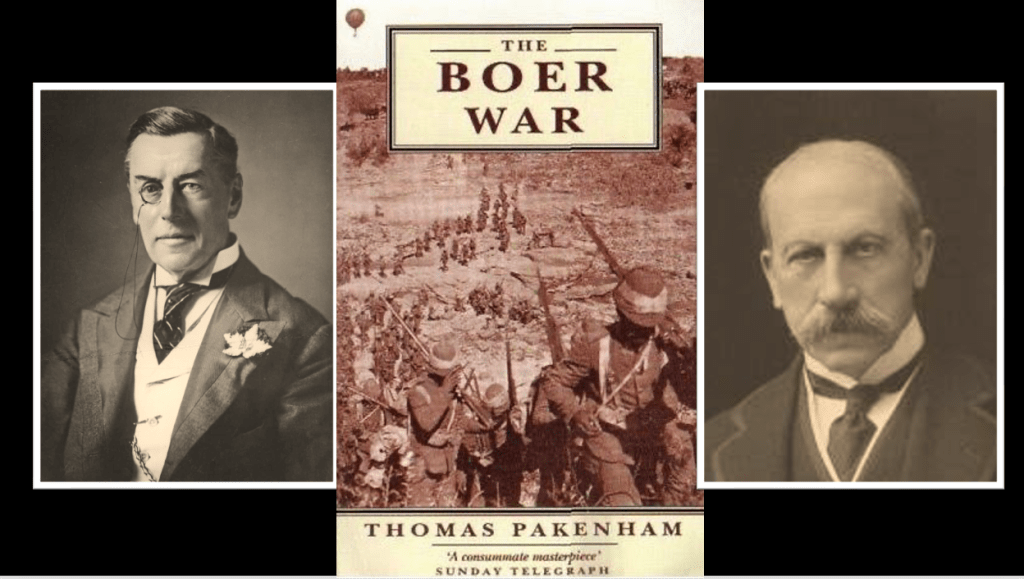

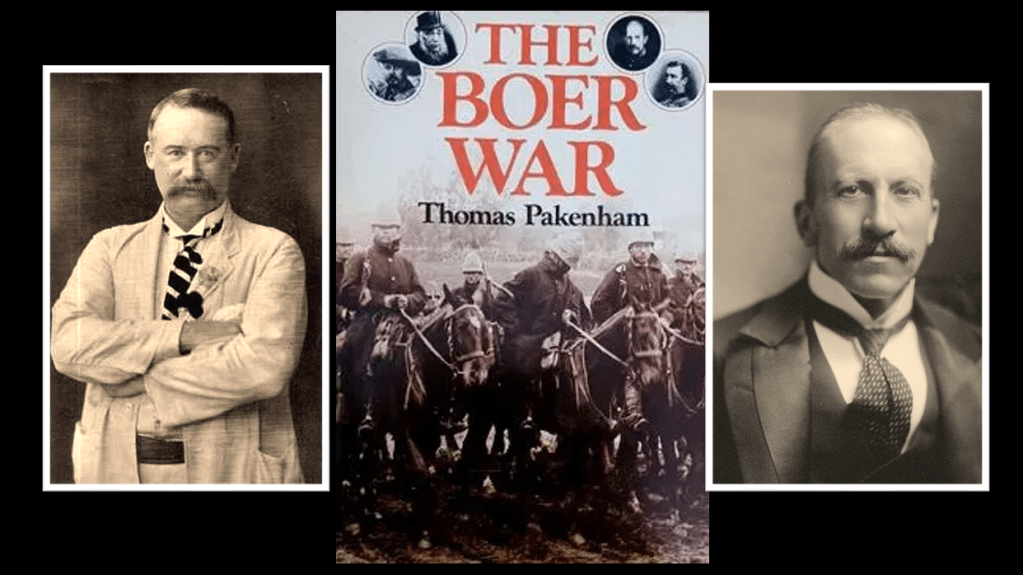

I’ve just finished reading Thomas Pakenham’s ‘The Boer War’ … AGAIN, this is my 7th time. Pakenham was the first book I read on the Boer War in the early 80’s and it has been my go-to, it’s easy and it reads like a novel, section 1 sets up a ‘gold-bug’ conspiracy complete with political intrigue, and it becomes a page turner after that.

