To fully reconcile The Boer War is to fully understand the Black Concentration Camps.

Two Different Narratives

To many Afrikaans speaking white people in South Africa the narrative of what many in South Africa call; The Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) or just shortened to The Boer War, is one of a struggle of the Boer nations for independence, the backdrop set against one of British greed for gold in The South African Republic (Transvaal) and colonial expansion by the subjugation of independent nations. The Boer’s boldly fighting against the odds against a British Imperialist invasion and then having to endure the indignity of a systematic eradication of the Boer nation and culture by means of a punitive genocide initiated by what some now regard as a Nazi styled system of British ‘concentration camps’ which murdered their women and children in their tens of thousands. An indignity and outrage which now calls for an apology and war repatriation from the British.

To many of the British, the story is somewhat different. The British call the war; The South African War (1899-1902) and it is one of a struggle of British migrant miners fighting against oppression and for citizen rights in The South African Republic (The ZAR or Transvaal). Followed by brave pockets of British garrison troops in border towns in the Cape Colony and Natal fighting off an invasion by the Boers of their colonies, the siege of their towns initiated by the Boer’s declaration of war on the British, and by besieging their towns subjecting British civilian men, women and children to starvation and indiscriminate shelling by surrounding Boer guns – calling for a national outrage in the UK and a ‘call to arms’ of the biggest expeditionary force seen to date to ‘get their cities back’ and save the civilians. Then after winning the conventional in a lightning war of only 9 months the British felt forced to depopulate large swathes of land bordering their supply routes to Pretoria. This was done to prevent constant attack on their supplies by Boer commandos (now with governments ‘in the field’ instead of their capital cities). Their reaction, wherever there was an attack, just put all the surrounding farmstead folk into ‘refugee camps’ (their term for the camps) and burn the farmsteads supplying the Boer forces to the ground. All because some renegade Boer commandos didn’t ‘play by the rules’ of a conventional surrender and embarked on an unconventional phase of the war instead (guerrilla war) which threw the generally accepted rules of engagement out the window.

Nasty, very nasty history this war was, and these two different views on the subject are to a degree both ‘politically’ motivated, both conveniently serving to underpin ‘Nationalist’ ideologies and in so supporting political agendas – whether it is a Boer or British one.

A third dimension

So, somewhere between the two vastly different narratives lies the truth, but there’s a third part of the war neither of the above two narratives even begins to properly consider, and it’s a part of the Boer/South African War which fundamentally shifts all previous narratives on the war, moving it away from a war between two white tribes to a more holistic one involving all South Africans. Ground breaking research is now been done on the ‘Black’ involvement in the war and the impact to the Black community. New understanding is coming about and it is shaking the traditional British and Boer narratives and historical accounts to the core.

At the very centre of understanding this previously overlooked aspect of the war is the unveiling of the history of the ‘Black’ concentration camps of the Boer War. Their impact to the Black community, almost no different to the impact to the Boer community. The only difference is the politically driven race politics post the Boer War, and especially during the Apartheid period, which simply brushed it aside as something less relevant with a brutal degree of apathy, leaving us all now with a ‘perception’ of the war rather than a truth.

In an odd sense, it is only by understanding this aspect of the war that full account and truths are established, that anything by way of ‘apologies’ or ‘reparations’ in our modern context can even be possible.

The Black History of the Boer War

So, if you are unfamiliar with the ‘Black’ part of the Boer War here it is. South Africa’s ‘Black’ tribal population also took part in the war, on a scale most people are unaware of.

In the case of the Boer forces, very often Black farm workers took on the role of ‘agterryers’ (rear rider) in fighting Commandos, their job was a combination of military ‘supply’ and one of a military ‘aide-de-camp’ (assistant) to one or more of the Boer fighters. These ‘agterryers’ ferried ammunition, weapons, supplies and food to the Boer combatants, they arranged feed for horses and in some cases, they were even armed.

It was not only Black men in support, but Black women too, they supported the Boer women in providing food and feed to frontline commandos and when the concentration camp systems started they (with their children) were also swept up and in many cases also accompanied and lived in the tents with the Boer families interned in the ‘white’ concentration camps themselves, primarily looking after the children (black and white), sourcing food and water as well as cooking and washing. They too were exposed to the same ravages of war in the camps as the white folk, mainly the water-borne diseases which so decimated the women and children in these camps.

