Kruger) sentiment and propaganda. Käber takes sympathy and despite reservations and criticisms agrees to a limited collective emigration. This is later ratified by his government on the proviso it is limited to orphans only40.

The DKF hits another significant setback when they start their adoption campaign. Most children don’t meet the profile of ‘orphan’ and many have existing parents which due to war are displaced or traumatised and have offered their children to homes. However a greater problem is found on the ‘health’ front, Dr. Vera Bührmann rejects a significant number of children due to malnutrition, mental trauma or tuberculosis, so much so that Botha reports to the board of the DKF that numbers are insufficient and the age limits and orphan status need to change to throw the net wider.

In the end the age criteria is changed from 2 to 13 years old and Botha and Bührmann are able to only identify 87 children, many of which are not really orphans and almost all of them still have families. However, a general apathy sets in and nobody in the German authority gives the necessary oversight to control this. The initial 83 children are packed off to South Africa on 20 August 1948 via the United Kingdom, boarding a Union Castle line to Cape Town (the other 4 would join later)41 .

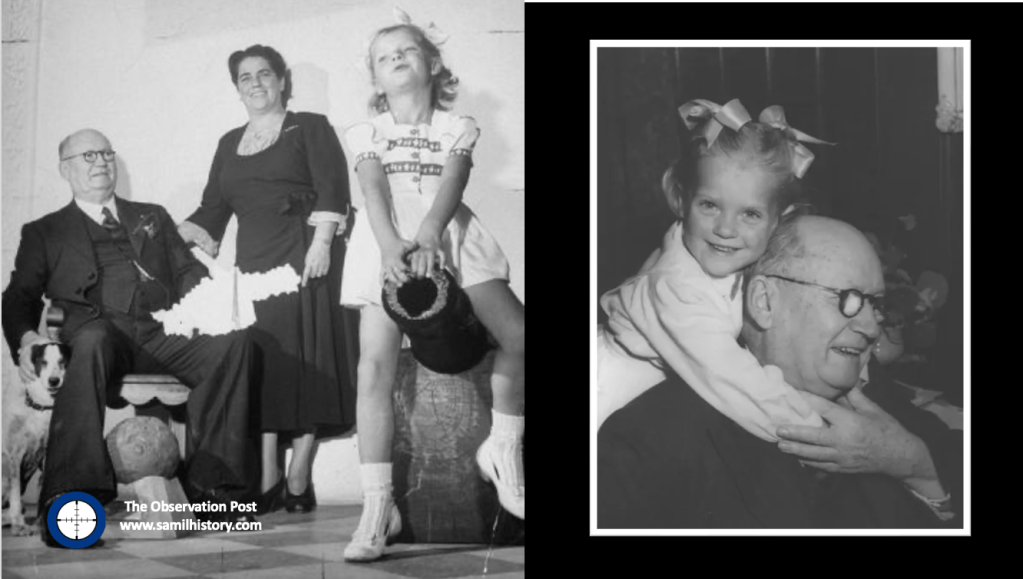

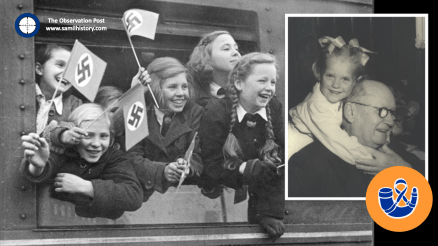

Back home in South Africa, the Afrikaner press carried advertisements for volunteer parents. Only Afrikaans speakers and members of the Dutch Reformed Church were eligible to adopt a child. 450 parent couples expressed interest in adopting a child. With limited numbers, preference was given to families regarded as ‘Afrikaner elite’. The children arrived in Cape Town on 8 September 1948 to a media scrum. They were taken to the German Club to meet more press and prospective parents. The older children would describe the scene as a “cattle market”.42

Some good, some mixed results

Prime Minister D.F. Malan, wrote to the The German Children’s Fund to express his interest in adopting a child. It went without saying that the application of a person of his stature would be successful, it would create all the necessary hype, and he and his wife Maria would have first choice from the new arrivals in Cape Town. However the Malan’s only want a little girl. Maria Malan selects four-year-old Hermine from Deezbüll near Husum and gives her a new name: Marietjie. To Maria, it was a “spiritual birth” to the new child – Marietjie means “little Maria” however “Marietjie” also has alongside her, her inseparable two-year-old brother Gerhard, so as siblings they are dutifully torn apart43.

