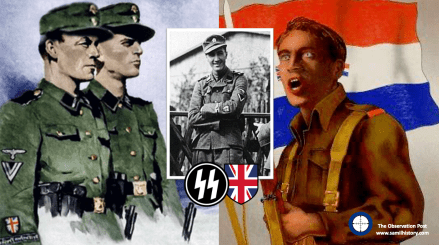

Springbok Renegades: South Africans serving in the British Free Corps of the Waffen SS during the Second World War.

By Peter Albert Dickens

Introduction

In military history circles, there is an often asked question. How many South Africans served in Nazi Germany’s Armed Forces? This is usually followed by an enquiry on these “renegades” and if they were ever brought to book.

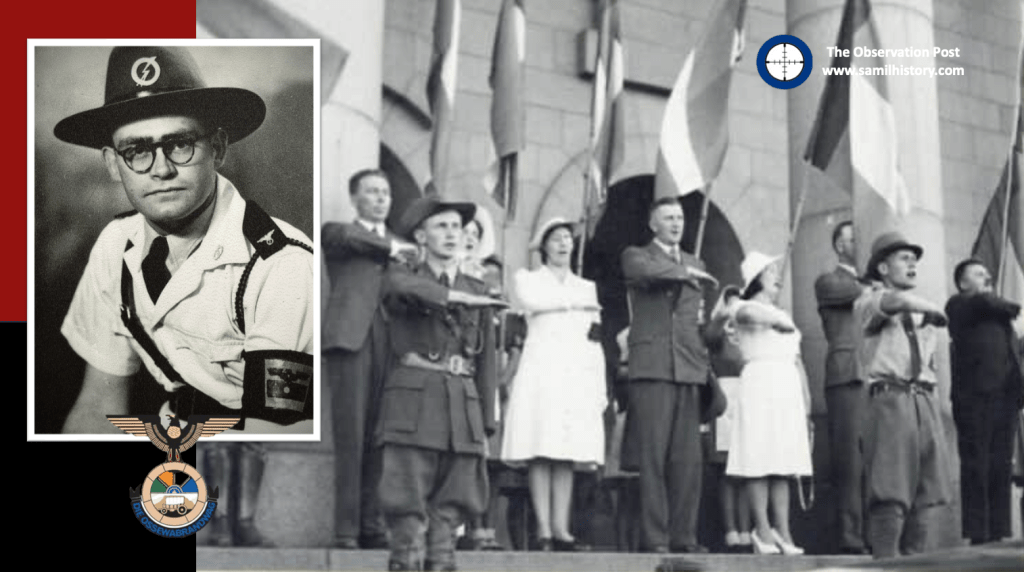

Because of all the publicity it generated many people are aware of Robey Leibbrandt – the firebrand Afrikaner insurgent who trained as a German Paratrooper and special forces operator, sent to South Africa to take over the Ossewabrandwag and direct a Afrikaner Nationalist revolt to topple Smuts. His capture and sentencing a well known aspect of Afrikaner Nationalist lore, so too his eventual pardon by the National Party in 1948.

Some are aware of Leutnant (Lt.) Heinz Werner Schmidt, who was one of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s personal aids in the North African conflict – and that’s because after the war he re-settled back in South Africa and published a book “With Rommel in the Desert”. As a standard Wermacht officer (Germany Army – Statutory force) with a dual national status (known as Volksdeutsche – a foreign national with German heritage) he was often just viewed with interest. There were also a small number of South West Africans (Namibians) who found their way into German forces because of their German national heritage – notably here is another member of Rommel’s staff, his driver Leutnant (Lt.) Hellmut von Liepzig.

But what of the rest? Surely there are more.

The truth is there are some more, not many mind – but there are more – known as ‘Renegades’ they can be found in all sorts of Nazi German military and propaganda structures. After the war some South Africans were arrested, some having served in the German Waffen SS, and they surrender to the Allied forces occupying Germany in 1945, to a man all claiming they were just fighting against the Communist onslaught of the Red Army. Theirs is an interesting story and also a complex one, as they do not volunteer to join Germany upfront, they all join the South African Army upfront, and they have no dual German nationality or stated German affinity – they are South African soldiers pure and applied – affectionately known at the time in South Africa as ‘Springboks’ – mid way through the war they change sides, put on German uniforms, and take up arms against their own country and its Allied forces – they all join the infamous Nazi German Waffen SS (the Nazi party and Hitler’s personal army) in a special ethnic unit set aside for ‘British’ renegades – but why this extraordinary ‘volte-face‘?

It’s a very complex question, to understand their motives for committing such an act of treason we need to understand the background as to Nazism and anti-Communism in both South Africa and the United Kingdom – and the political landscapes driving each.

The bedrock of Nazism and anti-Communism in South Africa

The background to South African Nationals joining the Nazi German Waffen SS, and other German forces for that matter, lies against the background and popularity of National Socialism and Fascism as ideologies prior to the Second World War in South Africa and in the United Kingdom respectively. Within this context we find a variety of home grown National Socialist and Fascist movements incorporating fierce anti-Communist and anti-Semitic ideologies. Even the mainstream opposition and governing political parties in South Africa and the United Kingdom had strong anti-Communist leanings. This socio-political dynamic forms the backdrop to understanding the motivations of British, South African, and other Commonwealth citizens joining the German forces during the war. In the Waffen SS, an overarching proposition put to foreign recruits, and to motivate them join, was to fight alongside Nazi Germany forces to prevent the onset of Bolshevism (Communism).

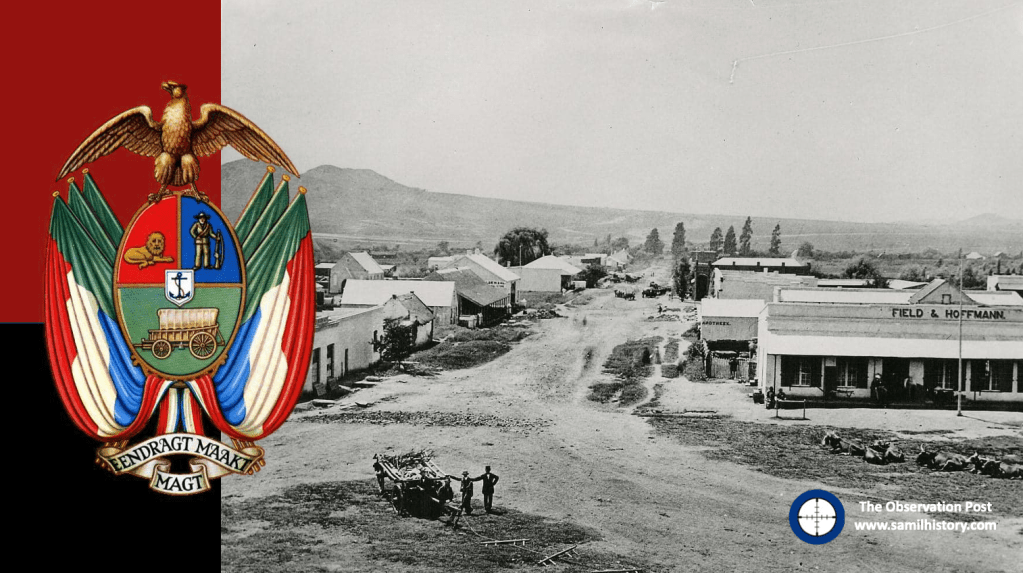

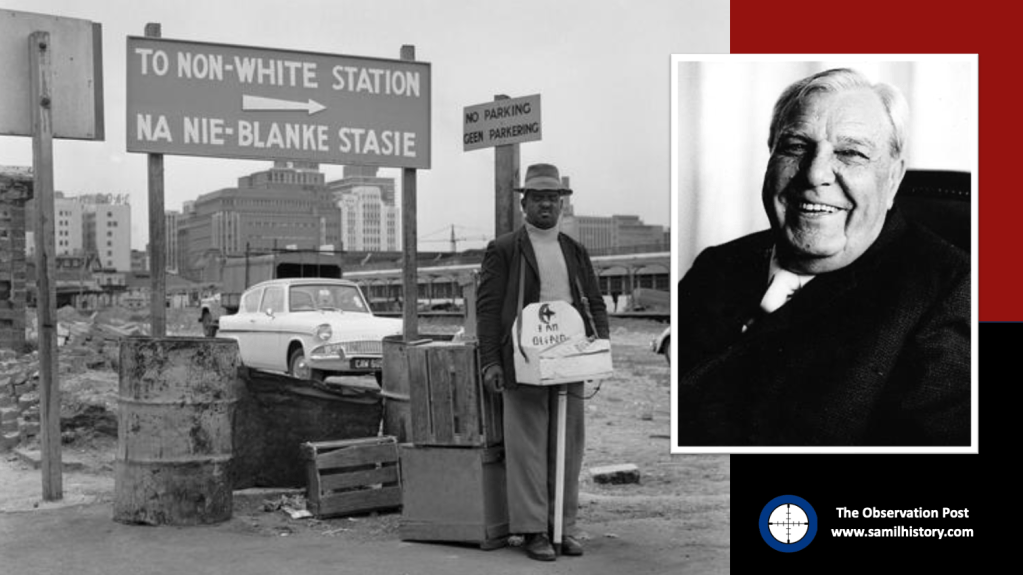

Prior to the Second World War, South Africa was governed by a Fusion party created between General James Barry Munnik Hertzog’s National Party (NP) and General Jan Christian (JC) Smuts’ South African Party (SAP) in 1933, this party came about to tackle the economic challenges of the Great Depression and also sought to maintain a Afrikaner led hegemony in the interests of South Africa’s white population.1 Hertzog led this fusion undertaking as Prime Minister with Smuts as his deputy. Known as the United South African National Party, or simply the “United Party”2 it contained within it a component of Afrikaner nationalists harbouring republican desires and a component within it of Afrikaners satisfied with Union and South Africa’s status as a British Dominion.

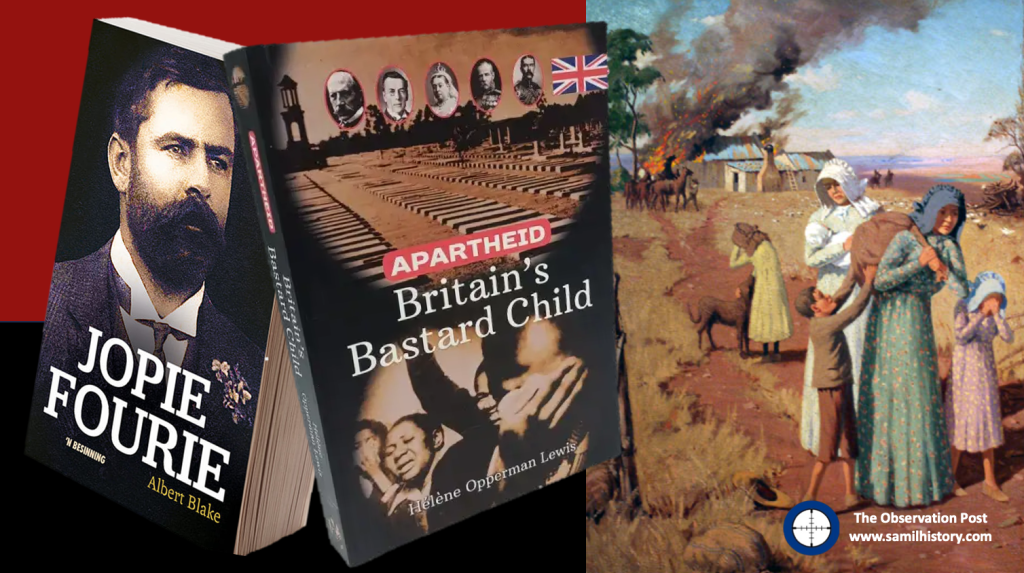

Afrikaner nationalists to the political far right of their colleagues who had now joined the United Party were unhappy with the idea of Fusion. Led by Dr. Daniël François (D.F.) Malan this grouping of dissatisfied nationalist broke away from Hertzog’s old National Party and reconstituted themselves as the ‘Purified’ National Party (PNP) in 1935.3 The ,central objective of the PNP was a complete break with Britain and the establishment of an independent oligarchy Republic under a white Afrikaner hegemony.4 Anglophobia was a critical ideology underpinning DF Malan’s PNP. This resulted from the scorched earth policy used during The South African War (1899-1902) by British forces, and Malan sought to exclude English speakers from the PNP completely.5 The Purified Nationalists became the official opposition after the General Election held on 18 May 1938.6

Since the Union of South Africa’s declaration of war against Imperial Germany in 1914, and the invasion and annexation of German South West Africa (GSWA) shortly thereafter, a bitter internal debate had raged amongst Afrikaner Nationalists across the political spectrum. The invasion of GSWA was led by General Louis Botha and General Jan Smuts and supported by the ruling party – the SAP. Primary motivations included supporting Britain and France’s war effort. However, another key objective for South Africa’s invasion of GSWA was a domestic one as the war presented an opportunity for South Africa’s own territorial ambitions. The 1909 Conference for a Closer Union and the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910 had within its construct the initial inclusion of GSWA in addition to Southern Rhodesia, Delagoa Bay, Bechuanaland, Lesotho and Swaziland in the Union.7

However, for cultural and historic grounds large swathes of the white Afrikaner community held sympathies for Germany. They believed Germany had supported them during the South African War and hence sought neutrality instead.