The British were no different, they quickly employed the local Black population as ‘scouts’ and numerous examples exist of these ‘scouts’ conducting surveillance of Boer positions and intelligence on Boer movements as well as guiding the British through the unforgiving South African terrain.

The British also sought manpower from the local Black population in cargo loading and supply haulage. These people were as much a part of moving British military columns as any military person involved in logistics and supply and to a degree they were also exposed to hazards of war.

The British would also ‘commandeer’ entire Black tribal villages for the use of setting up forward bases, strong points and defences – putting entire village populations at risk and literally bringing them into their ‘war effort’.

There is even a recorded event when Black South Africans took a more direct role in the war. On 16 May 1902, Chief Sikobobo waBaqulusi, and a Zulu impi marched on Vryheid and attacked a Boer commando at dawn with losses on both sides.

Context behind the Concentration Camp policy

However, the biggest and most deadly impact to the Black African nations in the Boer War, came in their own earmarked British concentration camps. So how did that come about? To understand why the concentration camps initially came about and their purpose we need to put both the white and black concentration camps into context.

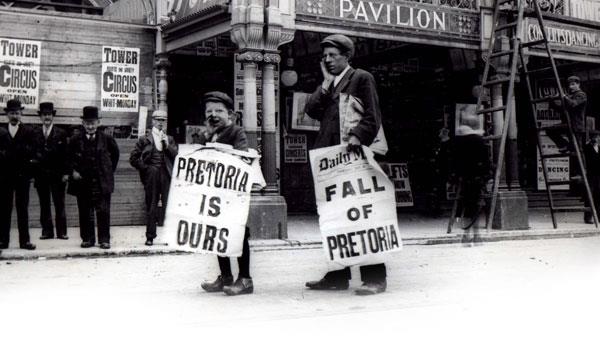

To the British, the war should have ended when they marched into Pretoria in June 1900, having now relieved the Boer sieges of their towns of Ladysmith in their Natal Colony, Mafeking and Kimberley in their Cape Colony, and having already taken The Orange Free State’s capital, and Johannesburg – the Transvaal’s economic hub. The war was over, ‘officially’ they had annexed both republics and they even called for a post war ‘khaki election’ back in the UK to reshuffle Westminster to post war governance.

Not for the Boer forces it wasn’t over – not by a long shot. The British in marching into Pretoria found themselves stretched deep into ‘hostile’ territory with extended and vulnerable supply lines stretching over hundreds of kilometres. Boer strategy was to move their government ‘into the field’, abandon the edicts of Conventional Warfare and embark on ‘Guerrilla Warfare’ tactics instead, to disrupt supply and isolate the British into pockets. To do this they would need food, ammunition and feed supplied directly from their own farmsteads surrounding their chosen targets. Isolated British garrisons came under attack with some initial Boer successes, their forces then melting away into the country. Easy targets were also trains and train lines, and after many a locomotive steamed into Pretoria riddled with bullet holes or didn’t make it all, Lord Kitchener got fed up at the arrogance of it all and acted decisively.

Kitchener concentrated on restricting the freedom of movement of the Boer commandos and depriving them of local support. The railway lines and supply routes were critical, so he established 8000 fortified blockhouses along them and subdivided the land surrounding each of them into a protective radius. Short of troops to man all these strong points (he needed 50 000 troops) and control the protective areas, Kitchener also turned to the local Black African population and used over 16 000 of them as armed guards and to patrol the adjacent areas.

Wherever and whenever an attack took place, or where sufficient threat existed to this system, Kitchener took to the policy of depopulating the radius area, burning down the farmsteads, killing the livestock and moving all the people – both Black and White (it mattered not to the British what colour they were) into what was termed a ‘refugee camp’ by the British, these camps however were in reality a concentration camp of civilian deportees forcibly removed from their homes.

Two systems of concentration camps existed, one for Blacks and one for Whites. Both were run very differently. Victorian sentiment at the time was very racially guided.

The Boer Concentration Camps

The ‘White’ camps were tented and the ‘refugees’ (more accurately forced removed and displaced civilians) were given rations of food and water. The British could also not afford the resources to ‘guard’ and administrate these camps, and herein lies the problem. It was due to the lack of ability to manage the camps that some camps were managed well and others simply were not, some fell under British military command others were ‘outsourced’ to local contractors manage, and both British and quite often Afrikaner entrepreneurs were brought in to administrate the camps. In most instances these camps were very isolated, and by isolation it simply meant the people in them had nowhere else to go (there were no Nazi styled ‘wire’ fences with prisoners shot trying to escape), the camps were in fact relatively porous with regard the movement of people in and out of them.