It takes approximately a week until all the children are distributed to their new parents. Some travelled by train to Pretoria, and are welcomed by the Kappiekommando – a woman’s brigade strictly of ‘Boer’ heritage (known for wearing the traditional Dutch ‘kappie’ head-dress). Most of the adoptive parents were well to do Afrikaner nationalists who had served in the higher structures of the Broederbond, the National Party, the Ossewabrandwag, New Order and the Grey-shirts. It is no surprise really that many of these children went on to receive privileged lifestyles and educations. Some making important contributions.

Marietjie Malan, would soon wrap the Prime Minister around her little finger. Members of the press, accustomed to running into a brick wall when they attempted to interview Malan, witnessed Malan’s stern features softening when Marietjie appeared. She was the only person who was able to circumvent Maria’s strict rule that Malan was generally not to be disturbed. Yet, while Malan strolled and played with his new daughter the violent outcome of Malan’s intense race politics was beginning to play out in South Africa.

Werner Nel, one of the more famous of the children, became an internationally renowned operatic baritone, and later a professor of music at Potchefstroom University. He even went on to receive the South African Academy of Science and Art award, the Huberte Rupert Prize for classical music. Other predominant children from this program included Professor Eike de Lange, Professor Siegfried Petrick (Veterinary Science) and Professor Werner van der Merwe (History).

There were some mixed results, some of the orphans even had a tough time. Future pig farmer Herbert Leenen found himself used as no more than a farm labourer by his new family and eventually broke ties with his new “parents”.

Some very bad results!

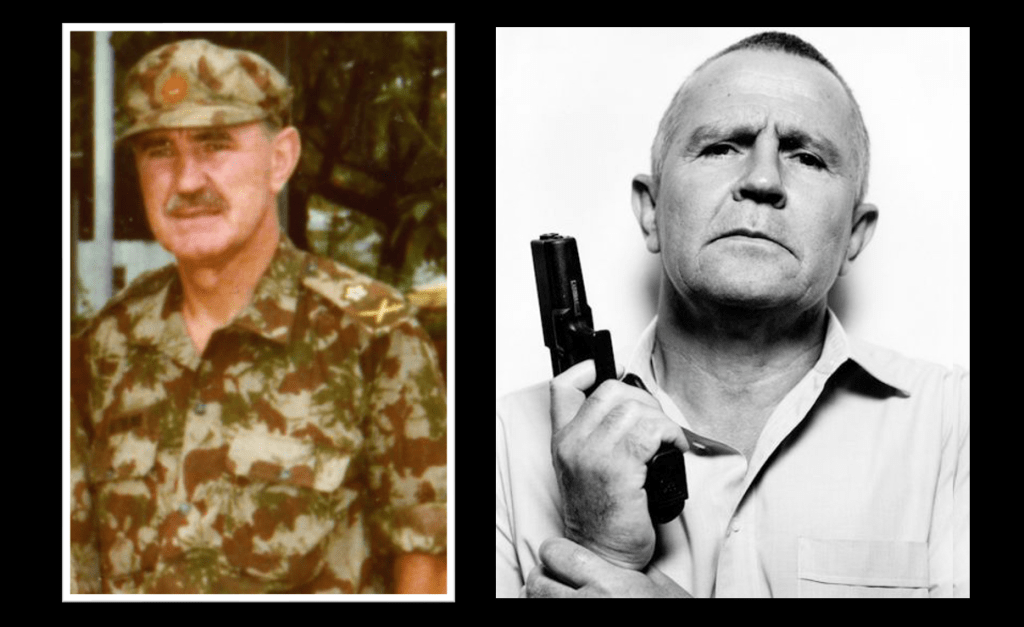

However, here were also some “bad eggs” – here, the issue points to nurture and not nature. One particular adopted child is standout, as not only does he effectively assimilate into his new environment, he brings to it just about everything the Nazi regime stands for and is feared for. Whilst in Germany, when Schalk Botha arranged for the lifting of the age requirement of the DKF to 13 years old – a problem would arise with pre-nurtured and pre-conditioned children exposed to Nazism. Aware of this, Dr. Vera Bührmann took pity on one such Prussian teenager – 13 year old Lothar Paul Tietz, whose brother and sister had made the cut and he was ‘on the edge’ of the spectrum. Coming from a committed Nazi family how their parents were killed is not known, what is known is that towards the end of the war the Tietz siblings were moved to an orphanage in Elbing, here Bührmann was able to interview them, Lothar Tietz later recalled in a SABC TV interview that he pleaded with “Tanti Vera” to keep the three of them together, an impressive boy, Lothar Teitz was tall and polite – he had received five years of National Socialist education and had been exposed to the Hitler Youth44.