As I’ve matured as a history lover and commentator, and even lately mapping out my own historical papers for academic scrutiny, I’ve become more astute on challenging material. I’ve learned that the closer you are to archive material and source documents the better – and this is where references and sources become critical to history books.

Doing ‘history’ on a 19th Century topic in the 21st Century is interesting, as in between there are all the 20th Century historians – and sometimes what they have penned as ‘truism’ seems to hold and is simply taken by the 21st Century historian chaps as a grounded fact and then they expounded and expanded on it without really challenging its origins, and whole historical misunderstandings are easily created.

The interesting bit is when you hit an archive and discover the 20th Century historian has not grounded the fact properly, and what has come after him is pure hyperbole – and that unfortunately is the case with Pakenham … and here’s how.

The Boer War and Race

One of the most relevant issues and topics when looking at the South African War 1899 -1902 a.k.a. Boer War 2, in the 21st Century is the topic of ‘race’ and the related topics of ‘franchise’ and ’emancipation’. To really understand how ‘race’ is viewed and acted upon in the war within the context of its time and then what role subsequent historians and commentators during the Apartheid period took to dismiss it from the narrative or side-line it as irrelevant in what has been essentially pitched as ‘white man’s war’ between two ‘white’ antagonists – the black man is a but a part player merely along for the ride.

Even in ‘white’ communities in modern South Africa today, the ‘Boer War’ is a war from which the ‘Black’ man is excluded at the beginning and excluded at the end. They sincerely believe that. So much so, that academic attempts to re-brand the war on its official name “The South African War (1899-1902)” to incorporate the full scope and all the belligerents (black and white – British, Boer, Tswana, Swazi etc.) – still goes completely unnoticed in ‘white’ Afrikaans communities especially – and they still call it the “2nd War for Independence” (whose independence was at stake is anyone’s guess) or the “Anglo-Boer War” (Brits and Boers only thanks).

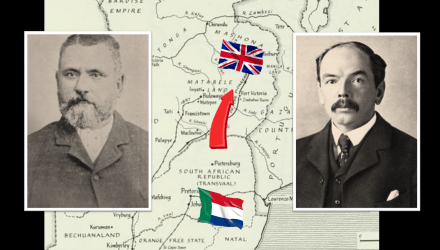

This perception starts to really take shape with historians writing on the Boer War during Apartheid, and here Pakenham in section one of his ’The Boer War’ book sets it up perfectly. From the get-go, as the good travel writer and journalist he is (he was not a qualified historian and the “The Boer War” by T Pakenham is his first real attempt at a history book), Pakenham decides on who is a villain and who is a hero, like any good novel – very important if you’re going to set up a ‘page-turner’ and reinvigorate a tired old boring subject with some flare and creative license.

Creating a Villain

Been an Irish Republican himself, Pakenham is almost predisposed to vilifying British Imperialists. To build Alfred Milner as his villain, Pakenham uses two key meetings – one meeting with Joseph Chamberlain on 22nd November 1898 where Milner gets ‘his orders’ so to speak and one meeting with Percy Fitzpatrick from the Reform Committee (the Uitlanders) on the 31st March 1899 where he gives the ‘Uitlanders’ some advice to how to advance their cause and declares his own commitment to their cause. Seems legit right? Let’s focus on each and see how Pakenham ‘interpreted’ these meetings.

On the meeting in London with Chamberlain – Milner outlines that a “crisis” is developing over the Uitlander franchise as Kruger is simply unbending and is showing no signs of compromising. Chamberlain is of the opinion that “time” will resolve the crisis, leave Kruger to his unreasonable demands and simple democracy, civil pressure and process will see in inevitable change (in other words give Kruger enough rope and he’ll eventually hang himself). To quote, Chamberlain tells Milner to do two things 1. That a peaceful settlement is the only settlement the “British Public” i.e. Parliament will accept and 2. Keep things moving “forrarder” in South Africa (old English – ‘Forrarder’ means ‘forward’).

