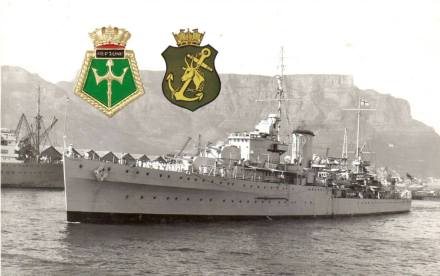

This image of HMS Neptune with Table Mountain in the background says a lot about the South African naval personnel seconded to serve on Royal Navy vessels and their supreme sacrifice.

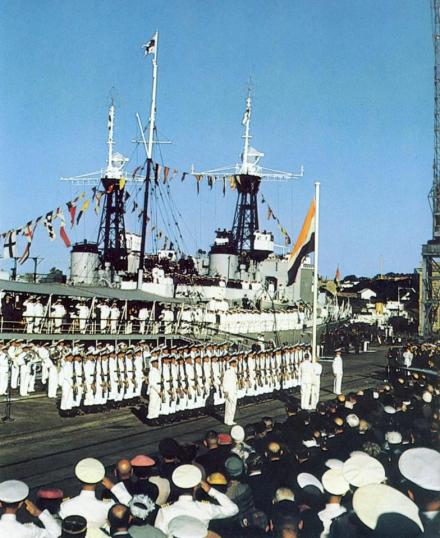

As Simonstown was a British naval base during the Second World War thousands of naval ratings and officers who volunteered to serve in the South African Navy – known as the South African Navy Forces – landed up on British vessels. So when one was sunk, as HMS Neptune was, inevitably there is a very long honour roll of South Africans. Read on for their story.

HMS Neptune was a Leander-class light cruiser commissioned into the Royal Navy on 12 February 1934 with the pennant number “20”.

HMS Neptune at sea in her heyday.

Force K, operating in the Mediterranean, including HMS Neptune, was sent out on 18 December 1941, to intercept an Axis forces convoy (German and Italian) bound for Tripoli,

On the night of 19 – 20 December, HMS Neptune, leading the line, struck two mines, part of a newly laid Italian minefield. The first struck the anti-mine screen, causing no damage. The second struck the bow hull. The other cruisers present, HMS Aurora and HMS Penelope, also struck mines.

On the night of 19 – 20 December, HMS Neptune, leading the line, struck two mines, part of a newly laid Italian minefield. The first struck the anti-mine screen, causing no damage. The second struck the bow hull. The other cruisers present, HMS Aurora and HMS Penelope, also struck mines.

While reversing out of the minefield, Neptune struck a third mine, which took off her propellers and left her dead in the water. HMS Aurora was unable to render assistance as she was already down to 10 knots (19 km/h) and needed to turn back to Malta. HMS Penelope was also unable to assist.

The destroyers HMS Kandahar and HMS Lively were sent into the minefield to attempt a tow. The former struck a mine and began drifting. Neptune then signalled for Lively to keep clear. (Kandahar was later evacuated and torpedoed by the destroyer Jaguar, to prevent her capture.)

Neptune hit a fourth mine and quickly capsized, killing 737 crew members. The other 30 initially survived the sinking but they too died. As a result, only one was still alive when their carley float was picked up five days later by the Italian torpedo boat Achille Papa.

The loss of HMS Neptune was the second most substantial loss of life suffered by the Royal Navy in the whole of the Mediterranean campaign, and ranks among the heaviest crew losses experienced in any naval theatre of World War II.

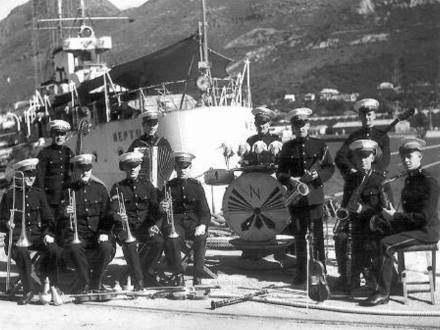

The Royal Marine band on the jetty by the stern of HMS Neptune at Simon’s Town in July 1940

This is the honour roll of South Africans lost that day lest we forget the heroism and sacrifice of these brave South African men.

