The Battle of Cassinga was the very first South African airborne attack, it was also the first full-scale airborne attack in Southern Africa. The target was a South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO) military base at the former town of Cassinga in Angola on 4 May 1978. As it was a ‘first’ in many respects it would also carry with it many learnings and many controversies.

Upfront let’s dispel with the untruths and challenge the prevailing myths and truths. The Battle of Cassinga is today mourned in Namibia as a public holiday, politically it is referenced as an Apartheid “massacre” of ‘innocents’ – the deliberate targeting of refugees and civilians in a refugee camp. However, this is a political narrative to gain political currency and simply put this is a myth, it is an untruth.

That civilians were killed in the cross fire during the battle, unfortunately that is truth, that a large number of civilians died at Cassinga, that is also a truth. That civilians are very often the casualties of war, any war the world over, this is also unfortunately a prevailing truth.

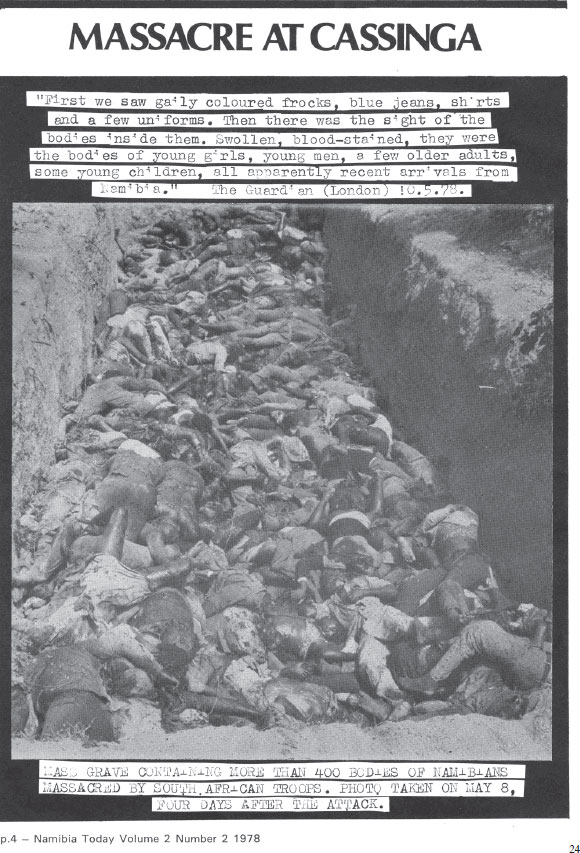

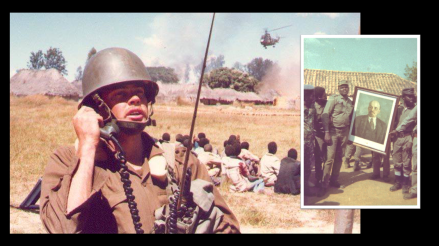

Also, a truth is that there are extensive records and photographs covering the SADF’s planning and actions around the operation (declassified since the change of government in 1994), no SWAPO records exist at all. The only other things that exist is the photographic evidence of a mass grave, which was re-opened after the battle for journalists to take photos, photos of the camp taken by journalists prior to the attack showing a military recruitment base with a large component of civilians in support of it and photos taken by the SADF Commanding Officer on the ground – Colonel Lewis Gerber, from the Camp Commander’s desk which show a SWAPO recruitment operation at Cassinga.

That Cassinga was a military base housing PLAN (SWAPO military personnel) there is absolutely no doubt, and therefore it was a legitimate SADF military target, that is also a truth. That there were misjudgments in planning and execution, like any military operation anywhere, this is also a truth. That the definition of what type of military base it was i.e. a recruitment depot, that definition was unclear to the SADF at the time of striking it and that is also an unfortunate truth.

So let’s have a look at how this Operation, Operation Reindeer, stacks up as a military battle, and lets examine how civilians came into the cross-fire.

A Military base or Refugee Camp?

