So, if you like me and love your beer, and as a brewery owner I can’t help myself – Munich (or München in German) is THE place to go. Bavaria’s capital and it’s the venue of the Octoberfest and there is much ‘Ein Prosit der Gemütlichkeit’ (cheers to the sociability), Zigge, Zagge, Hoi, Hoi, Hoi and clunking of large vessels of beer called Steinzeugkrug full of cold, hoppy, golden nectar. It’s a fun place, I certainly love it, it’s a beer lover’s Mecca – no doubt.

But as a purveyor of fine history snippets too, my love of history also kicks in, and in Munich, there is a very sinister and dark past, and there’s tonnes of, literally tonnes of inconvenient history. You would not notice it today as an average tourist “in it for the beer,” Munich has been ‘scrubbed clean’. There is almost no evidence of its history as the epicentre and cultural pilgrimage of Nazism. In fact they go a long way in Munich not to celebrate World War 2 historic tourism, but that has not stopped a couple of freelance ‘independent and opportunist’ tour guides pulling an informal crowd for the unofficial Nazi tour of beer-houses and locations attended by the likes of Hitler and his cronies.

The sterility of Munich got me thinking, at what point is the removal of statues and memorials deemed ‘offensive’ perfectly acceptable and what point is it not? At what point do we, like the city of Munich .. ‘scrub’ out our past completely, disregard the idea of preserving it for the purposes of a history teaching (even a lesson on the evilness it incurred) and hide it for fear of offending victims of it.

So what’s the big deal of this totally bland corner of the Feldherrnhalle monument (Field Marshal’s Hall – built in 1841 by King Ludwig I to celebrate the Bavarian Army), located on the Odeonsplatz – Munich’s town square. Here I am with my usual ironic grin celebrating the complete nothingness of what was a ‘holy’ site to Nazism – that exact nondescript corner – the site of huge pilgrimages and parades. The only evidence left, some plug holes in the original monument that held up the gigantic Nazi add-ons. Heck, this corner was so important that as an average Munich citizen you saluted the corner of this building – ‘Nazi style’ – whenever you walked passed it. Now there is nothing, not even an information plaque.

The importance of beer halls in establishing Nazism

Well, apart from being a historic monument to Bavaria, the Feldherrnhalle is also central to all the traditional beer halls and beer gardens located around is, and it’s in two of these nearby beer halls that this story begins. The famous Bürgerbräukeller beer hall – completely demolished now and replaced with a modern culture, music and arts centre, and the Löwenbräukeller beer hall. You can still visit the Löwenbräukeller (I have) and give a complimentary Ein Prosit and Zigge Zagga to the resident Oompa band, and again – nothing, zilch, nada on its Nazi history – not even on their website.

So, in the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall, Nazism as an ideology was effectively born and took hold. Central to the beer hall was a rectangular grand hall which could accommodate up to 3,000 people and a large cellar, ideal for political meetings and rallies. From 1920 to 1923, the Bürgerbräukeller was one of the main gathering places of the Nazi Party, it was effectively established there, and it was from there that Adolf Hitler launched the infamous Beer Hall Putsch (revolt) on the 8th November 1923. Also known as the Munich Putsch, in essence Hitler and his fellow Nazi cronies attempted to pull off a military coup and overthrow the Weimar Republic.

Images: Bürgerbräukeller’s Great Hall left as it was then, Löwenbräu keller, as it is now.

Throughout 1923, the economic and political crisis struck. The Nazi Party and other nationalists believed that an armed takeover of Bavaria was possible and could even overthrow the Republic in Berlin. Hitler and the Nazi Party collaborated with others such as General Erich Ludendorff and Gustav von Kahr (a founding right wing Nationalist leader) to put a plan together to attempt a military coup. By August 1923, the plan was set and weapons and transport were gathered. However by November 1923, some of the Nazi conspirators got cold feet as news came in that the German Army in Berlin would support the government and not the conspirators.