The resultant failed Afrikaner Rebellion of 1914, pitching Afrikaner against Afrikaner over the invasion of GSWA, left a long legacy of more bitterness and even deeper political polarisation. The country was further divided on racial fault lines with the majority of the black indigenous population groups on the political periphery, with little attention paid to their political aspirations and emancipation.

In the inter-war years (1918-1939), and with the rise of National Socialism in Germany and Fascism in Italy from the mid 1920s, many Afrikaner Nationalists increasingly came under the influence of Adolf Hitler and his specific brand of German National Socialism (Nazism). With this came their abhorrence for Communism. Oswald Pirow, Hertzog’s Minister of Defence (1933-1939), was one of the most influential Afrikaners to fall under Hitler’s spell. Pirow met with Hitler, Hermann Göring, Benito Mussolini and Francisco Franco8 as an envoy on behalf of the United Party government. Pirow received Germany’s feedback on GSWA and the ‘new order’ should Germany go to war with Britain and her allies. Pirow gambled his career on a Nazi Germany victory in what he saw as an inevitable war. On 25 September 1940, he founded the national socialist ‘New Order’ (NO) for South Africa. He positioned it as a study group within the reformulated National Party (HNP), and based it on Hitler’s new order plans for Africa.9 During the Second World War, Pirow also positioned the NO as a defender of whites in Africa against the threat of Communism.10 In terms of the NO’s values, Pirow espoused Nazi ideals and advocated an authoritarian state.11

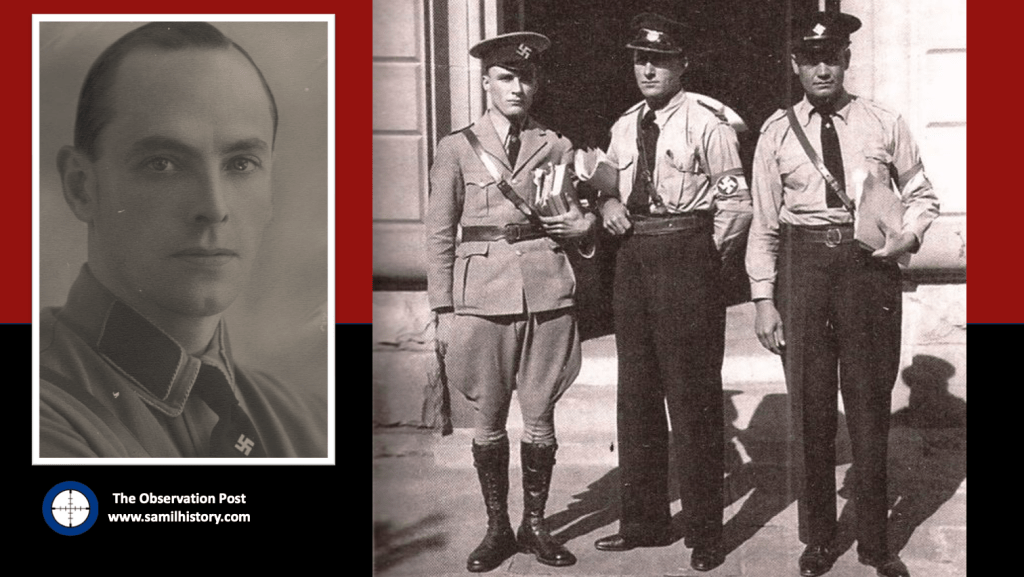

In addition to Oswald Pirow’s NO, other leading and influential Afrikaner Nationalists were forming German National Socialist movements with distinctive antisemitic and anti-communist leanings in South Africa during the interwar period. As a committed antisemite, Louis Theodor Weichardt founded the South African Christian National Socialist Movement when he broke with the National Party on the 26 October 1933. This included a paramilitary ‘security’ or ‘body-guard’ section (modelled on Nazi Germany’s brown-shirted Sturmabteilung) called the “Gryshemde” or “Grey-shirts”. In May 1934, the paramilitary Grey-shirts officially merged with the South African Christian National Socialist Movement and formed a new enterprise called ‘The South African National Party’ (SANP). The SANP would continue wearing Grey-shirts as their identifying dress and would also make use of other Nazi iconography, including extensive use of the swastika.12 Overall, Weichardt saw democracy as an outdated system and an invention of British imperialism and Jews.13

Weichardt also pitched the SANP as a fully bilingual organisation appealing to both English and Afrikaans speakers, he found favour in some English speaking corners with hardened antisemites, however for the most part his organisation and its ideology appealed to Afrikaners.

Other neo-Nazi and fascist groupings either spun out of the SANP Grey-shirts, or mushroomed as National Socialists movements with the German model front and centre in their own right. Also included was Manie Wessels’ ‘South African National Democratic Movement’ (Nasionale Demokratiese Beweging) formed in Johannesburg. They became known as the “Black-shirts”, and operated in the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. The ‘Black-shirts’ form in opposition to the ‘Grey-shirts’ anti-democracy position and look to a more “purified” whites only democracy free of Jewish and Capitalist influence.14

The Black-shirts themselves would splinter into another Black-shirt movement called the ‘South African National People’s Movement’ (Suid Afrikaanse Nasionale Volksbeweging). Started by Chris Havemann and based in Johannesburg, these Black-shirts advanced a closer idea of National Socialism. By 1937 this Black-shirt splinter group boasted 265 branches mainly in the Transvaal. ‘The Swastika’ was their official mouthpiece.15

Another National Socialist movement known as the ‘African Gentile Organisation’ was also formed in Cape Town by HS Terblanche in September 1934, Dr AJ Bruwer formed the ‘National Workers Union’ (Bond van Nasionale Werkers) in Pretoria – also known as the “Brown-shirts”. Additionally, Frans Erasmus formed another national party militant group called the “Orange-shirts”.16

Two National Socialist movements broke away from the SANP Grey-shirts, when the SANP leader JHH de Waal resigned and formed the ‘Gentile Protection League’. Their sole aim was to fight the ‘Jewish menace in South Africa’.17 Johannes von Moltke, Weichardt’s right hand man, then broke away from the SANP along with most of his Eastern Cape constituency. They formed a new organisation called ‘The South African Fascists’ who wore Nazi iconography, blue trousers, and Grey-shirts.

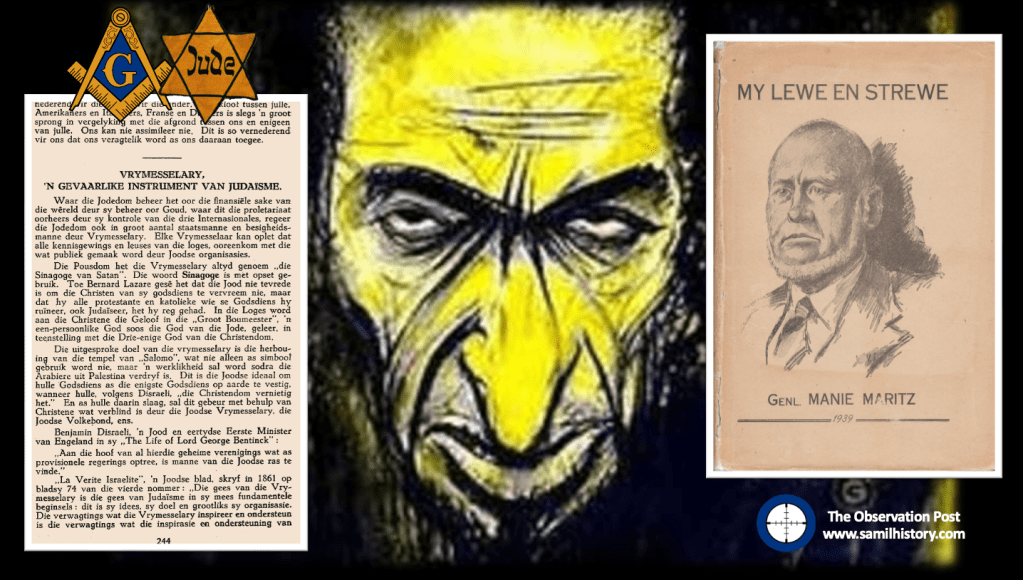

Additionally, Manie Maritz, a veteran of the South African War and influential leader of the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion, also admired German National Socialism. A converted antisemite, he even blamed the South African War on a Jewish conspiracy. He founded the anti-parliamentary, pro National Socialist, antisemitic ‘Volksparty’, in Pietersburg in July 1940.18 This evolved and merged into ‘Die Boerenasie’ (The Boer Nation), a party with National Socialist leanings originally led by JCC Lass (the first Commandant General of the Ossewabrandwag) but briefly taken over by Maritz until his accidental death in December 1940. Thereafter it was headed up by SK Rudman.19 Maritz would also detail his Antisemitic and National Socialist views in his autobiography ‘My Lewe en Strewe’ (My life and Aspiration) published in 1939 and modelled on Hitler’s own ‘Mein Kampf’. 20

Aside from all these various parties, the Ossewabrandwag (OB, the Ox-Wagon Sentinel) was the largest and most successful Afrikaner Nationalist organisation with pro-Nazi sympathies prior to and during the Second World War. The Ossewabrandwag was formed on the back of the 1938 Great Trek Centennial celebration – the centennial was planned under the directive of the “Afrikaner Broederbond” (Brotherhood) and championed by its Chairman, Henning Klopper. They sought to use the centenary anniversary of the 1828 Great Trek to unite the “Cape Afrikaners” and the “Boere Afrikaners” under the pioneering symbology of the Great Trek and to literally map a “path to a South African Republic” under a white Afrikaner hegemony. The trek re-enactment was very successful, and Klopper managed to realign white Afrikaner identity under the Broederbond’s Christian Nationalist ideology calling on providence and declaring it a ‘sacred happening’.21

The OB was tasked with spreading the Broederbond’s (and the PNP’s) ideology of Christian Nationalism like “wildfire” across the country (hence the name Ox wagon “Firewatch”’ or “Sentinel”). The OB’s national socialist leanings are seen in correlation with other world ideologies of the time, and specifically to that of Nazi Germany.22 Afrikaner Christian Nationalism, although grounded in “Krugerism” as an ideology, can be regarded as a derivative of German National Socialism and Italian Fascism and is identified as such by OB leaders like John Vorster in 1942.23 Earlier, the future leader of the OB, Dr Hans Van Rensburg, whilst a Union Defence Force officer, had met with Adolf Hitler and became an avowed admirer of both Hitler and Nazim. As leader of the OB, he then later infused the organisation with National Socialist ideology, whereafter the organisation took on a distinctive fascist appearance, with Nazi ritual, insignia, structure, oaths and salutes.

