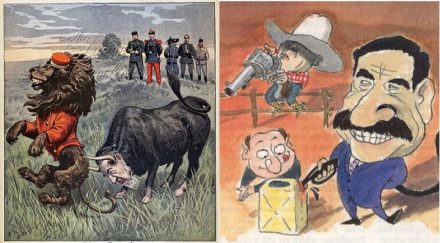

The path to the South African War (1899-1902) i.e. Boer War 2 is often misunderstood – so let’s look at the actual military numbers and the mission creep. Very often on Boer War social media appreciation sites you hear this old myth “the British intended to invade the Boer Republics and built up their forces on the borders to do so”. This build-up of British invasion forces then prompts the Boers to make “a pre-emptive strike” to “take up forward defensive positions” on British territory. The Boers didn’t start the war see! They merely forestalled the inevitable warmonger, none other than the greedy British – get it?

Problem is “I don’t get it”, my training as an Economic Historian will always lead me to look at the statistics and the ‘cold facts’ to make comparisons and conclusions, my training as a military officer will also always lead me to the science of military doctrine in analysing military history, and not a ‘mainstream’ historian’s interpretation of it. As to above assertions on invasion body troop strengths and pre-emptive strikes, let me be upfront – it’s all bunk, a complete myth and it not supported by the historical facts of the day, nor is it supported by military doctrine (then and now) and the cold hard facts – the statistics, ratios and numbers certainly don’t support it . This is again where ‘economic history’ starts to rip ‘political’ history apart, the numbers – the hard facts (measurable and accurate) start to talk and the political bollocks start to walk, and here’s how.

Looking at the numbers

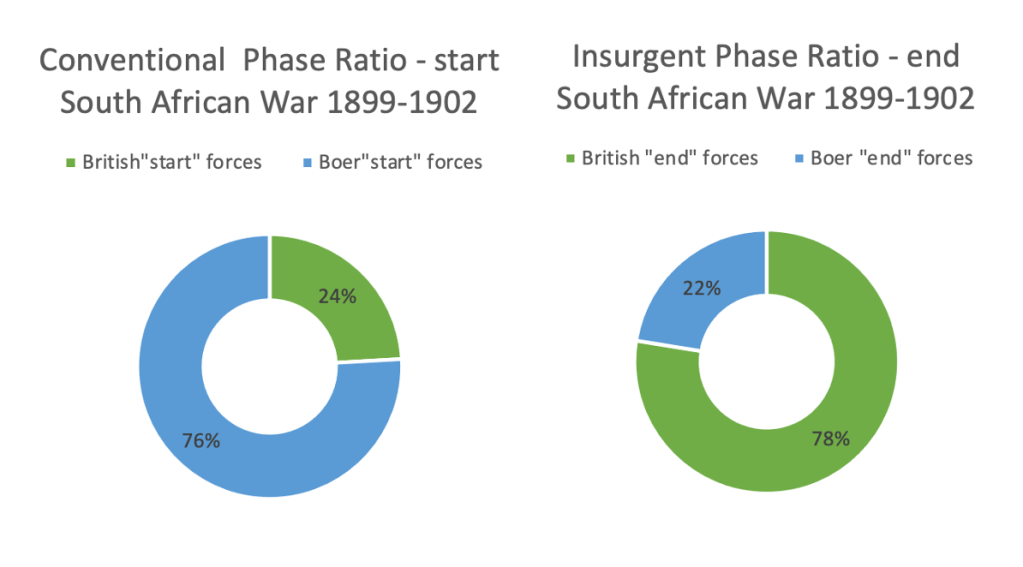

So, here the numbers to the start of the Boer War on the 11th October 1899 when the Boers invade sovereign British territories:

31st July 1899 – Total British Forces in the Cape Colony, Natal, Rhodesia, and Bechuanaland (Botswana) and Protectorates = Total 8,803 men.

1st August 1899 to 11th October 1899, additional British Forces arrive = Total 6,500 men

Total British Forces in the field as at 11th October 1899 = 15,300 men

27th September 1899 – Transvaal Mobilises Forces = 26,871 men

3rd October 1899 – Free State mobilisers Forces = 21,345 men

Total Boer Forces in the field as at 11th October 1899 = 48,216 men.

The Boer forces at the commencement of hostilities when they declare war against Britain are heavily in their favour = Boer Forces outnumber the British 3 to 1.

“On the high seas” as at the 11th October 1899 are an additional 7,418 British Troops on their way to South Africa – called up to bolster an inadequate British force strength in the event of war.

Even with their arrival at the end of October 1899 (after the war has been declared) bringing the British number up to 22,708 – British Forces are still woefully inadequate, and the invading Boer Forces still outnumber them 2 to 1.

There are numerous quotes and historic references which prove the British had no intention of ‘invading’ the Boer Republics, these always result in a slinging match whilst Boer romantics profess to intelligence reports as proof positive of a plan of attack. Like any military with a military academy and a war office, a scenario plan was devised by the British, its called ‘The War Office Plan’ and it was developed in 1886 – it outlines that should the British invade the ZAR, a full Army Corps (invasion force) would assemble at Colesberg and invade the underbelly of the OFS on their way to the ZAR, avoiding mountainous defences completely and just move up the spine of South Africa over flat and easy terrain (more or less the route of the N1 today).

In reality the British made no actual invasion plans, scenario ‘top draw’ plan yes, actual plans a ‘campaign plan’ with start lines showing troop strengths, regiments and units, timelines and objectives – no, that plan doesn’t exist – an entire Parliamentary commission and Royal inquest was made in 1902 after the war ended, and they established that “no plan for campaign ever existed for operations in South Africa” (that they meant an actual operational plan), but you can put all that aside and let’s just look at the numbers.

There is simply no way, that the British intended to ‘invade’ with a force of only 22,700 troops – going up against a 40,000 strong invading Republican Boer army – just no way. Anyone whose served in the military and understands military doctrines knows, you need twice the numbers of the opponent, at least 2:1 (ideally more) before commencing with an invasion. That means Britain would have needed at least 80,000 troops (in excess of an Army Corps) in theatre before it posed any threat as an ‘invasion’ Force. It had nowhere near those numbers, and nor did it intend to have those numbers. In truth – the Boer Army, who had twice the numbers of the British Army, posed far more of an ‘invasion’ threat – and that’s exactly what they did.

Also, so you can see how the ‘numbers’ and the ‘actual’ history correlate – Lord Milner writes to Her Majesty’s government and states that Kruger is unmovable on issues pertaining the Franchise, he warns them that the ZAR is gearing for an invasion of the British Colonies with the call-up of troops and purchase of munitions, and the purchase of state of the art rifles and artillery pieces – one million Mauser rounds alone arrive in Port Elizabeth as early as the 8th July (ordered around April 1899) destined for the Republics (well before the ‘impasse’ between Milner and Kruger).

He implores the British to send a sizeable force – a full “Army Corps” – of about 35,000 troops to bolster the small garrison forces in South Africa, warning them invasion of British colonies is inevitable.

The British War Office in London respond to Milner, they maintain that the ZAR was simply not bold enough to invade British sovereign territory, and on the remote chance that should an invasion take place, it would be a “farmers army” and could be held back by professional soldiers.

The war office also does not want to provoke a flammable situation by sending a full Army Corps. So, they bolster the garrison forces with only 6,500 men, including colonial ‘citizen force’ units mustered from the local populations – and an additional 7,400 men “on their way” from India – the doctrine again is that even though they are outnumbered they should be able to ‘hold the line’ long enough for an expeditionary ‘Army Corps’ to arrive. The war office estimates a ‘Army Corps’ will take four months to muster and would require a £1 million investment upfront – so not necessary unless there is an absolute and proven military threat.

The eve of war

By the end of September and the beginning of October 1899, Boer forces are amassing primarily at Laing’s neck on the Natal border and the ultimatum agreed by the Boers on the 27th September indicates that war is inevitable, presented by the 7th October 1899 to the British (4 days before they invade sovereign British territories), last minute attempts by Afrikaner Bondsmen in the Cape to get Kruger to “step-down” from his position fail, so too do last minute attempts by members of his own Raad and by his young appointed negotiator Jan Smuts in his final negotiations with Greene, even Steyn in the OFS is urged to get the ZAR to ‘step down’ – whilst all urging the ZAR to “step-down” – Kruger’s unbending demand that the 5 year ‘uitlander’ franchise would only come if the British tore up the 1884 London Convention completely and withdraw all her Suzerainty rights to the region, rights which have been in place since 1877 – this is now deemed a ‘step too far’ as it substantially compromised British paramountcy in the region. Kruger’s position remaining unchanged from the beginning of negotiations in June 1899 in Bloemfontein to the end – only with a cat and mouse game promising limited reforms and then withdrawing them in-between (more on this in an Observation Post called “for suzerainty sakes” as most people don’t understand the real Casus Belli of the war).

Kruger is superstitious, paranoid and impatient and doesn’t even wait for the presentation of the ultimatum to the British or the ultimatum’s deadline – he sees tiny troop movements of small garrison forces as the prelude of an invasion, albeit the British are by no means capitalised for such an invasion – they have not even called up their Army Corps at this point. But Kruger is on the warpath. On the same day the ultimatum is drafted – 27th September 1899 – D Day minus 14 days – Kruger telegraphed to Steyn:

“English troops already at Dundee and Biggarsberg, and will probably take up all the best positions unless we act at once. Executive Council unanimous that commando order should be issued to-day. We beg you will also call out your burghers. As war is unavoidable we must act at once, and strongly. The longer we wait the more innocent blood will be shed through our delay. We don’t intend to have Chamberlain’s note, with your amendments re Convention, telegraphed to you till burghers are at or near borders, and till you have been informed that the English Government has acted contrary to last part thereof. “We are justified in crossing border. Plan of campaign follows.”

