This featured informal ‘happy snap’ of Magnus Malan, PW Botha and Jonas Savimbi on the Angolan border speaks volumes – it most certainly highlights the political edict “the enemy of enemy is my friend” and carries with it the typical sort of politics which involves ‘odd bedfellows’; the kind of story which involves intrigue, betrayal and political assassination.

South Africa’s relationship with Savimbi and UNITA the ‘National Union for the Total Independence of Angola’ was indeed an odd pairing, it started with UNITA as an ‘enemy’ of the South African Defence Force in their commitments to help Portugal in the Angolan War. Once Portugal left Angola, an ‘ally’ was made of UNITA when it was in South Africa’s interests in destabilising Angola to stop SWAPO (PLAN) armed insurgencies entering into South West Africa (now Namibia) from Angola. The ‘alliance’ was made stronger when ramped up Cuban military presence entered the frame in the Angolan conflict, and UNITA was made a pawn in South Africa’s ‘total war’ against communist expansionism in Southern Africa. In the ultimate betrayal South Africa then hung UNITA out to dry when Cuban troops left Angola.

It really is a case of South Africa ‘shooting at UNITA’ which changed to a case of ‘shooting alongside UNITA’ and then became a case of ‘shooting UNITA dead’.

To be fair, the United States of America was also as compliant in the betrayal. So how did it all begin?

Shooting at UNITA

In the 1960s, during the armed struggle against Portuguese colonial rule, Savimbi founded UNITA, and along with the two other ‘anti-colonial liberation movements’ – the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) and the ‘Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola’ (MPLA) – they all started to fight Portugal for an independent Angola. UNITA and the FNLA were also against MPLA rule but that inconvenient difference was put aside to fight Portugal. Aggression between the MPLA and UNITA started in earnest again when the Portuguese ultimately left and a power vacuum ensued.

- MPLA

- FNLA

- UNITA

UNITA carried out its first attack against Portuguese forces on 25 December 1966 by derailing railways. At that time, beleaguered by three anti-colonial movements Portugal turned to South Africa and Rhodesia for military help. Both South African and Rhodesia governments were concerned about their own future in the case of a Portuguese defeat in neighbouring Angola and Mozambique.

Rhodesia and South Africa initially limited their participation to shipments of arms and supplies. However, by 1968 the South Africans began providing Alouette III helicopters with crews to the Portuguese Air Force (FAP), and finally there were reports of several companies of South African Defence Force (SADF) infantry who were deployed in southern and central Angola (primarily to defend iron mines in Cassinga).

SAAF Puma in support of Portuguese troops in Angola

When the first Portuguese unit was equipped with South African Air Force Puma helicopters in 1969, the crews were almost exclusively South African. In all the SADF had pilots and helicopters operating out of the Centro Conjunto de Apoio Aéreo (CCAA – Joint Air Support Centre) in support of Portuguese military actions against the MPLA and UNITA alike. The SADF set up its joint operations in Cuito Cuanavale during 1968. In an iconic sense the small town of Cuito Cuanavale in the South East of Angola was to be the beginning the South African military involvement in Angola and almost exactly two decades later this small town would signal the end of South African involvement in Angola – having now come full circle.

So far in the war, none of the three nationalist groups (UNITA, MPLA and FNLA) had posed a serious threat to Portuguese rule in Angola. But in 1974, a Left-wing coup in Portugal brought to power a regime which pledged to end all wars in the country’s African colonies – Angola, Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau – and to introduce democracy at home. This seismic change in Portuguese politics and foreign rule became known as the ‘Carnation Revolution’.

Shooting alongside UNITA

By the time the Portuguese military (and its South African help) left Angola in 1975, the country was in political chaos. Savimbi was soon leading the fight against the future government of President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, leader of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA).

In July 1975, the Soviet Union and Cuban Communist backed MPLA forces attacked and swept UNITA and FNLA forces out of the capital, Luanda. This resulted in a international refugee crisis, made worse by thousands of Portuguese nationals streaming into South African territories in fear of their lives. The United States of America (USA) then entered the fray by supplying arms to both UNITA and the FNLA to hold back this onslaught of Communist backed guerrillas in the MPLA. The USA saw UNITA as an ally in the fight against Communist domination in Africa, the Americans also turned to South Africa for help, South Africa also held a fierce anti-Communist stance and was taking the brunt of Portuguese refugees fleeing Angola.