Aside from the overwhelming volume of Intelligence gathered by the SADF prior to the attack pointing to the fact it was a legitimate military base and target, the case was taken to The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in the 1990’s. The TRC themselves challenged all sides of the story, and it’s the TRC records which found Cassinga base to be the following:

A SWAPO (PLAN) unit posted at Cassinga consisted of approximately 300 male and female PLAN cadres. The military section of Cassinga was easily partitioned from the non-military sections. The overall commander of PLAN in town was Dimo Amaambo, who responsible for the co-ordination of all PLAN actions in Southern Angola, including incursions into South West Africa/Namibia. A headquarters such as Cassinga was second in importance only to Lubango, which was the overall SWAPO military headquarters in Angola. Aside from the system of trenches and bunkers, defensive equipment included two ZPU 14.5 mm anti-aircraft guns, one ZU-23-2 23 mm gun, and around one or two ZSU 12.7 mm guns. These were all capable of being used in a ground attack role.

The simple fact is that the SADF encountered trained and armed SWAPO (PLAN) combatants, large AA guns, defensive structures, SWAPO military commanders and depots full of weapons and ammunition of all sizes. This was a military base, but what sort of base?

So where does this argument of ‘refugee’ and ‘refugee transit camp’ come from?

According to one source, in the weeks preceding the attack, civilian numbers were growing rapidly inside Cassinga. This build up consisted of a number Namibians going into ‘exile’ to join SWAPO in the months preceding the attack and the intake in this camp of these civilian ‘exiles’ joining SWAPO was particularly high. It was normative at the time that a civilian recruit joining SWAPO/PLAN as a combatant often went into ‘exile’ with his or her family (in whole or in part) in support.

A truck usually picked up these SWAPO/PLAN recruits and their civilian entourage at Cassinga and took them onward to their training bases in Jamba and Lubango. Cassinga operated as a Recruiting Depot and a Holding Depot to verify recruits. This truck to take them to their training bases did not arrive in the preceding weeks before the attack . The result was a bottleneck at Cassinga of people (Recruits, Civilians and Armed Soldiers) who under normal circumstances would have left the camp within days.

Another source agues that the civilians in the camp were made up of both soldier’s family members and dependents and some 200 civilians ‘abducted’ by SWAPO in northern South West Africa a few months earlier, and brought to Cassinga in a bid to convince UN aid agencies that they needed food and funding, which they duly received.

The ‘abduction’ of civilians for ‘re-training’, especially children, was a tactic to build numbers and used extensively by ‘liberation movements’ all over the Southern Africa in the late 70’s. The ‘liberation movements’ on the other hand argue that these were willing exiles fighting the cause or that it was necessary to deconstruct tribal people of their colonial indoctrination.

What is also telling as to the military nature of the camp and the indoctrination into the military of incoming ‘exiles’ comes from SWAPO photographic and witness evidence of how they conducted the daily parade and roll call. It was held on a parade ground near the SWAPO (PLAN) offices. This source recalls that all would assemble in the groups in which they had arrived at Cassinga, each of which was organised according to ‘sections’ and ‘platoons’ with the earliest arrivals in Cassinga queuing first and the most recent queuing last. They would march on, the SWAPO Commanders would march on last, after liberation songs were sung a roll call would be taken, the commanders then handed out the daily tasks and finally dismissed the parade. It is reasonable to assume from this account that ‘exiles’ entering the camp where in fact ‘military recruits’ and treated as such.

So, whichever way it’s looked at, there was a large military camp and there was a large contingent of newly arrived Namibian civilians at Cassinga (how many were SWAPO ‘exiles’ or PLAN ‘new recruits’ will never be known) and a very large number of family members and dependents of the PLAN combatants at the base. That the military planners in the SADF had accounted for the unusual ramp up in civilians numbers of ‘exiles’ just prior to the attack, the sad truth and answer is no, they were not really aware of it. In fact ‘Intel’ for the SADF pointed to a PLAN combatant base, when it should really have been pointing to a PLAN military recruitment depot complete with a civilian and untrained recruit ensemble.

Errors in Planning

In the truth that errors occurred, some started in the planning phase. Reconnaissance air-photo interpreters of the Cassinga military base put the wrong scale on some of the maps that were used in the planning, despite the altimeter readings being clearly visible in the original reconnaissance photographs.