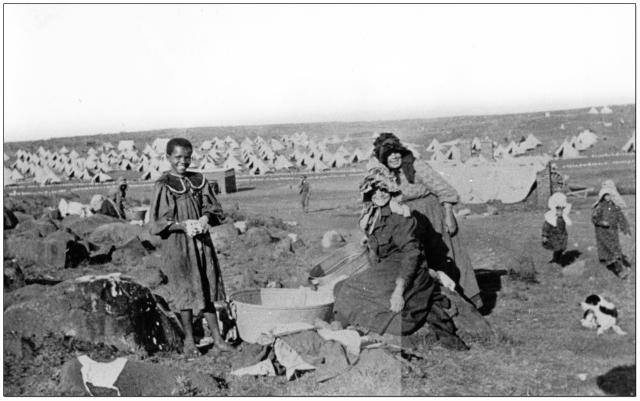

Image: Children fetching water, Bloemfontein concentration camp. Note general conditions and bell tents. Colourised by Tinus Le Roux

Some camps were well run, orderly with demarcated tent lines and health policies implemented based on running a normal military camp (tents and bedding were regularly aired out) and ablutions correctly located with drainage. Other camps were not well run at all, the administrators allowing the Boer families to ‘clump’ their tents together with no proper ablution planning or health policy. Policies on food rationing also differed from camp to camp. In some camps, sadistic camp administrators took to punitive measures to ‘punish’ the Boer families whose menfolk were still fighting in the field to get them to surrender, literally starving these people to the point that just enough food was given to keep them alive.

It follows that in these camps, especially the poorly administrated ones, that disease would take root, and it came in all sorts forms ranging from poor nutrition to exposure, but it mainly came in the form of waterborne diseases from poor sanitation. Here again, some camps were medically geared to deal with it, others not. The net result of all of this is a tragedy on an epic level.

The official figure of the death toll to white Boer women and children in the camps is 26 370, a staggering figure when you consider that only an estimated 6,000 Boer combatants in the field died in the war. Another tragedy (lesser so than life) was the loss of family heirlooms and family records to the relocation and scorched earth policies, this served to erase the inherent culture and history of the Boer peoples. The combination of both the systematic erosion of Boer culture and the astronomical rise in death rates of the ‘fountain’ of Boer race – their women and children, has left a deep scar of hatred and loss which still openly exists to this day, and for good reason.

The Black Concentration Camps

The ‘Black’ concentration camps were a different matter entirely. On the 21st December 1900, Lord Kitchener made no bones about his new concentration camp policy at the inaugural meeting of the Burgher Peace Committee held in Pretoria, where he remarked that in addition to the Boer families, both ‘stock’ and ‘Blacks’ would also be brought in.

As said, Victorian sentiment was very racially guided, and where the ‘white’ concentration camps were at least given some semblance of tents for shelter, food, aid workers, water rationing and some medical aid albeit entirely inadequate, the ‘Black’ concentration camps had very little of that.

Black concentration camps, were also earmarked to isolated areas bordering railway lines so they could be supplied – with both deportees and supplies. The isolation also became the means of containment. However no ‘tented’ constructs were provided in most instances and these Black civilians were simply left on arid land to build whatever shelters they could scourge for. They were also not given food rations on a system resembling anything near the system provided ‘white’ camps, in the white camps the food rations were basically free of charge, in the black camps they had to pay for it.

In all an estimated 130 000 black civilians (mainly farm labourers on Boer farms) were displaced and put into this type of concentration camp, 66 camps in total (with more still been identified, some sources say as many as 80 camps), all based primarily on the British fear that these Black people would assist the Boers during the war.

During early 1901, the black concentration camps were initially set up to accommodate white refugees. However, by June 1901, the British government established a Native Refugee Department in the Transvaal under the command of Major G.F. de Lotbinier, a Canadian officer serving with the Royal Engineers. He took over the black deportees in the Orange Free State in August that year and a separate department for blacks was created.

Entire townships and even mission stations were transferred into concentration camps. The Black camps differed from the Boers in that they contained large a number of males. This meant the camps were located by railway lines where the men could provide a ready supply of local labour. Work was however paid, and it was via this economy that the Black deportees could properly sustain themselves in the camps. In this respect to better understand what these camps were, the concept of a ‘forced labour camp’ would be a better definition.