ADAMS, Thomas A, Able Seaman, 67953 (SANF), MPK

ADAMS, Thomas A, Able Seaman, 67953 (SANF), MPK

CALDER, Frank T, Ordinary Seaman, 67971 (SANF), MPK

CAMPBELL, Roy M, Able Seaman, 67318 (SANF), MPK

DIXON, Serfas, Able Seaman, 67743 (SANF), MPK

FEW, Jim, Able Seaman, 67744 (SANF), MPK

HAINES, Eric G, Able Seaman, 67697 (SANF), MPK

HOOK, Aubrey C, Able Seaman, 67862 (SANF), MPK

HOWARD, Harold D, Signalman, 67289 (SANF), MPK

HUBBARD, Wallace S, Able Seaman, 67960 (SANF), MPK

KEMACK, Brian N, Signalman, 67883 (SANF), MPK

MERRYWEATHER, John, Able Seaman, 67952 (SANF), MPK

MEYRICK, Walter, Ordinary Signalman, 68155 (SANF), MPK

MORRIS, Rodney, Ordinary Signalman, 68596 (SANF), MPK

RANKIN, Cecil R, Signalman, 67879 (SANF), MPK

THORP, Edward C, Signalman, 67852 (SANF), MPK

THORPE, Francis D, Able Seaman, 67462 (SANF), MPK

WILD, Ernest A, Able Seaman, 67929 (SANF), MPK

Other South Africans who had enlisted into the Royal Navy were also lost, these include (and by no means is this list definitive) the following:

OOSTERBERG, Leslie W, Stoker 1c, D/KX 96383, MPK

TOWNSEND, Henry C, Stoker 1c, D/KX 95146, MPK

May they Rest in Peace, these brave men whose duty is now done.

HMS Neptune in Cape Town harbour

Researched by Peter Dickens, Sources – Wikipedia. Casualty Lists of the Royal Navy and Dominion Navies, World War 2 by Don Kindell

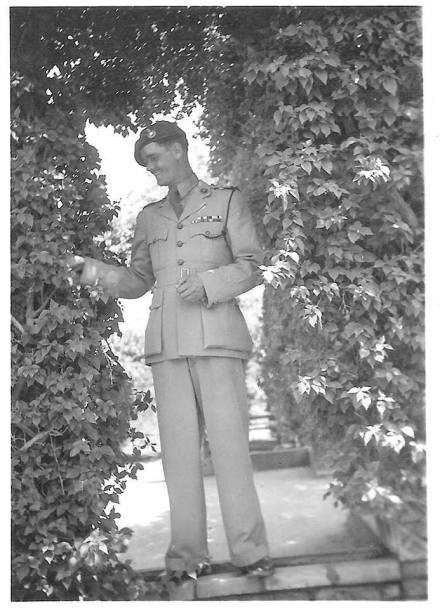

His most painful recollection of D-Day was the stormy passage he and his contingent had to undergo in crossing the Channel in their landing craft.The seas were running high, and hardly a man escaped sea sickness. They landed in the second wave at first light, their boat receiving a direct hit as they approached the shore, half-a-dozen men being killed, and Thomas found himself up to his neck in water after having jumped form the landing craft as it struck the beach.

His most painful recollection of D-Day was the stormy passage he and his contingent had to undergo in crossing the Channel in their landing craft.The seas were running high, and hardly a man escaped sea sickness. They landed in the second wave at first light, their boat receiving a direct hit as they approached the shore, half-a-dozen men being killed, and Thomas found himself up to his neck in water after having jumped form the landing craft as it struck the beach.

Lt Thomas won the Military Cross (MC) for his actions in World War 2. A significant decoration, it is awarded for gallantry in combat. The MC is granted in recognition of “an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land to all members, of any rank in Our Armed Forces”.

Lt Thomas won the Military Cross (MC) for his actions in World War 2. A significant decoration, it is awarded for gallantry in combat. The MC is granted in recognition of “an act or acts of exemplary gallantry during active operations against the enemy on land to all members, of any rank in Our Armed Forces”.

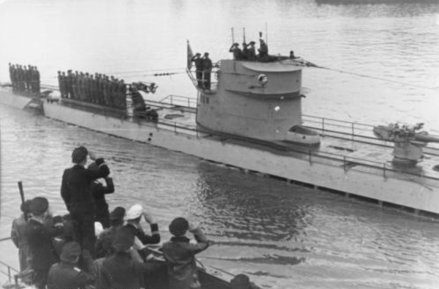

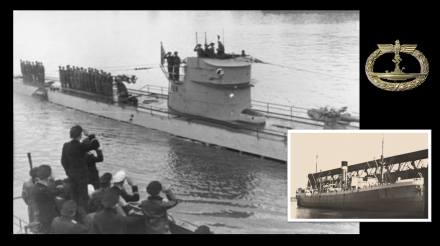

A typical example of the danger, survival and sacrifice in South African waters is the story of the sinking of the “City of Johannesburg” by German submarine U-504 (seen in the featured image above). U-504 was a Type IXC U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II, the SS City of Johannesburg was a merchant vessel carrying supplies off the coast of East London, South Africa.

A typical example of the danger, survival and sacrifice in South African waters is the story of the sinking of the “City of Johannesburg” by German submarine U-504 (seen in the featured image above). U-504 was a Type IXC U-boat of Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine during World War II, the SS City of Johannesburg was a merchant vessel carrying supplies off the coast of East London, South Africa.