Ideologically speaking the OB adopted a number of Nazi characteristics: they opposed communism, and approved of antisemitism. The OB adopted the Nazi creed of “Blut und Boden” (Blood and Soil) in terms of both racial purity and an historical bond and rights to the land. They embraced the “Führer Principle” and the “anti-democratic” totalitarian state (rejecting “British” parliamentary democracy). They also used a derivative of the Nazi creed of “Kinder, Küche, Kirche” (Children, Kitchen, Church) as to the role of women and the role of the church in relation to state. In terms of economic policy, the OB also adopted a derivative of the Nazi German economic policy calling for the expropriation of “Jewish monopoly capital” without compensation and adding “British monopoly capital” to the mix.24

Although the OB never pitched itself as a National Socialist party, the OB is regarded as a Nazi-sympathising grouping.25 By the early 1940’s the OB gained its own militaristic wing, called the “Stormjaers”, who countered the South African war effort through sabotage of infrastructure, targeting Jewish businesses and assassinations. The OB during the war also directly aided the Nazi war efforts aimed at sedition, espionage, spy smuggling, and collecting intelligence in the Union. The post-war Barrett Commission investigation into South African renegades even contains a personal confession ‘van Rensburg vs. Rex’ as to van Rensburg’s regular and treasonous collaboration with Nazi Germany over a set period of time during the war.26

By July 1939, the Black-shirts were formally incorporated into the OB and focussed on the recruiting of “Christian minded National Aryans” into the OB infusing it with more National Socialist “volkisch” Nationalism. This took the OB well beyond its original intention of functioning as a wholesome cultural organ of Afrikanerdom and the National Party.27

The bedrock of Fascism and anti-Communism in Britain

Following the Great Depression in the early 1930s, the United Kingdom and Europe too saw a spike in support for the ideals of fascism. Initially small, these early British fascists pointed to the success of emerging autocracies in Italy and Germany. They saw this mode of fascism as a solution to the economic ramifications of the Great Depression. In Britain, Oswald Mosley was a popular Labour Party Member of Parliament and he brought what may have remained an insignificant fascist voice to prominence.28

During the early 1930s, Mosley became convinced that this new fascist ideology offered the way forward for economic and political reform. The severe economic and unemployment crisis caused by the Great Depression in Britain led Mosely to believe in a centralised political power based on a Keynesian economic state, yet with a broader emphasis on deficit spending and socialism.29

Mosley resigned from the Labour Party in early 1931. On 28 February 1931 he formed the “New Party” and, based on his memorandum of economic reforms, this party in turn became increasingly influenced by fascism. In January 1932, Mosley met with Benito Mussolini in Italy.30 Mosley wrote a new manifesto “The Greater Britain”, which inspired him to fold the New Party and form the British Union of Fascists (BUF), on 1 October 1932.31 By 1934, the BUF hit a very popular chord with a segment of the British public, and initially grew to around 40,000 members. Mosley had previously advocated for a corporate state, but rejected the essential Marxist tenet of class conflict and the BUF switched to an anti-Communist leaning.32 Mosely had also previously advocated that trade with the Soviet Union conflicted with his plans for a self-sufficient imperial economic system.33 The BUF followed the dictatorship principle, and Mosley’s system thus called for a powerful executive figure called “The Minister”.34 Mosley also adopted the Italian Fascist Corporate system, or “Corporativismo”, which allowed for capitalism, but where it failed, or worked against the state, then the state would intervene in economic production.35

However, his movement eventually became a haven for lunatic antisemites and far right-wing extremists from the fringes of British society. It was not Mosley’s carefully outlined fascist policies, nor his vision of an industrial and economic utopia, which came to represent the BUF. Instead, it was their reputation for violence and the forcible removal of hecklers at rallies by uniformed BUF strongmen also called “Black-shirts”. The general public began to perceive the BUF as little more than violent thugs on the fringe of society. By 1937 the BUF had further distanced itself from popular favour and moved from a benign, harmless curiosity, to a para-military menace. Mosley also increasingly embraced violent change and anti-Semitism. By the end of 1936, the general public associated the BUF and Mosley with German National Socialism and Hitler, and both he and the BUF became a hated national pariah on the fringe of British society.36

Such was the universal British hatred for Mosley’s movement on the home front that it initially turned the British public against Nazism and Fascism as ideologies, more so than Hitler or Mussolini. By the start of the Second World War in 1939, the BUF membership declined to about 20,000 members.37

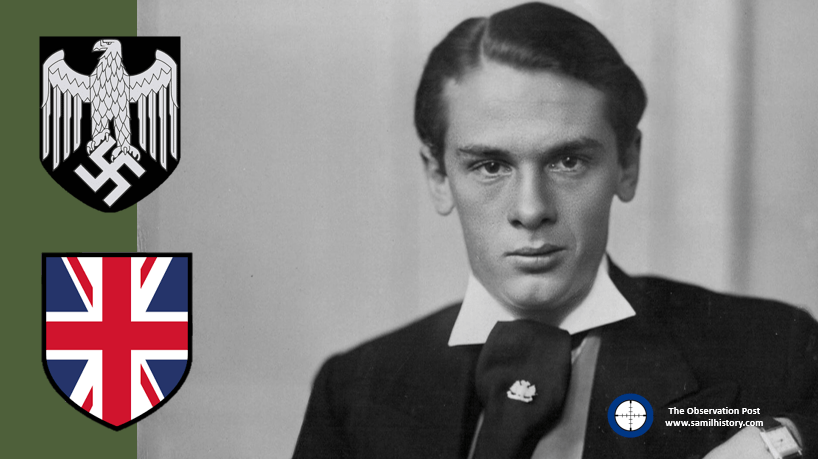

Although Fascism was a fringe ideology in the United Kingdom, other Britons were also romanced by German National Socialism and Italian Fascism, the most significant individuals here are John Amery, Eric Pleasants, and William Brooke Joyce. American born Joyce was a member of the BUF whilst he lived in Britain, and later would infamously became known as ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ – a propagandist broadcasting from Nazi Germany during the war. All three would play a key role in the future “British Free Corps” (BFC) of the Waffen SS.

Road to War

In South Africa and in the United Kingdom this fierce polarisation over Nazi Germany came to a head when Britain and France declared war against Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939. In Britain the activities of fringe fascists were relatively easily curtailed when on the 23 May 1940, Mosley and 740 other BUF members were interned under the Defence Regulation 18B. On 10 July 1940, the organisation was declared unlawful, whereupon it ceased to exist with no real resistance.

The South African case was an entirely different matter. The polarisation over Nazism and Germany was especially felt in the Afrikaner Nationalist community who, through the various neo-Nazi movements in the Union described above, had become enamoured and invested in Nazi Germany. When Britain declared war on Germany, the United Party found itself in a dilemma and a parliamentary three-way debate would take place almost immediately after Britain’s’ declaration. This debate, primarily between the two factions in the United Party (Hertzog’s cabal and Smut’s cabal) and the Purified Nationalists, was whether South Africa should go to war against Germany or remain neutral. As the United Party was loaded with Hertzog’s Nationalists, and there was also Malan’s Nationalists in opposition, Prime Minister Hertzog was very confident he had the majority to carry a motion of neutrality.

Hertzog would argue in his speech that Hitler’s invasion of Poland, and annexations of Austria and Czechoslovakia, was not an indication that the German leader aspired to world conquest, and that the Afrikaners well understood Germany’s right to struggle for their own self-determination against the hostility of the outside world. He also argued that Germany’s actions constituted no threat to South African security whatsoever, and that a policy of neutrality under these circumstances was the only logical policy to adopt. General Smuts would reply in his speech that since the fate of South West Africa would depend on the outcome of the war, South Africa’s interests were virtually involved. Furthermore, South Africa was part of the British Commonwealth whose fate now hung in the balance. To stand aside from the conflict would be to expose the whole “civilised” world to danger.38 Smuts’ amendment to Hertzog’s Motion of Neutrality was carried by 80 votes to 67 votes on the 4 September 1939, and as a result South Africa thus found itself at war against Nazi Germany. Surprised at the outcome, Hertzog promptly resigned and along with 36 of his supporters left the United Party, thereby leaving the South African Premiership and the leadership of the United Party to Smuts.39 The Union officially declared war on Nazi Germany on 6 September 1939.40 Later, on 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on France and Britain, and in response as an Allied country, South Africa declared war on Italy the next day.41

Hertzog moved to form a new party – the “Volksparty” and successfully reconciled with the “Malanites” in the PNP to then form the “Herenigde Nasionale Volksparty” (HNP)42 or Reunited National Party. However, on 5 November 1940 at the HNP’s Convention in Bloemfontein, Hertzog reaffirmed his position on English-speakers rights, and falling on deaf ears, he grabbed his hat and walked out of the National Party forever. In retirement and angered by his treatment at the hands of HNP and Malan, he performed a remarkable volte-face and issued a press release in October 1941 in which he championed National Socialism.43 In the release Hertzog excoriated “liberal capitalism” and the democratic party system, praised National Socialism as in keeping with the traditions of the Afrikaner, and argued that South Africa needed the oversight of a one-party state dictatorship.44

As happened in the United Kingdom, the Union instituted emergency regulations to the curtail Nazi sympathetic organisations and their leaders during the war – even imprisoning some. However unlike in Britain, this was met with home grown resistance in South Africa when pro-Nazi organisations like the SANP and OB moved into active and direct support of both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy’s war efforts. They did this either through espionage, sedition, or through armed actions and sabotage. On the political stage the HNP continued with its neutrality position whilst at the same time it tacitly supported Nazi Germany.

Approach to Recruitment – South Africa, Britain and Germany

With war declared, in South Africa attention was given to recruiting and bolstering South Africa’s statutory forces, which were undercapitalised and under resourced by the National Party during the inter-war years. On 14 March 1940, Smuts forced Pirow out of his position as Minister of Defence for mismanaging his parliamentary portfolio and his failed “bush cart strategy”.45 Smuts concluded that the re-bolstering and recruitment of the Union Defence Force (UDF) had to be done using volunteerism and not conscription – especially given the sensitivities of Afrikaners to both Germany and Great Britain. Using this strategy, Smuts was able to ultimately call up nearly a quarter of the white adult population for voluntary wartime service – half of which were Afrikaners. Their motivations and political dispositions for joining the Union’s war effort varied considerably. Some held indifferent views as to National Socialism, many held strong views as to anti-Communism, and many joined solely for economic reasons – mainly employment given the ‘poor white’ problem which had historically hobbled the white Afrikaans speaking community.46

With war declared, in Britain the process of recruitment was somewhat different to South Africa. As with South Africa, the inter-war period and austerity measures had left Britain’s armed forces woefully unfit for purpose. Consequently, on 3 September 1939, Britain immediately turned to conscription. The day Britain declared war on Germany, Parliament passed The National Service (Armed Forces) Act and imposed conscription on all males aged between 18 and 41,47 regardless of their political affiliations and/or dispositions to Nazism, Fascism, or Communism.

With war declared and as the war progressed, Germany’s approach to resourcing its armed forces was also somewhat different. Conscription into military service into the statutory German armed forces (Wehrmacht) had begun as early as 16 March 1935, and it initially applied to all German men of “Aryan”’ classification aged between 18 and 45.

In parallel to the Wehrmacht, the Schutzstaffel (SS) was born under the leadership of Heinrich Himmler, and was essentially a police force and not a military one. One arm of the SS, the SS Verfugungstruppe (SSVT), emerged as a paramilitary wing and, on 17 August 1938, prior to the infamous “Kristallnacht”, Hitler decreed that the SSVT was not purely that of a police force, nor of an army unit. Rather, it was a National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazi Party) political unit at his personal disposal.48 The SSVT would be the forerunner of the Waffen SS when it began to take on an increasingly military guise. On 19 August 1939, just before the invasion of Poland, on an order from Hitler, the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), placed the SSVT under the commander-in-chief of the Army (Heer) to fight alongside the Wehrmacht.49

The formation of the Waffen SS and the British Free Corps

Broadly speaking, once the war was underway the SS had evolved into three groups – the Allgemeine SS (General SS), which was a general police force also enforcing Nazi racial policy; the Waffen SS, which consisted of militarised combat units with special allegiance to Hitler and the Nazi Party; and finally, the SS Totenkopf (Death Head) units that were in charge of concentration camps and the extermination of Jews and other undesirables according to Nazi philosophy.