Milner also agrees with Chamberlain that he will “screw” Kruger – now before you jump to a 21st Century conclusion, “screw” in Victorian times comes from word used to describe a prison official and the ‘screw’ was a pressure machine prisoners aimlessly turned as a punitive measure – to ‘screw’ means to “increase pressure” on Kruger politically (and not to “screw” him out of his country as would be a ‘literal’ 21st century translation and one that it is so often misquoted by Afrikaner Boer War enthusiasts).

Those are Milner’s orders – from his boss. Straightforward enough.

In a modern context Chamberlain is telling his civil servant in the colonial office in South Africa to conclude an acceptable peace without using violence and keep up the good work, keep going and keep pushing.

But this is not Pakenham’s’ take on the meeting at all, Pakenham sets up the meeting as Milner intentions on artificially ‘working up a crises’ to urge Chamberlain to agree a pathway to war – that no such ‘pathway’ is even mentioned nor is one discussed matter not a jot to Pakenham. Thomas Pakenham then uses the phase of “moving things ‘forrander’ locally” and declares it a “hint” to Milner to continue with an aggressive ‘forward’ policy to annex the Transvaal Republic. That there is absolutely nothing backing Pakenham up in his assertion that Chamberlain is “hinting” to Milner to continue creating conditions for a war and the annexation of a Republic does not deter Pakenham at all – with no proof whatsoever he keeps up his vilification of Milner (and Chamberlain). It gets worse.

The meeting between Percy Fitzpatrick and Alfred Milner is Pakenham’s next focus. So, what happens here? – Fitzpatrick as a Reform Committee leader (and Uitlander in the Transvaal) meets with Milner to put the case of the Uitlanders, to outline their beef with Kruger as a crisis and put their franchise issue front forward.

Milner sympathises with Fitzpatrick and says his “heart and soul” are with the miners and their predicament. He indicates to Fitzpatrick that their case is not strong enough with the British public, and this is borne out by Parliament (and by default Chamberlain) who are unmoved – he suggests the next step is for the Uitlanders to strengthen their case to the ‘British Public” is a concerted focus on British “media” (the very partisan British press) – he however distances himself personally from involvement in this media campaign and indicates the Uitlanders have to go it alone (as he does not want to be seen as partisan and he’s toeing the line his ‘boss’ Chamberlain is demanding of him).

That’s it – in modern context, he sympathises with their cause, and he suggests they tighten up their PR and do a media blitz to strengthen their case, only he cannot be seen to be partisan to such a media campaign – Straightforward enough.

But that’s not Pakenham’s take, instead Pakenham sees this as collusion, purposefully building a crisis for the purposes of strengthening a case for war. He concludes that Milner’s avoiding of the proposed media campaign as duplicitous behaviour – covering his tracks as he’s breaking with his Boss’ instructions and fanning a war, and Pakenham does this again with absolutely no grounded fact whatsoever. It gets even worse.

Pakenham concludes all this with, and I’ll quote Pakenham directly.

“His (Milner’s) plan was to annex the Transvaal. He would rule it as a crown colony much as his old chief, Cromer, ruled Egypt”.

Pakenham goes on and states

“these were the dreams of Milner’s life and he saw no reason to abandon them because of one obstinate (and obsolete) old man in South Africa (editor – implying Kruger). But how to prevent Chamberlain “wobbling” and ruining everything by compromise? A delicate plan, whose object had to be kept as secret from Chamberlain as from Kruger, was taking shape in Milner’s mind.”

Wow! I mean … wow … a plan for annexation, a secret conspiracy, dreams of grandeur – a Napoleon in the guise of a British bureaucrat and who knew? …Where did Pakenham get all this information from? There must be a source, a reference of some kind, Milner must have betrayed his thoughts to a friend in a letter or similar, he’s drafted an annexation plan surely … and luckily there is a reference, Pakenham’s given it all a notation – number “25”.

Now I want to see this – it’s the entire crux of Pakenham’s argument, it’s the moment of truth, so over to No. 25 under Chapter 6 and it reads … “The evidence that Milner wanted a war is circumstantial.” Huh! … say what! There is no evidence – it’s all circumstantial – and this ‘truth’ is hidden in a notation at the back of the book! What’s going on?