Of the Black concentration camps, 24 were in the old Orange Free State Republic, 4 in the Cape Colony and 36 in the old South African (Transvaal) Republic. There was a single concentration camp in Natal at Witzieshoek, and more camps are identified to this very day . Some of the camps were for permanent habitation and others were of a temporary nature intended for transit. Their stories speak volumes for the way they were treated.

On the 22 of January 1902, At the Boschhoek Black concentration camp the deportees held a protest meeting. Stating that when they have been brought into the camps they have been promised that they will be paid for all their stock taken by the British, for all grain destroyed and that they will be fed and looked after, none of which had not been forthcoming. They were also unhappy because “… they receive no rations while the Boers who are the cause of the war are fed in the refugee camps free of charge … they who are the ‘Children of the Government’ are made to pay’.

23 January 1902 records that two Black deportees of the Heuningspruit concentration camp for Blacks, Daniel Marome and G.J. Oliphant, complained to Goold-Adams: “We have to work hard all day long but the only food we can get is mealies and mealie meal, and this is not supplied to us free, but we have to purchase same with our own money. “We humbly request Your Honour to do something for us otherwise we will all perish of hunger for we have no money to keep on buying food.”

The ‘official’ rations were meagre at best and had to be purchased, for ‘Natives’ over 12 years of age: Daily: 1½ lbs either mealies, K/corn, unsifted meal or mealie meal; ¼ oz salt; Weekly: 1 lb fresh or tinned meat; ½ coffee; 2 oz sugar – all but the corn was to cost the Black deportee receiving it 4½d per ration.

By 1902 18 January, Major De Lorbiniere, writes that supplying workers to the army ‘formed the basis on which our system was founded’. The department’s mobilisation of Black labour was very successful – however really this is not surprising at all considering the incentives offered. Those in service of the British and their families could buy mealies at a halfpence per lb, or 7/6 a bag, while those who do not accept employment had to pay double, or 1d per lb and 18/- or more per bag.

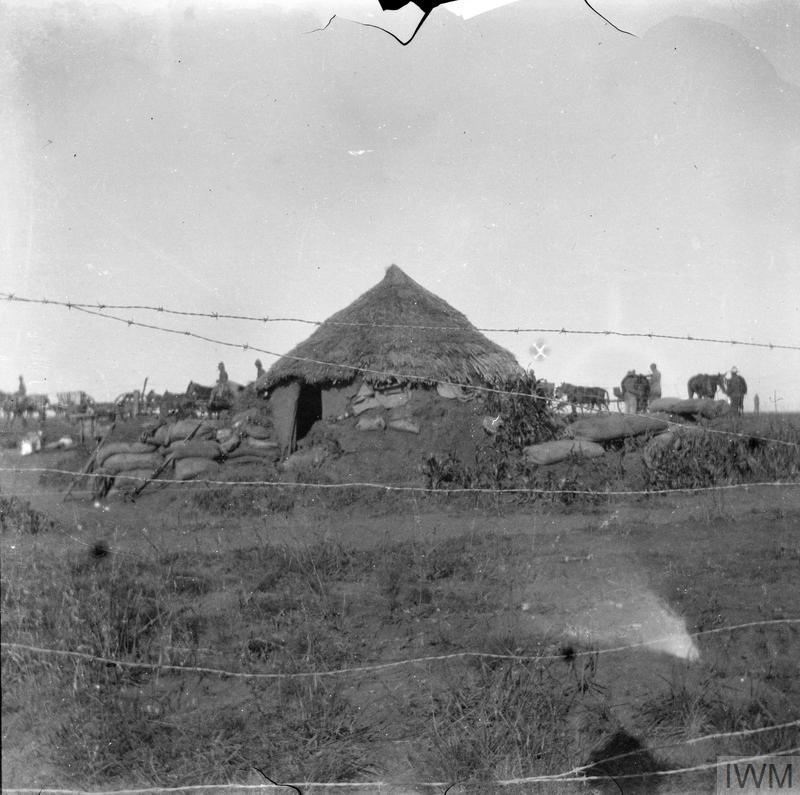

The camps, usually situated in an open veld, they were overcrowded, the tents and huts were placed too close together and did not provide adequate protection from the harsh African weather. They were extremely hot in summer and ice cold in winter. Materials for roofing were scarce, also no coal was provided for warmth. In addition to this misery there was a severe shortage of both food and water (mainly fresh vegetables, milk and meat) .

