Often on Boer war social media appreciation sites, and even on simple things like wikipedia we see this statement “it took 500,000 British to defeat 20,000 Boers” – the much-touted ratio in this type of media is that the Boers were outnumbered 25 to 1, at a staggering disadvantage during The South African War 1899-1902 a.k.a Boer War 2.

The story goes that these plucky Boers held the mighty British empire at bay. Now that’s a figure designed to paint the Boer fighter as some sort of super-man and the British military as bumbling, monolithic and ineffective. But the truth is far from this and this figure is completely erroneous designed to drive Afrikaner nationalist political rhetoric – it has nothing to do with actual numbers on the ground.

This is why I love economic history and not political history – economic history speaks the raw numbers, the statistics – the unassailable mathematical facts, and it tends to drive great holes into the ‘political’ history and its inherit political rhetoric – its the point when the facts talk and the bull walks.

Let the numbers speak!

Now, here’s the truth – at no point in Boer war 2 were there ever 500,000 British troops in South Africa as boots on the ground at any one point in time – in total, over the course of the war the British called up 550,000 men – that bit is true, yes. HOWEVER the British rotated their Regiments in and out of South Africa on ‘tours of duty’ – never really sending a full regiment into the operational theatre at once, retaining many at home and in their other colonies around the world. The “high water mark” i.e., the maximum number of British Troops in South Africa at any one point in time is 230,000 men. Even pro-Boer chronologies like that of Pieter Cloete’s Boer War facts and figures reluctantly has to admit this fact.

This high-water mark of 230,000 (including African Auxiliaries) is only peaked briefly during the late Guerrilla Phase of the war – and at least 50,000 of these troops are being used to man the rather extensive blockhouse defence system stretching from the top to bottom and side to side across the whole of South Africa (as referenced by Simon C. Green in his Blockhouses of the Boer War) – over thousands of kilometres both ways. On average during the Guerrilla Phase of the war – September 1900 to April 1902, the British enjoy 190,000 troops on the ground.

But let’s stick to the high-water marks for a proper account – the high water for the Boer forces, total Republican forces strength is 87,365 men – including 21,043 burghers who add onto the original ZAR and OFS Commando call-up later (initial call-up is 48,216), the statutory Boer forces (2,686), foreign volunteers (2,120) and Cape Rebels (13,300).

The Boer figure is possibly higher if we add African auxiliaries and rear echelon support – the “tooth to tail” non-combatant ratio – which is accounted in the British numbers in terms of administrators, doctors, pharmacists and medics, batmen, chefs, farriers, holsters, labourers, wagon drivers etc. but NOT in the Boer numbers as this would start to add women, agteryers, servants and farm hands as people acting in Boer combat supporting roles in a non-combatant capacity.

That means a conservative ratio between Brit and Boer at the high-water marks = 230,000 Brits and 87,300 Boers – a ratio of 3:1 – total Imperial forces versus total republican forces (sans the tooth to tail ratio in the Boer number). It’s a far cry from the emotionally charged and erroneously touted figure of 25:1.