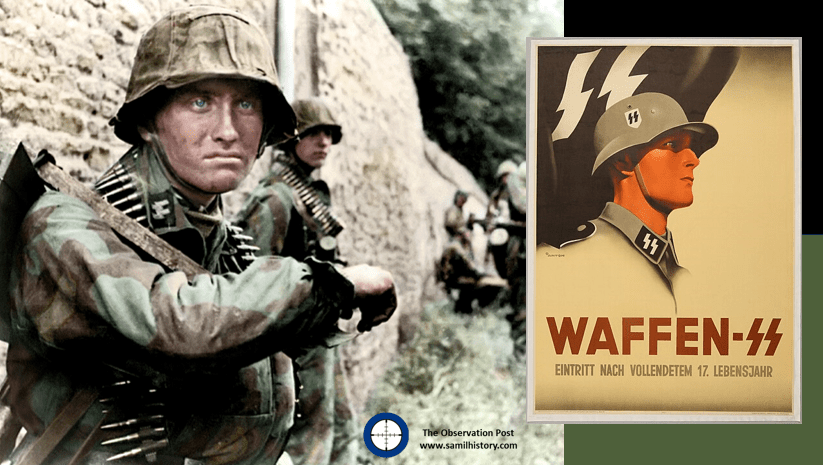

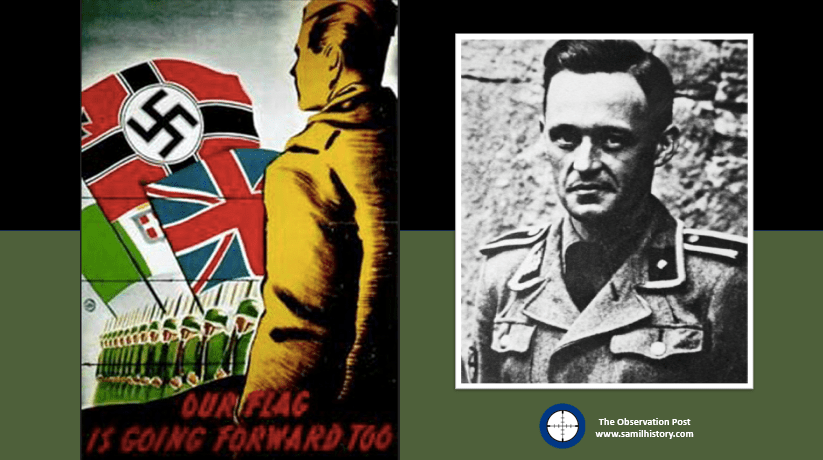

The Waffen SS would grow from just 3 Regiments to a mammoth para-military army with 22 Corps, just over 38 Divisions, 16 Brigades and about 14 Foreign Legions during course of the war. Initially recruitment was limited to ethnic Germans of “Aryan ancestry”. Yet this was relaxed from 1940, and then widened again after Operation Barbarossa was launched in June 1941. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Waffen SS was pitched as a crusade against the onset of Bolshevism (Communism in effect). More foreign volunteers, and even eventually foreign conscripts, were raised from occupied countries and/or countries deemed as having population demographics which met with Nazi Aryan dogma. Many of these foreign national volunteers and conscripts joined the various ethically and culturally differentiated Waffen SS structures.

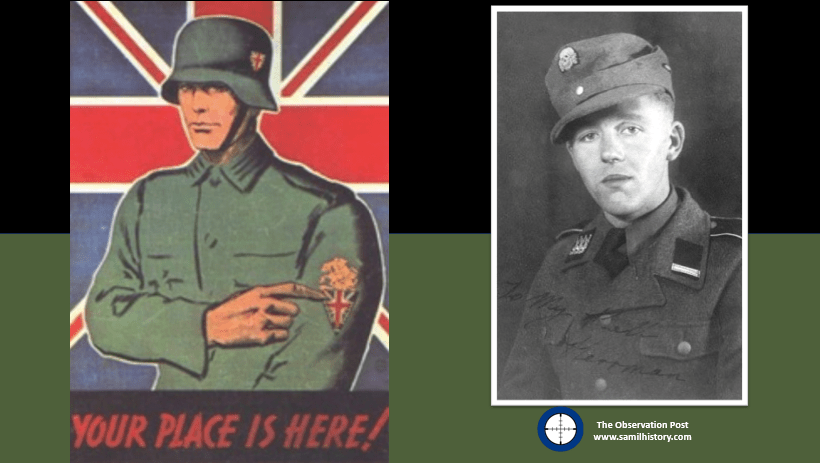

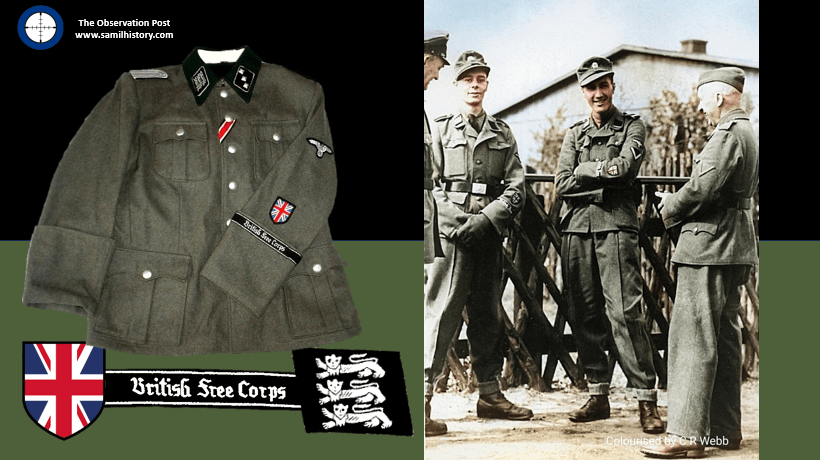

One such Waffen SS unit focussed on British Commonwealth and Allied volunteers who displayed a positive disposition to National Socialism and anti-bolshevism, and met the Nazi “Aryan” recruitment ideals. The unit was originally conceived as the “Legion of St George” by John Amery. Amery was born into the British political elite, the son of Leo Amery, and older brother of Julian Amery, both of whom served as Tory (Conservative) Ministers of Parliament. John Amery was considered a troubled and difficult youngster and became a committed fascist and staunch anti-Communist. Moving to France after he was bankrupted, he was reputed to have joined Franco’s Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War in 1936, eventually returning to France, and was there when Germany occupied France in June 1940.50

John Amery travelled to Berlin in October 1942 and proposed to the “German English Committee” the formation of a British volunteer force to help fight bolshevism. Remaining in Germany, Amery made a series of pro-German and anti-Communist propaganda radio broadcasts to British listeners. After meeting Jacques Doriot in January 1943, Amery modelled his concept on the “Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism” – a German Wehrmacht unit consisting of French collaborators. Called the “Legion of St George”, Amery released a proclamation primarily targeting British and Commonwealth prisoners of war (POW), from which cohort he aimed to recruit about 100 members.

In his proclamation Amery appealed to these POWs and warned that their wives and children at home are menaced by the invasion of the “Hordes of Bolshevik Barbarity” and the “Dragon of Asiatic and Jewish Bestiality”. He urged these POWs to join the Legion of St George to fight on the German-Finnish front alongside the German and Finnish people against the Soviet Union. He issued a mistruth, stating that hundreds of their countrymen had already joined his legion for the purposes of upholding the British Empire.51

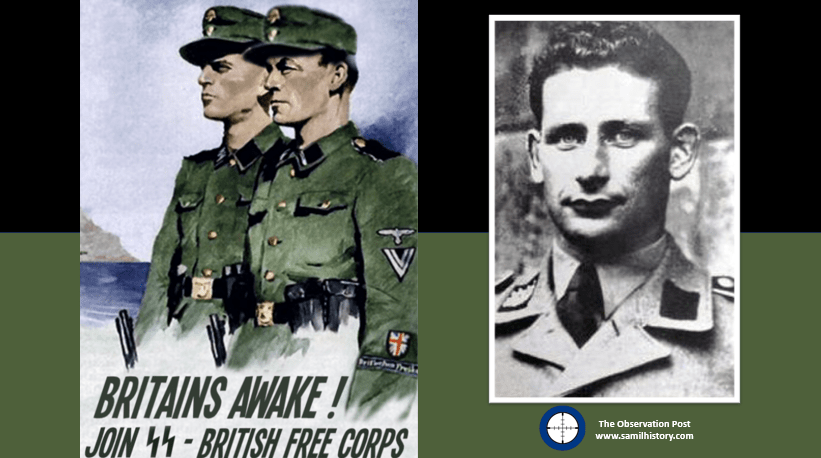

Amery’s recruiting drive, despite persistence, did not yield the hundreds of volunteers as he had hoped, as his message simply did not resonate with the British, Commonwealth and Allied prisoners. However, he managed to prick the interest of a handful of POWs, notably Kenneth Berry – a young and impressionable British merchant mariner and William Charles Brittain, a British Royal Warwickshire Regiment member, captured in Crete in 1941. The first POW recruits were accommodated at what was pitched as a “holiday camp” in Genshagen, Berlin in August 1943.52 By November 1943, they were moved to a requisitioned café in the Pankow district of Berlin.53 Amery’s link to the unit ended in October 1943, after the Waffen SS decided they did not need his services. The unit subsequently officially become a military unit of the Waffen SS on 1 January 1944, and was re-named the “British Free Corps” (BFC).54

In addition to Amery, it is also noted that the infamous BUF stalwart, the American born Joyce was also in Germany at this time. He, like Amery, was also involved in Nazi propaganda radio broadcasts. Joyce and his wife Margaret became German citizens on 26 September 1940, and his reach expanded with script writing for a trio of stations: Radio Caledonia, Workers’ Challenge, and the New British Broadcasting Service. He also helped write propaganda to assist in the recruitment British POWs to enlist in the BFC and published a book, “Twilight Over England”, in which he contrasted the ideal of Nazi Germany versus the Jewish-dominated, capitalist enemy state.55

Resourcing the BFC

The first Commander of the BFC was Hauptsturmfurer SS Hans Werner Roepke, an English-speaking German.56 Continuing to recruit British and Commonwealth POWs to the BFC, the unit was equipped and repeatedly moved between Hanover and Dresden, and by 8 March 1945 they were billeted near Berlin.57 From its conception to the end of the war, a period of nearly fifteen months, the BUF could account on only 39 people who ultimately served in it.58

Initially only six men joined the BFC, and they became known as the “Big 6”: Thomas Cooper,59 a British born member of Mosley’s BUF with a German mother. He joined the Waffen SS as a Volksdeutsche (a foreign national with German heritage) and transferred to the BFC. Roy Courlander,60 a Lance Corporal with strong anti-Communist leanings serving with the New Zealand Armed Forces in their Intelligence Corps prior to his capture. Before joining the BFC, he was involved in broadcasting Nazi propaganda to his countrymen. Edwin Martin,61 a Private in the Canadian Army, who served in the Essex Scottish Regiment prior to his capture. Frank McLardy,62 another member of Mosley’s BUF and a Sergeant the Royal Army Medical Corps prior to capture. Alfred Minchin,63 a captured British merchant mariner who is accredited with selecting the name of the BFC.64 Finally, John Wilson, a British trooper serving with the Royal Marines No. 3 Commando prior to his capture.65

By February 1944, the BFC boasted only eight members, however, soon thereafter more recruitment of Allied POW took place and Robert Heights (British), Robert Lane (British), Norman Rose (British), Lionel Wood (Australian) and Thomas Freeman (British) joined the unit. Freeman, also a BUF member prior to the war, did so to sabotage the project. Freeman and Wilson recruited two Australians, Robert Chipchase and Albert Stokes, and then Theo Ellsmore – a Belgian who masqueraded as a South African. Chipchase only spent a couple of days in the BFC. Stokes was Freeman’s friend and he also initially intended to sabotage the project.66

Leading up to June 1944, William How (British), Ernest Nichols (British), Herbert Rowlands (British) – he had also been a BUF member before the war, and Roland Barker (an Australian, regarded as man of limited intelligence) all joined the BFC. In June two Britons, John Leister and Eric Pleasants (another former BUF member) joined the unit – both were convicted thieves serving time in France in a merchant navy POW camp.67

Other POW recruits over this period included Harry Dean Bachelor (British), Hugh Cowie (British), Roy Futcher (British), Frank Maton (British, also a BUF member before the war) and Tom Perkins – of this group only Maton stood out for his pro-Nazi convictions. In June 1944 the BFC total compliment reached 27 men.68

In June 1944, and after the D-Day landings and the commencement of Operation Overlord, the BFC was marred by mutiny. Freeman, Courlander, Maton, and Rowlands all escaped from the unit. Other members returned to and/or requested to be transferred back to the POW camps. Some of the troublesome members were transferred to isolation and labour camps. Some members joining the BFC complained about being blackmailed into it, while others were identified as being mentally unstable.69 A stable, conformist and homogeneous military unit, the BFC was not.

Enter the South Africans

By November 1944 the BFC stabilised somewhat, and some members even returned to it from their respective POW camps. During the summer of 1944/1945 new members started to arrive, and of importance at this time was a trio of South African Prisoners of War – Pieter Labuschagne, Lawrence Viljoen, and, of specific importance is Mardon, a South African with fierce Russophobia, attributed to the contact he had with Russian POWs.70 By the end of January 1945, the BFC reached its zenith in terms of numbers on the ground – 27 members,71 which is only about the size of a single platoon.

Other South Africans have been involved in the recruiting of BFC members, these include Sgt. F.W. Lochrenburg, Gnr B.J.F Brandsma and Pte. S.P.J. van Dyk, however they do not join the BFC and are instead used by the German and BFC authorities as stool pigeons to lure recruits to the BFC.