Water supplies were often contaminated by disease and any form of medical attention was rare to non-existent. Abhorrent sub-human conditions meant that water-borne diseases like dysentery, typhoid and diarrhoea spread with ease and the death rate climbed drastically.

Image: Probably Bronkhorstspruit Concentration Camp. Photo source: LSE library, colourised by Jenny Bosch. Note the lack of bell-tents and use of corrugated iron sheets for shelter.

The horrific conditions these deportees subjected to were superseded only by even more abhorrent treatment, the same social diseases, exposure and nutrition problems sprung up in these camps as they did in the ‘White’ Boer camps, with the same horrific result.

Most of the deaths in the concentration camps were caused by disease, and it took root with the most vulnerable, mainly children. By this stage in the war, the death rates in the Black concentration were climbing to unacceptable levels. An aid worker, Mr H.R. Fox, the Secretary of the Aborigines Protection Society, was made aware by Emily Hobhouse that the Ladies Commission (the Fawcett Commission – looking into the problems and death rates in the concentration camps) had focussed solely on the ‘White” concentration camps and completely ignored the plight of Blacks in their concentration camps. So, he promptly wrote to Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, requesting an inquiry be instituted by the British government “as should secure for the natives who are detained no less care and humanity than are now prescribed for the Boer refugees”.

On this request Sir Montagu Ommaney, the permanent under-secretary at the Colonial Office, responded that it seems undesirable “to trouble Lord Milner … merely to satisfy this busybody”. With that swift apathy to the plight of the Black deportees came another tragedy on an epic level.

By the beginning of 1902, conditions in black camps were however improved somewhat in order to reduce the death rate. More nutrients were introduced (tinned milk, Bovril and corn flour) and shops were opened that allowed black people to buy some produce and equipment, mainly items like flour, sugar, coffee, tea, syrup, candles, tobacco, clothes and blankets.

The total Black deaths in camps are officially calculated at a minimum of 14 154 (about 1 in 10). However recent work by Dr. Garth Benneyworth estimates it as at least 20 000, this after examining actual graveyards and factoring that burials had also taken place away from the camps themselves. Dr. Benneyworth notes that the British records are incomplete and in many cases non-existent and the fact that many civilians died outside of the camps in labour or transit or were buried in shared graves, this caused the final death toll to be much higher. The high rate of child death in the Victorian period aside, a staggering 81% of the fatalities in the Black concentration camps were children.

Images courtesy of Dawie Fourie

In Conclusion

Compare that to the Boer concentration camps, where the deaths are recorded are around the 26 000 mark and it becomes clear that the Black population of South Africa suffered the same as the White population during the Boer war. However, the fact is that historical research into the Black involvement in the war is sorely missing from the general narrative. Post the Boer war and during Apartheid a lot of research around the Boer concentration camps was done, even monuments and museums were erected to them. It served Nationalist political agenda at the time in establishing Afrikaner identity along a separate race line, so almost nothing by way of research was done on the Black concentration camps, no monuments, museums or even a solid historical account exist of them at all. The Black history of the Boer war most certainly did not make it into mainstream ‘National Christian’ government education curriculum at the time. As a result the Boer war is simply just not properly understood to this day.

If you add to this the glossed over South African Black History behind their contributions and sacrifices in WW1 and WW2, you can see that Race Politics in South Africa has simply not taken the Black history and their sacrifice along with the mainstream historical account, especially the history prior to the implementation of Apartheid in 1948. What this alienation of critical parts of our history from the overall historical record has done, has reinforced the narrative that black lives were somehow of a lesser consequence to white lives. So, there is no surprise that most modern South Africans (mainly youth) simply can’t be bothered with properly understanding South African history prior to 1994.

There is still a very long way to go to fully understanding the war – but the future in reconciling the true effect of this war and redressing it as a nation – is to understand that the Boer War was not only a ‘white’ man’s war, nor the concentration camps strictly about Afrikaner women and children, a much bigger story exists and its one which needs to be reconciled with – and that is the suffering of South Africa’s black population and the extraordinary losses they experienced in these concentration camps too.