Hitler, realising that von Kahr sought only to control him and did not have it in him to initiate a coup, utterly frustrated by it all Hitler was determined that the plan would go ahead. On the 8 November 1923, he and a contingent of the party’s SA (Storm Detachment/Troopers) marched into the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall whilst von Kahr was giving a speech to 3,000 people there. The SA surrounded the hall and set up a machine gun. Hitler, surrounded by his associates including Hermann Goring, Rudolf Hess, Alfred Rosenberg, Adolf Lenk, Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, Wilhelm Adam, Robert Wagner and others (20 in total) then jumped up a chair, fired a gun-shot and shouted “The national revolution has broken out! The hall is surrounded by six hundred men. Nobody is allowed to leave.”

He went on to state that the Bavarian government was deposed and declared the formation of a new government with General Ludendorff as the head. At gun-point Von Kahr gave his support to Hitler. Dispatches were sent to trigger Ernst Röhm and his paramilitary group the Bund Reichskriegsflagge (Imperial War Flag Society) waiting at the Löwenbräukeller Beer Hall and Gerhard Rossbach who had a detachment right wing students at a nearby infantry officers school.

The Putsch was on. After his speeches Hitler received resounding applause from the crowd at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall and Von Kahr and other members of the Bavarian government were taken into custody, Hitler departed the hall later in the evening to deal with another crisis, and mistakenly Von Kahr and his associates were released (they later took the opportunity to denounce the Nazi Party as illegal and join the government).

The night was marked by confusion and unrest among government officials, armed forces, police units, and individuals deciding where their loyalties lay. Early in the morning on the 9th November 1923 (around 3am), the first shots fired in the Putsch occurred when a local Reichswehr Army detachment loyal to the government spotted Röhm’s men coming out of the Löwenbräukeller Beer Hall. Encountering heavy fire Röhm and his men were forced to fall back. In the meantime, the Reichswehr officers put the garrison on alert and called for reinforcements.

Later that morning on 9 November, Hitler realised the Putsch had stalled, about to give up, and not sure what to do, the Putschists were rallied again by General Ludendorff who shouted “We will March” and with that Röhm’s force together with Hitler’s force (approximately 2000 men) marched out – but with no specific destination in mind. On the spur of the moment, General Ludendorff decided to lead them to the Bavarian Defence Ministry – which would take them past the ….. Feldherrnhalle and the Odeonsplatz … and here is where the corner of the Feldherrnhalle becomes important, because as they rounded this unremarkable corner of the monument they were met with 130 government soldiers and police blocking their way – and they found themselves in what is a fairly narrow road aside the monument in a sort of ‘Mexican Stand-off.’

Image: Nazi Putsch members – 9 November 1923

The two groups exchanged fire with one another, in all 4 were killed in the government’s forces and 16 Nazi Putschists were killed. In the firefight a couple of key things happened – most importantly the equivalent of a rather crooked ‘Sacred Cross’ legend was born .. the ‘Blutfahne’ (‘blood flag’). The Flag Bearer of the Nazi Flag was a SA member, Heinrich Trambauer, and he was badly wounded dropping the flag splattered with his blood, a second SA man, Andreas Bauriedl, was shot dead and fell dead onto the fallen flag, covering it in more blood. Secondly. Hermann Göring was badly wounded – and this wound would haunt him his entire life, leading to his violent morphine drug addiction which resulted in irrational decision making during the Second World War. The game was up, the Nazis scattered or were arrested. Göring escaped and was smuggled to Innsbruck. Finally, Hitler now on the run was arrested two days later on the 11th November 1923.

Hitler was sent to Landsberg Prison and put on trial for treason. Hitler’s trial took place from the 26 February to the 1 April 1924, he was ultimately found guilty of treason, but, with a sympathetic judge, he was sentenced to just five years in prison. Of this five years, Hitler only served nine months. But most importantly for the Nazi movement and to the detriment of the rest of world, Hitler was imprisoned alongside Rudolf Hess, Hess was a Hitler groupie – and held a fanatical admiration of him. He was also very articulate and ‘balanced’ Hitler enough to assist in writing Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler (My Struggle) which honed Nazi ideology and philosophy.