Telling Porkies

In London cockney rhyming slang if you “tell a pork pie” it’s a “lie”. Telling ‘Porkies’ is to shield or be ‘sparing’ with the truth. One clear way of telling a porkie is to tell a ‘half-truth’ its sounds legit enough and has enough gravitas on which you can base an entire argument.

When it comes to Pakenham and ‘The Boer War’ on the issue of race and the British franchise demands outside of the ‘white’ uitlander issue i.e. the Coloured Franchise and the recognition of the rights of an urbanising Black African population drawn to mines and industry for labour – this bit of purposeful manipulation becomes masterful – as in one stroke Pakenham paints Milner as a rabid racist and he relegates the entire ‘Coloured’ franchise issue to a secondary status, citing Britain’s lip service to it because in his view deep down they are as racist and segregationist as the Boers – and he uses Milner to ‘deflect’ this rather thorny subject away from the ZAR Republic’s very racist ‘Grondwet’ and its institutionalised racism as reflected in Articles 31 and 32 (applicable to ‘white’ “non-Boers” and “coloured”, “Indians” and “blacks”) of the ZAR constitution.

What this does is relegate this issue of race to a ‘secondary’ status and builds the war as a white only affair for white rights. It goes against the another ‘narrative’ the modern black historians and academics point out – the ‘winds of war’ actually starts in earnest when Edmund Fraser meets Jan Smuts on the 23rd December 1898 and he warns the Republic that their treatment of their ‘Blacks’ is reaching unacceptable levels, he warns Smuts that issues like universal franchise and rights are the type of things the British public like to get behind because they are concepts the average Briton understands – and these easily understood equity and franchise concepts – like slavery – are issues the British government tends to go into a legitimate and justified war over.

This meeting leaves Smuts utterly gobsmacked and under the impression that the coming war is inevitable … it’s not just about the ‘white’ miners and their rights after all … it’s much bigger than that and the British are not going to stop at insisting on the 5 year franchise for the ‘whites’ only, next is the issue of Black rights. The British also don’t let go of this – throughout the war the ‘Coloured franchise’ and ‘Black’ protectorate and recognition issues are front and forward – it’s a ‘term’ for peace when the first peace negotiations are opened up with Louis Botha in February 1901 in Middleburg and it’s still a ‘term’ for peace when the Vereeniging Peace proposals are put forward in May 1902 …. It is Smuts’ skill as a lawyer and negotiator that its ‘kicked into the long grass’ to be dealt with a ‘future and independent’ union (a move Milner very rightly and prophetically clocks as future problem).

It’s a key part of the Boer War as the Boers continue with an entire guerrilla phase with the absolute devastation to their family and farm constructs precisely because they absolutely refuse to change their ‘grondwet’ (constitution) on franchise – and especially the coloured franchise. This is NOT what the Apartheid era politicians want taught about the war, to them it’s a whites only affair, it’s a result of a long standing feud dating back to the Voortrekkers … the ‘black’ issue is incidental and the Brits are not that serious about it anyway.

To put this very critical ‘part of the Boer War .. the entire ‘Black’ part of the war on the rump and kick it into the long grass – and in so to fall in line with the Republican narrative (and Apartheid philosophy of Boer victimisation) we need the villain to give the ‘black’ issue the old heave-ho … and Pakenham turns to Milner, his warmongering “Cromer”, so here’s the quote he users – it’s from a letter Milner writes to a friend.

“You have only to sacrifice ‘the nigger’ and the game is easy”.

Wow, what a powerful and condemning quote – proof positive, the ‘Black’ man is the sacrificial lamb, nothing more – the British will happily deflect the black issue, they’re a pawn in their greater ‘game’ to annex the Transvaal, the British aren’t serious about the ‘black emancipation’ – it’s just a scapegoat – and Milner is a vile racist and bigot to boot!