The redress for white Afrikaners in South Africa as to any form of global awareness and world condemnation of this tragedy to their nation lies in the reconciliation of the history with the previously unwritten and misunderstood black history behind The Boer War. Only if his tragedy is seen as a national issue, with a common cause and reconciliatory national healing process behind it to deal properly with it, only then can amends and long awaited apologies from the British be found.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens with references and extracts from the Military History Journal Vol 11 No 3/4 – October 1999 Black involvement in the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902 by Nosipho Nkuna, also references from Dr Garth Benneyworth and ‘Erasure of black suffering in Anglo-Boer War’ By Ntando PZ Mbatha. Photo copyrights – The Imperial War Museum and Dawie Fourie.

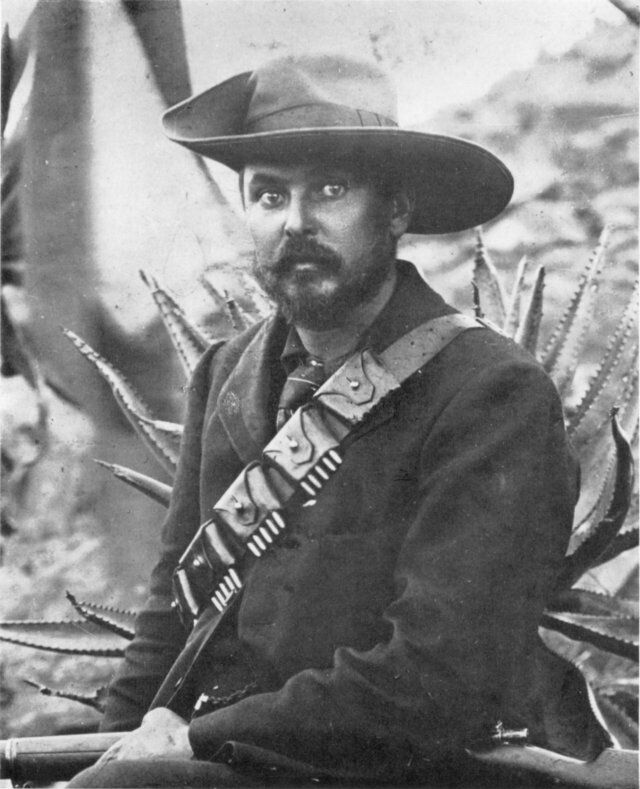

At the onset of the war in 1899, Louis Botha initially joined the Krugerdorp Commando, he fought under Lucas Meyer in Northern Natal, and later as a General commanding and leading Boer forces rather impressively at the Battle of Colenso and then at the Battle of Spion kop.

At the onset of the war in 1899, Louis Botha initially joined the Krugerdorp Commando, he fought under Lucas Meyer in Northern Natal, and later as a General commanding and leading Boer forces rather impressively at the Battle of Colenso and then at the Battle of Spion kop.

Winston Churchill took initially part in the 2nd Anglo Boer War as a ‘war correspondent’ for The Morning Post. War Correspondents like Churchill tended to be commissioned officers serving in uniform attached to Regiments or formations, their reporting was intended to toe the military line. South Africa literally made Churchill into a national hero and it is the epicentre of his rise to political greatness.

Winston Churchill took initially part in the 2nd Anglo Boer War as a ‘war correspondent’ for The Morning Post. War Correspondents like Churchill tended to be commissioned officers serving in uniform attached to Regiments or formations, their reporting was intended to toe the military line. South Africa literally made Churchill into a national hero and it is the epicentre of his rise to political greatness.

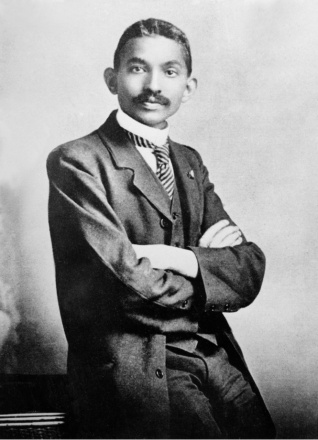

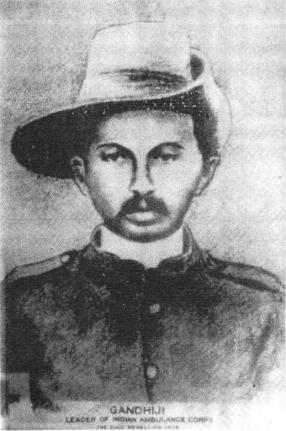

Mahatma Ghandi first saw action with Buller’s forces at the Battle of Colenso on 15 December 1899, when the Natal Volunteer Ambulance Corps we ordered to remove the wounded from the front line and then transport them to the railhead.