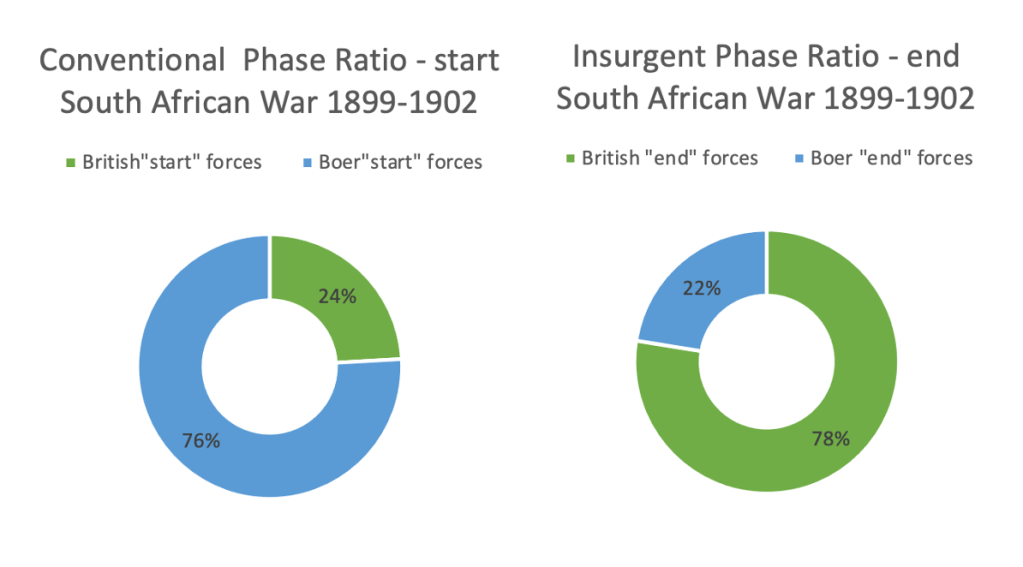

Consider the size of the Republican Forces at the beginning of Boer War 2, versus that of the British. At the Boer declaration of war on the 11th October 1899 when the Boers invade sovereign British territories: The total British Forces in the field = 15,300 men. Total Boer forces assembled to attack = 48,216 men.

The ratio is heavily in favour of the Boers – Boer Forces outnumber the British 3 to 1.

“On the high seas” as at the 11th October 1899 are an additional 7,418 British Troops on their way to South Africa from India and Australia – called up to bolster an inadequate British force strength in the event of war. Even with their arrival at the end of October 1899 (after the war has been declared and the Boer invasions commence) bringing the British number up to 22,708 – British Forces are still woefully inadequate, and the invading Boer Forces still outnumber them 2 to 1.

If we want to account Boer War 2 properly and view it with balance, it would be correct and very true to say at the beginning of the war the Boers outnumber the Brits 3:1 – as the war progresses there is a juxtaposing of numbers (they start to match capability in numbers from February 1900) … and by the end of war the Brits account 190,000 troops in country, Boers account 24,300 left in the field and 47,300 POW in the bag (factoring out the ‘Hensoppers’ and ‘joiners’ and factoring in the Cape Rebel POW) = 71,600 or a 3:1 ratio – Brits outnumber Boers, a reversal of the advantageous 3:1 ratio the Boers enjoyed at the start of the war.

Let the doctrine speak!

In terms of military doctrine, the above estimation on a 3:1 ratio is about right given Boer War 2 is fought in two distinctive phases, the Conventional warfare Phase (Oct 1899 to August 1900) and the Guerrilla warfare phase (September 1900 to May 1902) – to invade the British territory in Oct 1899 the Boers need a 3 to 1 advantage to be successful … and to counter attack and hold the Boer territory the British need to be at a 3 to 1 advantage – and even by Guerrilla Warfare standards and the doctrine used to fight one, this number is very low. Consider the following:

American Brigadier-General Nelson Miles was put in charge of hunting down Geronimo and his followers in April 1886. Miles commanded 5,600 troops deemed necessary to find and destroy Geronimo and his 24 warriors. In Malaya in 1950 it took 200,000 British, Australian and allied troops to defeat 5,000 Communist guerrillas. In Ireland over the 30-year course of ‘the troubles’ a total of 300,000 British troops were used to contain 10,000 IRA guerrillas. Closer to home, so the arm chair Boer war generals get this – over the course of the Angolan Border War (1966-1988) and the ‘Struggle’ (1960-1994) the SADF would call up 650,000 conscripts and then hold them in reserve – MK and other non-statutory force ‘guerrillas’ at their high water mark in 1990 only have 40,000.

The modern-day theoretical ratio of counter-insurgency forces to guerrillas needed to defeat an insurgent/guerrilla campaign is 10:1. In 2007, the US Department of Defence produced a document entitled Handbook on Counter Insurgency which quotes this as the rule-of-thumb ratio for all such operations – and that is even with the advent of modern technology in warfare fighting mere insurgents or guerrillas. Little wonder that General David Petraeus needed 180,000 coalition force troops (the same size as the full invasion force) on the ground in 2007 just to deal with the Iraqi guerrilla “surge” spearheaded by an insignificant but determined bunch of suicide bombers.