As the oldest of all the 83 children allocated to the initial voyage to Cape Town, Lothar Teitz took the role of ‘head boy’ in organising the children. Once in South Africa the Tietz children were separated. Lothar Tietz was handpicked for adoption by the Chairman of the Pretoria branch of the DKF, Dr. JC Neethling. Dr. Neethling had himself been interned by the Smuts government during WW2 for pro-Nazi sedition, he had been a ‘Grey-shirt’ and later a ‘Black-shirt’. Eager to assimilate into his new culture and desperate for a sense of “order”, Lothar adopted the Neethling surname, cut ties with Germany and was to quote him “pleased to adopt my new fatherland “45.

Lothar Neethling did his utmost to ingratiate himself with his hosts by becoming a better Afrikaner than his classmates – excelling in rugby, school work, and absorbing every nuance of Afrikaner culture. The very astute and bright Lothar Neethling would grow up to become a General in the South African Police Force, and eventually Chief Deputy Commissioner of the Police (scientific and technical services) during the Apartheid era.

He also became a respected scientist in his own right, earning two doctorates in forensics – one from the University of California – and was honoured by several prestigious international scientific associations. He became a member of the Afrikaans Academy of Arts and Science and his scientific work earned him awards including a golden award from AAAS and a medal from the Taiwanese government. In 1971, Neethling founded The South African Police’s forensic unit. His work in the unit earned him seven SAP awards and three years later he was appointed Chief Deputy Commissioner.

However some serious clouds were brewing over General Lothar Neethling. In November 1989 Captain Dirk Coetzee, the former commander of the “Vlakplaas” South African Police “death squad”, pulled the plug on “hit squads” with a newspaper scoop. Among his allegations was that Neethling used the police forensic laboratories he controlled to supply him with “knock-out drops” for the murder of anti-Apartheid activists. Coetzee alleged that he would collect the poison – known to him as “Lothar’s potion”, from Neethling’s home or from his laboratory, and administer to it to suspects and kill them. It would eventually earn Lothar Neethling the monstrous title of South Africa’s “Dr. Mengele”46.

The Truth and Reconciliation commission also established the role played by Neethling’s laboratories in the production and supply of poisons to assassinate anti-apartheid activists, and also revealed Lothar Neethling was the number-two man in Dr. Wouter Basson’s biological and chemical warfare programme. Numerous court cases followed finding Neethling’s testimony unreliable or inconclusive. In a hail of controversy, charges and allegations, Lothar Neethling died of lung cancer in Pretoria on 11 July 2005, aged 69. Whether the allegations were founded or not, his legacy and that of the DKF’s adoption program would be forever tarnished. Whether earned or not, his legacy as South Africa’s “Dr. Mengele” has now entered into the Apartheid lexicon47.

In Conclusion

There has been a long standing debate in academic circles, and it evolves around Apartheid’s origins and historiography. Two sides emerged from the debate, both agree that the origin of Apartheid is slavery in the Dutch Cape Colony, however after that the two arguments go separate ways.

One group points to the Voortrekker’s Puritan religious standpoint which brought the idea of “separate worship” for Blacks and Whites into Dutch Reformed Church (NGK) policy. The epicentre is the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) NGK Synod in 1857 and subsequent Synods and NGK Dominees come to define Apartheid along the lines of Jim Crow Laws, Darwinist Eugenics and Southern American State Segregation policies. This group defines Apartheid as a derivative of American Segregation along ecclesiastical lines.

The other group points to the advent of National Socialism (Nazism) in the mid 1930’s as the key political driver of Apartheid’s origin, and they name the National Party’s ‘Think Tank’ Professors and academics who are all enamoured and besotted with Nazi Germany, anti-Semitism, Nuremberg Race Laws and Weimar Eugenics as the chief proponents of it. This group would define Apartheid as a derivative of National Socialism along party political and ideological lines.