Consequently, the Air-Force planners overestimated the size of the Drop Zone (DZ) believing it was long and wide enough to drop the paratroopers, when in fact it wasn’t. This ‘scale error’ also mis-positioned the ‘Warning’ and ‘Drop’ points on the run-in to the drop. Compounding this error, the pilot of the lead aircraft was momentarily distracted by the effects of the bombing, and issued the ‘jump’ signal a few seconds late. The net effect was that many SADF paratroopers overshot their intended Drop Zones, many landing beyond the river – and some in it.

The SADF also underestimated the Cuban military presence in the area, In briefing the strike aircrew, the SAAF Chief of Staff Intelligence was specific that there was no known large Cuban military formation within 130 km of the Cassinga base. They had intelligence that pointed to Cuban armour and that some 144 personnel was present at the village Techamutete 15 km south of Cassinga. To this end they planned communication jamming (which proved a wise decision in the end as it resulted in a delay) and a detachment was earmarked to ambush any Cuban armour on the road from Techamutete.

However unknown to the SADF planners was that this force was somewhat bigger than anticipated, in fact there was a well sized Cuban mechanised battalion at Techamutete consisting of at least 4 T-34 tanks, 17 BTR-152 armoured personnel carriers, 7 trucks and 4 anti-aircraft guns, accompanied by around 400 Cuban troops.

The Devastating Opening Bombing Run

The attack opened with a SAAF Canberra bombers and SAAF Buccaneer bombers hitting the target. Timed for 08:00 to coincide with SWAPO’s daily roll-call on the parade ground, most of the people in the camp were assembled in the open when the Canberras initiated their low-level bomb run. This was followed by the Buccaneers and then SAAF Mirage IIIs. Fragmentation and conventional 1000lb bombs hit a zone of some 800 metres by 500 metres, causing most of SWAPO’s and civilian casualties and ‘hard target’ building destruction on the day.

The bombing run, according to the SADF Paratroop Commanders when they go to the base, did almost all of the damage. Colonel Gerber was to report on a disturbing sight of what he thought were many old-school brown ‘cardboard’ school suitcases littering the drop zone, on closer inspection these turned out to be bodies whose limbs and heads had been severed by the intensity of the cluster bomb shrapnel and sonic blasts, the lone torsos looking like those old suitcases.

The Shambolic Drop

At 08:04, 367 SADF ‘Parabats’ (Paratroopers) were dropped from 6 aircraft. Due to the reconnaissance photo scaling error, and obscured pilot visibility of the tracking and distance markers (caused by smoke from the bombing) the drop was a shambles. Nearly all paratroopers did not land on the intended target zone, many been scattered into positions that put them into serious danger. Some dropped right on top of the enemy, some landed kilometres away from their intended positions, some in trees, some into tall maize fields, others into the river and some on the wrong bank of the river.

The resultant confusion caused numerous delays, ruining the schedule of the ‘drop-to-contact’ plan, and much of the advantage of surprise. As a result a number of top PLAN commanders, including Dimo Amaambo and Greenwell Matongo (two principal targets of the attack) escaped (Amaambo later became the first head of the Namibian Defence Force in 1990).

The loss of the element of surprise, also allowed the surviving SWAPO (PLAN) soldiers from the bombing ample time to set themselves up in the extensive trench and bunker system that surrounded the camp. Instead of the short, sharp skirmish planned, the attack was now going to be an extended affair. The camp defenders brought their anti-aircraft guns to bear on the SADF ‘Parabats’ and onto the aircraft, these powerful guns were not all silenced for some hours to come.

Regrouping and on the Attack

After regrouping the ‘Parabat’ companies commenced the assault, training and professionalism of officers and men on the ground played a key role in consolidating and adapting their initial tasks to the changed circumstances. Instead of attacking eastwards as initially planned, the two companies attacked the base in a northerly direction.

Initially, they encountered very little resistance, though this changed dramatically once sections of paratroopers neared the centre of the base. Heavy sniper fire was directed at the paratroopers from a number of trees inside the base, they were subjected to B-10 Recoilless Rifle fire, and some PLAN soldiers had regrouped, using houses as cover from which to fire at the SADF paratroopers, critically wounding two paratroopers.

However, the paratroopers faced their greatest challenge when they were fired upon by a number of multi-barrel anti-aircraft guns now been used in the ground role. This brought both assault companies to a complete halt. A SAAF Buccaneer tasked with Close Air Support could not conduct a strike on the guns for fear of hitting the paratroopers close by.

Colonel Breytenbach then ordered the commander of D-Company to take some men and work up towards the guns by attacking the trenches to the west of Cassinga. He also ordered the mortar platoon to begin attacking the guns. In reality according to Colonel Gerber, these particular guns pinned down Colonel Breytenbach and his men for some time, literally preventing them from taking any significant role until this gun was ultimately silenced toward the end of the battle. Colonel Gerber’s section, having reset their assault, advanced from the south and met little resistance until in the town itself and here they were able to quickly over-power the defenders.

Civilians in the Trenches

Situated all around Cassinga was a network of trenches, these had been identified in the air photography intelligence before the battle, this network was complex, expertly laid out and very extensive and its one of the reasons why SADF planners believed the Cassinga to be a well defended and significant military base.

Colonel Gerber in his sections advance on Cassinga did not encounter any significant resistance from the trench network facing him, although he did notice some civilian dead in the trenches which he concluded were people trying to take cover in the tenches during the bombing run or mortally wounded people in the bomb run who had may their way to the trenches.

Different story for D-Company’s assault on the trench system facing them, as these had been occupied by PLAN combatants opening fire on them. Upon entering the trenches, the Paratroopers from D-Company were surprised to find a number of civilians in them in and amongst the combatant SWAPO (PLAN) fighters.

At the TRC hearings, the witness accounts from the paratroopers involved maintain that these civilians were being used as human shields by the SWAPO combatants taking cover inside the trenches. Accounts from SWAPO maintain that the civilians of Cassinga had taken cover in the trenches to protect themselves from the bombing and shooting.

In either event, the fact remains that civilians had found themselves in the trench network and were mixed in with SWAPO fighters who immediately opened fire on the paratroopers, leading the paratroopers to enter what they described later as a mode of “kill or be killed”, in which preventing the deaths of the civilians in the trenches became impossible.

The paratroopers moved successfully through all the trenches and strong points up to the guns and after the fall of the guns, all major resistance in Cassinga ended.

Mopping up and extraction

With hostilities over in Cassinga, the paratroopers immediately set up a HQ and Aid-Post next to the SWAPO hospital, and began treating the worst of the injured.

In ‘mopping up’ in Cassinga the paratroopers recovered a relatively small number of mainly Soviet weapons, these included a B-10 Recoilless Rifle, AK-47, AKM and SKS Assault rifles and carbines, boxes of RGD-5, RG-42 and F1 Hand Grenades, some TM-57 Anti-Tank Mines, RPG-7 Anti-Tank Rockets and 82mm B-10 recoilless Rockets still in their tin transit canisters. Uniforms (Soviet and East Bloc supplied) and combat boots, AK-47 and AKM Bayonets and some crates of AK-47 Ammunition were also recovered. However, as can be seen in these photos of the PLAN arms recovered, the quantity was small.

Of extreme interest in the mopping up operations, on approaching the head quarters building, they found some children hiding and were able to get them to safety. It was a small facility, a room really, and once secured the desk of the Cassinga camp commandant was searched and documents and photos of camp life extracted.

The first wave of SAAF Puma helicopters extracted half the ‘Parabats’, leaving the remainder to continue to mop up while waiting to be evacuated themselves. Now at half their strength, the Parabats were warned by a circling SAAF Buccaneer in Close Air Support (CAS) that a column of twenty armored vehicles was approaching the base . The Cuban mechanised battalion from nearby Techamutete was now on the counter attack.

The Cuban Counter Attack

During the air drop attack phase, D-Company had already dispatched the anti-tank platoon to lay a tank ambush on the road to Techamutete. The lead Cuban Soviet era T-34 tank was destroyed by one of the anti-tank mines, while the paratroopers destroyed four of the BTR-152s using their RPG-7s. They also killed approximately 40 of the Cuban troops before making their ‘fighting retreat’ back along the road towards the Helicopter Landing Zone.

This was a grave threat to the few remaining Parabats. Their LZ’s came under tank fire and APCs full of Cubans threatened to swamp the remaining Parabats. Support was called in to rescue the beleaguered paratroopers, a Buccaneer and two Mirage III’s appeared, the Mirage III’s destroying a further 10 BTR 152s before running low on fuel and returning to base.

The sole Buccaneer remained and destroyed at least two tanks, an anti-aircraft gun (which as firing at it) and a number of other vehicles.

The Buccaneer ran out of ammunition at this point, and this coincided with the arrival of the 17 helicopters to extract the remaining paratroopers in the second wave. The Cuban armoured column then advanced on the helicopter’s landing zone. In a desperate attempt to prevent the Cuban tanks from firing at the vulnerable helicopters and the assembling South African troops waiting to be picked up, the Buccaneer pilot dived his aircraft dangerously low, nearly hitting trees as he flew close over the top of the tanks in mock attacks. This brave and dangerous action by the pilot disorientated the Cuban tank crews and forced them to break off their developing attack on the paratrooper’s’ positions.

The destruction of the Cuban column

Ten minutes after the last of the SAAF helicopters took off, two of the Puma helicopters were directed to return to Cassinga, as it was feared that some of the paratroopers might have been left behind. They spotted a group of people huddled together, but closer inspection revealed that they were the 40 prisoners of war who had been mistakenly left behind. No more paratroopers were found.

In the mid afternoon SAAF Mirage IIIs returned to Cassinga, and once again strafed the Cuban vehicles that were still on the road. About a kilometre south of Cassinga, another Buccaneer attacked another column of vehicles, coming under heavy anti-aircraft fire in the process.

In the late afternoon SAAF Buccaneers and Mirages surprised the Cubans moving through the ruins and destroyed more Cuban T-34 tanks and anti-aircraft guns.

The result was that by nightfall nearly the entire Cuban battalion had been destroyed, accounting for Cuba’s biggest single-day casualty rate during its military involvement in Angola up to that point.

A complete Angolan tank brigade relief force, arriving at dusk, was too late to have any impact and found only scenes of destruction at what had once been Cassinga.

Aftermath

According to an Angolan government white paper, the official toll of the Cassinga Raid was a total of 624 dead and 611 injured comprising civilians as well as combatants. Among the dead were 167 women and 298 teenagers and children. Since many of the combatants were female or teenagers and many combatants did not wear uniforms, the exact number of civilians among the dead could not be established.

The South Africans declared the attack on Cassinga to be a military success, and it set the SADF strategy for dealing with SWAPO bases in Angola for the next 10 years (although in future, the larger strikes were primarily armoured based not airbourne). A SWAPO propaganda campaign on the other hand labelled the attack on Cassinga as a civilian massacre.

The position of SWAPO and all the organizations and governments that were supporting it by 1978 benefited from the moral outrage incited by a ‘surprise attack’ on a ‘refugee camp.’ In the aftermath of the raid, SWAPO received unprecedented support in the form of humanitarian aid sent to it from sympathetic governments.

It was however clear to the South Africans that Cassinga was a military facility rather than essentially a refugee camp or refugee transit facility, as SWAPO claimed. They had the proof.

The Mass Grave Propaganda Campaign

Although a military success, politically it was a disaster for the National Party government of South Africa. SWAPO and Angola press statements described the base as a refugee camp and claimed the SADF had slaughtered 600 defenceless refugees.

The bodies were buried in two mass graves. Pictures of one of the mass graves (the larger one) was used extensively for propaganda purposes, and for many people these pictures became the imagery and symbology associated with Cassinga.

Taken from the grave’s edge, the mass grave photos are close enough to the corpses for individual bodies, and in some cases the clothing, wounds and flies covering them, to be discernible. The photos demand an emotional reaction, the photographs are set in such a way as to look like a WW2 styled premeditated massacre, appearing as if the SADF had dug a grave and piled in the ‘civilian’ bodies.

SWAPO propaganda in the weeks following the attack used “text” on posters to draw attention to the ‘civilian’ qualities of the bodies, the suffering of Namibians under colonialism, and the violence committed against oppressed people in other settings. In so doing, they associated the mass grave at Cassinga with the history of the ‘refugee’ camp.

In truth the SADF paratroopers did not dig a mass grave, nor did they have the heavy equipment to dig such a grave, the urgency of the extraction meant they left most of the dead where they lay.

The holes used for the mass graves were originally built by SWAPO as food storage spaces. Following the attack, the survivors at Cassinga, together with Namibian, Cuban and Angolan soldiers, collected the dead scattered in and around the camp and laid them to rest in the two holes and interned them in with sand and soil closing the holes.

Some days later, survivors and others were instructed to re-open the larger of the two graves to show international journalists who would be arriving at the camp on 8th May. People took turns digging up the sand and brushing it away from the bodies so that it would not obscure the journalists’ view.

The attending journalists noted that they assumed that the larger grave had not yet been covered and made no mention of how the grave was prepared for them.

A detailed examination of the mass grave photographs indicates that the bodies are those of adults more than teenagers, though some of them are certainly young adults. The overwhelming majority of them are men, with only a few women. Most of the men are wearing uniforms and there is little evidence of the ‘brightly coloured frocks’ although several of the photographs are in colour.

In conclusion

The truth and reconciliation commission special report on Cassinga could not attribute any ‘war crimes’ to any specific SADF personnel and officers taking part in attack on Cassinga.

In the end the Operation can be regarded as a military success, it was a classic daring paratrooper styled assault with the usual high risk associated with it, if it had gone wrong it would have gone very wrong. In total the SADF casualties where very light for an assault of this nature.

There were however some fundamental failures. Primarily this was the failure of the SADF Intelligence Services to account for the high number of civilians in the camp in the lead up to the attack, and failure of SADF Planners to envisage the high probability of these civilians entering into the cross fire or been subjected to the bombing run’s killing zone.

No modern statutory military force bound by the Geneva Conventions intends to purposefully kill civilians, and the South African Defence Force was no different. However the simple truth is that using fragmentation bombs at the beginning of the assault accounted for most of the civilian casualties. ‘Dumb’ ordinance like this is indiscriminate (‘smart’ bombing had not been invented in the late 70’s) and in this sense such bombing is no different to WW2 ordinance and like the Allied WW2 bombings it is a sad truth that many civilians are killed when using it. The sheltering of civilians in the trenches from the bombing added to the tragedy which was to come.

To put aside the obvious tragedy of civilians in the cross-fire, we also need to be truthful when reviewing Cassinga, there is still the very awkward question of what qualifies a ‘civilian’ and what qualifies a ‘civilian in support of combat operations’? It’s one that modern reviews of Cassinga tend to skirt well around, but the stated SWAPO survivor testimony points to a Cassinga as a ‘exile’ clearing camp of people making their way into Angola to be trained and join the war effort, in this sense they qualify as ‘military recruits’ and therefore a wartime target by any definitions of it.

Then there is also the thorny question of civilians supporting armies by way of preparing food and other resources which would otherwise be considered as an auxiliary military role. This argument was used to justify the ANC MK bombing of the Southern Cross Fund offices (a civilian support group of the SADF providing care parcels) to qualify it as a ‘military target’. It’s was also an argument used by the British to inter Boer families supporting commandos in the field during the 2nd Anglo Boer War – with devastating civilian casualties.

That said no doubt amoungst the dead were actual ‘innocents’ too, especially children and family dependents, which by any account of war is always regrettable, to both sides. This ‘fog of war’ is a shared trauma that haunts the survivors of Cassinga and SADF Paratroopers alike.

In the end, although Cassinga was a military success, it was a political failure. The South African government sought a highly aggressive settlement to Namibia with the agreement to hit the base at Cassinga and not a passive or negotiated one. The backlash of world-wide condemnation was something many of the National Party politicians did not really foresee.

Today

After independence, the new government of Namibia declared 4 May as “Cassinga Day” a public holiday to commemorate the loss of life. In 2007, the names of the Cuban soldiers who were killed were carved into the wall of Freedom Park in South Africa.