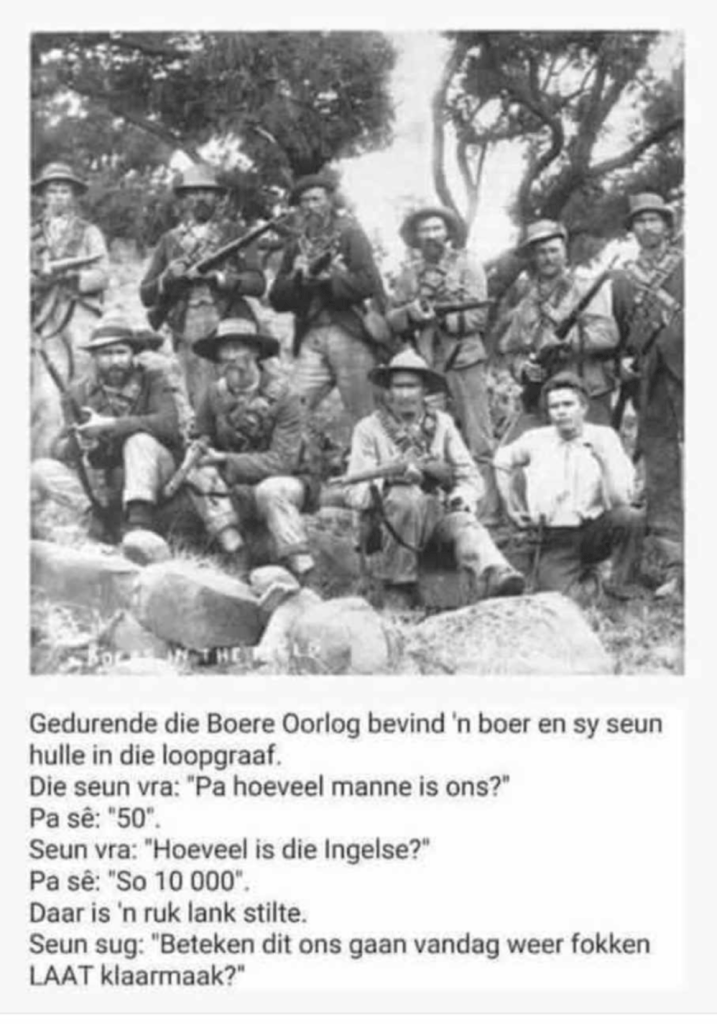

Just kidding!

The idea that it took half a million British troops to subdue a couple of thousand boers is very erroneous .. the old ‘super’ Afrikaner joke – on witnessing an advancing British ‘rooineck’ column a Boer kid asks his Dad “how many Boers are we Dad? – Answer “50 son”, and “how many British Dad?” – Answer “10,000 son”. Punchline … “Dad, does this mean we’re going to finish late again?” A joke that re-appears in different formats in countless forums, and it’s as funny as it’s statistically false and fantastical.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References – all quoted statistics

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery “The Second Boer War – The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902” – Volumes 1 to 7.

History of the war in South Africa 1899-1902. By Maj. General Sir Frederick Maurice and staff. Volumes 1 to 4, published 1906

The Anglo-Boer war: A chronology. By Cloete, Pieter G

Anglo-Boer War Blockhouses – a Field Guide by Simon C. Green, fact checking and correspondence – 2023.

The Boer War: By Thomas Pakenham – re-published version, 1st October 1991.

Correspondence and interviews with Dr. Garth Bennyworth, Boer War historian – Sol Plaatjies University, Kimberley – 2023.

Correspondence on fact checking British doctrine with Chris Ash, BSc FRGS FRHistS, 2023 – Boer War historian, Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

Kruger’s War – the truth behind the myths of the Boer War: By Chris Ash, published 2014.

Related work:

Boer War by the numbers: Boer War by the numbers!

So the victorious British will write the history in a way that they are the hero’s in a scorched earth war with THOUSANDS OF DISPLACED CIVILIANS !!!

LikeLike

Exactly which of the statistics presented in the article are you querying, and what are you references?

LikeLike

Mr Dickens,

My thanks for this, as always.

It always goes down to “Lies, Dam’d Lies and Statistics.”

The following is about as accurate as I can get it, by using primary sources, in the National Archives (which included the written records from The Old War Office Library) London, and those held in the Australian War Memorial, State Libraries of Victoria and NSW.