Mahatma Ghandi first saw action with Buller’s forces at the Battle of Colenso on 15 December 1899, when the Natal Volunteer Ambulance Corps we ordered to remove the wounded from the front line and then transport them to the railhead. It was on such occasions the Indians proved their fortitude, and the one with the greatest fortitude was the subject of this sketch [Mr. Gandhi]. After a night’s work, which had shattered men with much bigger frames I came across Gandhi in the early morning sitting by the roadside – eating a regulation Army biscuit. Everyman in Buller’s force was dull and depressed, and damnation was heartily invoked on everything. But Gandhi was stoical in his bearing, cheerful, and confident in his conversation, and had a kindly eye. He did one good… I saw the man and his small undisciplined corps on many a field during the Natal campaign. When succour was to be rendered they were there.”

It was on such occasions the Indians proved their fortitude, and the one with the greatest fortitude was the subject of this sketch [Mr. Gandhi]. After a night’s work, which had shattered men with much bigger frames I came across Gandhi in the early morning sitting by the roadside – eating a regulation Army biscuit. Everyman in Buller’s force was dull and depressed, and damnation was heartily invoked on everything. But Gandhi was stoical in his bearing, cheerful, and confident in his conversation, and had a kindly eye. He did one good… I saw the man and his small undisciplined corps on many a field during the Natal campaign. When succour was to be rendered they were there.”

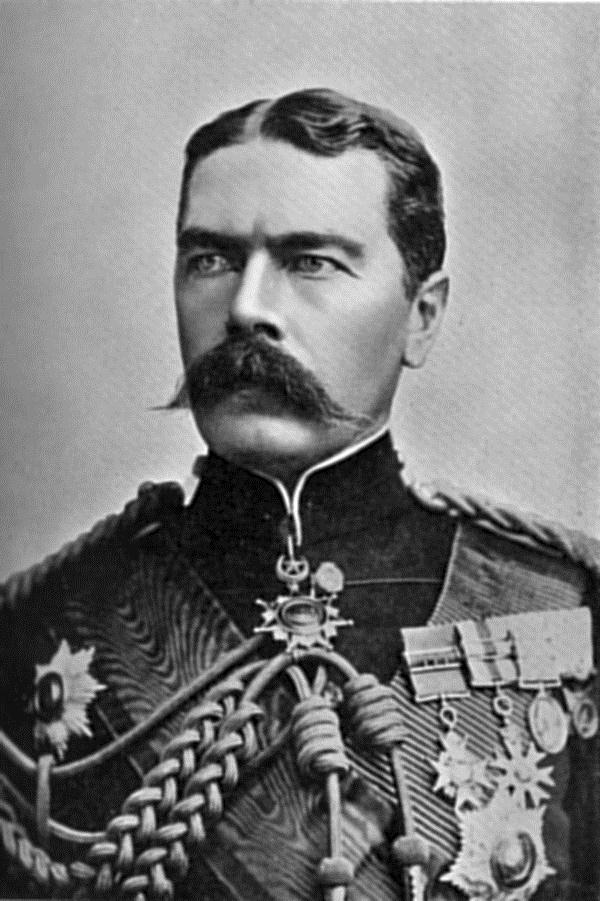

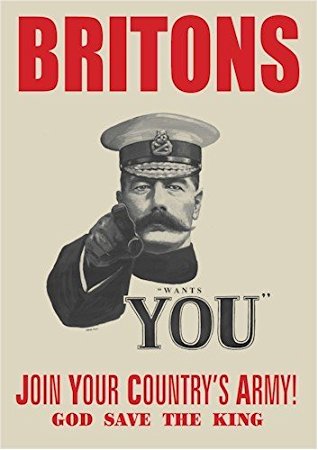

You’ll recognise Lord Kitchener anywhere – he became the poster model for the “Your Country Needs You” campaign to spur British and Commonwealth men to sign up and fight in the trenches of World War 1. The poster is funnily seeing a little contemporary resurgence in celebration of the centenary of WW1.

You’ll recognise Lord Kitchener anywhere – he became the poster model for the “Your Country Needs You” campaign to spur British and Commonwealth men to sign up and fight in the trenches of World War 1. The poster is funnily seeing a little contemporary resurgence in celebration of the centenary of WW1.