Ah … small problem. It’s a half truth, in fact it’s a complete misquote – and by misquoting it Pakenham is setting up an entire preconceived bias, on purpose he is guiding historic opinion and creating fiction not fact – he’s telling porkies … here’s the quote in full and when you’re done reading it you’ll realise the injustice and the depth of the problem, as Pakenham purposefully leaves this bit out, he’s character assassinating and he’s guiding an preconceived agenda – here is Milner’s quote in full:

“If I did not have some conscience about the treatment of blacks I personally could win over the Dutch in the Colony and indeed all the South African dominion without offending the English. You have only to sacrifice ‘the nigger’ and the game is easy. Any attempt to secure fair play for them makes the Dutch fractious and almost unmanageable”.

Hang on a tick, that quote is completely different … hold the horses … Milner is NOT a racist, he cares about the plight of Black South Africans, and he’s frustrated at the Republics treatment of them and their lack of resolve or plain reason to even open the subject of black emancipation and deal with it. The ‘sacrifice’ bit and even the ‘nigger’ bit is a throwaway line referring to simply leaving out the subject altogether when dealing with the Boers as it would make life easier, and it’s something (by his own consciousness) he is simply not prepared to do.

… so that’s a bit different, now you have to ask yourself – what is Pakenham trying to do why is he been deceptive – for what purpose?

Where Pakenham fails to peruse the ‘Black’ angle of the Boer War, the esteemed and renowned British historian Andrew Roberts FRSL FRHistS has a sharply different take to Pakenham’s argument and would fall back on Leo Amery and the entire black and white franchise argument in this statement of his:

“Although the Boer War has long been denounced by historians as the British Empire’s Vietnam, and characterised as being fought for gold and diamonds, and trumped up by greedy, jingoistic British politicians keen to bully the two small, brave South African republics, the truth was very different. Far from fighting for their own freedom, the Boers were really struggling for the right to oppress others, principally their black servant-slaves, but also the large non-Afrikaans white Uitlander (‘foreigner’) population of the Transvaal who worked their mines, paid 80% of the taxes, and yet had no vote. The American colonists had fought under James Otis’ cry that ‘Taxation without representation is tyranny’ in 1776, yet when Britain tried to apply that same rule to Britons in South Africa, she was accused of vicious interference’.”

Now, if we think this is all unsubstantiated character assassination so far, it gets worse again, Pakenham carries his now artificially grounded warmongering, scheming, conspiracist and racist ogre that is his Milner into the next chapters which he brands ‘Milner’s war’ and we start with the Bloemfontein conference with Kruger.

For Suzerainty Sakes

Most people have the impression that the Bloemfontein conference in June 1899 was all about Milner unbudging and arrogant and Kruger pleading and declaring all Britain wants is his country – greedy and after the gold, Pakenham highlighting Kruger’s tearful cry at the conclusion of Milner’s browbeating arrogance when the poor simple farmer stands up to leave and cries “it is our country you want” a statement which in actuality startled Krugers’ own negotiating team members like Smuts who saw it for what it was – melodrama, but not Pakenham – a whole chapter in his book is named after this statement of Kruger’s and he holds it up as proof positive of Milner’s intentions as a warmonger.

This perception of a callous British bureaucrat intent on war is carefully built by Pakenham as he very carefully omits ‘the British case’ and focuses primarily on ‘the Boer case’, and the proof is in the pudding … what if I said the whole franchise negotiation centred around the Transvaal’s Suzerainty status – and had nothing to do with ‘stealing’ the Transvaal’s gold. “Huh!”, the universal cry … what’s a Suzerainty? And here’s exactly the problem, the ‘British case’ is entirely misunderstood, and its largely thanks to Pakenham – historians prior to Pakenham, like Leo Amery extensively cover the complex issue of the Suzerainty – it’s a critical part of the Casus Belli … Packenham on the other hand merely gives it lip service and glances over it.