31st May Final meeting at Vereeniging. After further negotiations with Kitchener and Lord Milner (British High Commissioner in South Africa), the Boer delegates accept the peace proposals by 54 votes to six. The terms of surrender were officially signed (Peace of Vereeniging) in Melrose House (in 2013 a museum), Pretoria.

On this day (as per the Strength Returns and Ration State’s, separate documents) there were (rounded figure) 202,000 British Army and Colonial Forces on duty throughout South Africa, this not including part-time units such as Town Guards, District Mounted Troops and suchlike (probably some 23,000 men), but does include the wartime raised militarised police (such as SAC) and non-European Auxiliaries. The 202,000 comprised the static troops in the blockhouse lines, POW guards, defence of significant sites, garrisons of the two former Republics, logistic and HQ troops, sick and those in prison, some 60,000 actually provide the mobile columns, some ten percent of whom were resting, retraining and preparing to go out on column at any one time.

Incorrectly, many sources state that there were 450,000 British troops in SA, this figure approximating the total number of British and Colonial troops (448,435, not including multiple enlistments) who served throughout the war, and equates to the issued number of QSA Medals (400,000 plus) or KSA Medals awarded singly (not in conjunction with the QSA Medal (1) on expiry of their engagements, large numbers of Yeomanry and Colonial troops re-enlisted into other units for short periods, and then re-enlisting into others; The figure of 30,000 Black South Africans is quoted as fighting as part of the British Army, this figure whilst it does include armed men serving as auxiliaries under European NCOs as guards on the blockhouse lines (2,500-3,000), the vast majority were such as animal transport drivers, stockmen, labourers with the Royal Engineers, vital logistic employments, but they were not combatant soldiers. Equally, there were a large number of Europeans serving the various logistical needs of the British throughout the war, these not entitled to the award of any medals, as they non-combatant civilian contractors.

NOTE : In 2013 a internet ‘pay for database’ gave 271,771 names, 59,000 being casualty records.

There discrepancies in the Casualty figures between the Official History and those recorded in ‘The Times’ Volume VII, whose figures are shown in brackets. Killed in Action, accidental deaths (including one killed by a crocodile on the Usutu River), or Died of Wounds 7,582 including 712 officers (7,894, 706 officers); died of disease 13,139 including 406 officers (13,250; 339 officers), Total Deaths 20,721 (21,942),includes 934 missing, there 22,828 wounded. WATT, below, lists civilians and Black Auxiliaries, and missing, giving just over 25,000. Other sources give different figures.

The last known casualty of the War; Private L.Maritz, Damant’s Horse, died of wounds, Bloemfontein, 14th June, 1902.

While for the Transavaal and the OFS 6,189 dead, unknown numbers missing, and wounded, 21,256 bitter-enders surrendered, prisoners taken, see below. Cape Rebels, see below.There discrepancies in the Casualty figures between the Official History and those recorded in ‘The Times’ Volume VII, whose figures are shown in brackets. Killed in Action, accidental deaths (including one killed by a crocodile on the Usutu River), or Died of Wounds 7,582 including 712 officers (7,894, 706 officers); died of disease 13,139 including 406 officers (13,250; 339 officers), Total Deaths 20,721 (21,942),includes 934 missing, there 22,828 wounded. WATT, below, lists civilians and Black Auxiliaries, and missing, giving just over 25,000. Other sources give different figures.

The last known casualty of the War; Private L.Maritz, Damant’s Horse, died of wounds, Bloemfontein, 14th June, 1902.

While for the Transavaal and the OFS 6,189 dead, unknown numbers missing, and wounded, 21,256 bitter-enders surrendered, prisoners taken, see below. Cape Rebels, see below.

LikeLike

Mr Dicken,

the second part of my response./Yours,

G/.