Stepping into the fray to sort the argument out once and for all in 2003 was the heavy-weight Afrikaner historian – Professor Hermann Giliomee. He concluded in his work ‘the making of Apartheid’ that the essence and origin of Apartheid lay along the NGK’s ecclesiastical lines and had nothing to with Nazism. He cites a famous speech by Dr. DF Malan in 1947, and taking it at face value he formats it as the crux of his argument, it’s a speech where Malan declares that it is not the state that took the lead with Apartheid, it was the NGK Church who led it and the NGK Synod in 1857 marks the start of it48.

What Professor Giliomee loses sight of by quoting DF Malan, is it is this very man who is front a centre in a very Weimar Eugenic based Aryan adoption program to boost the bloodline of white Afrikaners with Nazi German Herrenvolk blood and to advance an Völkisch ideology in South Africa. Malan not only opens the way for this ideology and thinking by the “Germanophiles” and wartime pro-Nazi leaders in his party, he even adopts one of the children. The DKF is not only inspired by National Socialist dogma, it is a vert practical and realistic application of it in South Africa.

Giliomee also loses sight of the fact that Malan makes this declaration in 1947, after the end of the war in 1945 and the exposure of Nazism and its ideological connection to the holocaust, and by deflecting to the NGK church (to which he is pre-disposed to do as a Dominee anyway) he is gaslighting for the plethora of “Germanophiles” who have been advocating National Socialism in all the various Afrikaner Nationalist cultural, media and political structures and who have all subsequently been warmly welcomed into the HNP’s fold and its leadership caucus. Especially after their 1948 election win and the merger with the Afrikaner Party to reconstitute the HNP as the “National Party” (NP).

To be fair to Giliomee, what he does not have sight of in 2003 is all the recently uncovered archive files and materials found 20 years later. Documents on the Ossewabrandwag pointing to Nazi collusion – files, court records, letters, memos and confessions from South African Nazi renegades within Afrikaner nationalism captured and interrogated in the Rein Commission and published in the Barrett Commission findings after the war – files which were, until recently, regarded as either missing or embargoed. Even the recent findings and academic works on the Nazi German propaganda program in South Africa makes for an eye-opening historiography of Apartheid.

Previously embargoed or missing files – primary source material – have now finally put the nail into the ecclesiastical argument as the sole origin and development of Apartheid and we can now finally conclude that not only was Apartheid ‘invented’ by the NGK, it was subsequently infused with National Socialism – and although not Nazism in its purest form it is indeed a derivative of Nazism. The German Herrenvolk blood for the Afrikaner Volk adoption program run by the DKF after the war is just one such practical example which underscores this conclusion.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References:

- Wener van der Merwe. Herrenvolk Bloed vir die Afrikaner: Veertig Jaar Duitse wees kinders (1948-1988) UNISA on line journal.

- Wener van der Merwe, Vir ‘n ‘Blanke Volk’: Die Verhaal van die Duitse Weeskinders van 1948 (Johannesburg: Perskor-Uitgewery, 1988)

- Jonathan Hyslop. White Working Class Women and the Invention of Aparthied: ‘Purified’ Afrikaner Agitation for Legislation against Mixed Marriages 1934-1939. Journal of African History Vol 36, No 1 (1995) published by Cambridge University Press

- Andries M Fokkens. Afrikaner unrest within South Africa during the Second World War and measures taken to suppress it. Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Journal 37(2) 2012.

- Hermann Giliomee. The Making of the Apartheid Plan, 1929-1948. Journal of Southern African Studies , Vol. 29, No. 2 (2003). Publisher, Taylor & Francis.

- Furlong, Patrick J. Pro-Nazi Subversion in South Africa, 1939-1941. 1988. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 16(1)

- Maritz, Manie ‘My Lewe en Strewe’ Pretoria 1939

- Karl Dahmen. Wer hat Angst vor dem schwarzen Land? Die kollektive Adoption norddeutscher Kinder nach Südafrika (Who’s afraid of the black country? The collective adoption of north German children to South Africa), Demokratische Geschichte / Gesellschaft für Politik und Bildung Schleswig-Holstein e.V, 2010.

- Gavin Evans. The man with the deadly past. Mail and Guardian, 28 August 1998. Interview with General Lothar Neethling

- Max Du Preez. SA’s own bemedalled Dr Mengele is dead. IOL, 13 July 2005.