On the three South Africans that do join the BFC, all come from varying backgrounds:

Douglas Mardon was born in Durban on 22 May 1919, he’s of British heritage. He saw service as member of 2nd Transvaal Scottish and when war broke out he attested with the 1st Battalion of the Royal Durban Light Infantry in 1940, having had attained the rank of Lance Corporal. He is in North Africa fighting for his unit when he is captured during the Battle of Gazala on 6 June 1942. Initially in a POW camp in Italy and thereafter he is transferred to Museburg in Austria – it was here that he made contact with Russian POW whom he learned to detest. He was moved to Stalag 8B and discovered a pamphlet for the BFC inserted into a packet of cigarettes and it perked his interest in joining the BFC.72

Labuschagne is born 4 January 1922, of Afrikaans heritage from Zastron and attests with the President Steyn Regiment (later with Louw Wepener Regiment). Captured on 23 November 1941 at the Battle of Sidi Rezegh in North Africa. Initially in a POW camp in Italy, he is later transferred to Germany. He learns about the BFC from a distributed pamphlet which is left on his bed.73

Viljoen was listed as a Constable and attests as a Private in the 1st South African Police Battalion, Afrikaans by heritage, born on 19 June 1917. Viljoen is from Laingsburg and later lives in Worcester in the Western Cape.74

Mardon on 8 March 1945 received a promotion to Unterscharführer and was given command of a section of the BFC, the other two are given the rank of ‘SS Mann’ (the equivalent of a private).

On 13 February 1945, whilst the BFC was billeted in Dresden on their way to the Eastern Front, now outside Berlin, the city came under air attack by Allied bombers – during this attack Viljoen disappeared. His colleagues thought he was dead, but this turned out not to be the case.75

BFC Combat deployment

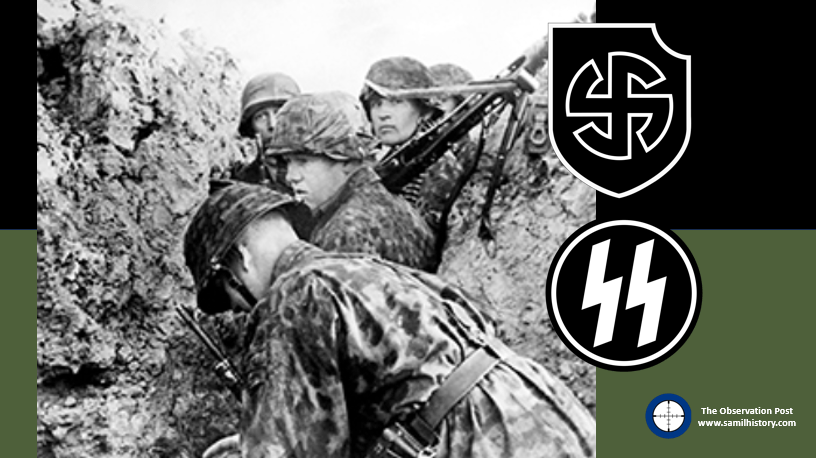

By March 1945, the BFC was deployed to Berlin for combat. At this stage, some of its members had already started to have second thoughts on the prospect of fighting a losing battle, which prompted some members to request to be returned to their POW camps or transferred to other non-combat units. With a corium of committed BFC members having volunteered to fight Communism on 15 March 1945 the BFC was deployed to Berlin and billeted on the eastern front alongside the III (Germanisches) SS-Panzer Korps. Under-resourced, they are not formally given ammunition, the BFC use initiative and secure limited stocks of ammunition.76

On 22 March 1945, the BFC was ordered to reinforce a reconnaissance battalion of the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland, which was regarded as one of the most multicultural divisions in the Waffen SS. The 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland was commanded by Brigadefürer Joachim Ziegler and fell under the III (Germanisches) SS Panzer Corps under the overall command of Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner.

Only one BFC combat engagement is found in contemporary accounts, and it is unclear as to the full role of the BFC. On 22 March whilst the BFC section under Mardon’s command was entrenching itself alongside the 3rd Company of SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 11 “Nordland” – the reconnaissance battalion it was attached to. They were now situated in the village of Schoenburg near the west bank of the Oder Canal.77 This 3rd Company of the SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 11 “Nordland” was partially overrun by an advance element of the Red Army who had blundered onto its position by accident. Although taken by surprise, the Waffen SS troopers launched a spirited counterattack driving off the Soviets. It is however unclear if any BFC members were involved in the fight and to what extent, as interviews with BFC members after the war point to minimal if any involvement in actual combat (although this reasoning was also used by BFC members as an excuse to evade charges of treason), according to court statements they were located in the second trench line behind the primary line on the Oder canal, and the second trench line never came under attack by the Red Army.78

Whilst the BFC was entrenched outside Schoenburg with the 3rd Company of the SS-Panzer-Aufklärungs-Abteilung 11 “Nordland”, Cooper managed to convince the Division’s Commander, Brigadefurer Joachim Ziegler, that the BFC was indeed unfit for combat and it was withdrawn from the line and sent to Tempin 79 on 16 April 1945 to join the transport company of Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner’s Headquarters staff (Kraftfahrstaffel StabSteiner).80 The BFC moved with the transport company to Neustrelitz whereupon on 29 April 1945 Obergruppenführer Steiner orders his Panzer Corps to break contact with the Soviets and to head west into Anglo-American captivity. By 2 May 1945, Cooper and the remnants of the BFC surrendered to the 121st Infantry Regiment of the United States of America near Schwerin.81

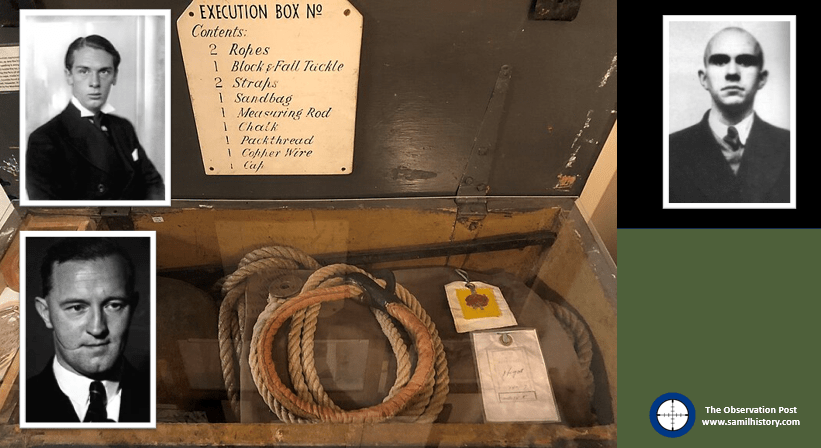

After the war ended, numerous commissions were instituted by the British and the Commonwealth countries to round up and interrogate all their nationals who aided any of the Axis powers by any means during the war. Those accused of High Treason were brought to justice. In the case of those who had joined the Waffen SS, and specifically those having joined or were associated to the BFC, the sentences and outcomes varied from acquittal, to time served, to fines, to various degrees of incarceration and hard labour, and even capital punishment. The gallows were a fate awaiting Amery, who hanged on 19 December 1945, as well as Joyce, who hanged on 3 January 1946, Cooper was also given the death sentence, but his execution was stayed at the last minute on 20 February 194682 and commuted to life in prison.

In the end they all fall onto the “wrong” side of history, and can be best summed up by John Amery’s epitaph written by his father Leo Amery (who by co-incidence also penned the Times history of the South African War 1899-1902):

‘At end of wayward days he found a cause – ’Twas not his Country’s – Only time can tell if that defiance of our ancient laws was as treason or foreknowledge. He sleeps well.‘

Communism – not our creed

As in Britain, in South Africa at the start of the war Communism is perfectly legal. It is however regarded with disdain by moderate and right wing white South Africans, however it does find a home in some white supporters of the Labour Party and in the small community of Jewish immigrants who are highly unionised (especially in the garment industry) and have liberal leanings. White South Africans in general are in support of the United Party and fearful of Communism and its growing support amongst aspirant and politicised Black South Africans.

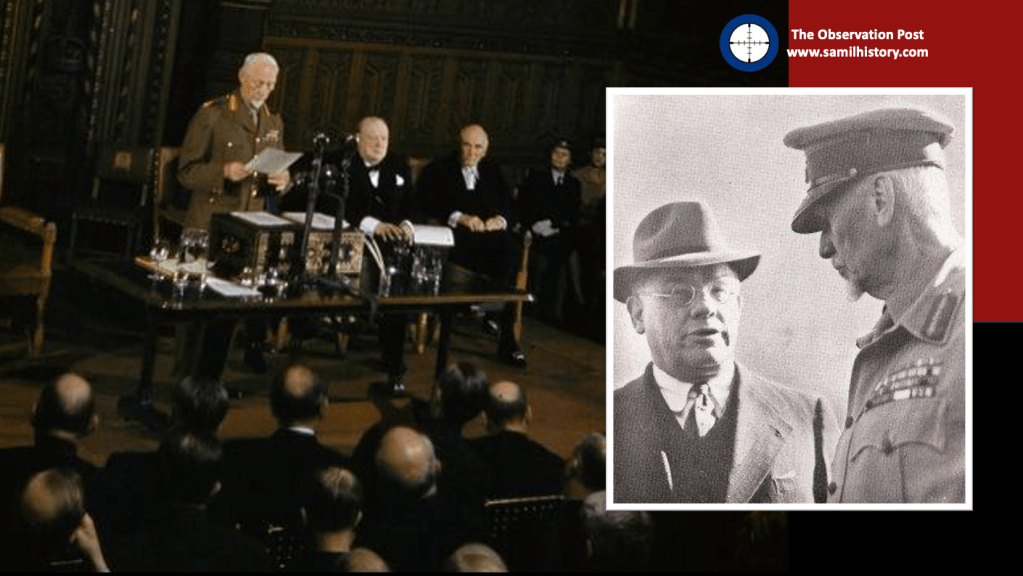

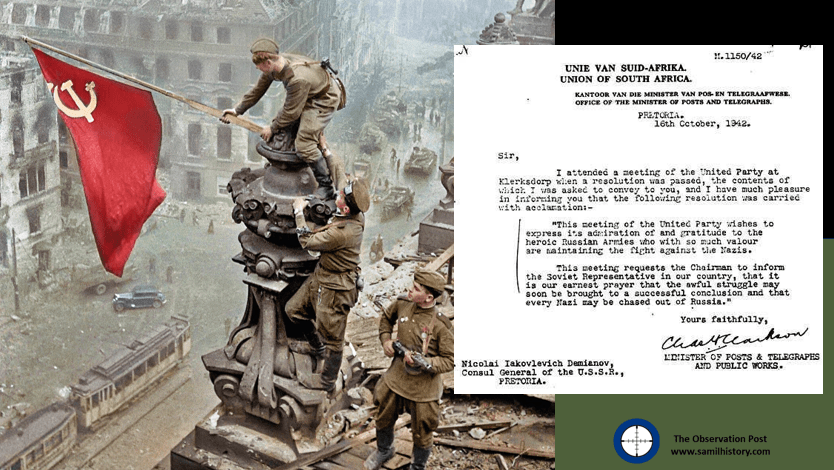

As to the fear of Communism, the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany on 22 June 1941 causing the Soviet Union to side with the Allies proves a problematic and awkward question in South Africa. The ruling party, the United Party, as well as its primary opposition party, the Reformed National Party – are all principally anti-communist, in fact they are very vocally anti-Communist. General Jan Smuts would try and give reason to his and his country’s own anti-Communist sentiments and siding alongside the Soviet Union in July 1941 when he said:

‘Nobody can say we are now league with the Communists and fighting the battles of Communism. More fitly can the neutralists and the fence sitters be charged with fighting the battle of Nazism. If Hitler has driven Russia to fight in self-defence, we bless her all success, without for a moment identifying ourselves with her Communistic creed. Hitler has made Russia his enemy and not made us friendly to her creed’.83

What remains a truism throughout the war, is that although Communism is an anathema to the United Kingdom, United States and the South African Union’s mainstream and right wing politics, the Soviet Union remains a key supported ally, and inside South Africa the Red Cross raises support for the Soviet Union and Smuts’ United Party even expresses solidarity with the Soviet Union after a meeting held on 16 October 1942 and they notify the Consul General of the USSR in Pretoria of their unwavering support.84

South African Renegades – The Rein and Barrett Missions

After the end of the Second World War, all the Allied nations embarked on a Nazi hunt to prosecute war criminals. This included high profile war crimes, but it also included hunting all nationals who, by siding with Nazi Germany and the Axis forces, had committed an act of High Treason. South Africa’s post war hunt for its nationals assisting or joining Nazi Germany and other Axis forces remained relatively undocumented and under-researched, however this does not mean that South Africa did nothing to find and prosecute its war criminals.85