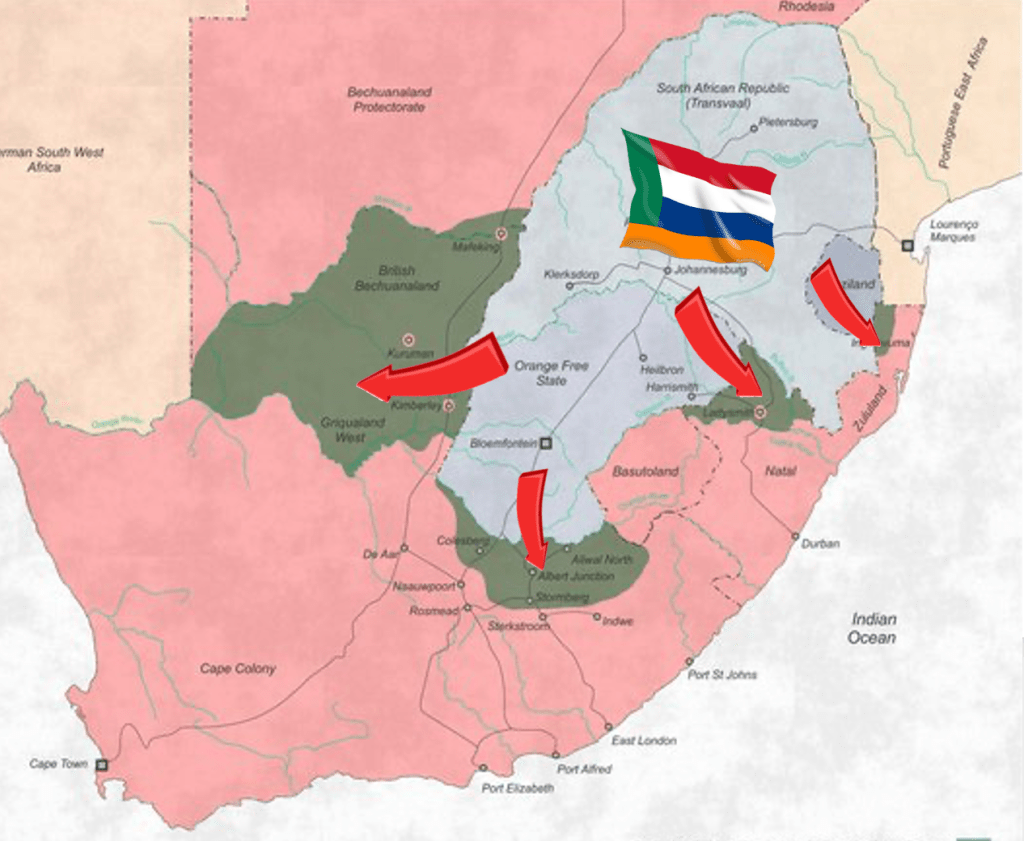

If you want to really understand the ‘road to war’ and the real underpinning issues which caused the war, you have to understand the Suzerainty, the ‘vassal state’ or ‘client state’ status of the Transvaal (Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek – ZAR) – as it was by no means, not in a month of Sunday’s, a “Sovereign” or a “fully independent” Republic. On the franchise issue, Britain was “meddling” in its own Suzerain and not in some independent state, something it regarded as perfectly legal in the spirit of the “Conventions” of 1881 and 1884.

Yup, sorry to burst the bubble on this one but the ZAR was never legally “fully independent” – lots of politicians on both sides gave it lip service, promises of respect for each other’s so called “independence”, but the hard truth is that legal treaties existed, The Pretoria Convention of 1881 and the London Convention of 1884 which allowed the ZAR no foreign policy whatsoever, they had to defer all of it to Britain – for all their foreign relations and even matters pertaining to trade and trading tariffs (affecting movement of “goods” and even labour) and even their borders (their expansion plans and claims to other territories and ‘old’ Republics like Natalia, Winburg and Stellaland were clipped)– the ZAR had no legal rights in external dealings with any other country other than the Orange Free State – neither foreign treaties or even foreign trade tariff deals could be struck legally without Britain’s consent – none whatsoever. The ZAR remained a British vassal state from the day it stopped being a British colony on the 23rd March 1881 to the date the ZAR “Raad’ and Kruger declared war on their Imperial Suzerain – Great Britain, on 11th Oct 1899 – that’s a fact (and a surprise to many I’m sure).