- Chris Ash. Kruger’s War – the truth behind the myths of the Boer War. Durban: 30 degrees South Publishers, 2017.

- Bunting, Brian. The Rise of the South African Reich. Penguin Books. 1964

- Harrison, David. The White Tribe of Africa: South Africa in Perspective. Macmillian Publishers. 1981

- Kleynhans, Evert – Hitler’s Spies, Secret agents and the intelligence war in South Africa, 1939 to 1945. Jonathan Ball. 2021

- Milton, Shain. A Perfect Storm – Antisemitism in South Africa 1930-1948. Jonathan Ball. 2015

- Mouton, F.A. The Opportunist: The Political Life of Oswald Pirow, 1915-1959. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis. 2022

- Shirer, William. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. 1974 edition.

- Strydom, Hans. For Volk and Führer: Robey Leibbrandt & Operation Weissdorn. Jonathan Ball. 1982

- Visser, George C. OB: Traitors or Patriots. Macmillian. 1976

- Bloomberg, Charles. Christian Nationalism and the Rise of the Afrikaner Broederbond in South Africa, 1918 to 1948. Indiana University Press. 1989

- Bouwer, Werner. National Socialism and Nazism in South Africa: The case of L.T. Weichardt and his Greyshirt movements, 1933-1946

- Fokkens, A.M. Afrikaner unrest within South Africa during the Second World War and the measures taken to supress it. Journal for Contemporary History 37/2. 2012

- Furlong, Patrick J. Allies at War? Britain and the Southern African Front in the Second World War. South African Historical Journal 54/1. 2009

- Furlong Patrick Jonathan – National Socialism, the National Party and the radical right in South Africa, 1933-1948 (D.Phil. Thesis, University of California, 1990

- Furlong, Patrick J. Pro-Nazi Subversion in South Africa, 1939-1941. 1988. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 16(1)

- Grundlingh, Albert. ‘The King’s Afrikaners? Enlistment and Ethnic Identity in the Union of South Africa’s Defence Force during the Second World War 1939-45’. Journal of African History 40 (1999).

- Marx, Christoph. Ox wagon Sentinel: Radical Afrikaner Nationalism and the History of the Ossewabrandwag. South African University Press. 2008

- Monama, Frankie. Wartime Propaganda In the Union of South Africa, 1939 – 1945. Dissertation, University of Stellenbosch. 2014

- Mouton, F.A. 2018 ‘Beyond the Pale’ Oswald Pirow, Sir Oswald Mosley, the ‘enemies of the Soviet Union’ and Apartheid 1948 – 1959. UNISA, Journal for Contemporary History 2018

- Scher, David M. Echoes of David Irving – The Greyshirt Trial of 1934.

- Werner, Bouwer. National Socialism and Nazism in South Africa: The case of L.T. Weichardt and his Greyshirt movements, 1933-1946

Footnotes

- van der Merwe, Herrenvolk Bloed vir die Afrikaner, Page 78 ↩︎

- Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich, 57 ↩︎

- FA Mouton, ‘Beyond the Pale’ Oswald Pirow, Sir Oswald Mosley, the ‘enemies of the Soviet Union’ and Apartheid 1948 – 1959, Journal for Contemporary History, 43, 2 (2018), 18. ↩︎

- FL Monama, Wartime Propaganda in the Union of South Africa, 1939 – 1945 (Dissertation for the degree of history, University of Stellenbosch. Stellenbosch, 2014), 62. ↩︎

- M Shain, ‘A Perfect Storm’, Antisemitism in South Africa 1930-1948, (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2015) , 55–58. ↩︎

- W Bouwer, National Socialism and Nazism in South Africa: The case of L.T. Weichardt and his Greyshirt movements, 1933-1946. (MA Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein 2021), 18. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 84 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 76. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 82. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 230. ↩︎

- Harrison, The White Tribe of Africa, 103 – 106. ↩︎

- DP Olivier, A special kind of colonist: An analytical and historical study of the Ossewa-Brandwag as an anti-colonial resistance movement (thesis, University of the North West, Potchefstroom 2021), ↩︎

- Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich, 84 ↩︎

- Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich, 92 – 93 ↩︎

- EP Kleynhans, Hitler’s Spies, Secret agents and the intelligence war in South Africa, 1939 to 1945. (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2021), 199. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 238 ↩︎

- J Hyslop. White Working Class Women and the Invention of Aparthied: ‘Purified’ Afrikaner Agitation for Legislation against Mixed Marriages 1934-1939, 76 ↩︎

- H Giliomee. The Making of the Apartheid Plan, 1929-1948. Journal of Southern African Studies , Vol. 29, No. 2 (2003), 382 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm,131 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm,134 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm,132 – 133 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm,133 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 143-149 ↩︎

- Rein Commission. Unpublished ↩︎

- Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich, 85. ↩︎

- AM Fokkens. Afrikaner unrest within South Africa during the Second World War and measures taken to suppress it. Journal 37, No. 2 (2012), 142 ↩︎

- AM Fokkens. Afrikaner unrest within South Africa during the Second World War and measures taken to suppress it. Journal 37, No. 2 (2012), 142 ↩︎

- DODA: DC 3841, file DF/1887, proclamation 44 of 1941 ↩︎

- AM Fokkens. Afrikaner unrest within South Africa during the Second World War and measures taken to suppress it. Journal 37, No. 2 (2012), 135 ↩︎

- AM Fokkens. Afrikaner unrest within South Africa during the Second World War and measures taken to suppress it. Journal 37, No. 2 (2012), 129 ↩︎

- PJ Furlong. Pro-Nazi Subversion in South Africa, 1939-1941. 1988. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 16(1) ↩︎

- PJ Furlong. Pro-Nazi Subversion in South Africa, 1939-1941. 1988. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 16(1) ↩︎

- Werner van der Merwe. Herrenvolk Bloed vir die Afrikaner: Veertig Jaar Duitse wees kinders (1948-1988) UNISA on line journal, 78 ↩︎

- C Ash, Krugers War, the phrase initiated the ZAR official Rev. SJ Du Toit after the London convention in 1884 ‘The South African Flag shall yet wave from Table Bay to the Zambezi, be that end accomplished by blood or by ink. If blood it is to be, we shall not lack men to spill it.’ is repeated by ZAR politicians and Afrikaner bondsmen up to and including Jan Smuts’ final statement in Oct 1899 prior to the start The South African War. ↩︎

- Maritz, ‘My Lewe en Strewe’, 269 ↩︎

- W van der Merwe. Herrenvolk Bloed vir die Afrikaner, 81 ↩︎

- W van der Merwe. Herrenvolk Bloed vir die Afrikaner, 85 ↩︎

- W van der Merwe. Herrenvolk Bloed vir die Afrikaner, 78 ↩︎

- K Dahmen. Wer hat Angst vor dem schwarzen Land?, 114 – 115 ↩︎

- K Dahmen. Wer hat Angst vor dem schwarzen Land?,115 ↩︎

- K Dahmen. Wer hat Angst vor dem schwarzen Land?,119 ↩︎

- K Dahmen. Wer hat Angst vor dem schwarzen Land?,119 ↩︎

- K Dahmen. Wer hat Angst vor dem schwarzen Land?,122 ↩︎

- Evans. The man with the deadly past. M&G 1998. ↩︎

- Evans. The man with the deadly past. M&G 1998 ↩︎

- Du Preez. SA’s own bemedalled Dr Mengele is dead. ↩︎

- Du Preez. SA’s own bemedalled Dr Mengele is dead. ↩︎

- H Giliomee. The Making of the Apartheid Plan, 383. ↩︎

The is a very big separation between race politics in the Smuts epoch and the Apartheid epoch. Race politics existed in South Africa during the Smuts era, of that there is no doubt. However Smuts was addressing it and political resistance on a really ‘mass’ basis from from these communities did not really exist at the time. Smuts and his politics are complex, he initiated violent counter action to any dissonance by striking miners or Afrikaner rebellions (whether Black or White, it mattered not a jot to him) but more often than not used dialogue, and a lot can be said to the fact that the ANC in fact supported Smuts’ decision to take the country to war in 1939/40.

The is a very big separation between race politics in the Smuts epoch and the Apartheid epoch. Race politics existed in South Africa during the Smuts era, of that there is no doubt. However Smuts was addressing it and political resistance on a really ‘mass’ basis from from these communities did not really exist at the time. Smuts and his politics are complex, he initiated violent counter action to any dissonance by striking miners or Afrikaner rebellions (whether Black or White, it mattered not a jot to him) but more often than not used dialogue, and a lot can be said to the fact that the ANC in fact supported Smuts’ decision to take the country to war in 1939/40.