In December 1945, it was agreed that those South Africans who had committed treason as Union nationals, would be dealt with by the Department of Justice, whereas those who qualified as ex-Union Prisoners of War who joined German forces would be dealt with by the Union Defence Forces’ Military Disciplinarian Code.86 In February 1946 the Rein Mission left for Europe to work alongside British MI5 to identify South African War criminals, this opened the way to a more comprehensive mission, called the Barrett Mission aimed primarily at South Africans who whether directly or indirectly aided the German War effort.87 These South Africans were referred to by historian Ian van der Waag as ‘Hitler’s Springboks’ and they included Radio Zeesen Afrikaner broadcasters, stool pigeons, collaborators and members of the Waffen SS (and BFC).88

‘Hitler’s Springboks’ then constituted a small number of South African citizens in Nazi Germany who were swept up by Allied forces, having either caught up with them through various interrogations or them having surrendered to Allied Forces directly. Previously embargoed or restricted archival material, now in the Department of Justice archives indicates that by 21 July 1945 the Department of Military Intelligence of the Union Defence Force started formulating lists of South African Union Nationals in Nazi Germany during wartime and requesting the British MI5 Intelligence Service to supply more information on them and that they had to hold them for interrogation. These primarily included name lists of South African Nationals or German Nationals with South African heritage or background who had in some way played a role in influencing South African Prisoners of War (POW) in various POW camps in Germany. This was achieved either through propaganda, through printed media, and/or radio broadcasting with the expressed purposes of forwarding Nazi German war aims and trying to influence them to join Germany’s armed forces.89

Of interest here are the various Afrikaner broadcasters of Radio Zeesen, Eric Holm, Johannes Snoek, Michael Pienaar, Francois Schaefer, Betty Blackburn (Marshall), Isa Goos, Danie Michell, and Marjorie Sanna (Hofmeyr), along with three German academics with South African backgrounds – Onderfuehrer Becker, Professor Bruxmer and Captain Brauer who play a key role in trying to influence South African POWs at various POW camps in Germany. Also swept up in this request to MI5 are a handful South African Nationals with German heritage (Volksdeutsche) who had been in Germany at the start of the war and had joined standard German Wehrmacht units, notably Carl Johannes Hugo and Konrad Rust.90

The Justice Department meets on 19 March 1946 at the Ministry of Justice (including Barrett), whereby a decision is taken to issue Police dockets and prosecute through the Ministry all identified ‘High Treason’ Union Defence Force renegades who had served in German Armed Forces. Those Union renegades identified with lessor infractions of the military code of conduct would be prosecuted by the Union Defence Force.91

The Rein Mission and MI5 British Intelligence had forwarded their initial findings on South African Union renegades in BFC to the Union from their preliminary investigations to the South African Union’s Justice Department – these include 62 sworn affidavits and 53 police statements from 166 interviews to the Rein Mission.92 Identified British Free Corps (BFC) South African Union nationals who qualified as renegades having potentially committed High Treaso, they are – L/Cpl D.C. Mardon, Pte P.A.H. Labuschagne and Pte L.M. Viljoen.93

Other South African Union Defence Force (UDF) members are identified as having joined or having been recruited to the BFC, of these the notable members are; Sgt. F.W. Lochrenburg, Gnr B.J.F Brandsma and Pte. S.P.J. van Dyk, however the initial investigations indicate they acted as stool pigeons94 – In addition, the chaotic nature of the BFC, and their short flirtations with it, there is insufficient evidence. This compels the Justice Department to believe there is an insufficient case for High Treason and they leave their cases to the UDF to investigate under their disciplinary code.95

By 4 July 1946, the case against South African nationals who had been recruited and/or joined the British Free Corps (BFC) of the Waffen SS had been fully reviewed by the Barrett Mission. Mr. L.C. Barrett, acting as the Senior Professional Assistant for the Attorney General in Pretoria issues a relatively comprehensive report on the BFC, outlining its history and intent, the grounding of the founders in British Fascism, its recruitment procedures, leadership, and deployment. These findings gleaned primarily from British Intelligence and confessions of BFC members in the United Kingdom who had already been interrogated. On the issue of South African Union Defence Force members who had served in the BFC or had been stool-pigeons in the recruitment process for the BFC, he concludes that there is a certainly a case to be made of high treason for Mardon, Labuschagne and Viljoen back in the South African Union.96

On Trial for High Treason

After Mardon, Labuschagne and Viljoen were arrested and repatriated back to South Africa a decision had to made as to how the charges and trials against them would proceed, especially in light of the unique socio-political landscape in South Africa and Prime Minister Jan Smuts’ continual reconciliation and appeasement of the Afrikaner right in order to establish ‘racial harmony’ and reconciliation, an approach he had taken to this demographic which had its roots going back even as far back as the 1914 Maritz Revolt.97 An approach which had not changed much by the end of World War 2 given Smuts’ cautious approach taken to political opponents who had flirted with Nazism like Hans van Rensburg, the Commandant General of the Ossewabrandwag and the ever increasing case of high treason stacking up against him, so much so that ‘van Rensburg was indeed guilty of high treason’.98

In addition Smuts had taken a lenient approach to Robey Leibrandt, the leader of the National Socialist Rebels whose death sentence for high treason he commuted to life in prison instead, the underpinning reason – he had fought alongside Leibrandt’s father during the South African War (1899-1902, seeking harmony instead with this highly disgruntled anti-British demographic of Afrikanerdom.99

Given this background, the decision was taken to prosecute all renegade cases of high treason using a special court.

The charges against Mardon, Labuschagne and Viljoen broadly covered three areas of High Treason Firstly, that whilst members of the South African state’s statute forces, they joined the statute forces of the German state, whilst South Africa was in a state of war against Germany (the enemy). Secondly that they joined military structures controlled by the enemy German state. Thirdly that they wore the uniform of the enemy German State. Fourthly that they underwent military training offered by the enemy German State. Fifthly, they bore arms against an allied state of the Union of South Africa.100

Mardon in his defence insisted that his sole motivation was to fight against Bolshevism (Communism), which he saw as a threat to his homeland in South Africa as it would bring with it “black domination”. He also claimed he did not take the oath of allegiance to Nazi Germany and Hitler. The crown found that regardless, he had displayed “hostile intent” to both the Union of South Africa and her Allies by taking up arms and donning a German uniform – albeit with some adaptions showing a Union Flag on the sleeve and the British lions on the collar instead of the usual Waffen SS lightening bolts. The court did take into account that it was Mardon’s wish to only fight Communism and he wished no harm on his countryman and that he was true to this conviction having been assured by his German handlers that this was the sole purpose of his recruitment into the Waffen SS. As to anything unclear to what constituted ‘high treason’ the court found that any act which was designed to assist the enemy:

‘positively by giving help of any kind, or negatively by obstructing or weakening forces arrayed against (the enemy), is an act of high treason’. 101

In this key respect to this Mardon is found guilty of High Treason.

Oswald Pirow is one of the members of the renegades defence council, he applies for postponement of the verdict and withdraws when its refused. Barrett acts for the crown. The verdict is announced on 14 April 1947. On the charge of High Treason: Mardon is found guilty, he is given a fine of £75 or 9 months in prison.

In handing down a light sentence, Justice Ramsbottom finds mitigating factors in Mardon’s intentions to only fight against Communism and not the Union in his age and cites naivety of youth, he also considers the Prisoner of War position and the lack of uncensored ‘news’ available to persons in a POW camp and they been susceptible to enemy propaganda. Furthermore, he finds mitigation in the fact that the South African renegades only join the BFC late in the war, when the advancing Red Army is a well established fact, and their intentions were only to fight communism. Mardon’s time in prison of 3 months to date is also factored and the Judge looks to the case of another BFC member Kenneth Berry who is given a 9 months sentence by a British court as an appropriate benchmark for his verdict.

Noted here, Kenneth Berry’s case is a little unique in that does not advance in rank in the BFC and remains a ‘SS Man’ (a private) whereas Mardon is made a non-commissioned officer – a Unterscharführer and was given command of a section (10 men of the BFC). Berry receives what was considered at the time by Rebecca West to be the ‘lightest sentence conferred on any traitor’102 in the United Kingdom on account of his age. Berry is regarded by the Director of Public Prosecutions ‘as an irresponsible youth who was easily led.’103

Kenneth Berry has served his sentence by the time Mardon, Labuschagne and Viljoen are brought to trial, and he is brought to South Africa as a witness in their case, so too is William John Miller, another BFC member (British) who was a Royal Artillery Gunner prior to his capture – he was deemed so “useless” that Mardon refused to deploy him in a combat role.104 Harry Dean Batchelor, a British Royal Engineers sapper who joined the BFC also appears as a witness, so too does a German, Wilhelm August ‘Bob’ Rössler, a German Heer signaler, wounded he is attached to the BFC as an interpreter as his English was very good.105

Of interest is Kenneth Berry as a very wayward young man, he is positively disposed to the British Union of Fascists and John Amery, and even writes to Amery to give him a progress on how he is doing in the BFC and enjoying it.106 Berry spends much of his testimony on the difference between the German “Heer” (Statutory Army) and the Waffen SS, in addition to the differences in BFC insignia and that of other Waffen SS units.

In fact during the case, the issue of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) surfaces as there are so many members of the BFC who were BUF members – so much so it starts to take a strong BUF disposition and the unit’s leadership has to make it clear that it is not a ‘fascist’ undertaking but an anti-Communist undertaking so as to attract non-fascist and non-BUF British and Commonwealth Prisoners of War.107

Labuschagne’s charges follow the same as Mardon’s and he found guilty of High Treason on exactly the same terms as Mardon – that he joined an organisation controlled by the enemy (the BFC) for the purposes of fighting against the Soviet Union – an Ally of South Africa, that he was deployed in service of the enemy, that he donned the enemy’s uniform and that he underwent military training whilst in service of the enemy. In addition, Labuschagne is also found to have actively tried to recruit other South African Union POW to join the BFC. In all the court also concludes ‘hostile intent’. One difference is that Labuschagne at times uses the alias “Smith” however the court concludes that whilst this could be seen as a sinister move to cover his tracks, they also accept that he uses the alias as many of his British counterparts could not pronounce his surname.108

One key mitigating factor is brought up in Labuschagne’s case, when the BFC unit is been prepared for deployment to fight on the Berlin front, all the BFC members are called in and informed whether they have been selected to go, and although all of them have volunteered to go, Labuschagne is informed he has to stay behind at the base. The reason cited for this is Labuschagne is unliked by the men, especially Mardon who does not rate him and finds him to be a disrupter – so for the sake of maintaining a positive esprit de corps Labuschagne is removed from the line.109

Labuschagne’s is found guilty of High Treason, and his verdict is also announced on 14 April 1947. Like Mardon his sentence is also very light, and its in fact lighter than Mardon’s sentence – Labuschagne is given a fine of £40 or 4 months in prison.

Viljoen’s charges follow the same outline as Mardon and Labuschagne – that he joined an organisation controlled by the enemy (the BFC) for the purposes of fighting against the Soviet Union – an Ally of South Africa, that he was deployed in service of the enemy, that he donned the enemy’s uniform and that he underwent military training whilst in service of the enemy. Viljoen is however found to have absconded from the BFC during the Dresden Air Raid and was never really operationally deployed. His verdict, his charges are withdrawn and he’s acquitted.

The Oswalds

Of importance in also understanding the socio-political context of the treason trials of Mardon, Labuschagne and Viljoen, and that of other South African renegades, is the political disposition of their defence council. Oswald Pirow in almost all instances of the renegade defences acts as legal counsel, and Pirow has a special relationship with Oswald Mosley.

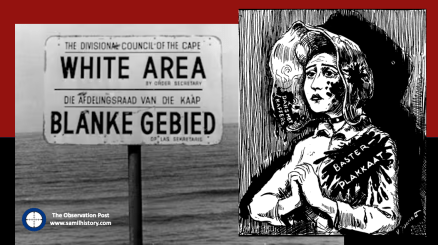

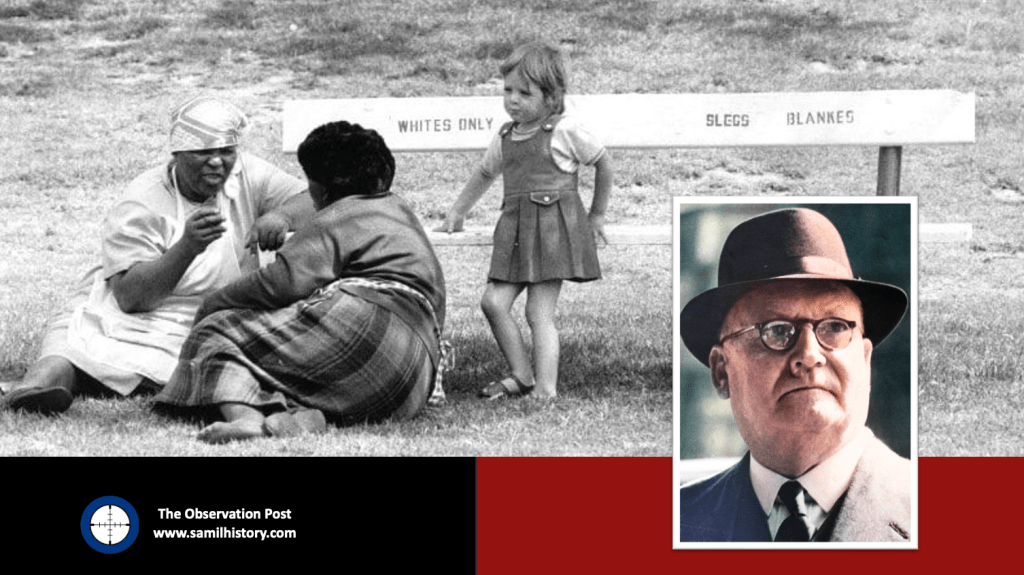

In terms of historic sweep, Pirow is a highly accredited advocate and counsellor, however, he is also the previous National Party Defence Minister under Hertzog and the founder of the National Socialist ‘New Order’ think tank within the National Party prior to the war. Oswald Mosley, on the other hand is the previous leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) which had played a significant role in influencing many of the British nationals to join the Waffen SS and the BFC. After the war (and his imprisonment) Mosley releases his book “The Alternative” in October 1947, which is a re-hashed National Socialist ‘New Order’.110 Prior to the war, Oswald Pirow and Oswald Mosely, even as early as 1938, have been in contact collaborating with one another. Just after defending the BFC South African renegades treason cases in April 1947, Pirow makes contact with Mosley again and they collaborate on a paper for a fascist and racially separated African order.111 They come up with the Mosley-Pirow Proposals, which were:

‘a natural development of General Hertzog’s Segregation Policy and was foreshadowed by (his) then cabinet colleagues 15 years earlier’.112

The proposals essentially divide Africa into a large southern ‘white’ state with its labour provided by separate ‘black’ vassal states on temporary work permits. The work foreshadows the Apartheid Bantustan program and influx control policies.113

This mutual political disposition and outlook between ‘the two Oswald’s’ is an interesting twist as it signals what sort of post war sentiment there is in many parts of South Africa, even years after the war is over. Mosley is regarded as ‘the most hated man in Great Britain’ and his writings that of the ‘loony’ right. Pirow on the other hand is taken a little more seriously in South Africa, he’s eventually appointed the State Prosecutor in the Treason Trial and these writings of his foreshadow some the National Party’s policies on Apartheid.

Pirow’s involvement as defence council in all the cases of South African renegades is interesting – be they people caught spying for Nazi Germany in South Africa, or be they members of Radio Zeesen broadcasting Nazi propaganda to South Africa or be it this case, the South Africans joining the Waffen SS. In all instances Pirow – as a previously committed and vocal Nazi and anti-Communist politician – is “protecting his own” and bringing his formidable legal and political skills to bear in doing this. His presence alone would give an atmosphere that Nazism and Fascism were normative and accepted practices in some communities in South Africa before and during the war, so too the deep seated hatred and fear of Communism. His open relationship with Mosely, and support of British fascism also gives a little gravitas to the British Union of Fascists (BUF) and all the BFC members who belonged to it.

Waffen SS Propaganda – Dutch and South African

An interesting facet of the Waffen SS and BFC story is the extreme hatred for Communism and the fear of the on-set of Bolshevism in Europe, the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. So how successful was Nazi Germany in recruiting Waffen SS members from foreign counties on the same premise of anti-bolshevism? On a cultural, language and historical basis (as its shared) the closest we can compare the recruitment of South Africans into the Waffen SS, especially Afrikaners, is to compare the appeal the German’s made to recruit the Dutch and its successes.

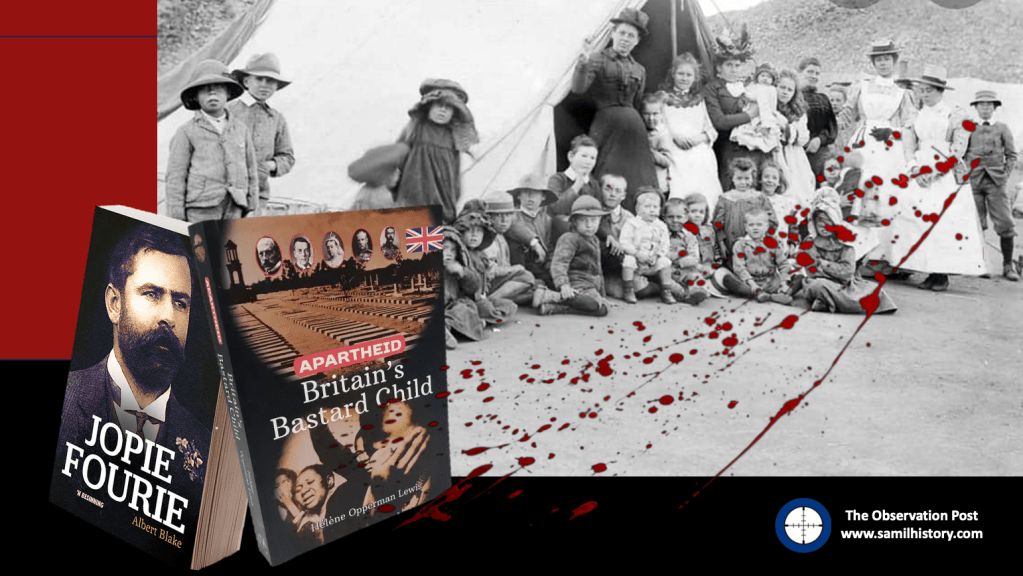

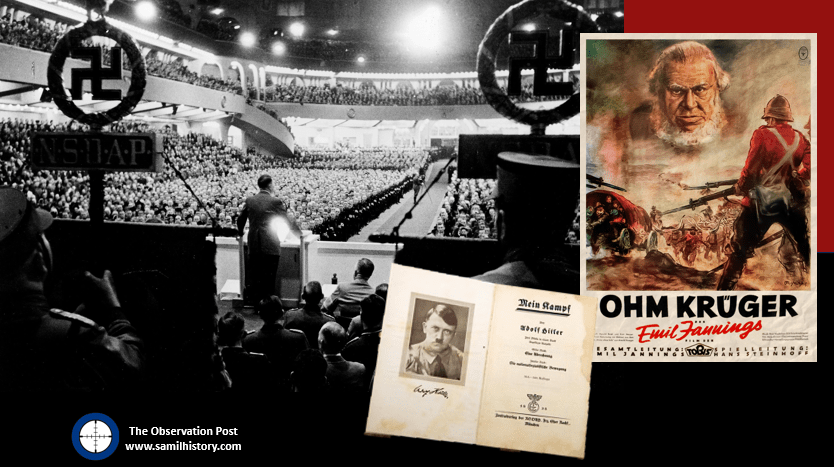

The appeal for Dutch recruits into the Waffen SS has a distinctive South African message. Hitler in 1940, is a firm fan of the Afrikaner Nationalist cause and shares the ‘politics of pain’ caused during the South African War with them. Hitler’s passion for Boer politics starts early and he states in his autobiography Mein Kampf:

‘The Boer War came, like a glow of lightning on the far horizon. Day after day I used to gaze intently at the newspapers … overjoyed to think that I could witness that heroic struggle.”114

On 30th January 1940 at the Sportspalast, during his speech, Hitler drives his pro-Afrikaner Nationalism positioning home when he makes two significant points, he says:

“They (Britain) waged war for gold mines and mastery over diamond mines.”115

Then later in the speech Hitler says:

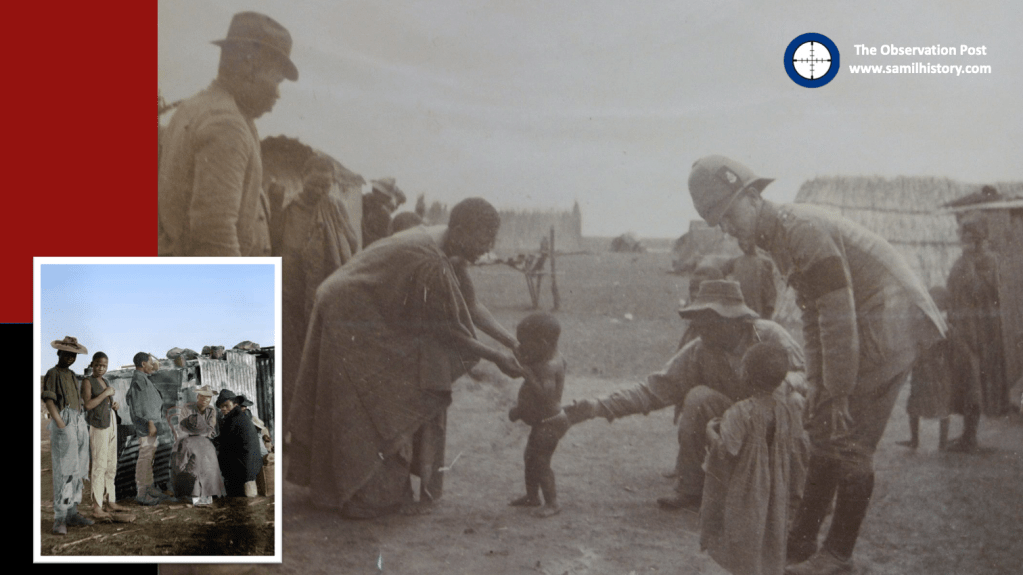

‘When has England ever stopped at women and children? After all, this entire blockade warfare is nothing other than a war against women and children just as once was the case in the Boer War, a war on women and children. It was there (South Africa) that the concentration camps were invented, in an English brain this idea was born. We only had to look up the term in the dictionary and later copy it .. with only one difference, England locked up women and children in their camps. Over 20,000 Boer women (and children) died wretchedly at the time. So why would England fight differently today?’

Later Hitler would again engage his propaganda ministry to drive his opinion on the Boer War, Joseph Goebbels who on 19 April 1940, on Hitler’s birthday speech, would broadcast over Radio Zeesen (and others), and he said:

‘Get rid of the Führer or so-called Hitlerism … British plutocracy had tried to persuade the Boers during the South African war of the same thing. Britain was only fighting Krugerism. As is well known, that did not stop them from allowing countless thousands of women and children to starve in English concentration camps.’116

Ohm Krüger (Uncle Paul), a movie about the Boer War is released in 1941 – it’s Joseph Goebbels’ masterpiece on South Africa. Winner of the Reich Propaganda Ministry’s “Film of the Nation” rating (one of only 4). The movie is a propaganda masterstroke which would reach millions all across Europe, especially in the Netherlands and related territories. Directed by Hans Steinhoff the story is about Paul Kruger, the Transvaal Republic President, and the Boer War from a ‘Dutch’ (Boer) perspective and it climaxes with the massacre and starvation of Boer women and children in British concentration camps – it’s highly inaccurate and an historic fabrication, however it nevertheless strikes a chord with the Dutch, who supported the Boer cause during The South African War.

Dr Erik Holm – the South African Afrikaans broadcaster for Radio Zeesen would recall Hitler’s open admiration for General Christiaan De Wet during the Boer War and his guerrilla tactics in flummoxing the British – from conversations he personally had with the Führer on the Boer War.117

The Nazi propaganda ministry and the Waffen SS used this very powerful affinity and memory to the South African War to appeal to the Dutch, playing on the sense of injustice done to their “Dutch” cousins in Africa by the British, bearing in mind the South African War still in living memory for many elderly Dutch and still a point of deep political outrage. At the same time the Germans cleverly conflate the call to action to fight against onset Bolshevism (Communism) with the political outrage of the South African War to drive Dutch volunteerism – especially to the ranks of the Waffen SS.