South Africa’s fight by this time had also turned to the South West African Peoples Organisation (SWAPO), who had commenced an armed insurrection campaign for South West African (Namibian) independence – at the time a South African protectorate bordering Angola, SWAPO began using bases in Angola and was been supported by the MPLA.

With both the Soviet Union and the USA arming major factions in the Angolan Civil War, the conflict escalated into a major Cold War battleground. Coming the assistance of the Americans was South Africa, in many ways positioning itself as a ‘Ally’ of the NATO western states in their Cold War with Communism, as it had been in WW2. Conversely it also aided the South African government’s need to soften the ‘West’s’ stance on the National Party’s policies of Apartheid.

By August 1975 BJ Vorster, the South African Prime Minister, along with his Defence Minister PW Botha, struck an extraordinary deal. Vorster authorised the provision of limited military training, advice and logistical assistance to UNITA and the FNLA. In turn FNLA and UNITA would help the South Africans fight SWAPO. The ‘enemy of his enemy – became his friend’.

This kicked off Operation “Sausage II”, a major raid against SWAPO in southern Angola and on 4 September 1975. This was immediately followed by Operation Savannah and then by many more large scale armed incursions and small scale raids into Angola in support of UNITA and against SWAPO bases in Angola – from 1975 all the way to 1989. SADF South African soldiers literally found themselves fighting ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with UNITA Angolan soldiers for the next 14 years. Jonus Savimbi himself was even given the code-name ‘Spyker’ (Spike) by the SADF members working with UNITA.

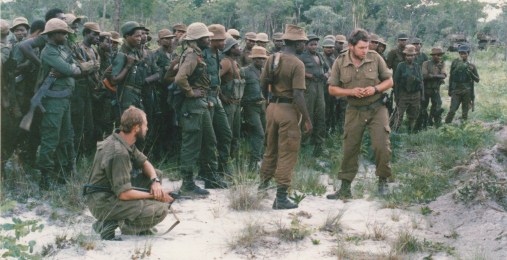

SADF Troops and UNITA troops in Angola

The ‘Odd Couple’ Alliance

Thus began a two decade long Alliance with UNITA in a proxy Cold War fight against International Communism, and strange bedfellow alliance between an anti-colonial freedom movement and ‘Apartheid’ South Africa.

With continuing aid from South Africa, Savimbi was able to fight on. By 1977, UNITA was becoming a powerful threat to the Luanda government, carrying out operations without apparent difficulty.

In the early 1980s, Savimbi further increased his power. South African “hot pursuit” attacks against SWAPO rebels in southern Angola forced the Luanda government to concentrate its forces in that part of the country, leaving Unita a free hand to consolidate bases throughout the rest of Angola.

Yet, although strengthened by heavy Soviet weapons captured by South African troops and American weapons, Savimbi was well aware that he could never take Luanda against the combined Cuban and MPLA government armies with Soviet support. He based his hopes on forcing the MPLA to agree to a coalition government and to free elections.

UNITA, SADF and National Party members

However, by 1986 he was under intense pressure from Luanda’s combined forces, which had seized large areas of his territory. Pretoria had informed Washington that UNITA would need more arms to meet continued attacks, and Savimbi decided to go to America to appeal for help in person.

In Washington, he succeeded in putting his case to President Reagan; and Congress proposed a programme of covert aid which enabled the first American Stinger anti-aircraft missiles to reach UNITA within a few months.

Savimbi continued to enjoy military successes, however by the late 80’s the Soviet Union had commenced political reform, Cuban involvement in Angola had met with repeated defeats, limited success, high loss of life and an economic and military drain, and domestically South Africa was preparing for domestic political reform against growing international pressure and sanctions against Apartheid.

It all came to a head with a military stalemate at Cuito Cuanavale in 1988 (where it had all oddly started in the mid 1960’s). South Africa intervened to block a large-scale MPLA attack with Soviet and Cuban assistance against UNITA’s primary operating bases at Jamba and Mavinga. The campaign culminated in the largest battle on African soil since World War 2 and the second largest clash of African armed forces in history. The MPLA offensive was halted and a stalemate ensued.