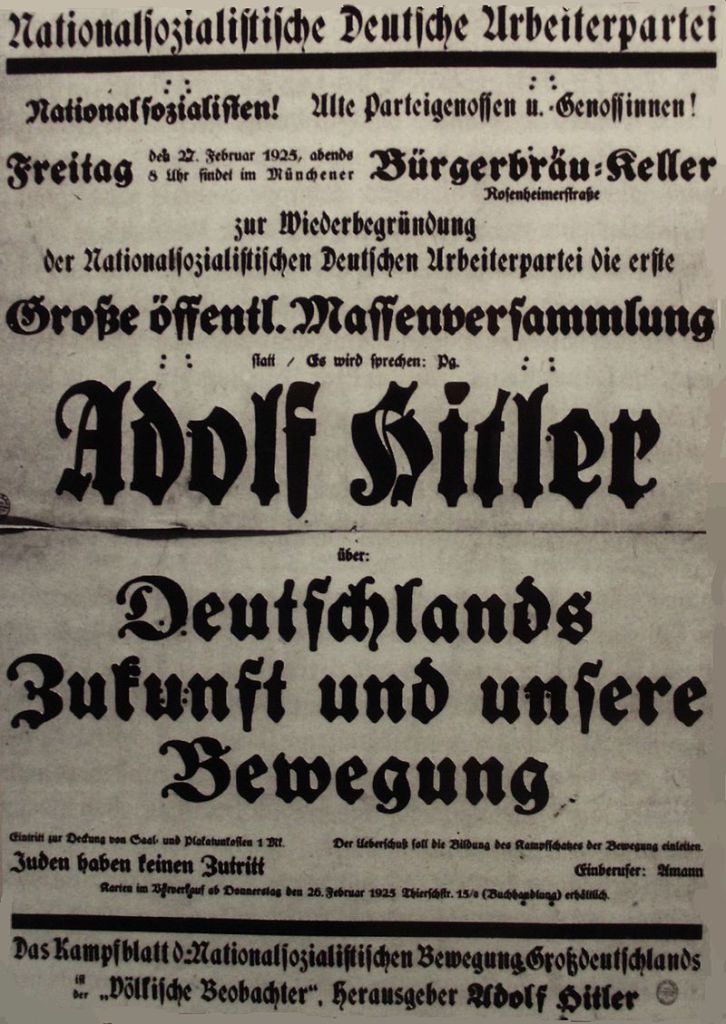

Back to the beer halls of Munich, not long after been released, Hitler was back in his old haunt – the Bürgerbräukeller Beer Hall, where he promptly officially ‘re-established’ the Nazi party on 27 February 1925. Not to be left out, during the war, Adolf Hitler delivered his infamous 8 Nov 1942, Stalingrad speech from Löwenbräukeller Beer Hall.

Images: Left – the notice to reestablish the Nazi Party at a ceremony at the Bürgerbräukeller and the Bürgerbräukeller Great Hall hosting a Nazi rally.