BOER PRISONERS OF WAR. There were approximately 27,000 Boer prisoners and exiles, comprising three categories: prisoners of war, ‘undesirables’ (see No 1,276 Port Alfred Imperial Mounted Police) and internees. POW being those captured while under arms. Detained in South Africa in camps in Cape Town (Green Point) and at Simonstown (Bellevue), and some in gaols in the Cape Colony and Natal; in the Bermuda Islands in camps on Darrell’s, Tucker’s, Morgan’s, Burtt’s and Hawkins’ Islands; on the island of St. Helena in the Broadbottom and Deadwood camps, and the recalcitrant’s in Fort Knoll; in India at Umballa, Amritsar, Sialkot, Bellary, Trichinopoly, Shahjahanpur, Ahmednagar, Kaity-Nilgris, Kakool and Bhim-Tal; on the island of Ceylon in Camp Diyatalawa and smaller camps at Ragama, Hambatota, Urugasmanhandiya and Mount Lavinia (the hospital camp). The internees were Transvaal burghers and their families who had crossed the Colonial Portuguese border to Lourenço Marques and held at Komatipoort, subsequently shipped to Portugal, where they were interned at Caldas da Rainha, Peniche and Alcobaqa. Some 3.5% of Boer POW died whilst incarcerated, in the main, due to natural causes or accident, with a small number by their own hand or murdered by their compatriots, those killed by the captors less than those two combined. Numerous daring escape attempts were made, but few were successful. Five POW; Lourens Steytler, George Steytler, Willie Steyn, Piet Botha and a German named Hausner; swam out to a Russian ship in the port of Colombo, travelled via Russia, Germany, the Netherlands finally landing at Walvis Bay. From Bermuda, two succeeded in reaching Europe having stowed aboard ships. One, J.L. de Villiers escaped from Trichinopoly disguised as a coolie and made his way to the French possession of Pondicherry, reaching South Africa via Aden, France and the Netherlands. With the War’s end, a number did not return to South Africa. Two brothers named Van Zyl and a German held in Ceylon went to Java, where they developed a Friesland cattle stud for a milk industry. From Bermuda, a number went to the United States of America and Mexico. While from the Cape, a number escaped with the connivance of Cape Boers.

The first sizeable batch of Boer POW taken by the British, consisted of those captured at the battle of Elandslaagte on 21st October, 1899, which resulted in the capture of 188 Boers. No camps had been prepared, and by arrangement with the Naval authorities these prisoners (approximately 200 men), were temporarily housed on the guard ship HMS Penelope in Simon’s Bay. Several ships were used as floating prisoner of war camps until permanent camps were established at Greenpoint, Cape Town and Bellevue, Simonstown. The first prisoners were accommodated in Bellevue on 28th February, 1900. Wounded prisoners were sent to the old Cape Garrison Artillery Barracks at Simonstown which had been converted into the Palace hospital. The first wounded arrived on 2nd November, 1899.

Towards the end of 1900, with the first invasion of the Cape Colony, the prisoners at Cape Town and Simonstown were placed on board ships. At the end of December 1900, some 2,550 men boarded the SS Kildonan Castle where they remained for six weeks before they were removed to two other transports at Simons’ Bay. The camp at Ladysmith, Natal, was in use from 20th December, 1900 until January 1902. It mainly used as a staging camp although it had some 120 prisoners of war. Another staging camp was also established at Umbilo in Natal. As the number of prisoners grew, for example at Paardeberg, the decision was taken to hold the prisoners away from South Africa. There was nowhere that was suitable in South Africa, with the problems of transport, the possibility that prisoners might be freed by their comrades, and the burden of feeding the men.

Of the 28,000 Boer men captured as prisoners of war, 25,630 were sent overseas. 577 died, at sea 77. The approximate (and contradictory) numbers of prisoners by camp was:

St Helena, 5,866 (The first such camp) 171 died (two aged 74) on the island, and one (an Italian) made a successful escape. Salmon A.G.Harmse died of Typhoid Fever on St. Helena 6th July, 1902. Serving in Potchefstroom Commando when taken prisoner with his father, B.J.F. at Paardeberg, 27th February, 1900. The POW Register (POW No. 1191) states his age at time of capture 16, the brochure Die Bannelinge (The Exiles), War Museum of the Boer Republics, Bloemfontein, 1983, confirmed age on death. His father applied for his son’s medal February 1922.

Ceylon, 5,126 (Second location for camps) 156 died, mythology tells 144 years old, W.J.R.Bretz, of Bloemfontein?

Bermuda 4,619 (The third location for camps) 31 died in its camps, and six whilst enroute?

India 7,673, located within some 20 British Army cantonments. 142 died, youngest POW to die overseas, 8 year old David Jacobs (POW No. 29757) captured Straithnairn 27th February, 1902, died of measles in Bellary, India 19th April.

Portugal 1,443 interned in Mozambique.

The grand total number of prisoners :

56,457 Transvaal POW, 12,954 Surrendered during the war.

13,780 OFS POW 12,358 Surrendered during the war,

Cape Rebels, 15,433 served, 3,442 surrendered at war’s end, 700-800 fled to the Republics, 100 into Angola; 7,587 left Transvaal via Delagoa Bay and 1902 8,318 Rebels awaiting trial, convicted, and disposed of; 400 escaped to German SWA; 200 made POW in error; 700 Alien Foreigners (of whom 160 POW); 44 Cape Rebels suffered judicial execution.

TEXT: JOOSTE Graham, WEBSTER Roger. Innocent blood : executions during the Anglo-Boer War. New Africa Books, Claremont, 2003. Illusrated card, 240p., illustrations. Also covers Republicans and Coloureds executed.

REPATRIATION OF THE BOER PRISONER OF WAR. As early as 1901, Lord Milner realised what a huge task the resettlement of some 200,000 Europeans involved, among whom were about 50,000 impecunious foreigners who mainly had been employed on the Witwatersrand, and approximately one million Bantu, who as a result of the War, had become torn from their usual way of life and had either placed into POW and internment camps or scattered all over the Orange Free State and the Transvaal as refugees and combatants. All of these had to be restored to their shattered world in order to become self-supporting. Milner wished Britons employed by the Transvaal mines and industries to be repatriated first. This began after the annexation of the Transvaal in 1900. By February, 1901, some 12,000 had already been repatriated, by the beginning of 1902, the bulk had returned to the Witwatersrand. To aid the resettlement of former Republican subjects, special Land Boards were set up early in 1902 in both the new colonies. They were also expected to help settle immigrant British farmers. From April, 1902, the repatriation sections of the Land Boards were converted into independent departments in order to prepare for the repatriation of the Afrikaner population. The post-war development of the repatriation programme was adumbrated in sections I, II and X of the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging. In terms of sections I and II all burghers (both ‘Bitter-enders’ and prisoners of war) were required to acknowledge beforehand the Monarchy as their lawful sovereign. Section X read that in each district local repatriation boards would be set up to assist in providing relief and in effecting resettlement. For that the British government would provide three million pounds as a ‘bounty’ and loans, free of interest for two years, and after that redeemable over three years at 3%. The wording ‘vrije gift’ (free gift), as the bounty termed, gave rise to serious misunderstanding, and the accompanying provision, that proof of war losses could be submitted to the central judicial commission, created the erroneous impression that this bounty was intended to compensate the burghers for these losses. The eventual interpretation, that the bounty was intended as a contribution toward repatriation, created a great deal of bitterness. Eventually, it turned out that there was no question of a bounty, since repatriates were held personally responsible for all costs, the £3m part of the loan of £35m provided by the British Treasury for the colonies. After the conclusion of peace two Central Repatriation Boards, one each in Pretoria and Bloemfontein, began to function, 38 Local Boards were set up in the Transvaal and 23 in the Orange River Colony. The repatriation departments were reformed into huge organisations, each employing more than 1,000 men. The real work of repatriation came in three strands, returning farmers back to their farms with the least delay; supplying them with adequate rations until they could harvest their crops; and providing them with seed, stock and implements to cultivate their lands. The general discharge of POW within South Africa began June, 1902. Many overseas POW, especially those in India, were sceptical about the peace conditions and refused to take the oath of allegiance to the British Crown. In spite of the efforts of General De la Rey and Commandant I.W. Ferreira to induce them to return, some 500 of the 900 ‘irreconcilables’ could not be persuaded until January, 1904. In July, 1904, the last four Transvaalers were discharged from India, but in May, 1907, two Free Staters still remained (they eventually returned). Each transhipment contained comprised 100 men per district per ship, and upon arrival they were sent to camps at Umbilo and Simonstown,. Those who were self-supporting were allowed to go home, being given free food and clothing for their journey. Through judicious selection, land-owning families first and ‘bywoners’ (share-croppers) next, repatriation was made bearable. By mid-June, 1902, almost all the ‘bitter-enders’ had laid down their arms and were allowed to return to their homes, provided they could fend for themselves. In other cases, they were allowed, like the POW, to take up temporary accommodation with their families in internment camps until they were sent home by the repatriation departments with a month’s supply of free rations, bedding, tents and kitchen utensils. By September, 1902, only the impoverished group was left in the camps. With the creation of relief works, such as the construction of railway lines and irrigation works, created employment for them. However, a considerable number of pre-war share-croppers became chronic “Poor Whites”, becoming a ongoing thorny problem until post-1948 Election, the Nationalist Government created government employment for them. The repatriation was fraught with problems. Some 300,000 asset-less people had to be brought back to a devastated rural environment. Supplies had to be conveyed over vast distances of badly damaged unformed roads and worn out railways, already heavily burdened by the demobilisation of the British forces and the transport of supplies to the Rand. The organisation was ineffective, and the authority and duties of the central and local repatriation boards were too vaguely defined, leading to unnecessary duplication. Moreover, the burghers mistrusted the repatriation. By the end of 1902 most of the ‘old’ population had, however, been restored. The long drought that dragged on from 1902 until the end of 1903 made it necessary for many of the repatriation depots to be kept going until 1904, in order to keep the starving supplied on credit. From 1904 conditions gradually improved, and in 1905 repatriation was complete. A great deal of the 14 million pounds spent on it had gone into the cost of administrating the movement, feeding and accommodating the men and their families. Sharp criticism was levelled against the repatriation policy, especially against the incompetence and lack of sympathy among the officials, and financial mismanagement. The composition of the repatriation boards was also suspect. However, agricultural credit came in with repatriation and prepared the way for what became a long time system of Land Bank loans and co-operative credit. Milner himself considered the repatriation a success, although he conceded that a considerable sum of money had been squandered. it was not the utter failure that the Nationalists subsequently represented it to have been. Milner made a genuine attempt to resettle an impoverished and uprooted rural population and to reconstruct an entire economy. The accomplishment of the entire project without serious friction can largely be attributed to the genuine efforts of both sides.

LikeLike

Hi Gordon, thank you once again for such great feedback and I’ve learned one or two things today no doubt. You’re right in the world of statistics if you have one hand in boiling water and another in freezing water, on average you’re comfortable. Trying to pull statistics for the Boer War is no easy task as they vary so much. In the end I’ve gone with the figures on Boer Forces at the beginning of the war presented by Leo Amery’s “The Second Boer War – The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902” and the “History of the war in South Africa 1899-1902”. By Maj. General Maurice. I’ve also consulted with work done on his by Meurig Jones. As to closing statistics, I again looked to the above and also to the more conservative statistics from The Anglo-Boer war: A chronology. By Pieter Cloete. Notwithstanding the greatest challenge here is to account the African auxiliaries, and even Tswana and Swazi Impi combatants – one is also left with the “tooth to tail” ratio – which while prevalent in the British statistics (covering logistical support, administration, finance, non-combatant roles – camp administrators, doctors, pharmacists and medics, batmen, chefs, farriers, holsters etc) not prevalent at all in the Boer statistics (people acting in service and non-combatant roles – agteryers, servants, farms hands and family). Later historians have tried to make a realistic fix on this to compare “apples with apples” In either event, between the figures presented by the ‘British’ historians and those by the ‘Boer’ historians – luckily although the totals differ, the ratios generally don’t. One thing I can say, it’s generally one heck of a job and I’m sure there will be loads of debate one way and another. Many thanks for this outstanding input again.

LikeLike

The accurate authorities are of course unit ration and parade states. But they frequently do not list various types of hangers on.

For instance one W.S.Churchill is not shown on either for the various corps he served with in the War (his QSA was named to War Correspondent).

to allow for the feeding of unauthorised colour or blacks, the QMs used to bodgie the ration states and acquire foodstuffs that British soldiers would not eat. Rice being the main one, arrowroot, semolina and such like.

The Cape Records when they still extant in 1997, had a vast amount of such primary records. What you see in my responses is the result of check and counter-checking primary sources. At the regimental level usually spot on when it arrived in the various civilian run departments is where problems occurred.

There is no way in the world that I would make an attempt to get a accurate record, so much primary records in South Africa have been lost. Those in the National Archives in the main deal with British Army, and these can be nightmares, I had a quick look at the various files on Yeomanry companies, quickly coming to the conclusion that mucking about with them would reduce me to alcohol abuse!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Any idea of the rotation (rest) of Boer forces during the ABW, comparing to British forces being rotated?

LikeLike

The Boers did not generally rotate their forces like the British. There is slight erroneous account after the amnesty is declared when the Conventional Phase concludes of Hensoppers and Joiners who leave their commandos, and in the case of Hensoppers – many are forced to join their commandos again despite taking an oath not to. The same thing happens with Boer POW who take the oath, are released and then re-join their commandos. To give an idea of how complex this is, some sources point to nearly a quarter of all standing Boers “in the field” at the end of war as been “Joiners” and not “Bittereinders” a 1:3 ratio. The best way to figure all of that is to simply look at the “high water marks” and compare apples with apples.

LikeLike

From books it appears that Boers, from own volition, individually just “took” leave from military service and went home for “time off”. But nowhere is this quantified. It also does not appear that daily roll-calls were done.

LikeLike

I’ve seen accounts in the beginning of the war by Veldkornets and Kommandants that their fighting capability was affected by Boers packing up and simply heading home. This is somewhat corrected in the later stages were Commando service becomes mandatory and Generals like Botha stamp this practice out. It’s not helped by the fact that officers in Commando’s were often appointed on a popularity vote and not necessarily on skill.

LikeLike

Excellent article as always.

I am glad you mention that the Imperial high command had to ‘waste’ their manpower in scattered garrisons / blockhouses and / or tasked with protecting lines of communication, bridges, and railways, or holding towns and villages far from the fighting. These static troops, militias, and town guards meant that only eleven per cent of Kitchener’s troops were available for offensive operations against the bittereinders.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Peter Dickens slays the sacred cow of Boer War myth – Chris Ash – Author

Another thing which (conveniently for their modern-day apologists and Defenders of the Myth) artificially makes the numbers of republicans look much lower than reality is that, while the thousands of signallers, engineers, pioneers, and service corps personnel are all considered when adding up the number of Imperial troops who served in southern Africa, the thousands of blacks who performed similar tasks for the Boers is generally overlooked. Obviously, the British also made use of Africans as wagon drivers, labourers and the like, but the republicans took this to another level, with many Boers taking their African ‘boys’ on commando with them:

‘All behind-the-line services on commando were carried out by black people, who constructed fortifications, herded horses and cattle, drove wagons, and performed labour duties in military camps. Many burghers were accompanied by one (or more) of their servants who acted as an agterryer (after-rider), performing such tasks as supervising his employer’s horse, loading his rifles while in combat, and in exigent circumstances, fighting alongside him.’

And yet these tens of thousands of what were essentially rear-echelon troops are never considered when assessing the size of the republican forces. In contrast, the 8,500 doctors and hospital staff of the British Army Medical Corps who served in South Africa in 1902, for example, are always included in the Imperial total. Also included are the thousands of Royal Engineers in the theatre which, in December 1900, included a telegraph battalion, two bridging units and three balloon sections.

LikeLike

You make a very valid point Chris, what we like to sarcastically call a REMF in a modern military – whilst Rear Echelon is accounted in the British numbers it’s almost never accounted in the Boer numbers. Not fully known is the full contingent of Agteryers – or the full contingent of labour used to dig good earth works in rock hard ground to convert dongas to trenchers at Magersfontein for instance. We do see examples of women accompanying their men-folk on Commando in rear wagons providing support (cooking for starters) – the Battle at Paardeberg gives clear reference of them, so too at Derdepoort when the Tswana attack this rear echelon support laager – but for some reason they are excluded from the numbers. I tried to reference this in the “tooth to tail” ratio – to say that it is included in the British figures but not in the Boer ones. One also has to remember the British ‘Army Force’ was a full contingent operating as its own body on foreign soil, rammed full of administrators, pay officers, surveyors, staff officers, intelligence officers, engineering experts, logistics and supply experts, liaison officers between arms of service and medical and pharmaceutical support, veterinarians, blacksmiths and farriers – you name it – none of it “combatant”.

LikeLike