Torch Commando Series – Part 3

Forging a ‘Steel’ Commando

In researching The Torch Commando, quite often the word ‘Steel Commando’ comes in. Now, what exactly was The Steel Commando – some have incorrectly ventured that it was an equivalent to the ‘Greyshirts’ i.e. the strongmen enforcers within a political party – this is not the case, in fact the Steel Commando has an interesting origin, both in history and name. Central to the Steel Commando is the idea of winning hearts and minds – in the Steel Commando’s case it’s very much the Afrikaner ‘heart and mind’ they are after.

So, quick re-cap to my favourite area of research – The Torch Commando, a post-World War 2 mass-movement of ‘white’ ex-military servicemen, a political pressure group against the accent of the National Party into power in 1948 and their first submissions of Grand Apartheid legislation from 1950. It was not an insignificant movement, at its zenith The Torch Commando boasted 250,000 paid up members and as inconvenient truth goes, when it was formed it becomes the first mass anti-Apartheid protest movement, starting in April 1951, its origin pre-dates the African National Congress’ (ANC) ‘Defiance Campaign’ – which is their first mass mobilised protest against Apartheid and started in June 1952. The part that also does not sit with the current ‘struggle’ ANC rhetoric, the Torch Commando was almost exclusively ‘white’.

The dynamics behind the National Party’s ascent to power without a majority vote in 1948 have been vastly researched but suffice it to say that for returning War Veterans from WW2, fighting against Nazism, the advent of a political party with numerous leaders who had been directly and/or indirectly flirting with Nazism during the war as a net result of organisations like the Ox Wagon Sentinel (Ossewabrandwag) and other Neo Nazi factions merging with The National Party was an abhorrent idea and an insult to the sacrifice of their comrades in arms.

The outrage to this and the implementation of the first Acts and Bills that would become ‘Apartheid’ would result in a merger of war veteran members of the Springbok Legion veteran’s association and war veterans predominant in the United Party’s political structures in April 1951 – the ‘War Veteran’s Action Committee WVAC (the WVAC was to eventually evolve into The Torch Commando) under the leadership of the charismatic war-time fighter ace – Adolph Gysbert Malan, DSO & Bar, DFC & Bar, better known as Sailor Malan, a veteran with Afrikaans heritage. The WVAC is careful to balance its demography to reflect the views of both Afrikaners and English-speaking whites who had participated in all South Africa’s Wars and it is balanced 50/50 Afrikaans/English in its make-up. Now, the question is why did they have to do that – why the focus?

The answer to this question has its origins in the way the South African Union Defence Force has been constructed and the way the South African public voting bloc – those eligible to vote is constructed and its dynamics. So, let’s look at the Defence Force.

The Union Defence Force

The South African Union Defence Force (UDF) from its origins in 1914 was carefully constructed by Jan Smuts to have an Afrikaner and English ratio of 60% Afrikaners and 40% English speaking whites, a proportional representation of the actual demographic of South Africa – at first – for World War 1 starting in 1914, the Afrikaners primarily exist in the ‘Rifle Associations’ which are effectively the old Boer Republic’s Commandos and the English speaking South Africans exist in the ACF ‘Active Citizen Force’ Regiments – like the Royal Natal Carbineers, South African Light Horse and Durban Light Infantry, most of whom have origin in the old Natal and Cape Colony ‘Colonial Forces’ during the Boer War.

By the time the Second World War swings around in 1939 the UDF is a slightly different beast, but it still has its 60/40 ratio of Afrikaans to English, with Afrikaners in the majority, Jan Smuts calls out for volunteers, joining the Union Defence Force from the adult ‘white’ base of approximately 1,000,000 people in 1940 is 211,000 whites (with 120,000 Black, Coloured and Indian service personnel in addition).

It’s an extraordinary response to a call-up to military service on voluntary lines, South Africa is one of the few participating countries in the Allied war effort not to implement conscription and as a population ratio – nearly a quarter of all white South African adults actively seeking service.

Contrary to the myth asserted by the old National Party. The idea that 2nd World War was primarily fought by the ‘English’ white South Africans who had an affinity to Britain, Smuts had somehow turned ‘British’ and true ‘Afrikaners’ sat out the war as members of organisations like the Ossewabrandwag and the National Party either desiring neutrality due to a universal disgust with all things British (a hang-over from the Boer War) or in active support of Germany. However, this is a myth – it’s simply untrue.

The truth is that Smuts’ call had as much resonance with white Afrikaners as it did with white ‘English’ – of the white population volunteering for service, the pool reflects the national demographic split of the 60/40. So, approximately 127,000 Afrikaners and 84,000 ‘English’ – the Afrikaners are still the majority. Smuts’ call is simply broadly accepted by both white communities and extremely popular – fact, this is again where Economic History starts to tear gaping holes into ‘Political’ history narratives.

The voting bloc

Now let’s look at the white and coloured voting bloc and its dynamics. After the war ends in 1945, the National Party rather surprisingly wins the General Election in 1948, NOT by a majority, it’s a minority government winning on ‘constitutional’ grounds (number of seats) and NOT a popular one.

Of the 1,000,000-adult voters in 1948 (the full actual vote count is 1,065,971 voters) – more or less as numbers go – 550,000 voted against Apartheid (for Jan Smuts’ United Party and their more liberal parties – The Labour Party etc.) as opposed to 450,000 who voted in favour of Apartheid (for the Afrikaner Nationalists – the re-united National Party and Afrikaner Party coalition). The ‘coloured’ vote – the Cape Franchise has within it approximately 50,000 voters and these have almost exclusively gone with the United Party and its partners (one of the National Party’s intended aims is to remove their franchise), so we can deduce that about 500,000 whites and 50,000 coloureds have voted against Apartheid.

This alone qualifies an inconvenient truth. So much for the rather incorrect modern argument put forward by the ANC and other Black Nationalists that ‘white’ people in South Africa as a coherent whole voted to maintain their ‘privilege’ and are therefore responsible for Apartheid and the renumeration of black society hobbled by it. That agreement is simply not true – the majority of whites did not vote for Apartheid – the proof is in the statistics.

Albeit not a majority, clearly some Afrikaner ex-servicemen in the military veteran ‘service’ voting bloc have been moved to support Afrikaner Nationalism – prior to the election the National Party did a large degree of “swart gevaar” (Black Danger) fear mongering around Jan Smuts’ declaration that “segregation had fallen on evil days” and this has resonated with some Afrikaner servicemen, disillusioned in their discharge from the UDF, feeling vulnerable and seeking fundamental reforms within an Afrikaner hegemony.

What the War Veterans Action Committee (WVAC) aims to do is woo these white Afrikaans ex-servicemen voters back to either the United Party or the Labour Party. They also want to encourage ex-Afrikaner servicemen from Boer War 2 and World War 1 to join hands with the World War 2 veterans as a show of unified strength that many in Afrikaans community are simply not in favour of Apartheid – even some of the old highly regarded and much-loved Republican Boer War veterans who are still around.

The opening shots

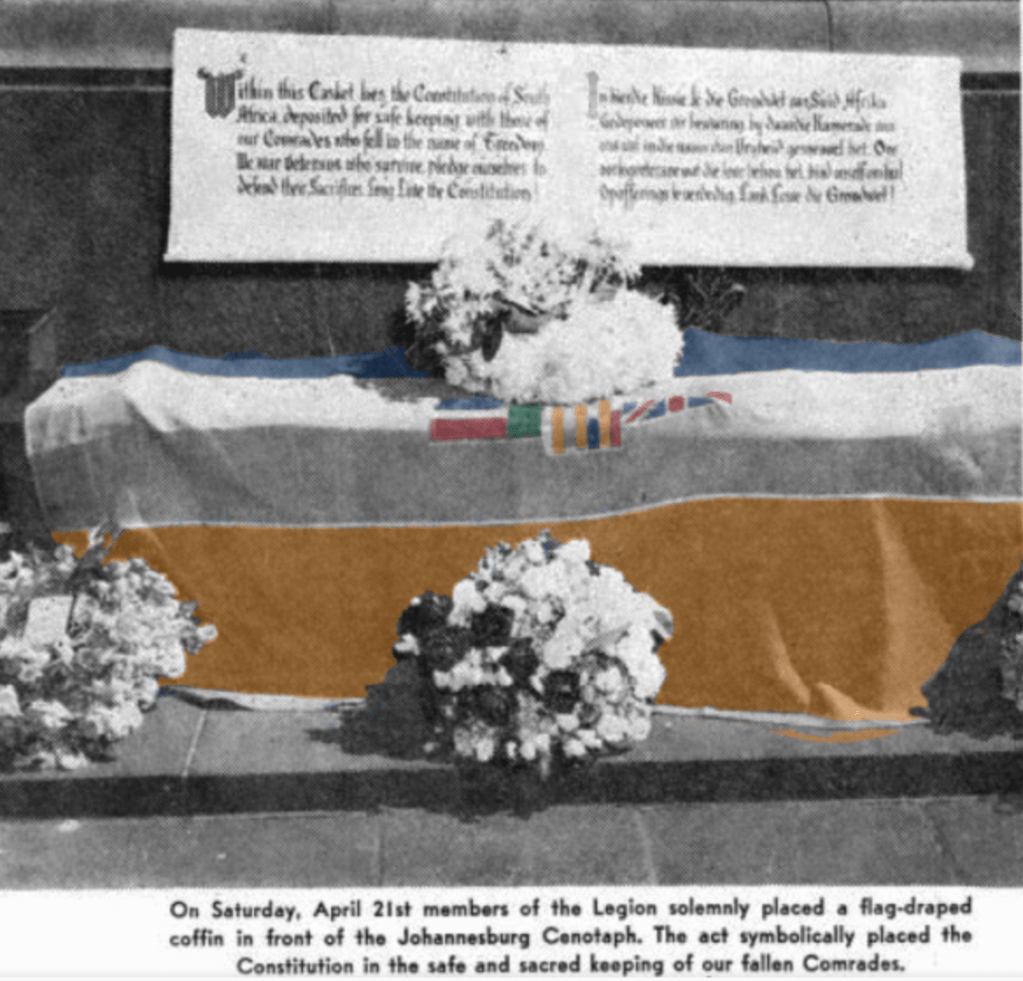

The War Veterans Action Committee (WVAC) kicked off their mission with a protest at the Johannesburg Cenotaph on 21st April 1951 during a commemoration service – laying a coffin draped in the national flag as a symbol to depict the death of the Constitution.

So, after the Cenotaph parade, the War Veterans Action Committee (WVAC) elected to ‘ramp-up’ their resistance and hold bigger protests using military precision and planning to activate the significant ‘ex-services’ vote and its supporters, so as to bring about regime change through the ballot box.

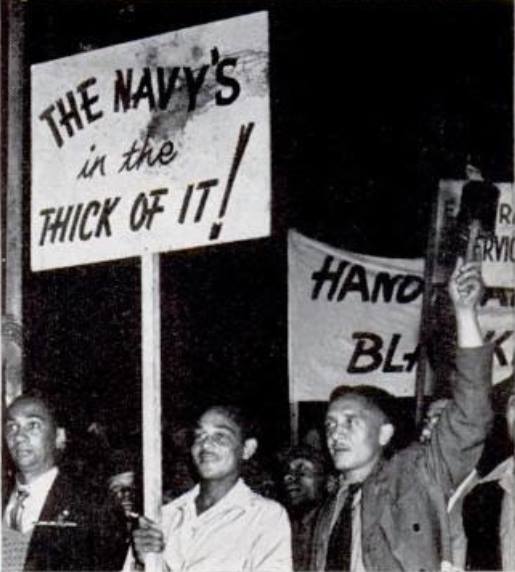

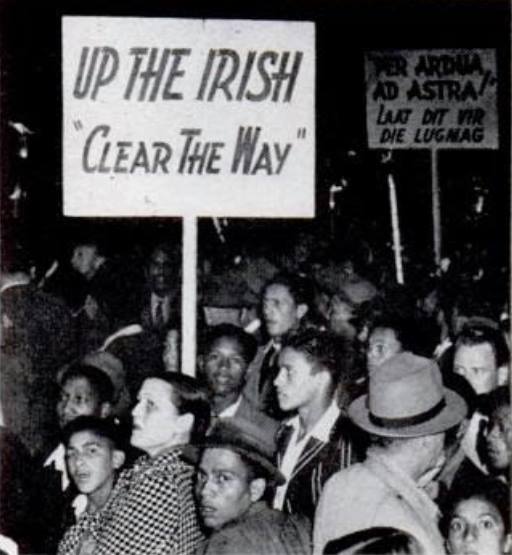

On the 4th May 1951, two political rallies were held, one Durban attracted 6,000 people and a second larger one 25,000 people strong, attended by Sailor Malan was held in Johannesburg. The protest marches were held at night and flaming torches were carried for effect – the Torches became symbols of ‘hope’, ‘freedom’ and ‘light’ – and would ultimately be the trademark of the movement with carriers known as “Torch-men”. The proposed idea to the audience was to initiate a ‘crusade’ against the Afrikaner Nationalists in the same spirit as their ‘crusade’ against Hitler and for the same reasons.

The Johannesburg rally saw more than 5,000 veterans ‘on-parade’ carrying Torches march from Noord Street near the railway station to the Johannesburg City Hall. They we joined by approximately 15,000 civilians as they gathered outside the City Hall. Sailor Malan was to outline this intention to crusade when he referred to the ideals for which the Second World War was fought:

“The strength of this gathering is evidence that the men and women who fought in the war for freedom still cherish what they fought for. We are determined not to be denied the fruits of that victory.”

Sailor Malan

At these meetings on 4th May the following resolutions were taken and unanimously agreed:

- We ex-servicemen and women and other citizens assembled here protest in the strongest possible terms against the action of the present government in proposing to violate the spirit of the Constitution.

- We solemnly pledge ourselves to take every constitutional step in the interests of our country to enforce an immediate General Election.

- We call on other ex-servicemen and women, ex-service organisations and democratic South Africans to pledge themselves to this cause.

- We resolve that the foregoing resolutions be forwarded to the Prime Minister and the leaders of the other political parties.

A further meeting was held in Port Elizabeth, attended by 5,000 people, at this meeting the following resolution was outlined;

“This meeting condemns the present government for violating the liberties for which the wars of 1914 – 1918 and 1939 – 1945 were fought and for disregarding the moral undertakings enshrined in our Constitution. We pledge ourselves to continue the struggle to ensure we and our children live in true democracy.”

A manifesto would be released on the 13th May and the war veterans resolved to form a ‘Steel Commando’ to send these four resolutions of protest directly to Parliament in Cape Town. A jeep convoy was put together with precision from all major metropoles to convene in Cape Town on the 28th May 1951. But why the term “Steel Commando” – what resonance would that have and what were the objects of using this concept? Here again – this has a distinctive Afrikaner heritage and appeal. So, here’s some background.

The Steel Commando – an Afrikaner root

Just prior to World War 2, the Broederbond under the directive of its Chairman, Henning Klopper conceived a travelling carnival to celebrate the 100-year anniversary of the Great Trek – it was known as the 1938 Great Trek Centenary its purpose was the establishment of a unified Afrikaner identity under a white ‘Voortrekker’ hegemony – the underpinning of Afrikanerdom with a Christian Nationalism ideology. The long and short, this travelling caravan of Voortrekker wagons traversing to the most rural parts of South Africa on their way to the Blood River battle-ground and the future site of the Voortrekker monument outside Pretoria to lay its cornerstone … it was a massive success, resonating with Afrikaners country-wide and bringing together the impossible – the Boer Afrikaner and the Cape Afrikaner under a ‘white’ Voortrekker’s “path for South Africa” banner.

Two years later, during World War 2, the recruitment of white Afrikaners to volunteer for war service became paramount to Union’s Defence Force wartime objectives. Dr Ernie Malherbe and a group of academics, notably Alfred Hoernle and Leo Marquard, persuaded General Smuts to set up, under Malherbe, a corps of information officers to counter subversion in the armed forces generated by the likes of the Ossewabrandwag and the Broederbond and to stimulate the Afrikaner troops and potential white Afrikaner recruits to consider what they were actually fighting for.

Colonel Malherbe would take a leaf out of the Broederbond’s 1938 Centenary Trek used to ‘unify’ the Afrikaner – a round the country travelling carnival covering just about every town and village in the remotest areas. Only this time Colonel Malherbe intended that the travelling carnival ‘unify’ the Afrikaner behind Smuts’ call to arms to fight with Britain and France on the side of the Allies. He would use armoured cars instead of ox-wagons and his message was almost diametrically opposite to that of the Broederbonds’.

Colonel Malherbe would call his countrywide travelling carnival – The Steel Commando, added to this would be a propaganda and recruitment pamphlet dropping campaign from SAAF aircraft called the Air Commando. The Steel Commando would consist of vehicle to carry a full military band, various armoured cars and a truck converted into a mobile recruitment station.

Critical to the Steel Commando would be a contingent of old Republican Boer War veterans (South African War 1899-1902) to give it a sense of ‘Afrikanerdom’ and ‘duty’ to South Africa. The term ‘Commando’ would be given to the convoy – solely because it resonated with old Republics ‘Kommandos’ of the Boer war and as a result had Afrikaner appeal.

This convoy would enter small rural and farming towns with the fanfare of the marching band ahead of it, flanked by the Boer War Republican veterans and the recruiting station behind. Was it effective in capturing the Afrikaner hearts and minds as the Centenary Trek had been? The truthful answer is – yes. In all the South African standing forces in WW2, Malherbe was satisfied in the objects of The Steel Commando – the single majority ethnic group in the South African Union’s Defence Force during World War 2 were white Afrikaners (126,600 of them).

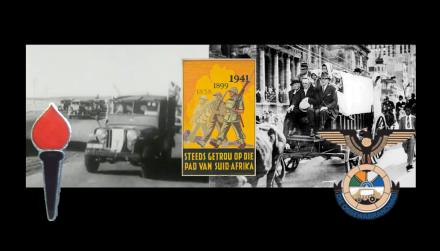

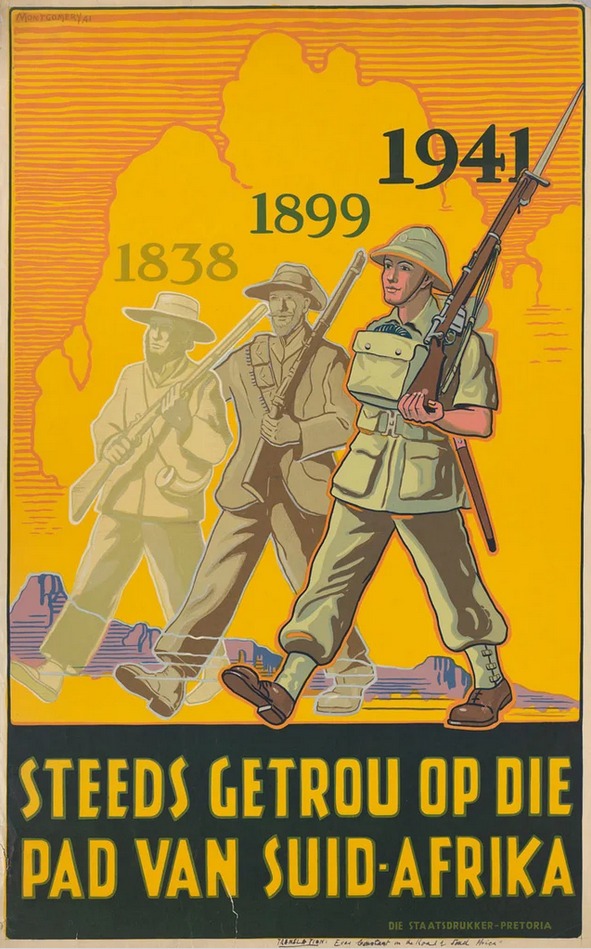

Images: World War 2 recruitment posters targeted at white Afrikaners – note the poster drawing on the ‘the road to South Africa’ commencing from The Battle of Blood River to the Boer War Commandos to the South African Union Army – the title “Still loyal to the path of South Africa” is a direct play on the 1938 Centennial Trek which the Broederbond pitched as “Die Pad van Suid-Afrika,” a symbolic ‘path’ to South Africa’s nationhood taken by the Voortrekkers. This poster attests that joining the Smuts appeal to war is the true path to nationhood.

To see the effect of a Steel Commando parade, this video outlines one addressed by Smuts as a demonstration of the achievements of recruitment is very telling – note the extensive use of Boer Commando veterans.

What the Steel Commando and Colonel Malherbe’s recruitment drive also did was literally split the Afrikaner ‘hearts and minds’ in two, one half supporting the National Party’s call to neutrality or the Ossewabrandwag’s call to directly support Nazi Germany – and the other half of white ‘Afrikanerdom’ – supporting the ideals of Union between English and Afrikaans, General Smuts’ policies and the Allied war against Nazi Germany.

The Steel Commando … repurposed

So, to whip up support for their Anti-Apartheid cause, and how to whip up the planned mega-torchlight rally in Cape Town to hand over the demands? The War Veterans Action Committee took a leaf out of Colonel Malherbe’s Union Defence Force ‘Steel Commando’ recruitment drive. They would not even change the name, the WVAC’s ‘Steel Commando’ would be run along the same lines with military precision. All around the country from far flung places vehicles would converge with the Steel Commando and the Commando itself would drive through multiple towns and villages whipping up publicity and support.

To balance the authority of the Steel Commando been both for ‘English’ and ‘Afrikaners’ alike and give it a high appeal, leading the ‘Steel Commando’ convoy to Cape Town a big hitting Afrikaner war hero – Kommandant Dolf de la Rey, a South African War (1899-1902) i.e. Boer War 2 veteran of high standing in the old Republican Forces of the Boer War. Part of Commandant Dolf de la Rey’s legacy was that he was reputed to have been involved in the actions around Ladysmith which resulted in the capture of Winston Churchill. Kommandant de la Rey was also affectionally given the term ‘Oom’ by the publicity machine to conjure up respect from the Afrikaner community.

The ‘Steel Commando’ convoy gathered media attention and grew in size as it converged on Cape Town on the 28th May, a crowd of 4,000 greeted it as it converged in Somerset West before heading to Cape Town that evening.

This is a rare News reel of The Steel Commando drive – Note Kmdt Dolf de la Rey and the Republican Boer War veterans with him.

One newspaper correspondent wrote of it:

“Cape Town staged a fantastic welcome for Kmdt de la Rey and Group Captain Malan, he related the enthusiasm of the crowd to the same that liberation armies received in Europe.”

The Johannesburg Star said:

“The Commando formed the most democratic contingent ever to march together in the Union. Civil servants found themselves alongside the coloured men who swept the streets they were marching so proudly upon. In the front jeep rode Oom Dolf de la Rey, a white-haired old Boer of seventy-four, who looked so startlingly like the late General Jan Smuts that people looked twice at him and then cheered wildly. Oom (Uncle Dolf) was the man who, as a young burgher on commando fifty years before, had captured Winston Churchill, then a war correspondent with the Imperial forces in South Africa. In the second jeep stood a younger man with tousled brown hair, his hazel eyes cold and angry, the man who had been the most famed fighter pilot in all the RAF — Adolph Gysbert Malan, known all over the world as Sailor. He was the real hero of the hour. The people tried to mob him. Men and women, white as well as brown, crowded round his jeep and stretched out their hands to touch him”.

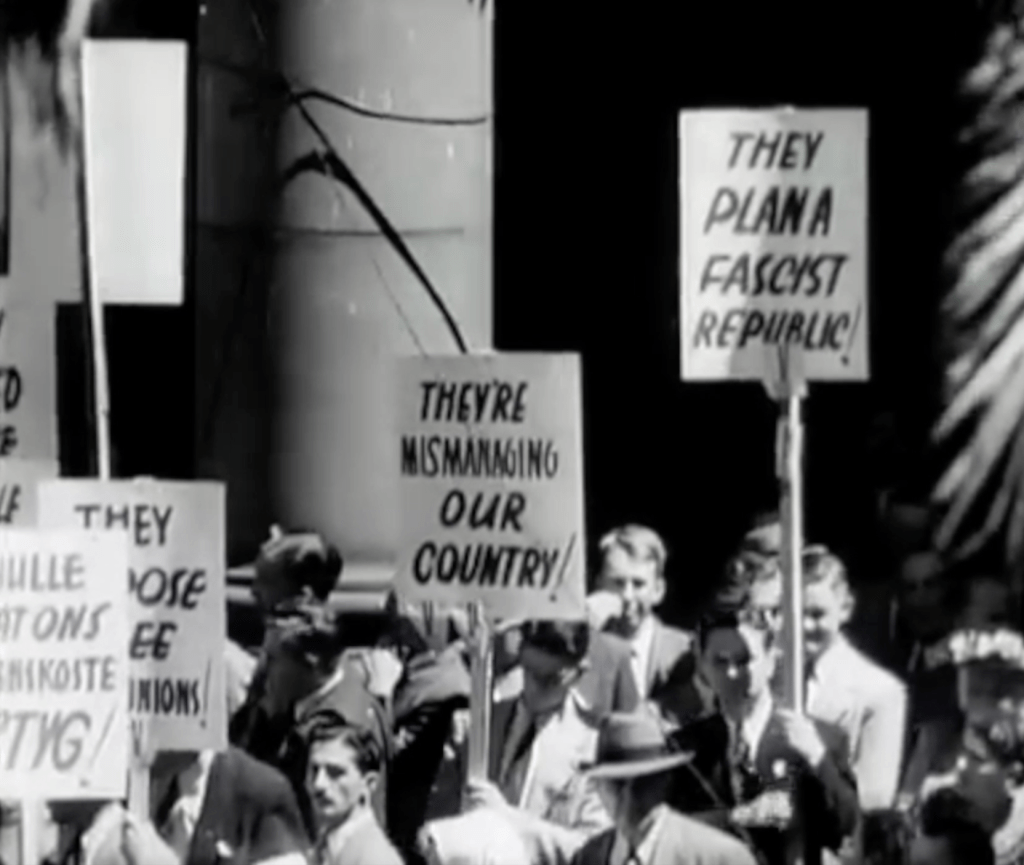

In Cape Town, the Steel Commando arrived to a packed crowd of protesters on The Grand Parade outside the City Hall of between 55,000 to 65,000 people – consisting of whites and coloureds, supporters and veterans alike (veterans were estimated at 10,000). Many holding burning torches as had now become the trademark of the movement. Spooked by it all the National Party were convinced that a military coup was on and as a precautionary measure placed manned machine gun positions around the rooftop of the nearby Houses of Parliament.

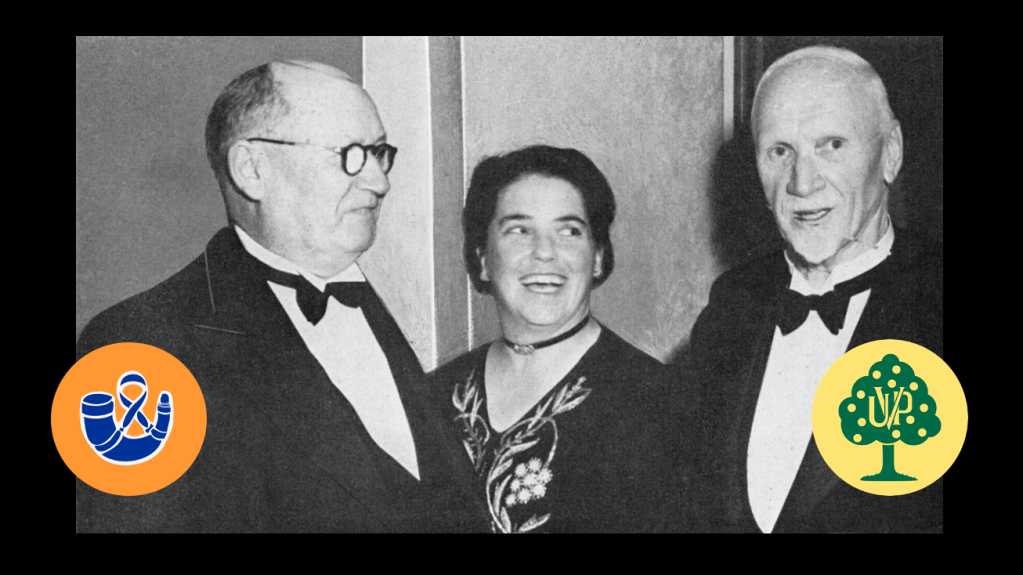

Sailor Malan was literally carried on shoulders by cheering crowds to give his speech. Joined by Dolf de la Rey and even future Afrikaner anti-apartheid activist and fellow war veteran Mattheus Uys Krige as well as the English speaking South African war-time soprano and heroine who led them in song – Perla Gibson. In Sailor Malan’s speech to the crowd famously accused the national party government at this rally of;

“Depriving us of our freedom, with a fascist arrogance that we have not experienced since Hitler and Mussolini met their fate”.

Sailor Malan

During the rally in Cape Town, Dolf de la Rey took the microphone and laid into the National Party, as a respected Boer War vet he pulled no punches. Also, this is an inconvenient truth, Dolf de la Rey headed up an entire contingent of Boer War, Boer Republican Afrikaner veterans, on the Steel Commando – all of whom did not feel that Apartheid as outlined by the National Party was reflective of them as Afrikaners.

After the speeches formalities of the protest were closed, a group of mainly ‘coloured’ protestors and some ‘torch-men’ veterans rose-up in violent resistance and surged up the hill to the Houses of Parliament and clashed with the Police, the resultant violence left about 160 people injured and damaged the windows and railings of the ‘Groote Kerk.’

Now that there had been a clash with Police, the Afrikaner changed their tune and stance towards the War Veterans accusing them of starting violent riots and insurrection – threating a military coup. Johannes ‘Hans’ Strydom (National Party Minister and future NP Prime Minister) finally warned the war veterans that he would use the South African security forces against;

“Those who are playing with fire and speaking of civil war and rebellion”.

Hans Strydom

Although the violence was dismissed by the War Veterans as not being of their making and unplanned, the Nationalists fear of violent military insurrection was not unfounded, both John Lang and Jock Isacowitz would later admit that the intention of many of the ‘torch-men’ on protest that day was always to surge on to Parliament and “throw out the Nationalists.”

The Nationalists continued to position the Torch as a national threat attempting a violent overthrow. This statement was equally quickly rebutted as nothing but shameful rhetoric by the National Party’s official opposition – the United Party. So, the Nationalists went further and targeted the personalities of Malan and de la Rey, bottom line is they did not want young Afrikaners influenced by these two national war heroes.

Sailor Malan was an easy target, he was the product of a Afrikaans father and English mother – he quickly became “the King’s poodle” and “an Afrikaner of a different kind” – not welcome in the Afrikaner laager. But, problem with ‘Oom Dolf’, here was a Afrikaner Boer War hero pure and applied, beyond the National Party’s criticism and reproach, so what did they do? They quietly dismissed him on his ‘Oom’ status, a senile old man, positioning him as somehow irrelevant, a patronising .. Ja Oom!

Formation of the Torch Commando

On the back of the successful widespread support of ‘The Steel Commando’ and determined to continue the fight to effect regime change, the ‘The Torch Commando’ took shape and it took to a more formalized structure of a central command with devolved authorities in the various regions of South Africa, using military discipline, military styled planning and lines of communication to activate.

Officially launching as the Torch Commando, Group Captain Sailor Malan was elected National President of the Torch, Major Louis Kane-Berman was elected National Chairman. To keep with the Afrikaner appeal and skew, the appointed Patron-in-Chief for the Torch Commando was Nicolaas Jacobus de Wet, the former Chief Justice of South Africa. Finally, the National Director was Major Ralph Parrott, a ‘hero’ of the Battle of Tobruk from the Transvaal Scottish who received the Military Cross for bravery.

The Torch Commando is yet another demonstration of the rich tapestry of Afrikaner war veterans not in support of Apartheid – Afrikaners either joining or supporting the likes of Dolf de la Rey and Adolph ‘Sailor’ Malan in The Torch Commando would include many heavy-weight Afrikaner hitters, people like Mattheus Uys Krige – 2nd World War, correspondent and POW, poet and novelist, Torch Commando member and life-long anti-Apartheid campaigner. General Kenneth Reid van der Spuy – 1st World War and 2nd World War veteran and regional leader in the Torch Commando. General George Brink – 1st World War and 2nd World War veteran and a regional leader in the Torch Commando. Major Jacob Pretorius – 2nd World War and leader in the Torch Commando. Pvt Pieter Beyleveld – 2nd World War veteran, Labour Party and Springbok Legion, Torch Commando activist and life-long anti-apartheid campaigner.

Other Afrikaners would support the Torch, people like Lieutenant (Dr) Jan Steytler – 2nd World War veteran founder of the Progressive Party and Liberal politician. Captain (Sir) De-villiers Graaff – 2nd World War veteran, opposition United Party leader and New Republic Party founder, life-long anti-apartheid campaigner and supporter of the Torch Commando (in fact he hosted Sailor Malan on his ‘Steel Commando’ protest drive). Lt Harold Strachan – 2nd World War veteran, member of the Liberal Party, Congress of Democrats and Communist Party (he also became a founding member of MK). Major Pieter van der Byl – 1st World War veteran, South African Party, United Party and anti-Apartheid opposition stalwart and finally Colonel Ernst Gideon Malherbe – 2nd World War veteran, educator and famous South African academic.

The Commando would grow from strength to strength over the next couple of years, reaching a zenith of 250,000 members – nearly a quarter of the voting bloc and a significant threat to the National Party – do look out for the next Observation Post on The Torch Commando which will cover its rise.

In Conclusion

It is a very incorrect assumption to go with the old National Party rhetoric that they represented the interests of the majority of whites in South Africa, and to be a true Afrikaner you had to be an Afrikaner Nationalist. It is also very incorrect to connect Afrikaner identity to the white Voortrekker hegemony as devised by the Broederbond in their ‘Christian Nationalism’ construct in 1938, and most importantly – it is very incorrect to believe that Afrikaners are a homogeneous group with a homogeneous identity and as a group are all collectively responsible for Apartheid from 1948. The Torch Commando and the nature of Afrikanerdom prior to the National Party coming into power in 1948 is proof positive, that the majority of whites and a significant part of the Afrikaner nation were simply not on board with the idea of Apartheid.

Editors Note:

As this research field includes the ‘racial constructs’ of Krugerism leading up and including Boer War 2 (1899-1902) and as an ideology and its role in establishing The National Party (and the onset of ‘Apartheid’) from 1914. In addition it also includes the ‘Nazification of the Afrikaner Right’ from 1936 and the political awakening of returning Afrikaner World War 2 veterans from 1950 because of it – the Observation Post often gets comments on both the blog and social media that it is somehow biased to the ‘British’ and ‘Afrikaner bashing’ or ‘Boer bashing’ – it is neither.

What the Observation Post elects to highlight are the actual demographics, the economic history and not the political history peddled for political gain. It elects to highlight the progressive political deeds of Afrikaner military heroes like Dolf de la Rey and Sailor Malan, and all the Afrikaner military men in the Torch Commando whose legacies were buried by the Afrikaner Nationalists for decades and men whose truth must now ‘out’.

Given the current political assault on Afrikanerdom in modern South Africa this is key to understanding Afrikanerdom in its proper historical context – sans the National Party and now the African National Congress’ interpretation of it.

The Torch Commando – next instalment

What follows next is called ‘The Rise and Fall of the Torch Commando’ – please click through to this Observation Post link which covers in this phase depth.

The Torch Commando – Part 4, The ‘Rise and Fall’ of the Torch Commando

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References:

The Torch Commando & The Politics of White Opposition. South Africa 1951-1953, a Seminar Paper submission to Wits University – 1976 by Michael Fridjhon.

The South African Parliamentary Opposition 1948 – 1953, a Doctorate submission to Natal University – 1989 by William Barry White.

The influence of Second World War military service on prominent White South African veterans in opposition politics 1939 – 1961. A Masters submission to Stellenbosch University – 2021 by Graeme Wesley Plint

The Rise and Fall of The Torch Commando – Politicsweb 2018 by John Kane-Berman

The White Armed Struggle against Apartheid – a Seminar Paper submission to The South African Military History Society – 10th Oct 2019 by Peter Dickens

Sailor Malan fights his greatest Battle: Albert Flick 1952.

Sailor Malan – Oliver Walker 1953.

You-tube AP video footage of The Torch Commando.

Lazerson, Whites in the Struggle Against Apartheid.

Neil Roos. Ordinary Springboks: White Servicemen and Social Justice in South Africa, 1939-1961.

“Not for ourselves” – a history of the South African Legion by Arthur Blake.

Pro-Nazi Subversion in South Africa, 1939-1941: By Patrick J. Furlong.

The Rise of the South African Reich: 1964: By Brian Bunting

The White Tribe of Africa: 1981: By David Harrison

National Socialism and Nazism in South Africa: The case of L.T. Weichardt and his Greyshirt movements, 1933-1946: By Werner Bouwer

The Final Prize: The Broederbond by Norman Levy: South African History On-line (SAHO) War and the formation of Afrikaner nationalism: By Anne Samson: Great War in Africa Association

Colourised photo of Sailor Malan – thanks to Photos Redux

Related Work

This work falls part of preparation work for a seminar on Sailor Malan called ‘I fear no man’ by Dr Yvonne Malan, scheduled for 16th September 2023 in Kimberley, here’s the link “I Fear No Man” – Sailor Malan Memorial Lecture

The Torch Commando Series

The Smoking Gun of the White Struggle against Apartheid!

The Observation Post published 5 articles on the The Torch Commando outlining the history of the movement, this was done ahead of the 60th anniversary of the death of Sailor Malan and Yvonne Malan’ commemorative lecture on him “I fear no man”. To easily access all the key links and the respective content here they are in sequence.

In part 1, we outlined the Nazification of the Afrikaner right prior to and during World War 2 and their ascent to power in a shock election win in 1948 as the Afrikaner National Party – creating the groundswell of indignation and protest from the returning war veterans, whose entire raison d’etre for going to war was to get rid of Nazism.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The Nazification of the Afrikaner Right

In part 2, in response to National Party’s plans to amend the constitution to make way for Apartheid legislation, we outlined the political nature of the military veterans’ associations and parties and the formation of the War Veterans Action Committee (WVAC) under the leadership of Battle of Britain hero – Group Captain Sailor Malan in opposition to it. Essentially bringing together firebrand Springbok Legionnaires and the United Party’s military veteran leaders into a moderate and centre-line steering committee with broad popular appeal across the entire veteran voting bloc.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The War Veterans’ Action Committee

In Part 3, we cover the opening salvo of WVAC in a protest in April 1951 at the War Cenotaph in Johannesburg followed by the ratification of four demands at two mass rallies in May 1951. They take these demands to Nationalists in Parliament in a ‘Steel Commando’ convoy converging on Cape Town. Led by Group Captain Sailor Malan and another Afrikaner – Commandant Dolf de la Rey, a South African War (1899-1902) veteran of high standing their purpose is to raise support from Afrikaner and English veterans alike and they converge with a ‘Torchlight’ rally of 60,000 protestors and hand their demands to parliament.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The Steel Commando

In Part 4, in response to the success of The Steel Commando Cape Town protest, we then look at the rise of the Torch Commando as South Africa’s largest and most significant mass protest movement in the early 1950’s pre-dating the ANC’s defiance campaign. Political dynamics within the Torch see its loyalties stretched across the South African opposition politics landscape, the Torch eventually aiding the United Party’s (UP) grassroots campaigning whilst at the same time caught up in Federal breakaway parties and the Natal issue. The introduction of the ‘Swart Bills’ in addition to ‘coloured vote constitutional crisis’ going ahead despite ineffectual protests causes a crisis within the Torch. This and the UP’s losses in by-elections in the lead up to and the 1953 General Election itself spurs the eventual demise of The Torch Commando.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The ‘Rise and Fall’ of the Torch Commando

In Part 5, we conclude the Series on The Torch Commando with ‘The Smoking Gun’. The Smoking Gun traces what the Torch Commando members do after the movement collapses, significantly two political parties spin out the Torch Commando – the Liberal Party of South Africa and the Union Federal Party. The Torch also significantly impacts the United Party and the formation of the breakaway Progressive Party who embark on formal party political resistance to Apartheid and are the precursor of the modern day Democratic Alliance. The Torch’s Communists party members take a leading role in the ANC’s armed wing MK, and the Torch’s liberals spin off the NCL and ARM armed resistance movements from the Liberal Party. We conclude with CODESA.

For an in-depth article follow this link: The Smoking Gun