The Nazification of the Feldherrnhalle

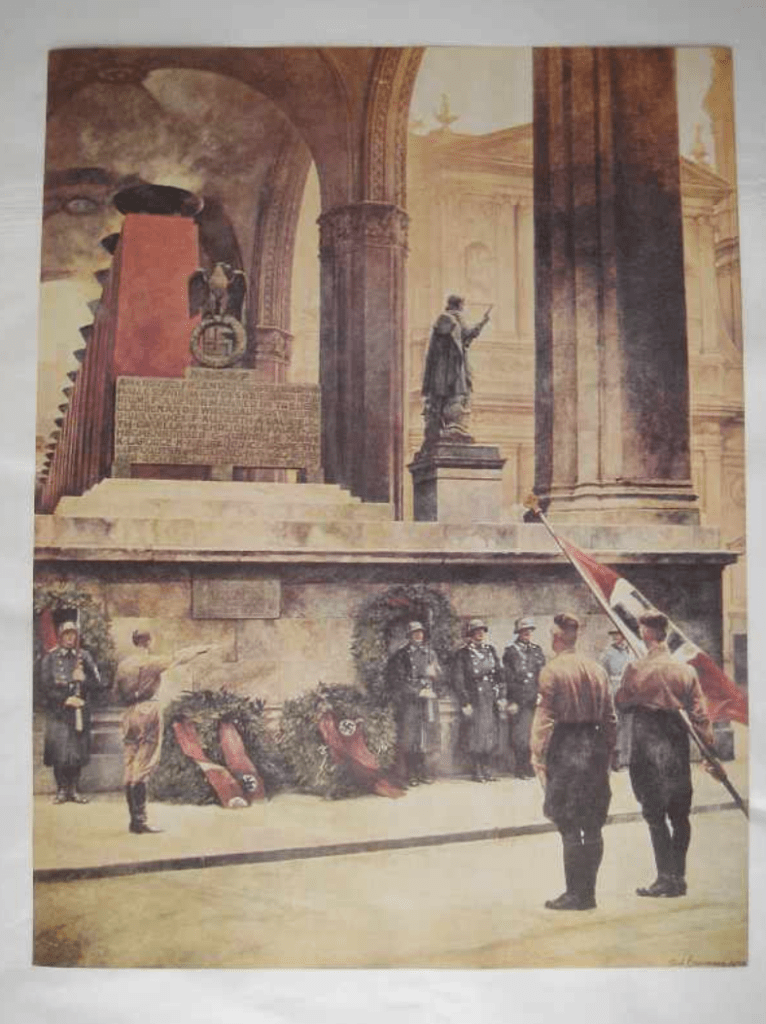

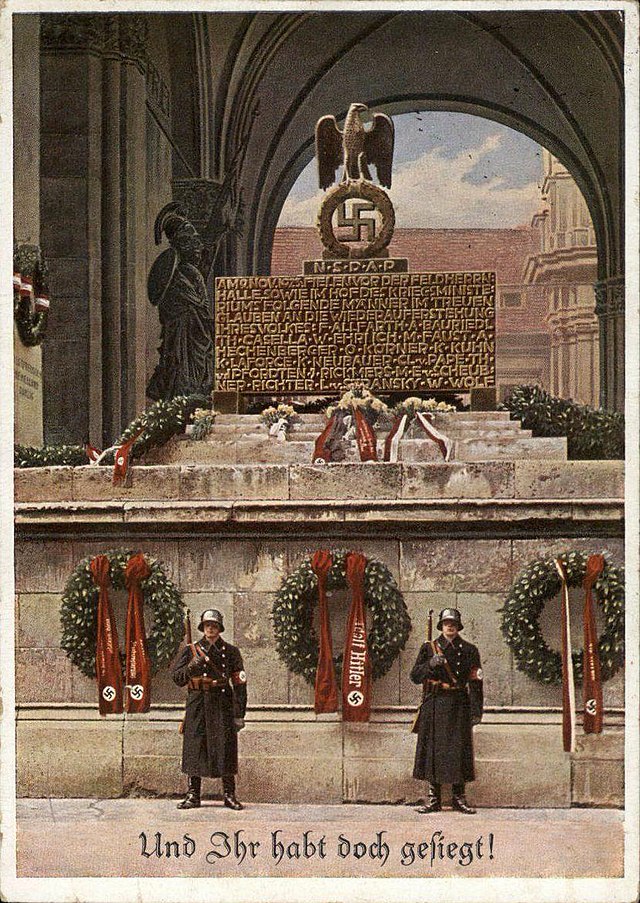

After the Nazis took power in 1933, Hitler turned the Feldherrnhalle into a memorial to the Nazis killed during the failed putsch. A memorial to the fallen SA men was put up on its east side, opposite the location of the shootings – crowning it with a Swastika. A Nazi add-on monument was mounted, the Mahnmal der Bewegung (Memorial to the Movement), basically a rectangular structure listing the names of the Nazi martyrs faced anyone standing at the corner of Feldherrnhalle monument. The back of the memorial read Und ihr habt doch gesiegt! (‘And you triumphed nevertheless!’). Around it flowers and wreaths were laid.