Official celebration of this event by the SANDF ended in 1996. Veterans of the various South African parachute battalions still privately commemorate Cassinga Day, and many stand in remembrance of all who died that day and all those traumatised by it – from both sides of the conflict.

SADF Honour Roll

71384234BT Rifleman Edward James Backhouse from 3 Parachute Battalion. He was 22.

68546134BT Rifleman Martin Kaplan from 2 Parachute Battalion. He was 25.

70510813BT Rifleman Jacob Conrad De Waal from 2 Parachute Battalion. He was 23.

65383390BT Rifleman Andries Petrus Human from 3 Parachute Battalion. Reported Missing in Action after jumping from the aircraft at Cassinga.. For administrative purposes, he was officially declared dead on 22 January 1980. He was 29. Recent discovery points to a grave dug by a village headman to bury him and funds are been raised to examine this and bring him home.

May all the people lost in this attack rest in peace, and if you had to ask any of these veterans of this attack and who have really ‘seen’ war, they mourn the destruction and loss caused in all war, civilian and combatant alike.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens. Colour SADF photographs of the battle, and photo of Edward Backhouse – credit and copyright to Mike McWilliams, with his kind permission. Other images of the battle including Mike under his canopy copyright Des Steenkamp.

Collaborated input on this article by Colonel Lewis Gerber, OC 3 Para Bn, SO1 Ops at 44 Para Bde and SSO Airborne at CArmy (Retired)

Images for the Camp Commandant’s desk courtesy and thanks for Colonel Lewis Gerber, so too some of his maps and photos.

Source Wikipedia, South African History on-line, On-Line veterans SADF forums and witness accounts. Truth and Reconciliation commission reports. Remember Cassinga by Christian A Williams.

Nice summary. It’s really a pity there are spelling and grammar errors.

LikeLike

This is a very 1 sided story

A lot of innocent helpless Namibians where killed.

SADF has a lot of innocent blood on their hands

LikeLike

actually this is very detailed and factual account. even the TRC agreed and they where on a witch hunt to crucify an SADF members involved. fact that they could not only servers to strengthen the fact this was a legitimate target. if you want to blame anyone blame the SWAPO for using civilians as human shields

LikeLike

yes it appears one sided but you had to be there to know the truth. Learn your history from both sides. Always remember that the general media like today support who they see as the underdog. That the media are not always truthful nor wish to expose the truth. In short never believe what you read in the mainstream.

LikeLike

Shame.

LikeLike

Were you at Cassinga ? I on’t think so! Too many people comment on heresay!,,,

LikeLike

I dint think you know wha you are talking abkout. You want to spread propoganda. No innocent person was killed .NOT ONE. I WAS ALSO THERE.

LikeLike

Would you please supply details. It’s easy to make sweeping remarks but such remarks don’t come across as believable because it’s unsubstantiated.

Thank you.

LikeLike

Helpless Namibians with AK 47 rifles, mortars and anti aircraft guns ne !!!!

LikeLike

If you read “a Bridge too far” you will realise that para attacks are most often tragedies – Cassinga was a success measured by WW2 standards!!!!!

LikeLike

Genl Mac Alexander wrote a Masters thesis on Cassinga. It is a critical analysis of the opetation ad an airborne opetation. Should be able to access thesis on internet.

LikeLike

Could you provide more details of the thesis; title, date, university, etc.

LikeLike

Here is the link to the thesis: https://www.sa-soldier.com/data/09-SADF-links/cassinga_raid/00dissertation.pdf

LikeLike

Also only his point of view. I don’t agree with all due to personal issues.

LikeLike

Hi Anton – What is your personal view of Cassinga ??

LikeLike

Excellent historical account Peter.

Thank you

LikeLike

don’t worry about the Propaganda about alleged civilians. They were there voluntarily or used as human shields. in the latter case it was PLAN’s doing SADF is not to blame

LikeLike

Pingback: 4 Mei 1978: Penyerangan Pasukan Payung Afrika Selatan ke Basis Gerilyawan Marxist SWAPO di Cassinga - Sejarah Militer