27th September 1899 – D Day minus 14 days – Kruger telegraphed to Steyn again (same day again):

“Burghers will be in position in our territory near Laing’s Nek on Friday morning 5 a.m. All other burghers being called up to follow as soon as possible. Kock leaves with two cannons tomorrow evening, also big guns for Laing’s Nek. Will Free State then also be in position? Volksraad meets seven this evening. Can you reply by then? Plan campaign follows.”

On the 29th September 1899 – D Day minus 12 days – Kruger telegraph to Steyn:

“Our burghers going to hold positions on border to prevent enemy getting hold of them. You still seem to think of peace, but I consider it impossible. I am strongly of opinion that your people ought also to go to border to take positions. You think Chamberlain is leading us into a trap, but if we wait longer our cause may be hopelessly lost and that would be our trap.

In the final minute, with war inevitable and Boers amassing on the border to invade – the British Parliament approves the request to raise the ‘Army Corps’ as a deterrent against Boer aggression and they only start calling up their reserves from the 7th October 1899 – the Boers are already mobilised and its 4 days before the Boers invade. It’s too late, this force would only be arriving in critical mass in the South African theatre by mid January 1900.

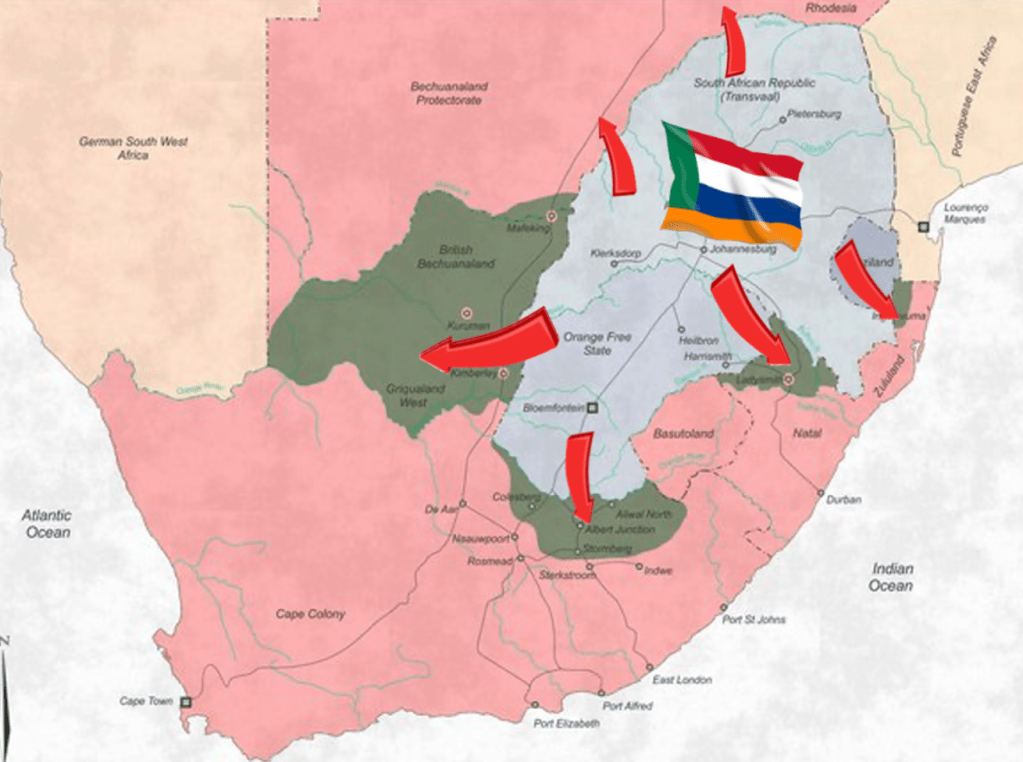

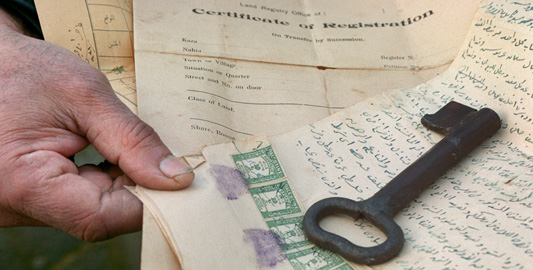

In the end, both ends of the British argument are 100% correct. Milner is 100% correct, the ZAR is a significant destabiliser in the area with territorial ambitions over Swaziland – which they annex, Rhodesia (the Adendorff trek and the Matabeleland concession) and Zululand for access to a Natal based seaport at St Lucia. President Steyn in the OFS also has territorial ambitions over Griqualand and the diamond fields in the Cape Colony.

Afrikaner Bondsmen and their supporters, men like Smuts, Botha, Hofmeyr and Reitz are all promoting the idea of a unitary Afrikaner Republic stretching from the Zambezi to the Cape. Both Boer preachers and politicians are all talking war and the removal of British influence from the entire region altogether (and Milner makes specific note of this). The two Republics are tooling up for war and the ZAR is commissioning and building massive defensive forts and buying advanced state of the art German and French siege guns. Vast stores of smokeless ammunition is been landed, and 40,000 brand new state of the art German Mauser rifles have landed – enough to arm nearly every Boer with not just one but two rifles. President Steyn has signed President Kruger’s long awaited “aggression pact” between the OFS and the ZAR on the 22nd March 1897 which locks the OFS into war even if the ZAR feels “threatened”. Simply put, the ‘winds of war are blowing’.

The purpose for going to war can best be read in the final statements made by the main protagonists.

Francis Reitz, now acting as the ZAR’s state secretary after sending the final Boer ultimatum, concludes his speech on the eve of war with the following:

“…. from Slagter’s Nek to Laing’s Nek, from the Pretoria Convention to the Bloemfontein Conference, they have ever been the treaty-breakers and robbers. The diamond fields of Kimberley and the beautiful land of Natal were robbed from us, and now they want the goldfields of the Witwatersrand … Brother AfrikanersI The day is at hand on which great deeds are expected of us – War has broken out ! What is it to be ? A wasted and enslaved South Africa or – a Free, United South Africa?”

So, for Francis Reitz accuses the British of breaching the spirit of Transvaal’s Suzerainty, accuses them of stealing Natal and Griqualand and a threat to Boer paramountcy in the region – calling for a ‘United South Africa’ (I.e. the Afrikaner Bond’s ‘Zambezi to the Cape under a Boer hegemony’ objective).

The desire of the Boers and the desire of the British that South Africa fall under their respective paramountcy and hegemony is a clash of interests between Boer Imperial and British imperial desires on territorial expansion and control – and this is the conclusion reached by just about every Boer War historian worth his salt as the basic underlying cause of the war, it’s the Casus Belli.

This paramountcy and desire for regional control by Boer and Brit respectively is most adequately wrapped up by Jan Smuts’ final word on the matter, when on the eve of war writes:

The aim of the war is to establish “a United South Africa, of one of the great empires (rijken) of the world… an Afrikaans republic in South Africa stretching from Table Bay to the Zambesi”.

On the British front, Joseph Chamberlain concludes his speech to Parliament on the eve of war with the following:

“… we are at war now because the oligarchy at Pretoria … has persistently pursued, from the very day of the signing of the Convention of 1881 down to now, a policy which tended to the evasion of its obligations; a policy by which it has broken its promises; by which it has placed, gradually, but surely, British subjects in the Transvaal in a position of distinct inferiority; by which it has conspired against and undermined the suzerainty, the paramountcy which belongs to Great Britain.”

So – for Chamberlain, the spirit and agreement of the Transvaal’s Suzerainty (its status as a vassal state as prescribed by the Pretoria and London conventions) has been breached – a breach of treaty – and in so a threat to British paramountcy in the region.

The British War Office is also 100% right, they’ve matched the ‘risk’ perfectly, in terms of military doctrine they augment their forces just enough to prevent total calamity, and its seen upfront in the invasions when these small bordering garrison forces – of professional officers and men, completely outnumbered in Ladysmith, Kimberley, Kuruman and Mafeking make quick work of the invading Boers and stop them in their tracks – on the 14th October 1899 the Boer attack on Mafeking is effectively driven off, and on the 20th October the British forces in Natal are successful at the Battle of Talana Hill and the next day on the 21st October they are successful again at the Battle of Elandslaagte .

On the 25th October the second Boer assault on Mafeking is driven off and on the 9th November, the Boer assault on Ladysmith is effectively driven off (albeit with heavy losses), the Boers then opt to put the town to siege. The siege of Kimberley starts in earnest on the 4th November with the British defenders firmly dug in, the Boers opt to shelling the town from a safe distance in the hope they capitulate. On the 13th November the Boer attack on Kuruman is successfully driven off and the Boers opt to put it that town to siege in addition.

The Pre-emptive strike and forward defences myth

As to a “pre-emptive strike” and “invading for the purposes setting up forward defensives” argument to forestall an inevitable British invasion so often found on Boer war appreciation sites – this is possibly the most stupid assertion and myth generated around Boer War 2 … ever, and for the following reasons:

Upfront, a ‘pre-emptive strike’ is not the plan, never is the plan. These modern-day Boer Romantics ‘couch commanders’ conveniently ignore people like the ZAR commander in chief, Piet Joubert – who states:

“The master plan was to advance rapidly on Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London and Durban”

Jan Smuts in his memoirs of the war refers to his direct planning to take the Port of Natal (Durban) in a rapid advance – a “Blitzkreig’ strategy.