This memorial was under perpetual ceremonial guard by the SS. The Odeonsplatz square in front of the Feldherrnhalle was used for both SS parades and commemorative rallies. During some of these events the 16 Nazi dead were each commemorated by a temporary pillar placed in the Feldherrnhalle topped by a flame. Many new SS recruits took their oath of loyalty to Hitler in front of the memorial.

Passers-by were expected to hail the site with the Nazi salute. Those not wishing to salute, used a detour lane to by-pass the memorial and honour guard, sarcastically earning its nickname “Drückebergergasse” (meaning the ‘shirker’s lane’).

On 9 November 1935, the 16 Beer Hall Putsch Nazi dead were taken from their graves and to the Feldherrnhalle. The SA and SS carried them down to the Königsplatz, where two Ehrentempel (‘honour temples’) had been constructed. In each of the structures eight of the dead Nazis were interred in a sarcophagus bearing their name.

The 16 Beer Hall Putsch Nazi dead were regarded as the first ‘blood martyrs’ of the Nazi Party, and here’s where the Blutfahne – the ‘Blood Flag’ would make its appearance. It was brought out for the swearing-in of new recruits in front of the Feldherrnhalle and the taking of their oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler specifically. It was also brought out for Der neunte Elfte – 9 November, literally ‘the ninth of the eleventh’ or 9/11 (not to be confused with the current 9/11 Twin Towers commemoration) and it became one of the most important dates on the Nazi calendar.

Notably, the chosen day to celebrate the Putsch is not the 9th November, when the 16 Nazi martyrs were killed, it was the 11th November – the day Hitler was arrested – so to his megalomaniac mind the more important date as his personal arrest signalled the end of the Putsch (never-mind Göring and others who were still at large).

Every year the Putsch would be commemorated nationwide, with the major wreath laying event taking place at the Feldherrnhalle. On the night of 8 November, Hitler would open the ceremonies and address the Alte Kämpfer (‘Old Fighters’ – veterans of the Putsch) in the Bürgerbräukeller Beer Hall.

The Blutfahne – the ‘Blood Flag’ was treated as a sacred object by the Nazi Party and carried by SS-Sturmbannführer Jakob Grimminger at various other Nazi Party ceremonies. One of the most visible uses of the flag was when Hitler, at the Party’s annual Nuremberg rallies, touched other Nazi banners with the Blutfahne, thereby “sanctifying” them. This was done in a special ceremony called the “flag consecration” (Fahnenweihe).

Image: Hitler behind the ‘Blood Flag’ performs a ‘flag consecration’ on a SS Banner.

Rather mysteriously, and its akin to any good ‘who done it’ mystery – the Blutfahne was last seen in public at the Volksstrum induction ceremony on 18 October 1944, thereafter it vanished, which for such a significant artefact and ‘national treasure’ remains a puzzle. Its current whereabouts are still unknown.

Throughout the Second World War, the 9/11 anniversary ceremony continued, propagandists pitched the 16 fallen as the first losses and the ceremony was an occasion to commemorate everyone who had died for Nazi Germany – the ceremony now akin in Nazi Germany to what is 11/11 today and the Whitehall Cenotaph parade. As the war went on, residents of Munich came increasingly to dread the approach of the anniversary, concerned that the presence of the top Nazi leaders in their city would act as a magnet for Allied bombers.

Images: Original colour images of the German 9/11 anniversary parade in front of the Feldherrnhalle monument on the Odeonsplatz town-square.