Now, you can start to see the complexity that was the backwards and forwards between Milner and Kruger. This is such a complex issue that I will be publishing an Observation Post on it called “For Suzerainty Sakes” in future, so readers have a better understanding of the causes of Boer War 2 (and Boer War 1 as the Suzerainty is a critical component of the 1st Boer War or Transvaal War 1880-1881). Churchill when captive and been shipped to Pretoria as a POW during Boer War 2, passed Majuba mountain and lamented in his historical account on the “disgraceful peace” which resulted from Boer War 1 and the true cause of Boer War 2 – and here he is referring the “Suzerainty” and not “gold” – and he is a commentator “from the time” – a first hand account and not a later commentator “of the time” like Pakenham – a second hand account.

Suffice to say Pakenham does not cover this issue of the ZAR’s true sovereignty in depth at all, the ‘British historians’ do, Pakenham doesn’t – choosing a rather concocted and completely unsubstantiated “conspiracy” of greedy capitalists in cohorts with Milner instead … and as a net result just about everyone in South Africa has no true understanding of what caused the war in the first place.

Long and Short to get a better understanding, Kruger opens his negotiations with the proposal that he will only consider a 5-year franchise for the “Uitlanders” if Britain drops all Suzerainty regulations governing the ZAR. Kruger lists 12 points he wants resolved before he will consider dropping the 15 year ‘franchise’ for Uitlanders to 5 years – which would bring it in line with all the bordering states’ franchise and labour movements regulated for ‘whites’ (this includes the Orange Free State, Natal, Rhodesia, Botswana and the Cape Colony).

In fact 9 of Kruger’s points are directly related to the ZAR’s Suzerainty restrictions. If the Suzerainty regulations are dropped this would mean the ZAR could change the power balance and threaten Britain’s paramountcy and power balance in the entire region – from the Zambezi all the way to Cape Point, enabling the ZAR to go into military treaties and trade alignments with other aspirational colonial powers like Imperial Germany thereby threatening Britain’s paramountcy in favour of a Boer one. That is a WHOLE lot more to it than mere “miners rights” and their greedy “gold” magnates on the reef as it put all of Britain’s colonies and the protectorates in the whole of southern Africa in a precarious position (3 full blown colonies and 3 colonial protectorates – 6 countries in all), and bottom line, the British (the Parliament and Chamberlain) and their ‘man’ on the ground – Milner, turn round to Kruger and simply say … “No”.

What follows is a four month long cat and mouse game with the Franchise period gradually dropping to 7 years with “conditions”‘ attached, its rejected by all (especially the Reform Committee) – thereafter desperate negotiations between Jan Smuts (for the ZAR) and W. Conyngham Greene (for Britain) continue and they settle on the final offer on 19th August 1899 – it is a 5 year franchise, the ZAR agree Milner’s original term and that there will be nothing “contrary to the Convention” (the ‘Convention is the 1884 version of the Suzerainty and by this it means the Suzerainty remains in place) – the agreement is outlined in a urgent telegram from Greene to Milner, everyone is relieved as war is now avoided, job done …. not yet … Francis Reitz, the ZAR State Secretary sends the ‘formal’ offer on the 21st August 1899 – in which he outlines the 5 year franchise – all good, on the PROVISO that Britain drops the Suzerainty completely, and he is very specific so as to clear up any ambiguity Smuts may have caused – not good. This is what Reitz writes:

The proposals of this Government (ZAR) regarding question of franchise and representation contained in that despatch must be regarded as expressly conditional on Her Majesty’s Government consenting to the points set forth in paragraph 5 of the despatch, viz. :

- (a) In future not to interfere in internal affairs of the South African Republic.

- (b) Not to insist further on its assertion of existence of suzerainty.

- (c) To agree to arbitration.

In Amery’s historical account, he notes at this stage it was “quite impossible for the British government to accept” Reitz’ final offer and that for the British they come to realise the ZAR has no intention to deal with the franchise issue – and this would lead subsequent historians like Paul Ludi to correctly conclude that all the subsequent Greene-Smuts talks were merely a delay tactic by Smuts to ready the two Afrikaner republics for their declaration of war against Britain.

As historians go, both Leopold Amery (then) and Professor Bill Nasson (now) and Andrew Roberts (now) claim the Suzerainty (not gold and diamonds or ‘Cape to Cairo’ British Imperialism) is the Casus Belli of the 2nd Boer War. Bet you did not learn that in your Christian Nationalism School textbook … nor do you get that conclusion from Pakenham.