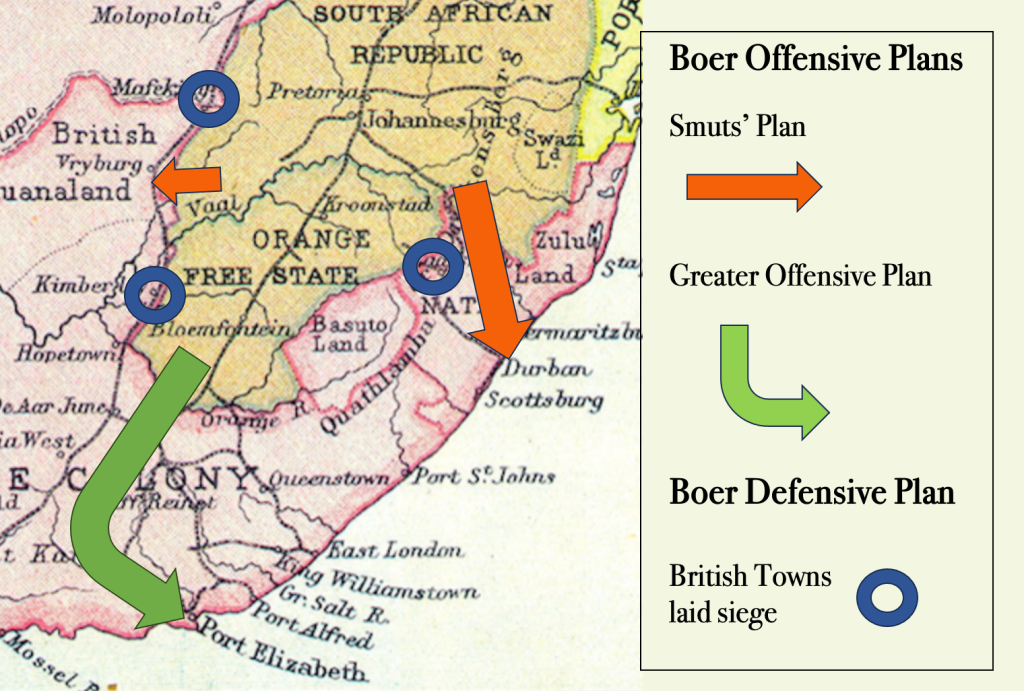

In fact, Jan Smuts is the only man with a plan. His plan is outlined, supposedly whilst he was sick in bed. It was presented to the ZAR raad (council) in a secret session and unanimously adopted. It’s a very specific plan, it is summed up by Smuts himself who said the plan was to invade Natal from Laing’s Neck and he does on;

“The republics must get the better of the English troops from the start … by taking the offensive and doing it before the British force in SA is markedly strengthened …. the capture of Natal by a Boer force together with the cutting of the railway between the Cape Colony and Rhodesia … will cause a shaking of the Empire”.

The idea of cutting the railway line between the Cape and Rhodesia is to create an uprising of Afrikaner support in the Cape Colony for the Boer Republic cause, Smuts in his account is very reliant on this happening, he’s an ex-Cape Afrikaner Bondsman, the Afrikaners in the Cape are the majority population – the idea of taking the Cape Colony would fail if they do not rise in support. Smuts’ objective through these actions – in Natal and the Cape Colony – is to “shake up” the paramountcy and in so force better terms with the British with a peace settlement early on … not to get into a protracted and costly war, and to do all this before any sort of “army force” or “expeditionary force” can be raised in the UK – an early concept of “shock and awe” and “blitzkrieg” is Smuts’ basic military plan. Smuts’ plan is also an early form of “manoeuvre” warfare – using the Clausewitzian concept (developed after the Napoleonic wars) – using superior and simultaneous advances along “exterior” lines (a concentration in space) on an enemy using “interior” lines (a concentration of time) of communication and supply. Smuts would also apply this later when he is tasked with forming the Union Defence Force in 1910.

Smuts’ offensive plan also does not propose laying anything to siege, surrounding and laying either Ladysmith, Kimberley or Mafeking is avoided entirely, he is far more concerned with speed and a quick win before Britain can reinforce anything – especially Natal and Durban which Smuts targets his ‘seat of war’. The rapid seizing of Durban whilst its relatively lightly defended is important to Smuts, without seizing it the British will be able to reinforce and counter-attack – so the taking of Durban will either make or break the plan.

So, here’s the Boer Republics’ offensive plan – in includes Smuts’ initial offensive plan and then a greater offensive offensive advance to Port Elizabeth so as to build on a Cape Afrikaner uprising and rebellion. At the start of hostilities on the 11th October 1899, according to Jan Smuts himself, the ZAR Commandant-General Piet Joubert merely had Smuts’ broad outline of the offensive plan in his hand, he had not given it any further thought – “no comprehensive war planning” had been done on how the strategic plan would be met by any planning on a tactical level or even on the operational level (contingency planning).

On launching the offensive, only then does the Boer leadership give thought to how they inited to meet Smuts’ strategic plan on a tactical level and operational level. They draw on inspiration from the first Anglo-Boer War, the Transvaal War of 1880 to 1881 i.e. Boer War 1, this war called for laying British garrisons around Pretoria to siege and then concentrating on using the natural mountain defences around Laing’s Neck on the ZAR/Natal border which squeezed the British ‘relief column’ making their way to relive the sieges onto a single road through the mountain defences – focusing them onto Majuba where the Boers enjoyed an outstanding victory. This reasoning had worked in 1881, no reason why it would not work in 1899.

So, as a defensive strategy to augment the offensive strategy, General Piet Joubert and the Boer leadership decide on laying siege to Kimberley, Mafeking (in the Northern Cape) and Ladysmith (in Natal) – their thinking is this would split the British forces who would then be focussed on relieving these border towns and their relief columns would have to follow singular roads and railway lines to get there, easy pickings for the Boers as they had done to them at Majuba – thereby weakening the British forces further and giving the Boer’s offensive strategy in Natal all the chance of success.

Important Note, as to military doctrine as follows;

“assuming a defensive posture does not win wars and a offensive strategy is essential for winning a war, defensive stances are a temporary measure allowing for an advantage to develop, which will eventually result in offensive action to secure combat success.”

Dr. D Katz’ ‘Jan Smuts and his First World War

Jan Smuts at this point is disillusioned with the Boer leadership’s planning, he feels this offensive and defensive plan is far too complicated and questions whether the Boers are capable of launching a plan of this magnitude. He even goes as far as calling General Piet Joubert “passé” and “hopelessly incompetent”.

The Boers however, initially follow exactly “the plan” in what they do. They advance from Laing’s Neck down the centre spine of Natal heading to Durban as planned, as they push into Natal the Boer Commanders telegram Kruger to say the “Vierkleur” would be soon flying over Durban. The ZAR Chief Justice Gegorowski boasted;

“the war will be over in a fortnight. We shall take Kimberley and Mafeking, and give the English such a beating in Natal that they will sue for peace”.

The general rally call amount the Boer soldiery is that will be “eating fish” in Durban, General Louis Botha convinced he will also be “eating bananas” in Durban. They also initially follow Smuts’ offensive plan in the Orange Free State, cutting the Cape Colony and Rhodesia railway line in the first action of the war at Kraaipan on the 12th October 1899.

Their mistake, they are too cautious and instead of using their much-promoted advantage – mobility, they err on a cautious and slow advance. The plan, as Smuts predicted is overcomplicated, and in so far as intending to split the British forces between the Northern Cape and Natal, the decision to put Kimberley and Mafeking to siege in addition to the offensive plan as a defensive plan also splits the Boer forces and weakens their offensive capability, from a ‘Blitzkreig’ (lightning mobility war) perspective they are unable to put their maximum effort behind their ‘schwerpunkt’ (heavy, focus – or centre point) which is the rapid invasion of Natal and the taking of Durban. The Boers also compromise their mobility and resources in Natal when they start to lay Ladysmith to siege instead of rapidly advancing to Durban.

In following “the plan” – the ‘high water marks’ of the invasions i.e., where they ultimately land up. In the Natal invasion it’s just 60 kilometres north of Pietermaritzburg – Botha stops at Mooi River, this invasion has no reference to the “defence plan” whatsoever (in fact it’s the opposite), and the Boers do not take up very effective “defensive positions” to stop any sort of mythical British invasion – the positions they take up are far worse than the positions they were in before they invaded. Any military person will tell you that Rivers and Mountain Ranges make for the most formidable defences – and in the case of the Boer Republics – the Orange River, Vaal River and Drakensberg are perfect defences – no need to invade anyone, investing in these border defences would have been the logical military doctrine, and far more effective as to a “defensive strategy” without initiating a war and the risk that involves.

Look at it from the perspective of military doctrine, the Boer “start line” is Volksrust on the border near Laing’s Neck – a most formidable defence position on the border of Natal and the “gateway” to both the ZAR and Natal, home to Majuba mountain and Laing’s neck, where the British were so soundly beaten by the Boers in 1881 – it’s a proven natural defence and one which the British could not breach just 18 years earlier.

As to continuing a deep advance (remember the offensive plan is to invade), after they are confronted by the British in the field at Talana outside Dundee on the 20th October 1899 (D Day plus 8) – the Boers are initially defeated in two pitched battles, the Boers are held up losing advantage daily. After winning the battle at Nicolson’s Neck the Boers manage to advance another 70 kilometres to Ladysmith reaching it on the 2nd November (D Day plus 24 days) – now they are now 190 kilometres into their advance from their start line on the border and nearly a month into their invasion campaign.

So, if your strategy is only one of defence – why leave such a formidable defence and find something else? Then as to the so called amassed “British threat on the border” – the invasion force overall Commander, General Piet Joubert is joined by General de Kock from the OFS and General Erasmus and they advance from their start line for nearly 120 kilometres deep into Natal territory before they meet any significant British forces or resistance whatsoever – the British are nowhere near the “border” and “poised” to invade anything. The British have rather inadvisably split their forces between Dundee and Ladysmith. Extending military supply lines and logistics support for 120 kilometres in 1899 using wagons and horses to initiate a “pre-emptive” strike aimed at the British in Dundee is pure Hollywood, wishful thinking, it has nothing to do with military doctrine or sound military planning – or even the Boer’s plan for what it is.

General Louis Botha then extends the advance from Ladysmith all the way to Mooi River on the 22nd November 1899 – 100 Km away from Ladysmith and 60 km from Pietermaritzburg and now a staggering 290 km from their start line. That’s the length of the “supply” line for the Boers – their “high water” mark. No military commander in his right mind sets up a “defensive position” with a near 300 km long supply line running through enemy territory intended to support ‘defences’ – no military commander in 1899 advances near 300 km on horseback for a pre-emptive strike either – air warfare has not been invented yet and even by today’s standards a ground force invasion 300 km into enemy territory is never considered by any commander as a mere “strike” – pre-emptive or otherwise.

The Boer high-water mark is only obtained by the 22nd November – D Day plus 43 days – now having been significantly compromised on mobility and speed. Both HMS Terrible and HMS Powerful had arrived in Durban port by the 6th November 1899, either one of these two Battle Cruisers had more fire power on board than the entire Boer invading armies combined – a Battle Cruiser defending a port from mounted infantryman on horseback is no match. The Royal Navy is Britain’s senior service and it has at its disposal the very best of all their resources and commanders, defending their ports is what the Royal Navy does best, they are very good at it.

The Boer invasion falters, it fails because they had lost their only significant advantage – mobility, aggression and speed gives way to cautiousness, they chose resource draining static warfare instead – sieges and invest into them instead, losing valuable days and sacrificing their “Blitzkreig” offensive plan altogether.

With Botha’s objective of “eating bananas in Durban” now completely dashed, General Botha has no choice but to do what countless military commanders before and after him have done when an invasion fails – and beat a retreat, creating what are known in the military as “defensive “boxes” as you go along, the idea is to slow the enemy’s counter attack down until you can “join” with more friendly forces and consolidate – which he initially successfully does just north of the high water mark at Willow Grange on 23rd November 1899 and then further north at his next “box” at Colenso on 15th December 1899. He finally settles further north on the Tugela heights as his next defensive box, having now retreated for 80 Km, however he loses this pivotal battle and his final defensive box to the British on the 27th February 1900 (to see a defensive box retreat in action in a more recent war involving South African Commanders – see “Gazala Gallop” in WW2).

On the western front, the Boers are able to invade the arid and sparsely populated northern Cape meeting no real resistance from any British forces – as none are stationed there in any numbers – the Boers end their high water mark at the border with German South West Africa – this has more to do with the strategic imperative of opening up a sea route and port access via Walvis Bay and linking up with a “friendly state” for the purposes of supply than it does with any offensive or defensive plan offered by the Boer command. It certainly has nothing to do with a ‘pre-emptive’ strike.

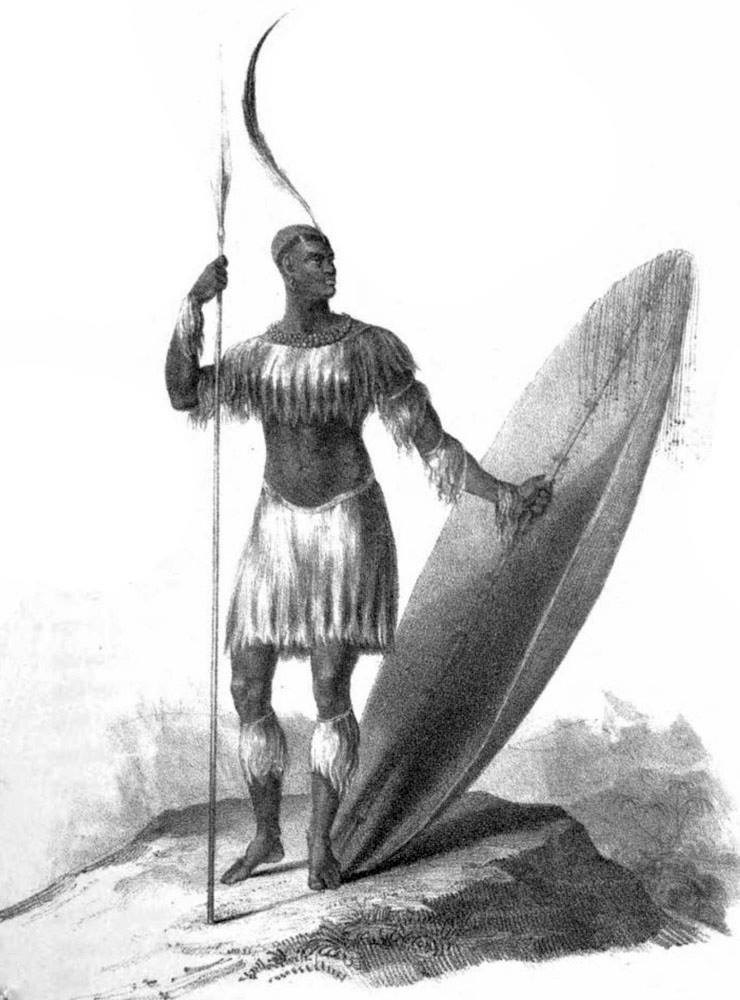

On other lesser known fronts

If there is any semblance of logic in invading the Cape and Natal colonies for the purposes of establishing forward defences only, there is absolutely no logic in the Boer invasions of Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Bechuanaland (Botswana) to suggest invading for purposes of defending – or even a ‘pre-emptive’ strike – the tiny nominal British Police forces in both these countries are no invasion threat whatsoever, and all the invasion of the Bechuanaland Kingdom does is bring the Tswana into the war as a belligerent all on their own, and the Tswana in their own right decimate the invading Boer Kommando and its laager at Derdepoort on the 25th November 1899. The small BSAP (British South African Police) base consisting of 450 British soldiers at Tuli in Rhodesia is however sufficiently professional to stop the 2,000 strong Boer Commando (now with a 1 to 4 advantage over the British) which had forged itself over the Limpopo River into Rhodesia at Rhodes Drift and other points. On the 2nd November 1899 the BSAP successfully halt them at Bryce’s Store and then repulse the invasion, although border incidents and Boer incursions into Rhodesia continue for some time – well into the Guerrilla phase.

What Defences?

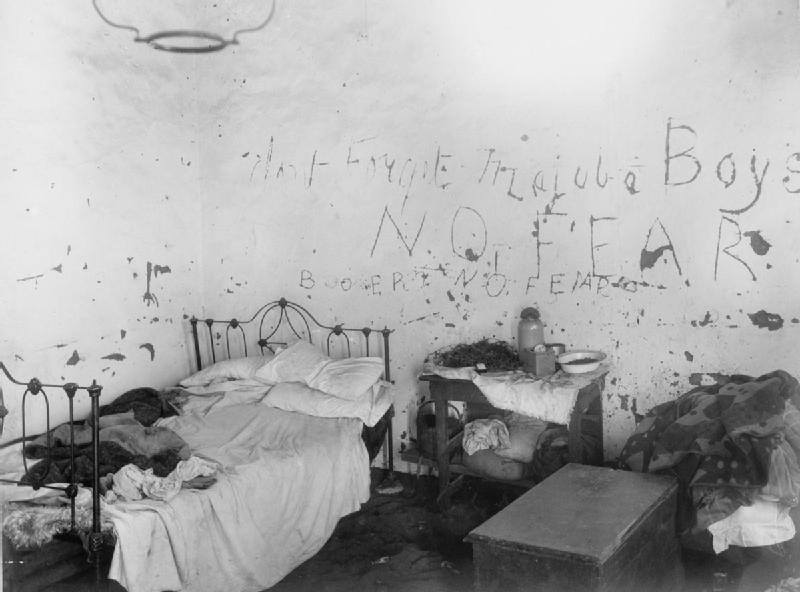

Also, nobody has been able to point where these so called ‘invasion for the purpose of defensive positions’ are, there is no investment in resources or materials for effective defences, the Boer trenching system at the Modder River at the beginning of the war in November 1899 are proven ineffective.

The defensive earthworks that make up the trench line at defence cluster centre at Magtersfontein is merely a shallow trench converted from a natural ‘donga’ at the base of the koppie range (refer Dr. Garth Bennyworth’s groundbreaking work on this trench-line) – the British frontal attack on this trench-line is successfully repelled by the Boers on 11th December 1899 (Cronje’s only real tactical ‘victory’), but after regrouping and reinforcing the British are able to by-pass these defences completely in a highly mobile flanking manoeuvre.

No large defence fortifications are really invested in by the Boers in either Natal or the Cape Colony, and any idea of fortifying the Republics borders are in fact neglected in the drive to invade the British colonies instead.

It is only from the beginning of the new year in 1900, that the British have been able to muster anywhere near enough troops to land in Cape Town, that they are now matched 1:1 to the Boer army, and it is on these equal footings that the British counterattack, breakout and relieve of all the major sieges. From January 1900 to July 1900 they rout the Republican armies from their colonies, relieve their sieges and in two significant manoeuvres – the Battle of Paardeberg on the 27th February 1900 and Brandwater Basin (Surrender Hill) on 30th July 1900 they break the Republican forces critical mass to fight a conventional war – Brandwater and Paardeberg alone result in the capturing 8,300 men and the Boer Army is now simply just no longer matched to the British on a 1:1 ratio, it’s now in an inadequate position – with more British troops streaming in.

The 500,000 myth

Often on Boer war sites, and even on simple things like wiki we see this statement “it took 500,000 British to defeat 20,000 Boers” – the much-touted ratio in this type of media is that the Boers were outnumbered 25 to 1, at a staggering disadvantage, but these plucky Boers held the mighty British empire at bay. Now that’s a figure designed to paint the Boer fighter as some sort of super-man and the British military as bumbling, monolithic and ineffective. But the truth is far from this and this figure is completely erroneous designed to drive Afrikaner nationalist political rhetoric – it has nothing to do with actual numbers on the ground.

Now, here’s the truth – at no point in Boer war 2 were there ever 500,000 British troops in South Africa as boots on the ground at any one point in time – in total, over the course of the war the British called up 550,000 men – that bit is true, yes. HOWEVER the British rotated their Regiments in and out of South Africa on ‘tours of duty’ – never really sending a full regiment into the operational theatre at once, retaining many at home and in their other colonies around the world. The “high water mark” i.e., the maximum number of British Troops in South Africa at any one point in time is 230,000 men. Even pro-Boer chronologies like that of Pieter Cloete’s Boer War facts and figures reluctantly has to admit this fact.

This high-water mark of 230,000 (including African Auxiliaries) is only peaked briefly during the Guerrilla Phase of the war – and at least 50,000 of these troops are being used to man the rather extensive blockhouse defence system stretching from the top to bottom and side to side across the whole of South Africa (as referenced by Simon C. Green in his Blockhouses of the Boer War) – over thousands of kilometers. On average during the Guerrilla Phase of the war – September 1900 to April 1902, the British enjoy 190,000 troops on the ground.

But let’s stick to the high-water marks for a proper account – the high water for the Boer forces, total Boer War – including 6,000 burghers who add onto the original ZAR and OFS Commando call-up, the statutory Boer forces, foreign volunteers and Cape Rebels is 87,365 men (possibly higher if we add African auxiliaries and rear echelon support). That means a realistic ratio between Brit and Boer at the high-water mark is a 3:1 ratio – total Imperial forces versus total republican forces. It’s a far cry from the emotionally and erroneously touted figure of 25:1.

If we want to account Boer War 2 properly and view it with balance, it would be correct and very true to say at the beginning of the war the Boers outnumber the Brits 3:1 – as the war progresses there is a juxtaposing of numbers… and by the end of war the Brits account 190,000 troops in country, Boers account 24,300 left in the field and 47,300 POW in the bag (factoring out the ‘Hensoppers’ and ‘joiners’) = 71,600 or a 3:1 ratio – Brits outnumber Boers, a reversal of the ratio the Boers enjoyed at the start of the war.

In terms of military doctrine, the above estimation is about right – to invade the British territory the Boers need a 3 to 1 advantage to be successful and to counter attack and hold the Boer territory the British need to be at a 3 to 1 advantage – and even by Guerrilla Warfare standards and the doctrine used to fight one, this number is very low. Consider the following:

American Brigadier-General Nelson Miles was put in charge of hunting down Geronimo and his followers in April 1886. Miles commanded 5,600 troops deemed necessary to find and destroy Geronimo and his 24 warriors. In Malaya in 1950 it took 200,000 British, Australian and allied troops to defeat 5,000 Communist guerrillas. In Ireland over the 30-year course of ‘the troubles’ a total of 300,000 British troops were used to contain 10,000 IRA guerrillas. Closer to home, so the arm chair Boer war generals get this – over the course of the Angolan Border War (1966-1988) and the ‘Struggle’ (1960-1994) the SADF would call up 650,000 conscripts and then hold them in reserve – MK and other non-statutory force ‘guerrillas’ at their high water mark in 1990 only have 40,000.

The modern-day theoretical ratio of counter-insurgency forces to guerrillas needed to defeat an insurgent/guerrilla campaign is 10:1. In 2007, the US Department of Defence produced a document entitled Handbook on Counter Insurgency which quotes this as the rule-of-thumb ratio for all such operations – and that is even with the advent of modern technology in warfare fighting mere insurgents or guerrillas. Little wonder that General David Petraeus needed 180,000 coalition force troops (the same size as the full invasion force) on the ground in 2007 just to deal with the Iraqi guerrilla “surge” spearheaded by an insignificant but determined bunch of suicide bombers.

Boer bashing and other myths

Military doctrine and planning – to anyone whose served as officer in a military, is made up of three levels – the Strategic level, the Tactical level and the Operational level (when the metal starts flying around and the rubber hits the road). Military Generals and Commanders are judged by how they relate these three components – Strategic, Tactical and Operational. German Forces during WW2 are outstanding at the Operational level, completely dazzling the enemy concentrating overwhelming firepower at the “schwerpunkt” – the ‘heavy or focal’ point. They are equally outstanding at the tactical level, consider the masterful work of Field Marshal Rommel in North Africa. But they fail at the Strategic level by overextending their resources and pandering to wayward political ideologies and ambitions – and that loses them the war.

In reality, and it’s not trying to be nasty or ‘Boer bashing’ in any way shape or form. The Boers at the ground level are a committed, determined, resourceful and extremely brave bunch. They are scarifying much and like the Japanese in WW2 have a deeply ingrained cultural sense of honour.

But their commanders fail these brave men on all three key aspects of warfare. At an Operational level they are been asked to use a Commando system of mounted infantrymen – good for quelling poorly armed native rebellions – but absolutely hopeless when confronting a modern professional military force with modern weaponry using both combined arms and joint arms in which they are very well versed – and it quickly shows when the British are able to repel the invasions and stall them long enough to get reinforcements in whilst completely outnumbered. The British ORBATS (Order of Battle) are also far superior in just about every key engagement fought – that’s a fact.

It is often noted in all the Battle ORBATS – even the ones that mark the beginning of the war in the conventional phase, that the Boers are always “on the back-foot” always “outnumbered” almost always fighting against the odds – even for battles they win. However, this is again a function of poor leadership – at the beginning of the war the Boers outnumber the British significantly, but they don’t make use of the advantage – instead of driving their forces to their “schwerpunkt” and the “crucible” (Natal) – focusing on their plan and leveraging their only real advantage – mobility, they choose instead to divide their forces and sacrifice their mobility completely. Inexplicably they commit unusually large numbers of these highly mobile combatants and all their resources to siege warfare (static warfare) and not to defeating the enemy in the field (also a key military blunder) – high numbers of Boers sitting around and simply shelling three British towns from afar – safely out of range, and other than Ladysmith, making no real attempt to ‘take’ the town – and in doing this they allow the British to pour in all the reinforcements they need to counter-attack.

On a tactical level, General Joubert – tasked with the invasion of Natal fails on nearly every level, he fails to take tactical advantage of his “mobility” and fails to “take the fight to the enemy”, he fails to prevent the British forces at Dundee from “linking up” with their forces in Ladysmith (a key military blunder), and he fails to take Ladysmith when the opportunity is presented to him on a plate choosing a divine sense of providence instead (another key military blunder). By the time General Botha takes over the advantage is lost, and Buller is able to ultimately dislodge Botha at Tugela Heights with the innovative use of pontoons and manoeuvre and relive Ladysmith.

General Cronje, on a tactical level on the other front in the Cape also fails on every level, he fails in his initial defences, fails to move from his static defences in time, sacrificing mobility again and is outflanked and outmanoeuvred by a more “mobile” General French, Cronje then, for reasons known only to himself fails to link up with General de Wet and presents himself as a sitting duck to the British – the result is the 1st significant capitulation of Boer forces at Paardeberg on the 27th Feb 1900.

General Christiaan de Wet also fares no better. De Wet’s attack on Wepener is strategically un-sound, committing resources to worthless target and he’s repeatedly beaten back by a gutsy small garrison force. His plan to defend the indefensible at the ‘Brandwater Basin’ is flawed and he too presents his forces as sitting ducks in a ‘pocket’ surrounded on all sides – and then he leaves his command post on the “first train out of Dodge” as the British close in on him and leaves his squabbling subordinates and troops to fight it out instead, the result is a complete breakdown of his command and the 2nd. significant capitulation of Boer forces at Surrender Hill on the 30th July 1900.

This surrender marks the start of the Boer’s loss of the war (it’s the beginning of the end), they are unable to recover it and the surrender marks the end of the Conventional War and chalks it up as a British Victory. Often put up on a pedestal as a “volksheld” (people’s hero) unfortunately General Christiaan de Wet has the stigma of losing the Boer war for the Boer nation – it happened under his watch and his Command – literally. Militarily speaking he’s directly to blame – and he fares no better leading a doomed, inadequately armed, inadequately supported, strategically flawed, and failed Boer Revolt in 1914.

De Wet’s invasion of the Cape Colony in the guerrilla phase is also a disaster as he signals his intentions up-front to the British and over commits a slow and large wagon train which the British chew up and then they expel de Wet from the Cape with a semblance of his invasion force left over and the loss of most of his transports. Tactically de Wet is brilliant, evading his ‘hunt’ and labelled ‘The Boer Pimpernel’ - romanticised somewhat, especially his tactical victory using barefoot burghers to sneak up on the British at Groenkop. However truth be told, on both an operational and strategic level, as a commander he fails, even his victory at Sanna’s Post is somewhat flawed as an ‘own goal’.

On a strategic level, as we have seen Smuts’ strategic plan adopted by the Boer Forces is thrown out the window almost from the get-go. They start with it, but simply do not follow through with it at all, invading three British colonies and two British protectorates, splitting focus and forces – completely misreading and unable to raise the critical “Cape Rebellion” and completely sacrificing the Blitskreig concept by working to all their weaknesses and not any of their strengths. Smuts’ “Clausewitzian concept” goes out the window too – in the Conventional War phase, the Boers sacrifice their superior and simultaneous advances along “exterior” lines (a concentration in space) and revert to only using “interior” lines (a concentration of time) for communication and supply.

In terms of strategy, on a political front, Kruger’s decision to strike out, by any type of military action you care to mention, against the world’s single biggest superpower, one whose Navy is bigger than the French, German and American Navy’s combined, at the very height of its Imperial power, is fundamentally flawed – plucky and very brave, yes – but strategically myopic and very unsound.

The best the Boers can do from here out is a ‘hit and run’ guerrilla campaign in the hopes of wearing the British resolve down to avoid “unconditional surrender” and get better peace terms (which eventually happens). The ‘Bittereinder’ guerrilla campaign is not fought with any romantic idea of actually “winning’ the war”, the Bittereinder Generals – Smuts, Botha and de la Rey are under no illusions, they also see the resolve of their women to endure the farm clearances and concentration camps as their duty in winning a better peace – they never, during or after the war, turn to victimhood, its denies them their pride and their sacrifices. The victimhood argument is a latter day ‘politics of pain’ concept taken up by latter day “pure” Afrikaner nationalists, nearly all of whom sat out the war or were too young at the time.

Even the decision to strategically engage Guerrilla War is unsound given the extreme sacrifice of lives and livelihoods required to run this type of campaign, literally breaking the back of the Boer nation – the folly of this thinking is something even General Botha realises, and he sues for peace before his entire nation is crushed – as in his own words there will be literally nothing left to fight for.

This is not the failure of the Boer soldier – this is the complete failure of the Boer Command. As military historians we have to look at the ‘score card’ in an objective and disparaging way – pointing out “critical failures” in doctrine it is – “boer bashing” it is not.

The Score Card

To look at the Boer war by way of its score card we need to divide it into three broad sections – the Conventional War – Phase 1, when the Boers have the advantage, the Conventional War – Phase 2 when the British have the advantage and then The Guerrilla War (Insurgency) phase – which needs to be separate as the edicts of war change completely.

In all, for the duration of the war there are 170 significant actions fought between the Boers and the British (including their allied Black armies like the Tswana and the Swazi), these include significant pitched conventional battles, relief or success of all sieges, successful or repelled attacks and counter-attacks during all phases on strong-points (blockhouses, bases, forts) and trains, and the taking of key cities by way of military objective – Bloemfontein, Kroonstad, Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Not factored is the general carnage of destroying property – by either British or Boer actions – the Boer actions of burning down ‘British’, ‘hensopper’ and ‘joiner’ farms, ransacking and looting towns (Dundee etc.), destroying mission stations and blowing up railway track are excluded – so too is the carnage caused by the British burning down ‘bittereinder’ farms, destroying livestock and blowing up buildings. Trying to even factor this would be impossible.

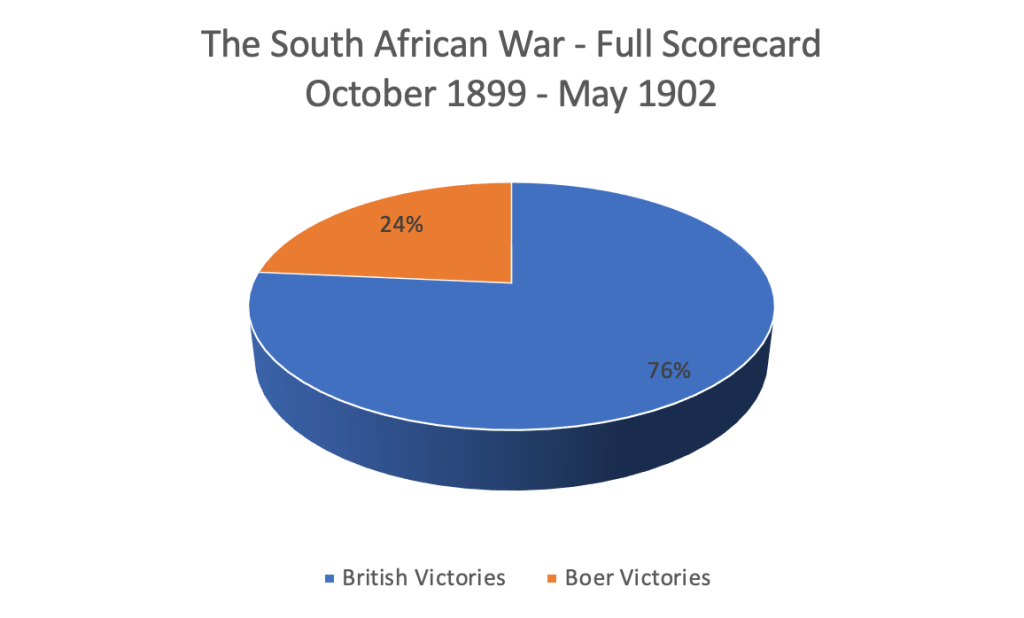

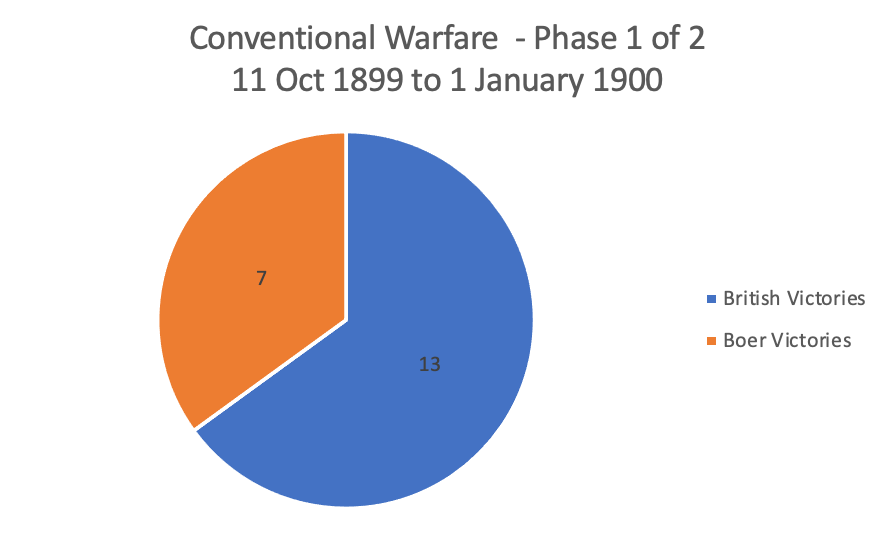

From the 11th October to 1st January 1900, the Boer forces have a numeric advantage, however the British battle order stemming and repulsing attacks on besieged towns is very good considering their disadvantage, so too the initial advance to relieve Kimberley – during this period 21 actions are fought – the Brits win 14 and the Boers win 7.

From 1st January to July 1900, the numeric components start to balance, however on a Operational and Tactical level conducting conventional combined arms – the advantage swings significantly to the British. All the major sieges are relieved, the Boers invasions are turned and they are ejected from the British colonies. The hunt into the Orange Free State decimates the fighting capability of the Boers and forces the surrender of their conventional fighting capability. During this phase 49 actions are fought – the Brits win 44 and the Boers win just 5.

Overall, for the ‘Conventional’ war phase, the balance is overwhelming in favour of the British – British win 58 and the Boers win 12. In terms of timing, the British victory in the Conventional Phase is swift – from October to July – a mere 10 months, they have reversed an invasion, captured two separate countries, taken both Boer Republic’s capital cities, taken the Boer’s economic hub, isolated both countries and starved them of external aid. Broken the critical mass of the enemy to fight conventionally, taken nearly every major gun and artillery piece, and occupied all the enemy’s fortifications and defences. By any military standards that is good Command – Strategic, Tactical and Operational.

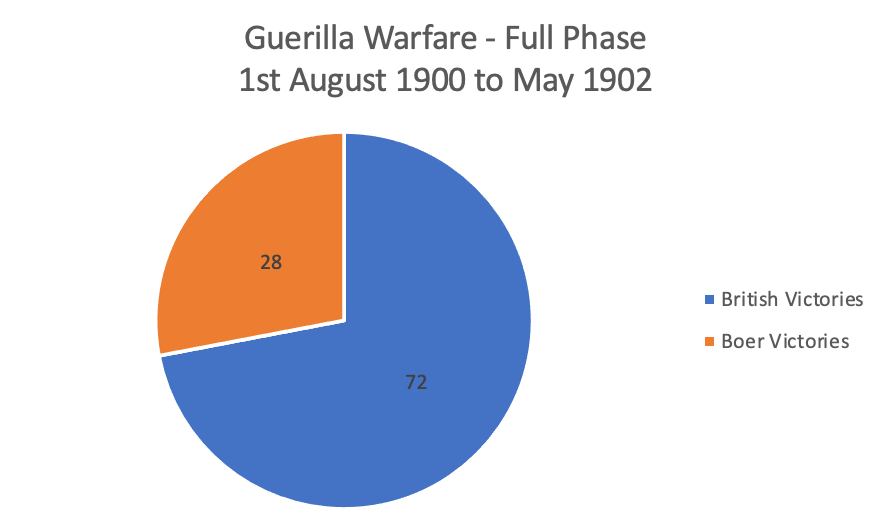

The Guerrilla phase is completely different, there are no significant pitched battles, battles resemble skirmishes, sieges are small towns remotely accessed and the focus switches to destroying supply lines (Boer and Brit) and ‘Commando’ hunts. It’s a “slow burner” in other words not much happens for months on end for the hundreds of thousands of troops in the theatre of operations, truly a case of “war is 99% boredom and 1% terror”. From August 1900 to May 1902 – the duration of this phase – 22 months, 100 significant actions are fought that would classify a ‘clash of arms’. It works out to only about 4.5 direct classes between Boer forces and British forces per month.

The scorecard is also in favour of the British – the Brits win 72 and the Boers win 28. To read this correctly we also need to understand that the Boer strategy in this phase is not to beat or capture British troops (they can’t keep them), generally the strategy is to harass the British, inflict some damage, retreat and fight another day. On a ratio of Brit to Boer “wins” the ratio is 2:1 – the Boers are remarkably successful at insurgency warfare, and they generally evade the ‘hunts’. The Boers do well at the tactical and operational levels and attain their objectives of wearing down British resolve and elevate their monetary and human costs of waging war – but it comes as a massive cost to the Boer lives and livelihood at the strategic level.

For the British, they win at the strategic level, the objective of starving the Guerrillas of their supply – food, ammunition, transport, weaponry, shelter and human resources, not to get into the moral or ethics of this, this is strategy used to win just about every Guerrilla war ever fought, by Britain or anyone else – it was the focus of the Vietnam War, the South African “Border War” and even most recently the Afghanistan War. On a tactical level their ‘Counter Insurgency” measures – now known as COIN – are very successful, so much so the Boer War’s Guerrilla Warfare phase is the shortest fought Guerrilla War in modern military history.

That said, as Professor Abel Esterhuyse rightly pointed out to the Observation Post – by 1902, the Boers emerge as the masters of ‘Insurgency Warfare’ and the British emerge as the masters of ‘Counter Insurgency Warfare’ (COIN) – lessons that are still referenced at Westpoint Military Academy to this day. This mastery would also define the ‘South African’ way of fighting war, when Jan Smuts is tasked with amalgamating the Boer Commandos and the old British colonial regiments to form the South African Union Defence Force (UDF) in 1910.

Thus, the UDF was built along the lines of using effective combined arms with high degrees of mobility to deal with both conventional warfare (as is the requirement of any statutory force) in the event a Colonial Power in Africa (e.g. Portugal or Germany) invades the Union and any domestic insurgencies (initially ‘internal’ threats are defined as potential Black African uprisings) and the UDF COIN doctrine is been developed to counter-act it along with a ‘Seek and Destroy’ ethos.

Smuts is happy to cherry pick, basically he’s happy to bring all that’s great and good about the British culture of warfare – their discipline and drill (sorely lacking in the Boer army), their uniforms and rank structures (sorely lacking in the Boer army) and their very effective use of combined arms warfare and joint arms warfare (also sorely lacking in the Boer army) and combine it with the Boer culture of warfare – the use of mobility, and applying high rates of survivability thinking to tactics of assault and defence (both of which are sorely lacking in the British army).

Smuts will build into the UDF the doctrine of highly mobile ‘combined arms’ – mainly the effective use of mounted infantry, armour and artillery (and other ‘arms’) all acting in unison and speed. Finally, he’s able to implement the doctrine of “manoeuvre” using the Clausewitzian concept. Under General Jan Smuts the UDF was shaped into a very effective fighting force, one that is far ahead of the old Boer Republics strategic and tactical constructs and doctrine. This will have far reaching consequences as this South African ‘philosophy’ of warfare would be effectively applied from the 1st World War (1914-1918), to the 2nd World War (1939-1945) to the ‘Border War (1966-1989) and its still used by the SANDF to this very day.

Casualties

The number of casualties in the Boer War needs a whole new Observation Post, as here we look at the very sensitive subject of civilian casualties – Boer, but also British and Black – the number is extreme – about 50,000 and still rising given new research – nearly all of it the result of disease – Measles and Typhoid mainly. The Measles epidemic, which swept the ‘Black’ and ‘White’ Concentration Camps and the besieged British citizens – killed nearly 40% of all the civilians succumbing to disease – measles as a ‘children’s disease’ especially taking its toll on Boer children. Not just civilians, the biggest killer of British soldiery was Typhoid and not the Boer’s bullets, nearly two thirds of all British casualties are the result of disease – young fit men who are dropping like flies from the same diseases sweeping the concentration camps and British towns under siege. Typhoid alone affects 57,684 British soldiers – killing 8,225 of them.

This is a highly sensitive and misunderstood aspect of the war – it requires a full analysis on the disease bell-curves and medical science to fully properly understand the causes and effects, and actions taken or neglected – look out for a future Observation Post in draft called “The Boer War’s biggest killer” where we will deep dive this subject and these statistics – because if there is one “winner” of this war’s butchers bill it’s not the British or the Boers – it’s an indiscriminate cocktail of micro-organisms.

We also need to look at the Killed in Action (KIA) and Died of Wounds (DOW) and survivability ratios between Republican and Imperial forces, as the KIA/DOW figure for the Brits is around 8,000 and the KIA/DOW figure for the Boers is around 4,000 – this implies the Boers were better soldiers – for every 1 Boer killed in combat 2 Brits are killed in combat (2:1 ratio) – this leads to the myths of the Boers been “better marksman” than the British or the Boers had better command and operational prowess – the British according to these myths were then “Lions led by Donkeys”.

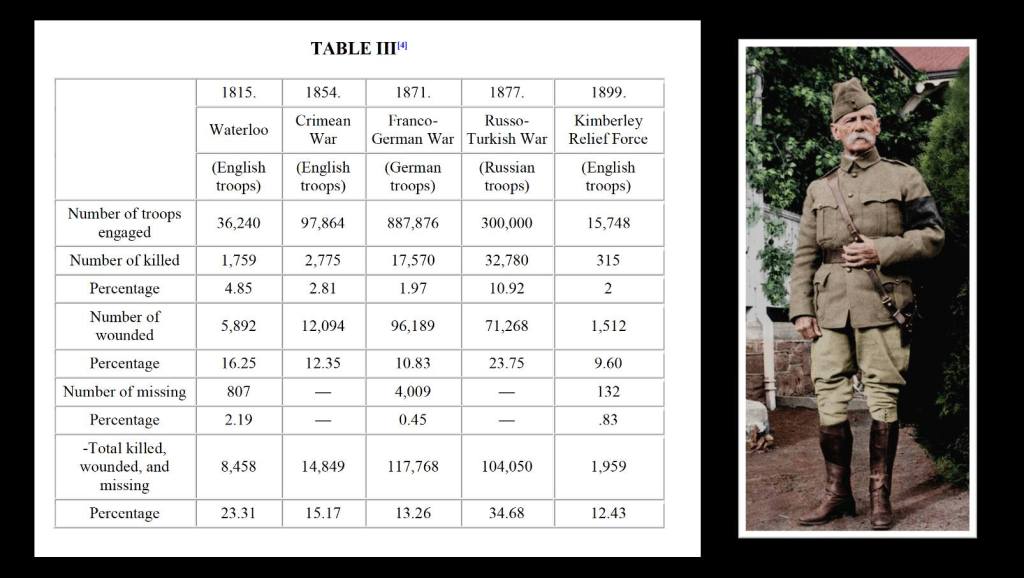

However truth be told is on the survivability given the respective troop size and different doctrine, if you were a British soldier in South Africa in a combat role, your chance of surviving combat without been KIA or DOW was 98% – there was a 2% chance a Boer bullet would kill you – which is pretty good survivability by British doctrine which was “Hidebound by Tradition” with costly frontal attacks and bayonet charges and antiquated cavalry and lancer charges.

If you were a Boer combatant, given your overall troop size and strength, you had a 93% chance of combat survival and a 7% chance of been KIA or DOW from a British bullet. Which is not very good given Boer doctrine actually focussed on high degrees of survivability, choosing to break engagements, reconcile and fight another day (mobility and manoeuvre) – rather than stand and be bayonetted, cleaved and then impaled from a costly British frontal assault of infantry, cavalry and lancers – none of which appealed to the Boer way of fighting and doctrine for mounted infantrymen.

Bottom line – on casualties – statistically speaking the British command in the Boer War actually was pretty good given the improvements over time in doctrine from Waterloo to the Crimean War (see chart above), the Boer command on controlling casualties and survivability on the other hand was much poorer. One thing the British are NOT are “bad shots” and their Commanders are certainly NOT “Donkeys”. Simply put, if you were British you had a better chance of surviving combat, the point where the metal is flying around, than if you were a Boer.

In Conclusion

Numbers speak more to truths than anything else, and the truth is the numbers support the idea that the Boers invaded the British colonies whilst they were numerically inferior and the Boers numerically superior, for the purposes of changing the regional balance between Boer and Brit and establishing a unitary state under “Afrikaner” influence – and not only does the republican planning and objectives point to this, their military strategy, doctrine and statements of intent supports it – and it is statistically proven.

The idea that the British were building up an invasion force on the borders is complete Hollywood and panders to the ‘politically inspired’ sabre waving in the “ultimatum” delivered by the Boers and not to the reality on the ground at all. The idea that the Boers invaded British colonies for the purposes of forward defences or as some sort of pre-emptive strike is also completely unsupported by what actually happens, the actual plans and this assertion is woefully unsupported by military doctrine – entirely debunked by the science of military history.

Also, the idea that the Boer command and doctrine is somehow better than that of the British is completely statistically unproven, in fact the opposite is true, the ‘numbers’ point in favour of the British – so too does an analysis of the three aspects of effective command – on the Strategic level, the Tactical level and the Operational level.

Written, researched by Peter Dickens

With thanks to Tinus Le Roux and Jenny Bosch for the use of colourised images.

Related Work

Boer War 3 – The Maritz Revolt Boer War 3 and beyond!

The Black Concentration Camps of the Boer War The ‘BLACK’ Concentration Camps of the Boer War

The intended Boer invasion of Rhodesia The planned Boer invasion of Rhodesia

The Jameson Raid ‘Hurry Up’ and prove it!

References:

“Rights and wrongs of the Transvaal war” by Edward t. Cook. Publication date 1901

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery “The Second Boer War – The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902” – Volumes 1 to 7.

Military History Journal, Vol 6 No 3 – June 1984. The Medical Aspect of the Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902 Part II by Professor J.C. de Villiers, MD FRCS.

The Anglo-Boer war: A chronology. By Cloete, Pieter G

The Battle of Magersfontein – Victory and Defeat on the South African Veld, 10-12 December 1899. Published 2023. By Dr. Garth Bennyworth.

Dr David Brock Katz; ‘General Jan Smuts and his First World War in Africa 1914 -1917’

Dr Evert Kleynhans and Dr David Brock Katz; ’20 Battles – searching for a South African Way of War 1913 – 2013’.

Anglo-Boer War Blockhouses – a Field Guide by Simon C. Green, fact checking and correspondence – 2023.

The Boer War: By Thomas Pakenham – re-published version, 1st October 1991.

Correspondence and interviews with Dr. Garth Bennyworth, Boer War historian – Sol Plaatjies University, Kimberley – 2023.

Interviews with Dr. David Broc Katz, University of Stellenbosch, South African Military Academy – Military historian – focus on Jan Smuts and fact checking Boer and British military doctrine – 2023.

Correspondence on fact checking British doctrine with Chris Ash, BSc FRGS FRHistS, Boer War historian, Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society for The Boer War Atlas – 2023.

History of the war in South Africa 1899-1902. By Maj. General Sir Frederick Maurice and staff. Volumes 1 to 4, published 1906

In 1876, King Khama, Chief of the Bamangwato people from northern Bechuanaland, joined the appeal:

In 1876, King Khama, Chief of the Bamangwato people from northern Bechuanaland, joined the appeal:

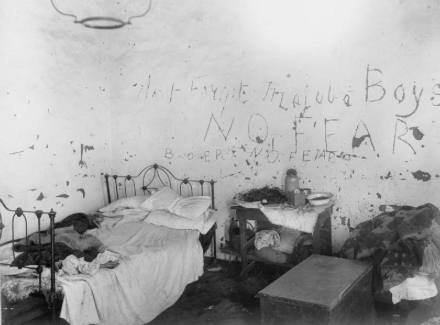

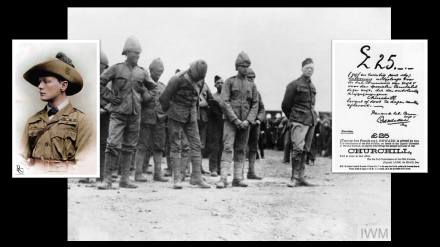

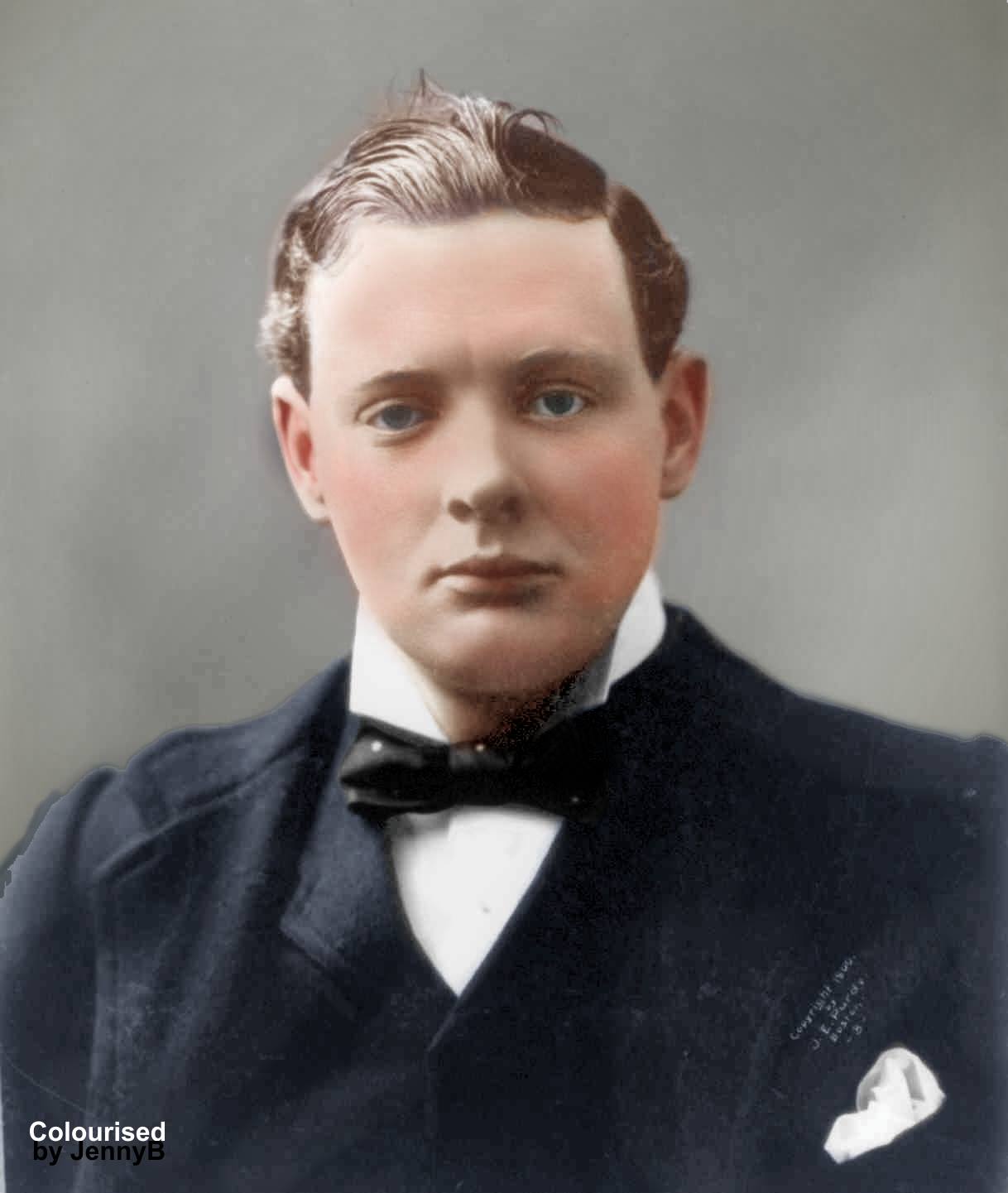

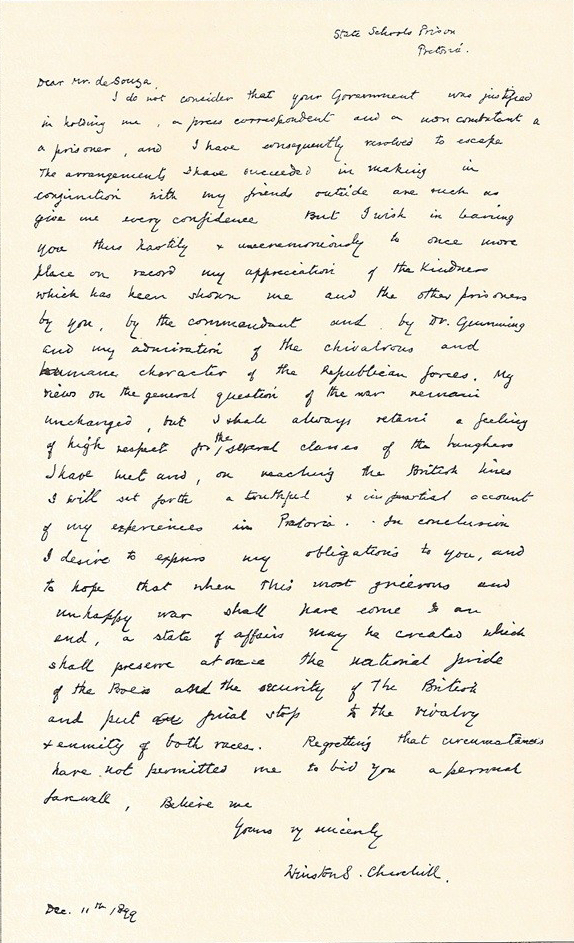

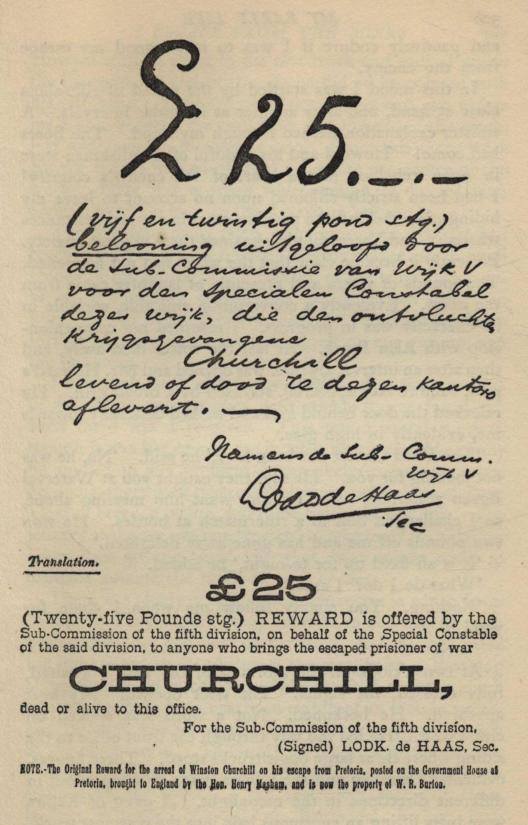

Because Churchill’s exploits in the South African War were marketed as a grand adventure, it vaulted this failing politician into the annuals of British heroism and resuscitated his career in a manner that can only be described as ‘stellar’.

Because Churchill’s exploits in the South African War were marketed as a grand adventure, it vaulted this failing politician into the annuals of British heroism and resuscitated his career in a manner that can only be described as ‘stellar’.

It a ‘myth’ that Britain had built up large forces to invade the Boer Republics before the start of the war. The ‘truth’ is they were relatively unprepared and much weaker than the well equipped Boer forces – ‘Black November’ illustrates this perfectly. The Boers had banked on a swift victory whilst Britain was weak, hence their ultimatum was followed immediately with a surprise Boer invasion of the British colonies – Natal and the Cape Colony.

It a ‘myth’ that Britain had built up large forces to invade the Boer Republics before the start of the war. The ‘truth’ is they were relatively unprepared and much weaker than the well equipped Boer forces – ‘Black November’ illustrates this perfectly. The Boers had banked on a swift victory whilst Britain was weak, hence their ultimatum was followed immediately with a surprise Boer invasion of the British colonies – Natal and the Cape Colony.

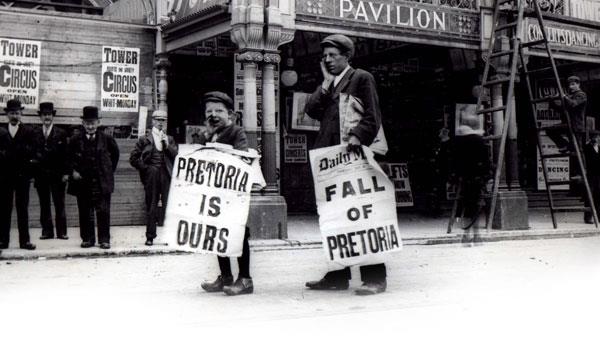

After the victory in Pretoria, Winston returned to Cape Town and sailed for Britain in July 1900, on the very same ship he had arrived on, the Dunottar Castle. While he had still been in South Africa, his Morning Post despatches had been published as London to Ladysmith via Pretoria, and they sold like wildfire. He arrived a national hero, nearly god-like, adored by millions.

After the victory in Pretoria, Winston returned to Cape Town and sailed for Britain in July 1900, on the very same ship he had arrived on, the Dunottar Castle. While he had still been in South Africa, his Morning Post despatches had been published as London to Ladysmith via Pretoria, and they sold like wildfire. He arrived a national hero, nearly god-like, adored by millions.