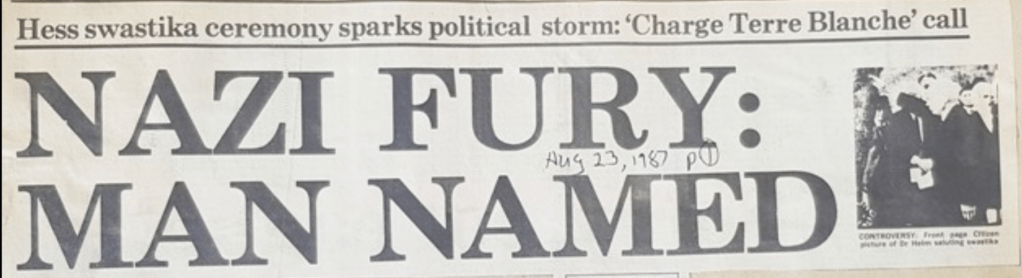

I am currently doing some research into Radio Zeesen, the Nazi German foreign service radio station broadcasting worldwide (much the way BBC world service still broadcasts today), and this image cropped up, now imagine – its 20 August 1987, 40 years after the end of World War 2 and in full view of the Nazi holocaust, and here’s Dr. Erich Holm and his supporters happily giving Nazi salutes and draping Nazi flags over a German war memorial, located rather surprisingly, in a cemetery in central Pretoria, South Africa.

Naturally it kicked up a fuss at the time – after all, it’s 1987 – the formal honouring of Nazi Flags and Nazi leaders in a country scarred by the war against Nazism is simply outrageous and insulting to the majority of modern South Africans – especially those whose forebears were lost or who took part in World War 2 or those military veterans who are still alive, most aged around 60 years old then. Not to mention the vast majority of South Africans who see this symbology in light of racial subjugation – rather unsurprisingly in the middle of all of this furore is the leader of the Afrikaner Resistance Movement (Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging) – the AWB .. now what’s going on?

So, here’s a little background to this scandal. During World War 2 (1939-1945), Hitler’s propaganda Minister engaged Radio Zeesen for all outbound broadcasting of Nazi propaganda, a specific market for this was identified in South Africa in the form of far right Afrikaner radicals – a variety of political parties and cultural organs – mainly the ‘Reformed’ or ‘Pure’ National Party, the Ossewabrandwag, the New Order, the Grey Shirts, the Black Shirts, the Boerenasie Party – the list goes on.

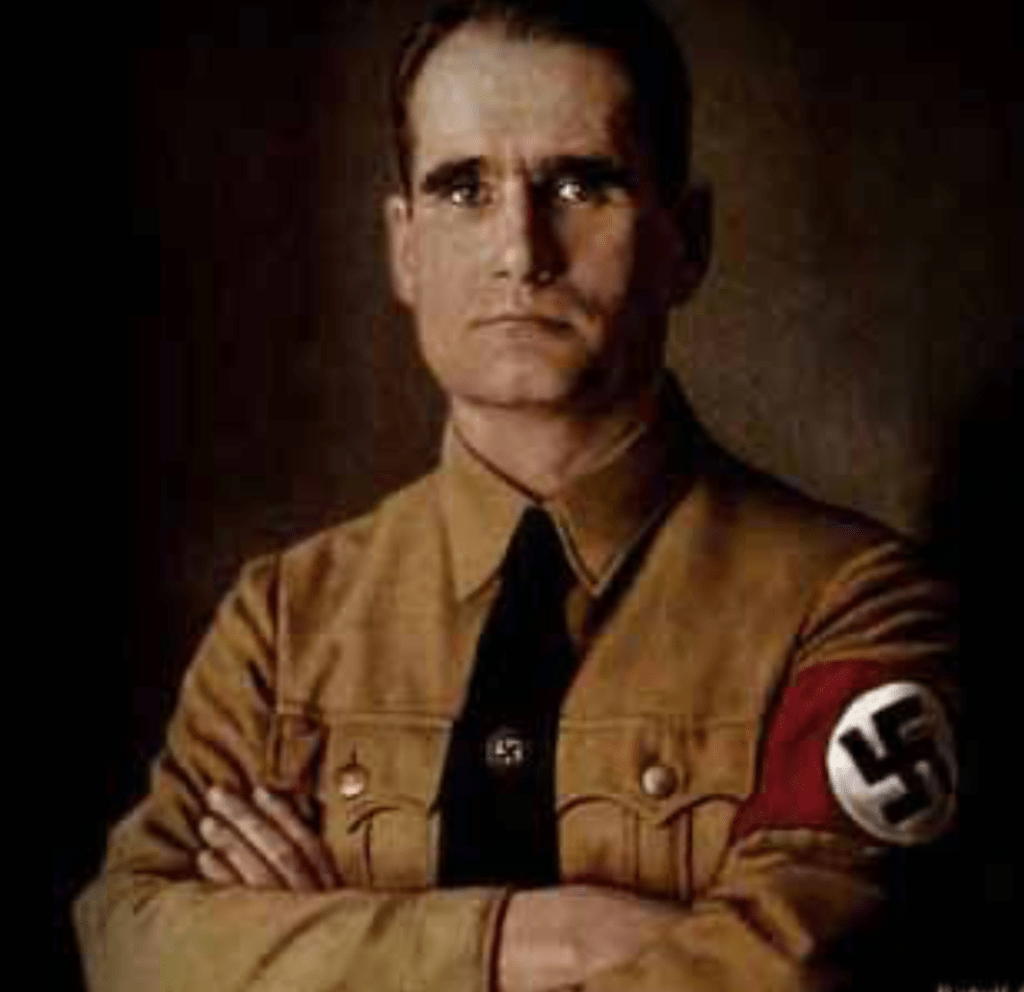

Three South African nationals were in Germany at the time World War 2 kicked off – Dr. Sidney Erich Holm, Dr. Jan Adriaan Strauss and Johannes Jacobus Snoek were recruited by the German Propaganda Ministry to run their ‘Afrikaans’ service on Radio Zeesen – which broadcasted worldwide in a variety of languages on short-wave transmissions. The positioning taken by Radio Zeesen with regard South Africa was a suggested National Socialism (Nazi) alliance with Afrikaner Nationalism, it also focussed on subverting the Smuts government and disseminated general anti-British sentiment in South Africa – it used talk, news and cultural programs to forward these aims – using these three Afrikaner broadcasters – all using the alias “Neef” meaning “cousin”, the main Afrikaner broadcaster was Erich Holm – his alias was Neef Holm.1

After the war ended in 1945, Holm, Straus, Pienaar and Snoek were all arrested for high treason on the basis of conducting subversive activities against the Union of South Africa during war-time, voluntarily working with Nazi Germany in forwarding their objectives and endangering South African lives. They were all prosecuted in South Africa, to ‘beat the rope’ or avoid lengthy jail terms their defence revolved around being mere employees of the German state radio service – they did not commit any “hostile intent” against South Africa – the argument used was a common one used in cases like this in South Africa at the time – that there is a difference between a ‘Land Veraaier’ (traitor to your country) and a ‘Volk Veraaier’ (traitor to your people) – they were merely warning South Africans and in their estimation they were still South African patriots – only they had a different view, that’s all.

Regardless of this rather convoluted sense of what constitutes treason, they were all however found guilty of high treason on the legal precedents thereof. Dr. Erich Holm is given a ten year sentence. Fortuitously for all of them, when the National Party walked into power in 1948, one of their first acts was to grant full amnesty to all South Africans convicted of war-time treason – so they all walked out their prosecutions free men, Dr. Holm having served three years of his sentence.2

Farewell Herr Hess

Now, spool on 40 years or so, Rudolf Hess, the only surviving member of Hitler’s inner circle has been sitting in Spandau prison in Germany on a life sentence for crimes against humanity – for all this time on a sentence that really meant ‘Life’. He’s now 93 years old and despite years of campaigning by a small group for release on compassionate grounds of old age, Hess continued to be an unapologetic Nazi and a devout antisemite. On 17 August 1987 he is found dead hanging in the prison grounds from a chord, having committed suicide (some contested that on the basis of his frailty in age).

Saddened by the loss of his old Nazi hero, enter stage left our old South African Radio Zeesen broadcaster, Dr. Erich Holm, emboldened by his National Party amnesty he truly nails his Swastika to the mast – literally. In conduction with some like-minded Nazi German friends who had found South Africa a welcoming home under the Afrikaner Nationalists and some members of Eugène Terre’Blanche’s Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB), Holm decided to arrange a suitable ‘auf Wiedersehen’ (farewell) for Rudolph Hess.

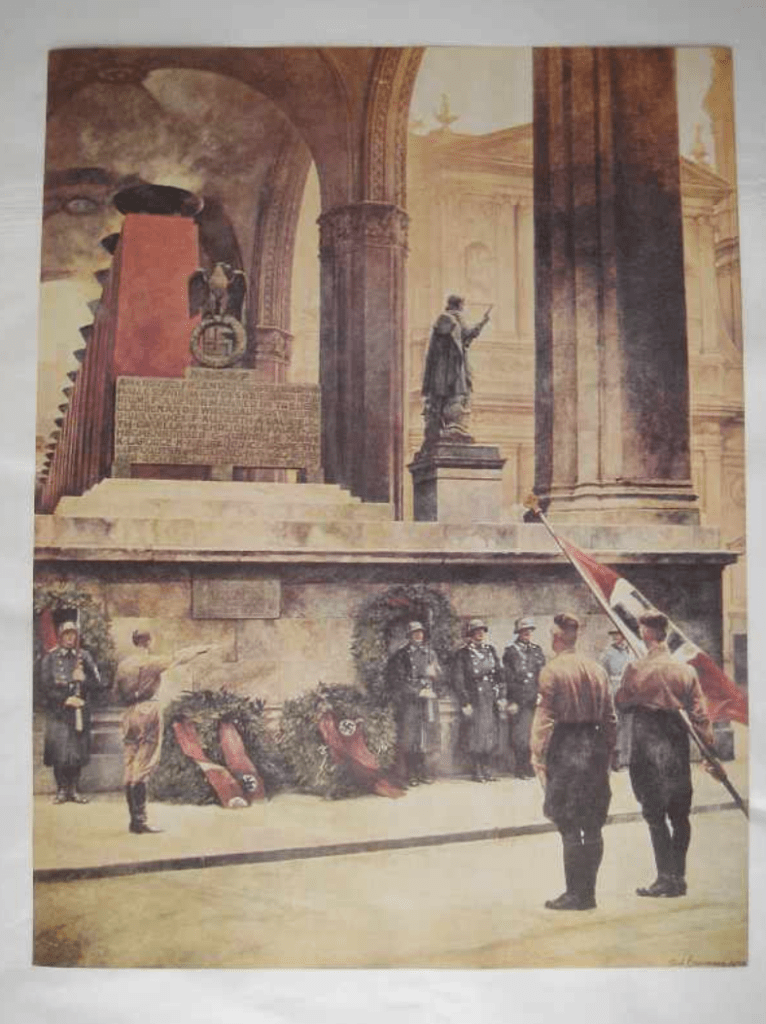

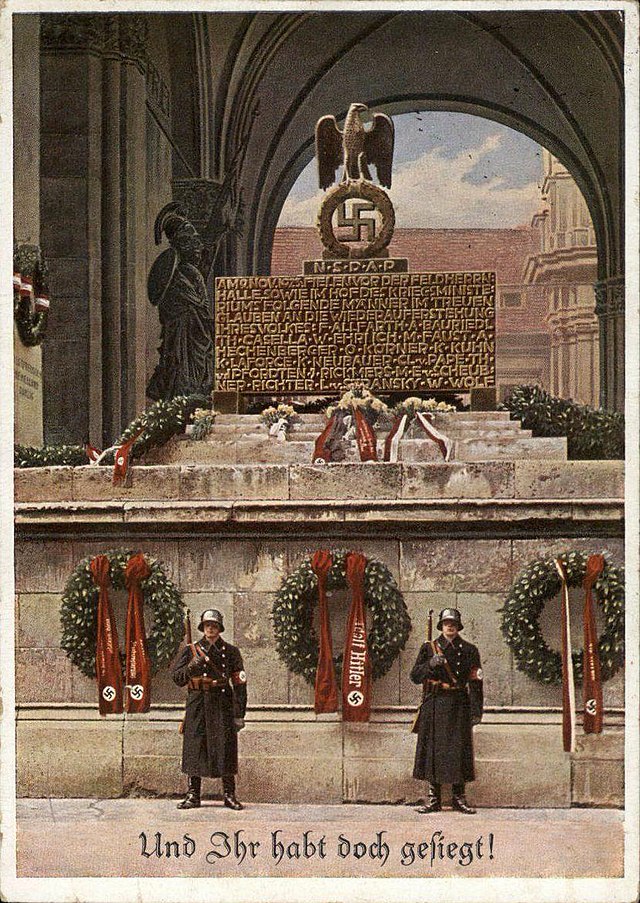

Their Memorial Service for Rudolf Hess is held at a German War Memorial in Pretoria, its a cenotaph to the German Fallen of both war – World War 1: 1914-1918 (written on one side) and World War 2: 1939-1945 (written on the other side), complete with metal wreath and eternal flame with accompanying dish. The cenotaph is strangely enough located in the middle the Pretoria West Cemetery – also known as New Cemetery, Newclare Cemetery, Pretoria West Cemetery – address: 322 Rebecca St, Philip Nel Park, Pretoria. It’s still there.3

How a German War Cenotaph finds its way into a Pretoria cemetery is anyone’s guess – it is unusual to find German war cenotaphs in countries who fought against Germany in both the wars commemorated. In any event, on 20 August 1987 (three days after Rudolf Hess passes), in full public view, Dr Eric Holm and his pals light the flame of remembrance, drape the cenotaph in gigantic red, white and black Nazi Swastika flag, hold a service to Rudolf Hess, salute the Cenotaph (and by that way Rudolf Hess) using the Nazi styled strait armed ‘Heil Hitler’ salute and play Nazi German period music over a Public Address system.

The media get wind of this Memorial Service to Rudolf Hess but are uninvited and in fact warned to stay away, a reporter from The Citizen and photo journalist – Neville Petersen are sent out to the memorial service, Petersen climbs over the fence while the reporter stays in the car. He hides behind a large headstone far enough away so as not be seen but close enough to take a photograph. Which he does of one the elderly Nazi attendees saluting Rudolf Hess, the memorial and the Nazi flag – once taken he’s back over the fence and into his awaiting get away car.4

Unrepentant

The published photo resulted in a media frenzy, driven by investigative journalists of the Sunday Times with the matter later landing up in Parliament, opposition MP’s demanding heads. The journalists, De Wet Potgieter and Jannie Lazarus identified Dr. Erich Holm at the centre of the controversy and interviewed him. What he said to them says just about everything:

Dr. Holm put forward that Rudolf Hess was a man of “peace” (somewhat mentally unhinged Hess parachuted into Britain on 10 May 1941 in the hopes of negotiating surrender terms for a Germany) and “never touched a hair on the head of any Jew (as) it would have been beneath him” .. Holm then accuses the Jews and says “its the jews who have refused to declare peace since the end of the war”.5

So for Erich Holm, the entire Holocaust should just be something the Jews should get over and move on, notwithstanding the fact it’s still in living memory of many Nazi Holocaust survivors in 1987, including many in South Africa

Holm bitterly recalled that the imprisonment of Hess was because “the Jews and the British were afraid of him” and that he “was locked up in an inhuman way” because of it.

On a personal level he once again suggested complete innocence for his role in Radio Zeesen’s Nazi propaganda stating he was never a member of the Nazi Party and merely as “a South African (who) broadcasted news, music and entertainment to South Africa”. 6

As a sort of fun throwaway, interest fact, Dr. Erich Holm said that Hitler was in favour of the white Afrikaner nation and a keen admirer of the Guerrilla tactics used by the Boer Republican forces during the South African War (1899-1902) and said:

“In fact Hitler told me personally of his admiration for the way the Boer Generals had fought the British, and singled out General Christiaan de Wet for special mention.” 7

Once again reinforcing his old Radio Zeesen propaganda brief without even giving it a thought, inadvertently and unwittingly linking Afrikaner Nationalism and Boer War “folks-helde” (people’s heroes) to National Socialism and Nazi Germany’s admiration for the white Afrikaner people. Something his defence team in his treason trial tried very hard to prove he did not do. The hard reality – the Leopard never really changed his spots. For more on Hitler and the Boer War follow this link: Hitler’s Boer War

What becomes increasingly clear from Dr. Holm’s comments is there is a fundamental disconnect in how he views Nazism and what Nazism was proven to ultimately be, an almost sociopathic distancing from really understanding and emotionally assimilating the genocide, trauma, death and hurt caused by National Socialism – something in which he was an active and willing participant, and something in hindsight he should have regretted.

Legacy

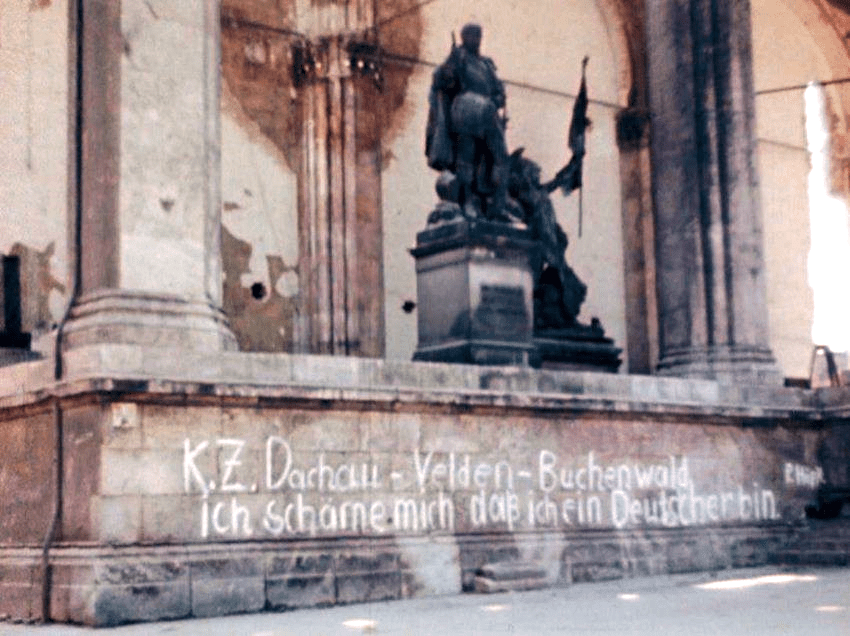

On celebrating Nazism and here’s the critical difference to how hero worship of Nazi elite was treated in Europe and the Soviet Union/Russia in the 1980’s and 1990’s – as opposed to how it was treated in South Africa.

In Germany, and even in death Rudolph Hess continued to be controversial, unlike his Hitler inner circle colleagues who shot themselves, were shot or hung and were buried in unmarked and unallocated graves or whose mortal remains are untraced to his day, Hess had asked that he be buried with his parents in the Wunsiedel cemetery and his wishes were complied with – making his grave the only real physical connection to formative Nazi leader.

Problem was – as the only real grave marker to a Nazi leader from the inner circle, each year on the anniversary of his death, neo-Nazis far right extremists from all over the world attempted to stage a march to the cemetery and salute the grave and gravestone epitaph “Ich hab’s gewagt” (“I have dared”). This despite court rulings banning it, causing the town to be shut-down with heavy police presence. It became such a menace, that when the graves lease expired 2001, the Hess’ remains were removed and cremated, the headstone removed and destroyed, and Hess’ ashes were scattered at sea by his surviving family.8 A move which was welcomed by the good people of Wunsiedel and just about every civic association and the Jewish German community. Even Spandau prison was demolished entirely to prevent it becoming a Neo-Nazi shrine.

In Afrikaner Nationalist South Africa however, no such police action was afforded to prevent such commemorations and open admiration of Nazism. The Afrikaner Resistance Movements (AWB) continued well into the 1990’s to openly fly Nazi Swastika flags alongside their very similar flags with impunity. Other organisations as well, investigative journalists found their way into commemorations of Hitler’s birthday at the time held by organisations like Koos Vermeulen’s World Apartheid Movement (WAB) and World Preservatist Movement (WPB).

Unlike in Germany, Russia and all over Europe, up until 1994, there is something that can most certainly be derived from the tacit approval and lack of real action by the Apartheid state to readily stamp out the use of Nazi symbology, emblems and hero worship. Also, unlike in Germany and Europe, where active steps were taken by the state to educate and expose the entire population to the evils of Nazism by way of sensitivity training, there is also something that can be said of no such steps having ever been really taken place in South Africa by the Apartheid state – and that is evidenced by the sheer arrogance and lack of understanding demonstrated by likes of the Dr Erich Holm.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

Related work:

Hitler’s South African Spies Hitler’s Spies and the Ossewabrandwag

The Nazification of the Afrikaner right The Nazification of the Afrikaner Right

References:

“Hitler’s Spies: Secret Agents and the Intelligence War in South Africa 1939-1945” by Evert Kleynhans – Jonathan Ball Publishers 2021.

F.L. Monama, Wartime propaganda in the Union of South Africa, 1939-1945 (PhD thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2014).

C. Marx, ‘“Dear Listeners in South Africa”: German Propaganda Broadcasts to South Africa, 1940–1941’, South African Historical Journal (1992).

Footnotes

- C. Marx, ‘“Dear Listeners in South Africa”: German Propaganda Broadcasts to South Africa, 1940–1941’, South African Historical Journal (1992). ↩︎

- Sunday Times – Page 2, Nazi Radio man took part in Hess Service: 30 August 1982 by De Wet Potgieter and Jannie Lazarus ↩︎

- German War Cenotaph Pretoria West Cemetery – eGGSA Library ↩︎

- Neville Petersen recalls, Nagkantoor Facebook Social Media Group ↩︎

- Sunday Times – Page 2, Nazi Radio man took part in Hess Service: 30 August 1982 by De Wet Potgieter and Jannie Lazarus ↩︎

- Ibid ↩︎

- Idid ↩︎

- Grave of Hitler aide destroyed – 22 July Al Jazeera News 2011 ↩︎

Photo copyright of Rudolf Hess Commendation Pretoria: Neville Petersen.