The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale is credited with ushering in the first round of trilateral negotiations mediated by the USA. The Tripartite Accord involved Angola’s MPLA government, South Africa and Cuba (without UNITA). While the hostilities in Angola continued at Cuito Cuanavale, negotiations initially reached a deadlock.

It was broken by the South African negotiator, Pik Botha, who convinced the delegates that “…We can both be losers and we can both be winners…” Pik Botha offered a compromise that would appear to be palatable to both sides while emphasising that the alternative would be detrimental to both sides.

His proposal, South Africa could claim ‘Victory’ with the removal of Communist military aggression from Southern Africa (including Angola), and Cuba could claim ‘Victory’ with the withdrawal of South Africa from Namibia (South West Africa) in accordance with United Nations Resolution 435 (tabled 10 years earlier in Sep. 1978).

The middle-ground was struck on that simple premise and was to be known as the Tripartite Accord, Three Powers Accord or New York Accords, South Africa, Angola (MPLA government) and Cuba all signed the bottom line on 22 December 1988.

Shooting UNITA dead

Savimbi refused to accept the Tripartite Accord, which also forbade further military aid being supplied to any rebel groups – which included UNITA in the definition of ‘rebel group’; then, in January 1989, President Bush (Snr) reassured Savimbi that American arms would continue to be sent to UNITA for as long as Cuban forces remained in Angola.

With a phased timetable for the withdrawal of Cuban forces to be completed by June 1991, Savimbi was ready to fight on. Almost immediately in the beginning of 1989 Angola accused South Africa of breaking the agreement by supplying arms to Savimbi.

Pretoria denied aiding UNITA. Savimbi then approached the South African government to size up the situation with an ailing and politically beleaguered President P.W. Botha, who told him very bluntly that all South African aid to UNITA was to be cut off.

In plain language, UNITA was no longer South Africa’s ‘friend’. Jonas Savimbi was for 20 years, a figure as important in Southern African politics as Nelson Mandela, and he was now officially out in the cold, UNITA had become an embarrassment and hindrance to the seismic global geo-politics between the Soviet Union, Cuba, Namibia, Angola, South Africa and the United States of America in 1989.

The ceasefire between South Africa and Cuba/MPLA Angola and the path to independence for Namibia had been the last acts of PW Botha’s legacy as President, later in 1989 (August 14th), F.W. De Klerk took control of Presidency due primarily to P.W. Botha’s failing health.

Betrayal

If the American betrayal of Savimbi was not bad enough, this last dismissal by PW Botha was the final betrayal of UNITA, it was the ‘nail in the coffin’; with the loss of South Africa as an ally (in addition to the USA), UNITA literally stood no hope at all. Jonus Savimbi’s fate was sealed, along with that of UNITA.

Savimbi’s international isolation was further increased when, after a peace deal had been struck and elections held in 1992 in Angola, he refused to accept either his defeat at the polls or a role in a power-sharing government. He withdrew to Huambo in his country’s central highlands, and from there he fought on.

Savimbi’s international isolation was further increased when, after a peace deal had been struck and elections held in 1992 in Angola, he refused to accept either his defeat at the polls or a role in a power-sharing government. He withdrew to Huambo in his country’s central highlands, and from there he fought on.

UNITA continued to fight on unsupplied and rather vainly on their own till 2002, until Jonus Savimbi was finally shot dead on the 22nd February by advancing MPLA troops.

Jonus Savimbi was a highly educated and charismatic leader. A burly man, 6ft tall and with a bearded face that could as easily convey an expression of menace as break into a dazzling smile, Jonas Savimbi was usually photographed wearing well-pressed camouflage fatigues and a jaunty beret. At his hip there was often a pearl-handled revolver; and he had a favourite ivory-topped cane.

Jonus Savimbi once gave PW Botha an AK47 assault rifle made out of ivory as a gift of friendship, a gift that remained on display at the George Museum in South Africa for some years until 1998 (when all of PW Botha’s gifted artefacts were removed).

The ivory AK-47 now stands as an unusual reminder of how history can be unkind and the absurdity of getting into bed with ‘strange political bedfellows’. It really is a symbol of the type of betrayal which so often comes with the political edict; “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”.

Researched by Peter Dickens. Source – various obituaries, including the Daily Telegraph of Jonus Savimbi and Wikipedia