The End

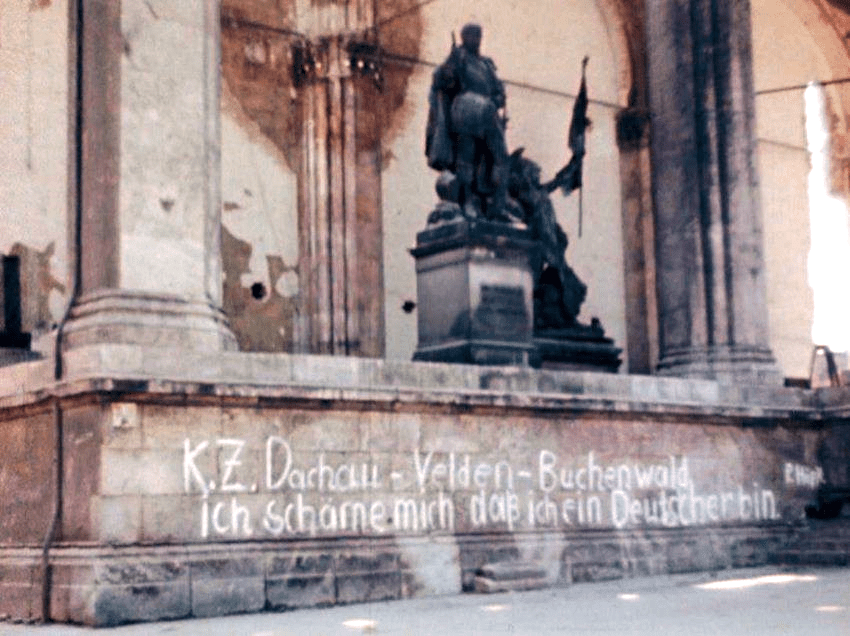

Understandably the memorial was going to cause considerable controversy at the end of the war, and it did. Local Munich residents angrily and spontaneously smashed the Mahnmal der Bewegung to pieces on the 3rd June 1945. It was also famously defaced when a guilt ridden German painted graffiti on the memorial with the words “Concentration camps Dachau – Velden – Buchenwald, I am ashamed that I am a German.”

However it remains a site for Nazi pilgrimage, and even as late as April 1995, a World War 2 Veteran named Reinhold Elstner, took the opportunity to commit self-immolation suicide in front of Feldhernhalle to protest against “the ongoing official slander and demonization of the German people and German soldiers”. Each year neo-Fascist/neo-Nazi groups from various European countries and Germany itself try to hold a commemorative ceremony for him, which Bavarian authorities constantly try to prevent through state and federal courts.

So, very understandable the need to sanitise this memorial and discourage neo-Nazi and neo-Fascist groupings from using it to honour an ideology that provided such significant misery to millions of people. But I can’t but think there is no point sanitising it completely as has been done, use it to educate rather – at least an information board or story board which explains the tyranny the site once fostered, a lesson to humanity not to do it again, maybe even Holocaust Memorial sanctioned tour guides to balance and educate and do away with the freelance cowboys (maybe they’ve done it, but that was not the case when I was last in Munich) – lest we completely forget, lest the ‘blood flag’ suddenly re-appear from its secret stash and we open up more ‘clean’ space in which Neo-nazism and holocaust denial/conspiracy theory can thrive (there’s no ‘proof’ to see now, moving on – its been removed, so prove it).

The same can be said of South Africa, at what point do we decide to allow WOKE thinking to remove all ‘white’ history and scrub that culture on the basis of the evils of Apartheid and Colonialism – too offensive to the majority. Take down ALL the statues, another … “where have all the statues gone”.. rather initiate the Communist and Revolutionist zeal for the ‘Year One’ calendar, and let’s all start our history from 1994 shall we comrades. No, history is history, warts and all, we need to ‘have the conversation’ at least, it’s the lesson to mankind to know where it comes from and therefore to know where it’s going to, it gives us our moral north .. sanitising it moves the compass south.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens