Seems there is a lot of social media chatter surrounding Albert Blake’s new Afrikaans book on Jopie Fourie. One Afrikaner pundit after reading the book declaring anyone not familiar with the ‘truth’ about Jopie as a ‘Volksheld’ and the Rebellion is now a liar and this in his world includes any other qualified historians, other than Albert. Albert Blake himself even declaring his new work is the definitive one and the only medium to be referenced (problem is, only people who are fully literate in Afrikaans can read it).

There is undoubtably some truth in the old saying ‘history is written by the winners’, however very often the ‘plucky loser’ is a perennial favourite of propagandists, myth makers and entertainers (including Hollywood), they are often romanticised and idealised, given virtuous christian outlooks, a civilised veneer and great martial abilities – the little guy taking on the big bully. This is especially true of the 1914 Afrikaner Revolt and Jopie Fourie … and many of its local Afrikaner historians and laymen enthusiasts.

All this Boer romanticism and the portrayal of old Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) as a benign place for a freedom loving people merely wanting it back – a foreign example of this is the Confederacy in the American Civil War (1861 to 1865), and here a Royal Historical Society historian, Chris Ash made a rather humorous comment and it rings especially true:

“Until very recently, they were certainly viewed by most as the more ‘glamorous’ of the two sides… gallant, good looking Southern gen’lemen who ‘frankly didn’t give a damn’, galloping off to fight against impossible odds against a massed industrialised hordes of a faceless enemy who wanted to end their bucolically halcyon way of life. Throw in a few gorgeous Georgia Peaches – called things like Emma-Lou and Daisy-Belle – all with heaving bosoms barely contained by beautiful ball gowns, and you’ve got all the makings of a heroic myth of doomed failure… well, as long as you ignore that the South started the war, and that they were fighting to retain slavery!”

There is an old proverb, and its especially true to historians “never meet your heroes” .. because in getting to the actual historical figures, you need to analyse who they are as people, how they view the society they live in at the time, and how that society views them. In their context of their time, you as as historian need to overcome your prejudices and start to look at things in a critical way.

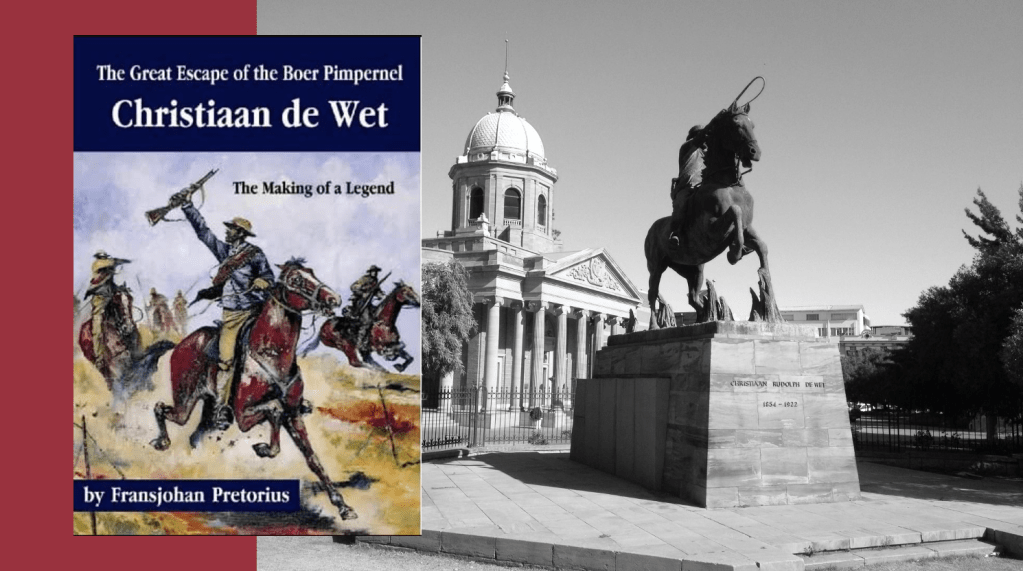

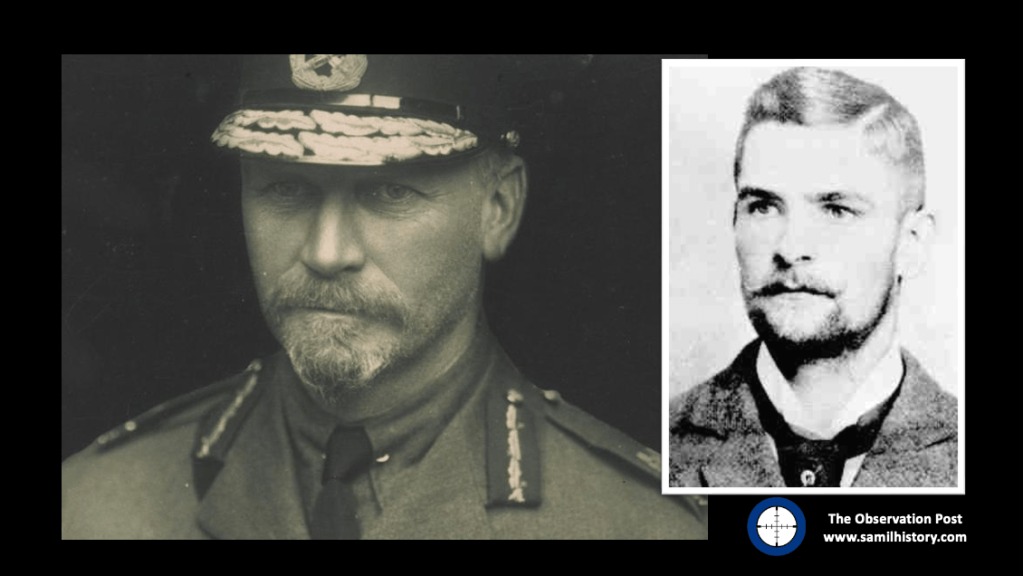

This is especially true if you grow up with a ‘rebel’ as a person central to your entire identity, because as true as the sun rises that ‘rebel’ is going to be controversial and for good reason – and very much of this hero will depend on what they are fighting for … and “freedom” is the usual caveat … but then you start to really meet your hero when you ask the next question “freedom for whom?” Here it is where the hero worship of the 1914 Afrikaner rebellion leaders like Christiaan de Wet, Manie Maritz, Jan Kemp, Christiaan Beyers and Jopie Fourie starts to wobble somewhat .. sure they are fighting to free themselves from British oppression – they all said so, including Fourie the day before his colleagues shot him, but he like the others – Maritz, de Wet, Kemp and Beyers are also fighting for their stated aim of the Rebellion, and that’s a completely different kettle of fish.

Now, there is a small problem with the history of the Rebellion – and one of them is the complete lack of history books in English and even less written at the time of the revolt – the complete Afrikaner romanticism of the rebellion all comes much later with the advent and rise of Afrikaner nationalism and a plethora of Afrikaner academic papers, novels and books.

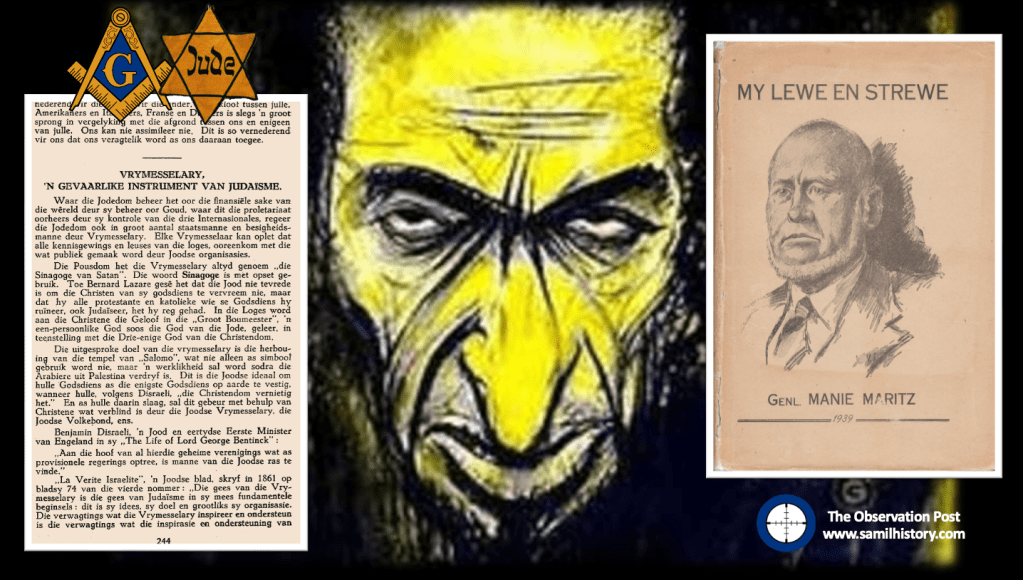

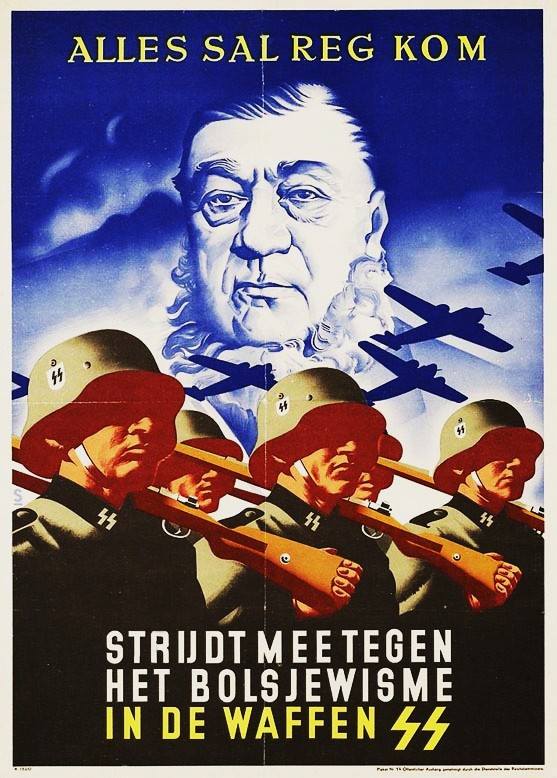

For simplicity sake, there is a ‘English’ side to the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion story – the majority in the country if we consider all races and nationalities caught up in the Rebellion and there is a ‘Afrikaans’ side of the story, a minority – driven initially by Hertzog and his breakaway cabal of pro Republican Afrikaner Nationalists from the Botha/Smuts South African Party (SAP) in 1914 and then it is heavily driven by a far right grouping of ‘pure’ nationalists after their break with the Hertzog/Smuts Fusion before World War 2 (1939-1945) – and they went about using mass media, aligned academics in ‘Afrikaans’ universities and all manner of propaganda to ‘set the Rebel story strait’ – even Radio Zeesen from Nazi Germany with its renegade Nationalist broadcasters went full tilt at glorifying Fourie, the Rebellion and demonising Smuts during World War 2.

For any historian to take a grip on the 1914 Afrikaner Revolt in 2024, the bank of both primary and secondary source becomes invaluable and it sets up the validity of what you are going to say, ensure whatever it is holds up to academic scrutiny by your peers. In respect to using both primary and secondary sources, the closest you are to the historical figure in question the more accurate and valid the work – so here we find original accounts by people involved in the events as the key.

There has only ever been one comprehensive history book written in English on the Afrikaner Revolt and luckily for us its very close to the events of 1914, it is published a year later in 1915 and its written by a journalist very closely tied to the whole 1914 Revolt having interviewed the principle characters personally and been witness to the events himself. The book is called “The Capture of De Wet” and it’s written by PJ Sampson.

Now, unlike all the Afrikaner historians writing for a Afrikaner market on the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion who come after PJ Sampson (many come decades after him), Sampson is just not interested in presenting a counter-case for High Treason for the Rebellion – the old Afrikaner Nationalist’s “volks-veraairer” versus “land-veraairer” (traitor to your ‘people’ as opposed to traitor to your ‘country’) argument which has been going round and round Afrikaner family kitchen tables for 110 years and still rages on – nope, Sampson records none of that, in fact he sees the ‘treason’ argument as clear cut one in 1914 and the execution of Fourie as inevitable.

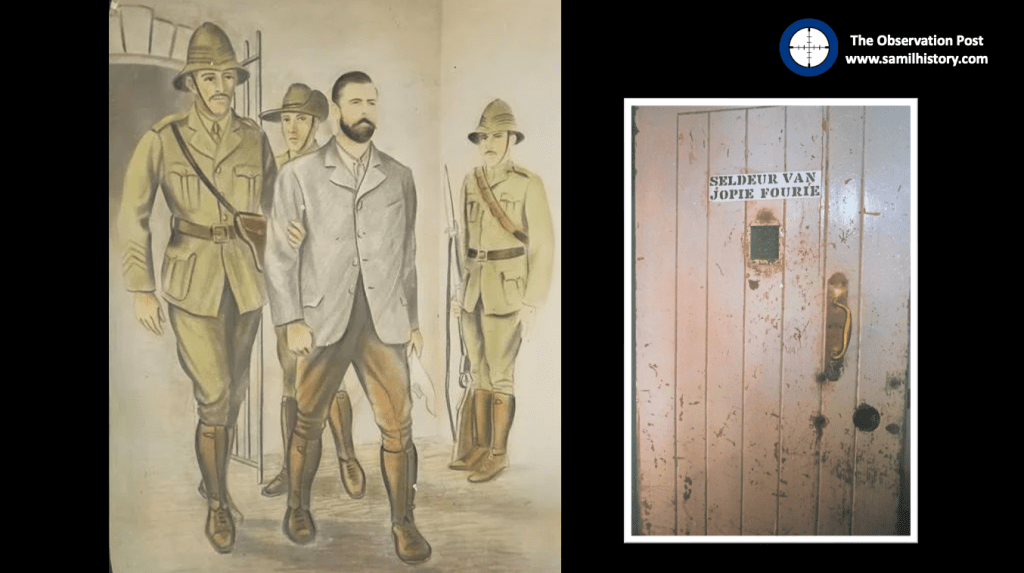

Sampson is not alone, I published an article on my visit to Scapa Flow where unarmed German sailors responsible for sinking their surrendered Imperial fleet were executed for sedition on the spot as they came ashore – some by way of bayonet. 1914 and World War 1 (1914-1918) veterans looked at treason and the execution of traitors very differently to the way we look at it now. Fourie is lucky he got a trial and not a drumhead trial and on the spot execution, at that time if you committed treason or sedition, with war declared and domestic state of emergency regulations in place – you got dragged through an administrative formality which lasted barely a day, then taken out back in the morning and shot – that is what happened to Fourie and that was the way of things then.

I’m also not alone, one of the principle characters in the Jopie Fourie story is General Jan Smuts, Jan Smuts himself would regard Fourie as having “shed more blood than any other officer.” With the rebellion lost, Beyers drowned and General de Wet surrendered … Smuts would say:

“Only Fourie’s band remained contumacious. Twelve of our men were killed at Nooitgedacht. There was no justification for that. Some of them were shot at a range of twelve yards … A court martial was appointed, strictly according to military law. One of its members told me he felt compunction about serving, because he was a friend of Fourie’s. I replied that that was an additional reason why he should be on the tribunal. On Saturday Fourie was unanimously condemned to death…”1

Smuts would go on to say:

“Had I refused to confirm the sentence, I could not have faced the parents of the young men who met their deaths through Fourie’s fault. There is something to be said for many a rebel, but in this case I conferred a great benefit on the State by carrying out my most unpleasant duty..”2

Smuts remained convinced that a fair trial had taken place, the correct legal framework in place, as to all the rebels Fourie was an exception and Smuts was unrepentant in the outcome, in fact he saw Fourie’s execution as unavoidable and it was his duty to see it through – his attitude had hardened, his son – Jannie Smuts in his biography of his father would write very little on Fourie in the entire appraisal of Jan Smuts’ life and career, Fourie is barely a footnote, a wayward rebel, nothing more.

A lot is also written about by Neo-Nationalist historians and disgruntled Afrikaner commentators on Smuts’ so-called “refusal” to entertain last minute efforts to intervene and reprieve Fourie, Jannie Smuts Junior is however dismissive of this and confident his father “would not have interfered in the course of justice” in any event. So this entire episode in the story really is a non-starter.

In fact Sampson views Fourie as somewhat deluded and misled, he even sets aside an entire appendix to demonstrate the flaws in Fourie’s understanding of history, his thinking and the flawed nature of his defence testimony, which Sampson tears apart completely and simply dismisses as unreasonable and deluded – instead Sampson takes pity on Fourie as someone who cuts a tragic figure having been misled by less scrupulous men like Maritz, his execution a foregone and unpleasant conclusion.

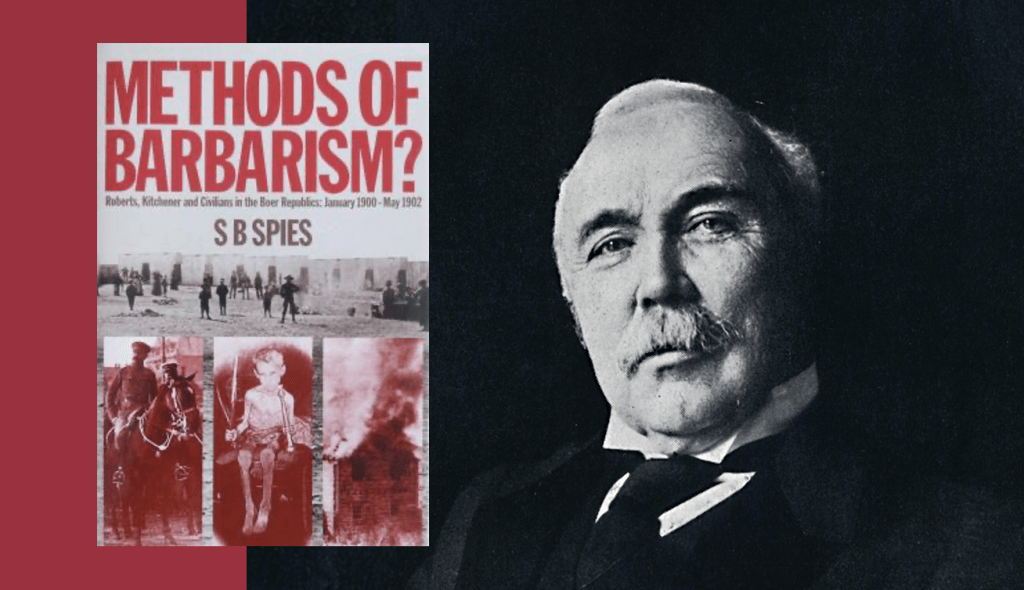

The main thrust of Sampson’s book is however on the objectives, mission and stated aims of the Rebellion. Although the long-standing Anglophobia caused by the Boer War is considered, it is not Sampson’s focus, simply because he, like many English commentators of his time, they understand the tragedy of the concentration camps and the pain they caused at face value, they see the deaths in context of measles and typhoid epidemics which sweep the camps due to hardship and unsanitary conditions brought about by war – a tragedy and nothing more. The ideas of ‘genocide’ and ‘murder’ of the Afrikaner nation are completely foreign to Sampson and other British historians like Amery of the time and this thinking would qualify fantastical thought at best.

Sampson is more interested in the politics of the Afrikaner Revolt and the politics of the leaders taking part in it, the political circumstances in South Africa in effect (and less so the geo-political circumstances). Here Sampson argues that the ‘colour blind franchise’ and human rights for ‘natives’ are also key motivations for the rebellion – the rebels intent on maintaining a Afrikaner led hegemony, an oligarchy based on “Krugerism” as an ideology – which means no franchise, emancipation and limited human rights (if any) to anyone of colour. The declaration of war presents an opportunity for these Afrikaner leaders, with the assistance of Germany, to take over the whole of South Africa and implement this political construct of theirs, much like the post American Civil War traitors like John Wilks Booth and his rebels in 1865 trying to “raise the South” again and reclaim slavery. Sampson refers to the animosity between the ‘Free State’ Boers like Christiaan de Wet against the ‘Transvaal Boers’ of Smuts and Botha over the colour blind franchise, de Wet fearful that Smuts and Botha are ushering it in and it’s all very unacceptable to him.

Now, to anyone paying attention to the history, the colour blind qualified franchise across the entire country (not just in the old British Cape Colony) is one of the key demands by the British for a peaceful settlement of the South African War (1899-1902) ie. Boer War 2. It is the only clause that is dropped out the Peace of Vereeniging agreement as the Boers absolutely refuse to abide it and its a deal breaker. It is only dropped on the proviso that a future Union government, when it is granted self governance, will implement it – Smuts assures the British that he is the man to see it through and all the Boer signatories to the agreement promise they will address it when a Union and self determination is declared (this includes de Wet, Kemp and de la Rey et al)

The South African Union and self determination/responsible government is granted by the British to Botha’s ’South African Party’ (SAP) in 1910. However inside the SAP, Smuts and Botha are simply unable to move on the colour blind qualified franchise as the likes of de Wet and Hertzog will have none of it, 4 Years later it’s beginning to become a problem as an entire black population waits for its emancipation (and its rewards for taking part in the Boer War, the majority of them supporting the British).

Say what! It’s not all about the hatred of the British, Concentration Camps, forced to fight for the British against friendly brethren Germans …. Its about the … blacks!

What you smoking? Yup, I’m afraid there it is, commentators at the time like Sampson were pointing to issues of race – the internal politics at play, not just the geo-politics. To set up the ‘race’ argument Sampson goes in depth into each of the leaders of the revolt by way of outlining their character and disposition to race.

Beyers is described as a very religious man, however he was inordinately vain of his personal appearance (which looking at his pandering to his hair, a monumentally stylised moustache and his disposition to fine and dandy clothing sounds about correct), and regarded as megalomaniac by the man in the street, in fact they “used a more expressive term” to describe him – one not for polite publication. Beyers after the Boer War took to entertaining “veldt Boers” coming in for ‘indabas’ in Pretoria and he earned a reputation as a Anglophobe with a “with a particularly venomous tongue.”3

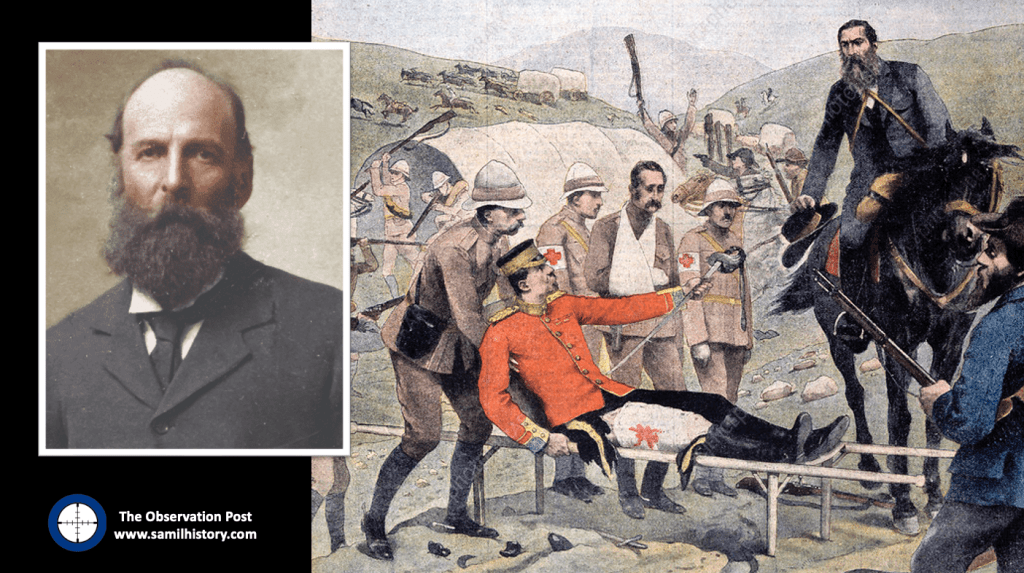

De Wet is described by Sampson as a different sort of person to Beyers. De Wet too is religious but religion does not dictate his actions – politics does. He is angry with Botha and Smuts for removing Hertzog from cabinet. As a Free Stater he is unhappy with these “Transvaal Boers” entertaining the British request of ‘colour blind qualification franchise’ (which is in fact a Boer War 2 peace treaty pre-requisite). It’s here that we see a common thread in many of the rebel leaders, sheer racism and a desire to maintain an white Afrikaner led oligarchy in South Africa with no rights whatsoever to anyone of colour.

Sampson places De Wet into what he calls a “Old School” Boer whose:

“Abiding fear always has been that British government in South Africa meant that the ascendancy of the whites over the blacks would cease, and one day the kaffirs would be permitted to be on an equality with the whites.”4

Sampson cites this fear of Black ascendancy over Whites as a primary rally call for the Boer Republican armies during the South Africa War (1899-1902). He goes on to outline De Wet deep hatred for Black people as his primary motivator for going into the 1914 Rebellion, he writes:

“De Wet always has treated kaffirs with severity, regarding them as little better than animals, whom he believed he ought to have the right to thrash as he would a dog, it only needed a fine for ill-treating a native to bring on a raging brainstorm that drove him headlong into the maelstrom of rebellion. To fine him, De Wet, was the greatest outrage conceivable, and clear proof that the time had come to strike a blow for freedom!”5

This sentiment and motive for De Wet going into Rebellion as outlined by Sampson is borne out by Jan Smuts, who later uses the fine De Wet gets for assaulting the said black man with a shambok – which was 5 shillings. In broad media, Smuts belittles both De Wet and his purposes behind the revolt by calling it the “5 Shilling Rebellion”.

Christiaan de Wet would go on to say of the Colour Blind Qualified Franchise policy and the fact its still upheld in the Cape Providence:

“The ungodly policy of Botha has gone on long enough, and the South African Dutch are going to stand as one man to crush this unholy scandal.”6

Manie Maritz is also described within his deep-seated racism – he is noted as a man of:

“Enormous strength, inordinate vanity, little education, and the one, perhaps, of all the rebels most open to the influence of German gold.”7

Jopie Fourie is described by Sampson as a religious mans and a very pleasant man – however his Anglophobia seemed to have grown on him like a disease starting with his resentment because of a permanent limp, caused by a bullet wound in the knee during The South African War (1899-1902), and this:

“intensified the bitterness to one who had been a fine footballer and athlete”.8

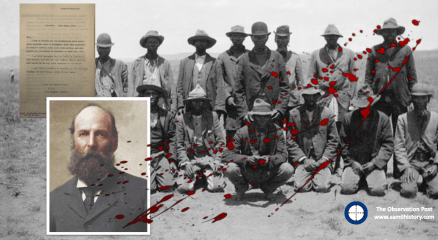

What follows in ‘The capture of De Wet’ is the ‘Black’ part of the 1914 Afrikaner Revolt, the declaration from Maritz stating that any blacks standing in the way of the rebels will simply be executed. His declaration Maritz states:

“Several cases are known where the enemy has armed natives and coloured people to fight against us, and as this tends to arouse contempt among the black nations for the white, an emphatic warning is issued that all coloured people and natives who are captured with arms, as well as their officers, will be made to pay the penalty with their lives.”9

The killing of Allan William King, the Native representative by Fourie’s Commando. The declaration by the said ‘Natives’ to avenge King and enter the war on their own terms and wipe Fourie’s Commando out by themselves – they are held back by King’s wife who pleads with them for restraint. Sampson notes of ‘rise’ of the ‘Natives’ to avenge King:

‘The natives of the district were almost crazy with rage at the loss of their ” Father,” as they deemed Allan King …. They sent a deputation of chiefs and headmen into Pretoria to see the wife of their dead “inkosi,” to assure her of their love for him … and said to her “Say the word, and we will kill every one of these bad men, and also their wives and children !”10

But Mrs. King shook her head and forbade them to raise a finger, for well she realized the horrors that might follow if once the natives commenced reprisals. The rebels have to thank the wife of the man they so unfairly shot that all their throats were not cut that night, their wives and children assegaied, and their homes given to the flames.’11

The position of Sol Plaatje as to the revolt and Native rights also becomes important. So too is the lambasting of Christiaan de Wet and his martial abilities – and even his influence, his reputation shattered.

Not only Sampson, General Jan Smuts was highly critical of Christiaan de Wet’s fighting abilities and strategic acumen. His son Captain Jannie Smuts would record his father’s disposition, it gives an interesting insight on de Wet and his disposition to making irresponsible strategic and operational decisions – driven instead by emotion and irrational ideals, here it is:

“It might here be noted that there was considerable divergence of opinion amongst the (1914) rebel leaders on their course of action. Beyers wanted a relatively passive though armed form of resistance – the type that came to be known as a “coup” in the Second World War. He was against civil war. De Wet, more fiery and impetuous, was for vigorous action and pushing through to connect up with Maritz. In his zeal he forgot that he was poorly armed, had no field guns, and was short of ammunition. He also failed to reckon with the mobility afforded the Government by the much-extended railway system, or the advent of the petrol driven motor-car”.12

In other words, as a pivot leader of the Boer Revolt of 1914, Christiaan de Wet was flying by the seat of his pants (a trait not uncommon with his approach to the South Africa War 1899-1902) – completely unprepared he was bent on full sedition and revolt to reinstate ZAR republicanism, an oligarchy run on a Boer paramountcy and its severe laws of racial exclusivity and repression throughout the South African Union – paying little regard to the strategic ramifications, operational requirements or even modern military advancements, completely underestimating his enemy, just blindly pursuing his “impetuous” pipe dream.

Yup, its a WHOLE different view of the Afrikaner revolt and its not one you get from your Afrikaner Christian Nationalist education and its certainly not one you get from modern day Afrikaner historians. They have been telling you it’s all about ‘the British’ for decades … and meanwhile, the one and only ‘English’ historian to write on the matter at the time is simply dismissed, completely bypassed – his work simply discarded as ‘jingoism’ – so not relevant.

One thing is a truism, and its true of many Boer War or Boer Revolt books and academic papers directed to Afrikaner consumers in the past, is that the works tend to cater to a specific Afrikaner ‘Volksgeist’, one which has little resonance outside of white Afrikaans culture. These works tend to highlight the ‘whiteness’ of the conflict, and focus primarily on Afrikaner cultural dynamics. One hopes that any new book on the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion brings something new to the table, one in which the ‘Black’ and the ‘English’ part of the 1914 Rebellion is fully appraised, researched and understood, an in-depth appraisal of race politics of the time, the role played by Black Africans, Coloureds, Indian and even English speaking white South Africans in the revolt i.e. the majority of South Africans – their political representations, reactions and aspirations – what they were “fighting for”, their “freedom” in effect.

Without this, the majority of South Africans will find themselves, once again, as by-standers to this history and they will pay no attention to it whatsoever. The ‘new’ work having no real resonance to modern South African society – just a re-packaged, re-marketed regurgitation of the old white Afrikaner Nationalist debates targeted at a fresh new Afrikaner audience for a little commercial gain.

As a very reputed historian – Dr. Damian P. O’Connor, also pointed out recently, the problem with removing or brushing over sources, especially written accounts such as this one from the period, on the basis of ‘jingoism’ or just ‘not conveniently fitting’ into a Afrikaner nationalist political narrative or even an Afrikaner author’s bias brought about by years of nationalist identity politics and socialisation … is that once we’ve dismissed a first hand written account we are left with nothing, just pure hearsay and verbal tradition .. empty space in effect, and into that ‘empty space’ anyone can write anything they like, we can just make it up. It becomes revisionist history – pure ‘gone with the wind’ romantic drivel.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References:

- The Capture of De Wet. The South African Rebellion 1914 – Sampson, Philip J. Published Edward Arnold, London. 1915

- JC Smuts. Jan Christian Smuts by his son J.C. Smuts. Heinemann & Cassell Publisher, 1952.

Footnotes

- Smuts, Smuts by his son, 239 ↩︎

- Smuts, Smuts by his son, 240 ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, 5 ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, vii ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, vii ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, 148 ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, vii ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, vii ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, 252 ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, 191 – 193 ↩︎

- Sampson, Capture of De Wet, 193 ↩︎

- Smuts, Smuts by his son, 234 ↩︎