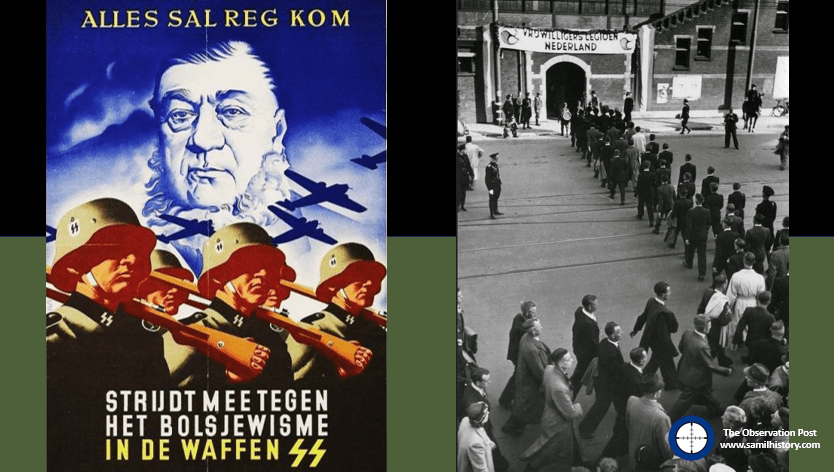

One wartime Waffen SS recruitment poster demonstrates this sentiment perfectly, it shows an image of the Transvaal Republic Boer Republic President – Paul Kruger in a mythical sense of memory, it has a famous period quote by the Orange Free State Boer Republic President Johannes Brand ‘Alles sal recht komen als elkeen zijn plicht doet’ or simply ‘Alles sal reg kom’ (all will be well) – and the main call to action in Dutch reads ‘Fights against Bolshevism in the Waffen SS.’

In targeting this Dutch and Flemish community which is historically and culturally very closely associated and linked to the Afrikaans community, we see some of Nazi Germany’s greatest success in recruiting for the Waffen SS. According to the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation is estimated that between 20,000 to 25,000 Dutch volunteer to join the Waffen SS 118 (almost twice the number that join the Dutch Resistance). These Dutch Waffen SS all go on to demonstrate a high degree of fighting prowess, military discipline, strong battle order and an almost fanatical focus in their defence of Europe against the counter-attacking Soviet Red Army and its Allies.

The vast difference between the Dutch versus the South African recruits to the Waffen SS, on the same call to action and historical affinity, is seen statistically – in the numbers alone – 25,000 Dutchmen and only 3 South Africans, and this alone draws its own conclusion. The recruitment campaign for the BFC is statistically insignificant in comparison with just about every key ethnic formation in the Waffen SS, the BFC are numerically inconsequential.

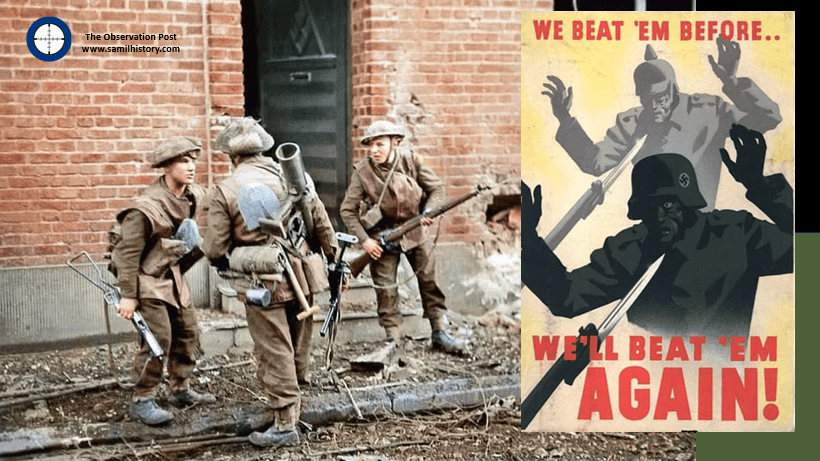

A key difference to note here is that the threat of Bolshevism is seen in an entirely different way in Europe as opposed to the United Kingdom and its Commonwealth when it comes to propaganda and political rhetoric. In the United Kingdom and South Africa, both Winston Churchill and Jan Smuts position the Soviets as key allies first, as Smuts notes in his speech to both houses of the British Parliament in 1942, he refers to Russia’s ‘indomitable spirit’, having taken the hardest blows and made the ‘most appalling bloodletting necessary for Hitler’s defeat’ and because of this ‘they alone‘ can win the war.119 In general the Allied propaganda and messaging points to a prioritisation to defeating “Hitlerism” first as the greater of the two evils, a more imminent priority is to stand “Together” with the Soviet Union and defeat the common enemy. Examples of this propaganda and messaging are seen in the posters below:

This propaganda is in sharp contrast to the German messaging when it comes to Europe defeating Communism and the prioritisation of this endeavour as the greater evil. This is especially apparent in Waffen SS posters and propaganda targeted at citizens of ‘Germanic regions and peoples’ – the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway where National Socialism prior to World War 2 is far more palatable as a social order for Western Europe than Communism.

Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner the III SS Panzer Corps Commander would note that the highly unstable socio-economic conditions in Europe in the 1930’s caused by the Great Depression impacted the youth of Europe and led to ‘intellectual despair’ which in turn contributed to Waffen SS recruitment. To Steiner, the European youth were so disillusioned by the apparent helplessness and instability of their own governments many began to search for an ideal that would give meaning to their lives and tended to regard developments in the Third Reich with ‘idealistic hopefulness.‘120 For these recruits, Communism and future uncertainty it offered is superseded by their adoration for the discipline and successes of Nazism and as a net result the Waffen SS recruitment for its “Nederland”, “Norland”, “Wiking” divisions and other Legions such as the “Flemish Legion” and “Walloon Legion” is highly successful.

This exceedingly low conversion rate of British, Canadian, New Zealand, Australian and South African POW to the Waffen SS is held up by the fact that in these servicemen by and large followed the prevailing call to action in their countries to fight as a collective to beat Hitlerism as a priority. These POW simply do not have the same frame of reference as the European youth, and it can be proposed that their loyalty to their country’s Casus Belli supersedes all else, especially in South Africa where all serving in Africa and Europe were volunteers.

Even militarily speaking, where the Norland and Wiking divisions of the Waffen SS, as well as other ethnic divisions and legions are renowned for almost fanatical battlefield prowess and highly disciplined battle order, the BFC is ineffectual as a fighting unit. Although the BFC is only a platoon size and although they spend a month in the combat theatre in earthen trenches with a sense of determination, they were fractured, ill-disciplined, inclined to desertion and highly compromised, as pointed out by Colonel S.T. Pretorius, a prosecutor during the trial of the South African Waffen SS members, had the Red Army attacked their position they would have run over them with ease. According to Pretorius:

… the BFC was a ‘dismal failure’, ‘never up to strength’, ‘the members could never agree amongst themselves’ and at times ‘the Germans did not know what to do with these men.’121

The fractured nature of the BFC and that it is no match for the Waffen SS Norland division it has been attached to also supports the notion that BFC simply did not share the moral convictions or values of their Waffen SS counter-parts and were simply not fit for purpose.

In Conclusion

In the United Kingdom, the British renegades joining the Waffen SS or involved in propaganda in support of British POW joining the Waffen SS received a broad range of sentencing, however in general those found to be in leadership positions – fully committed to fighting Bolshevism on behalf of Nazi Germany and serving in German uniform with ‘hostile intent’, as well as those at the heart of the propaganda initiatives received severe High Treason guilty sentences, some received the death sentence and others harsh sentences of lengthy imprisonment with hard labour. This has a lot to do with retribution and intolerance of Nazism in the post war environment in the United Kingdom.

The British ‘rank and file’ in the British Free Corps receive varying degrees of sentences, some prison time, time already served to acquittal, this has a lot to do with war weariness and the wish for new horizons, which are the grounding reasons underpinning the change in government in 1945 and would see Winston Churchill lose his premiership and his Conservative Party out of power, of which given his success in World War 2 Churchill was certain would be retained. The Labour Party’s emphasis on social reform clearly resonated with a war weary Britain and gave Labour a landslide victory at the polls and a clear mandate for change.122

In South Africa the matter is treated somewhat differently, the advent of the National Party to power in 1948 would see all South Africans involved in collaborating with Nazi Germany receive full amnesty, however even prior to that the High Treason cases are handled somewhat leniently in comparison to those in Britain, and this also has a lot to do with war weariness, a reconciliatory post war environment and Smuts’ continued appeasement of an irreconcilable Afrikaner Nationalist community in South Africa tolerant of Nazism and Nazi Germany.

The socio-political landscape in South Africa, prior to, during and after the war is substantially different to that of the United Kingdom – or any of the other Commonwealth countries. South Africa is the only country in the Allied mix where a significant majority did not fundamentally support going to war – although South Africa’s black population saw an opportunity to improve political emancipation, the support in joining the war effort was not broad in relation to population. In the white population, suitably enfranchised, a very significant swathe of whites were in antitheses to the call to war with Nazi Germany and in fact many in direct support of Nazi Germany.123

As with Churchill in the United Kingdom, Smuts in South Africa was buoyed by his strong electoral performance in 1943, mid way into the war, where he held a clear constitutional majority. Smuts, like Churchill, did not see his opposition, the Afrikaner Nationalists also take up the mantra of social reform at the end of the war, demanding change with a new reform policy called Apartheid, and it also held a high appeal to a war weary nation still bitterly divided over Smuts’ decision to go to war. In a surprise 1948 General Election result the Reunited National Party and its partners were able to sneak in on a single constitutional seat and oust Smuts. The new Minister of Justice C.R. Swart on 11 June 1948 issued a statement of general amnesty for individuals convicted of war crimes relating to treason, the statement read:

‘(The National Party) government (wanted) to relieve the people of the Union from the strain of the war years and to endeavour to end all the unpleasantness and rancour that flowed from it’124

By October, the majority of South African men who had sympathised with, or supported Nazi Germany directly were released, the South Africans who had served in the Waffen SS found themselves free of prosecution, their decision to support the Nazi state and fight Communism a favorable one in the eyes of the incoming nationalist government. A different matter entirely in Germany, from 20 November 1945 to 1 October 1946, the Nuremberg Trial takes place and exposes the full criminality of the Nazi Party regime and its ideology. The National Socialist dogma with its focus on the bogus “protocols of the elders of Zion”, which blamed all of Germany’s economic, social and political problems on Judaism, Freemasonry and Communism and was used to justify the holocaust and the massacre of soviet citizens and POW en masse along racial and political lines is exposed as willful genocide and deemed a crime against humanity.

Although Nazi ideology and dogma was no longer tolerant in the political sphere in South Africa after 1945, ‘no solid measures were put in place by the Smuts government to prevent it from flourishing. Afrikaner Nationalists entertaining strong National Socialist ideologies and having committed treason and sedition during the war, who in European countries would have been hanged for war crimes, landed up back in mainstream party politics under the banner of the National Party and many even ended their days in Parliament.’125

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

Footnotes

- D Harrison, The White Tribe of Africa: South Africa in Perspective (Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981), 99. ↩︎

- Harrison, The White Tribe of Africa, 99. ↩︎

- TRP Davenport, South Africa, A Modern History. Cambridge Commonwealth Series (London: Macmillan Publishers 1977). ↩︎

- B Bunting, 1964. The Rise of the South African Reich (London: Penguin Books 1964), 41. ↩︎

- Harrison, The White Tribe of Africa, 112. ↩︎

- ‘Elections in South Africa’, African Elections Database, 10 November 2004. Accessed 8 August 2024 ↩︎

- DB Katz, ‘General Jan Smuts and his First World War in Africa 1914–1917’ (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers 2022), 34-35. ↩︎

- Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich, 57. ↩︎

- FA Mouton, ‘Beyond the Pale’ Oswald Pirow, Sir Oswald Mosley, the ‘enemies of the Soviet Union’ and Apartheid 1948 – 1959, Journal for Contemporary History, 43, 2 (2018), 18. ↩︎

- Mouton, ‘Beyond the Pale’, 20. ↩︎

- FL Monama, Wartime Propaganda in the Union of South Africa, 1939 – 1945 (Dissertation for the degree of history, University of Stellenbosch. Stellenbosch, 2014), 62. ↩︎

- M Shain, ‘A Perfect Storm’, Antisemitism in South Africa 1930-1948, (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2015) , 55–58. ↩︎

- W Bouwer, National Socialism and Nazism in South Africa: The case of L.T. Weichardt and his Greyshirt movements, 1933-1946. (MA Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein 2021), 18. ↩︎

- Shain , A Perfect Storm, 41. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 84. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 76. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 82. ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 230. ↩︎

- Bunting, The Rise of the South African Reich, 84 ↩︎

- Shain, A Perfect Storm, 231. ↩︎