In Conclusion

This is NOT say that Milner is a saint – not by any stretch, he’s a hard headed British Imperialist whose expressed desire is a Federation of States in Southern Africa, all under the oversight of the British “family” of nations – and he’s no different to just about every Federalist before and after him, men like Sir Henry Barkly. Milner is also no different to the “Afrikaner” federalists who see some form of Federation between all the states – men like Smuts, Botha, de la Rey and Hofmeyr – only they see it under an Afrikaner paramountcy and not a British one.

The Boer war is a clash of ideologies and paramountcy for complete regional oversight – and this is where Pakenham falls hopelessly flat – not only is he sparing with truths, sparing with “quotes” and sparing with ‘context’ – he blatantly sets up unsubstantiated conspiracy theory in favour of creative story telling and setting up a “good yarn” and ignores and/or manipulates the hard historical facts like the coloured and white franchise issues and the complexities surrounding the ZAR’s suzerainty – all in favour of complete fables surrounding the “gold conspiracy” and painting Milner as a “warmonger”.

The net result is “revisionist” history, a complete change in the historical narrative, and one which is so skewed to the Afrikaner Nationalist and Republicanism cause that it even had Eugène Terre’Blanche, the rabid white supremacist and leader of the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging radical far right “terrorist” group stand up and state that Thomas Pakenham’s “The Boer War” was the definitive work and final say on the Boer War – no need to read anything else!

Now, if the erstwhile “ET” said it, then you must know there is a tremendous bias – unfortunately as I’ve outlined here, this bias undermines the entire integrity of Pakenham’s work. There is merit in a lot of Pakenham’s work if you put his entire Section 1 aside, problem is Section 1 is so flawed and has so many holes in it, it can almost be classified as fiction – and here Pakenham is in effect using fiction to set up all the non-fiction in his subsequent sections – it almost stands in the same category as James A Michener’s The Covenant and Leon Uris’ Exodus. The BIG problem is subsequent Apartheid period “Afrikaner” historians and academics ensconced in institutions like the University of Pretoria, the Rand Afrikaans University (now RAU) and the University of Stellenbosch have taken Pakenham as their lead – and that now calls into the question the integrity of all their work in addition.

That is exactly why you should read the works of other authors on the Boer war, both the “original” old ones like Leo Amery’s The Times History of the South African War (Volumes 1 to 7), Deneys Reitz’ Commando and Churchill’s and Smuts’ definitive works of their involvement in the war – all the way to Rayne Kruger’s Goodbye Dolly Gray. Then we need to focus on the “new” ones like Dr Garth Benneyworth and his 2023 work on “Black” concentration camps and even his ground-breaking insights on battles like Magersfontein, or Dr Elizabeth van Heyningen’s ground-breaking work on the concentration camps and disease, or even the ‘British’ historians like Andrew Roberts FRSL FRHistS and his history of the English-speaking peoples and dare I say it Chris Ash BSc FRGS FRHistS and his book Kruger’s War.

The truly difficult thing for me is the realisation that my much-loved Pakenham’s ‘The Boer War’ is so flawed it now needs to make way for more definitive, revived, and new perspective on the subject – and luckily in un-packing Pakenham and packing him away – on the up-side, what Pakenham has done is a favour for all of us history lovers – as it now keeps a dusty old war alive as a subject – his work out of necessity and relevance now has to be counterbalanced and more critically scrutinised. For in truth, the last word on the Boer War has yet to be written.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References:

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery (1873-1955) “The Second Boer War – The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902” – Volumes 1 to 7.

The Battle of Magersfontein – Victory and Defeat on the South African Veld, 10-12 December 1899. Published 2023. By Dr. Garth Benneyworth.

The Boer War: By Thomas Pakenham – re-published illustrated version, 1st October 1991.

The Boer War: By Thomas Pakenham – Abacas Edition, 1st October 1979.

The War for South Africa: The Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) Published February 9, 2011 by Bill Nasson

My Early Life. A Roving Commission. Author: Churchill, Winston S, published October 1930.

Salisbury: Victorian Titan: By Andrew Roberts – January 2000