Liliesleaf, Rivonia (August 1962 –11 July 1963)

By Garth Conan Benneyworth

Abstract

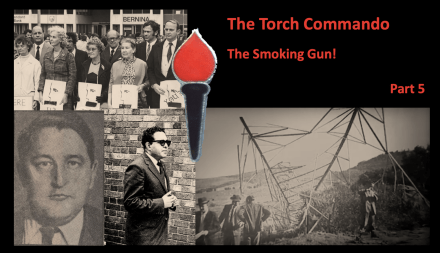

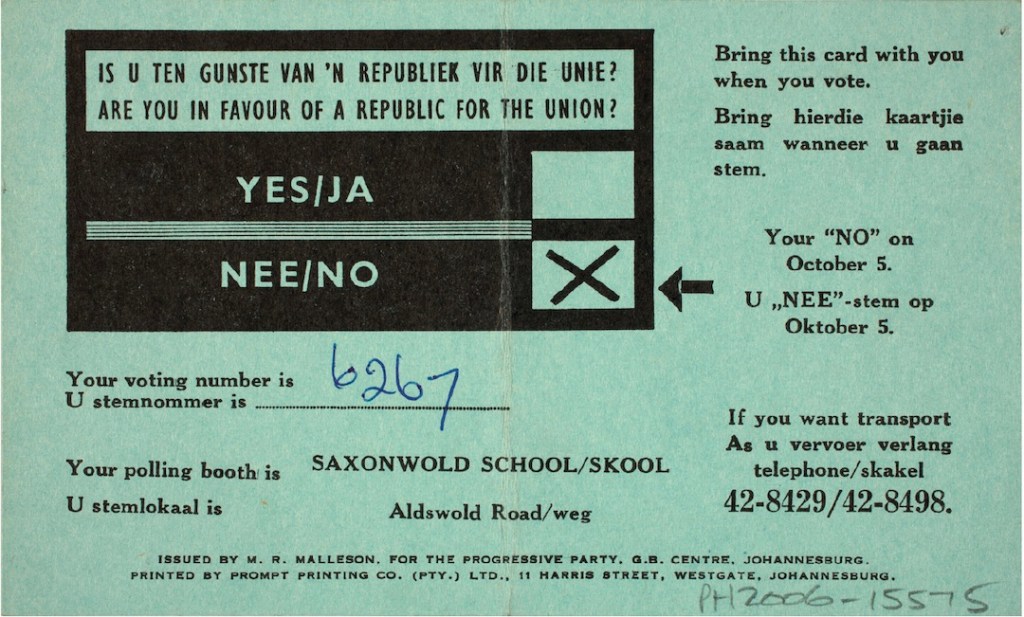

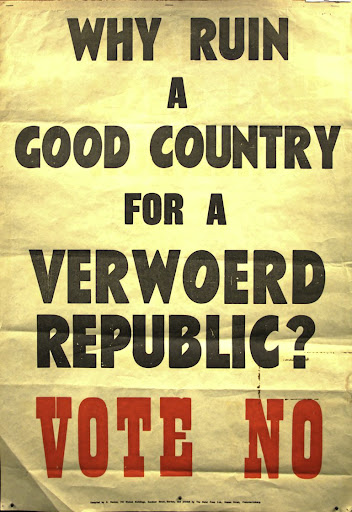

The police raid on Liliesleaf on 11 July 1963 is understood to be the result of informants within the liberation movements either breaking down in detention or “selling out” and providing information about the farm with its safe house and its people. This paper, while acknowledging that there were informants inside the liberation movements, maintains that this was only a fragment of a kaleidoscope of events culminating in the raid and subsequent Rivonia Trial. Rather it was a covert investigation undertaken since 1962 that resulted in the blow delivered by the combined security agencies, that shattered the underground networks opposing the apartheid state. It was an investigation which relied extensively on the principles of the mythological Greek Trojan horse; it used persons and technology that aimed to undermine and overthrow their opponent, to subvert and defeat it from within, while appearing non threatening. This paper identifies three Trojan horses. A human spy concealed behind the innocent look of a child who fronted for sinister forces. Electronic warfare deployed by the military and linked to an innocuous caravan park; and finally a laundry van to deliver the surgical knockout strike. Yet all this subterfuge has eluded the narrative for 53 years.

The build-up, 1963

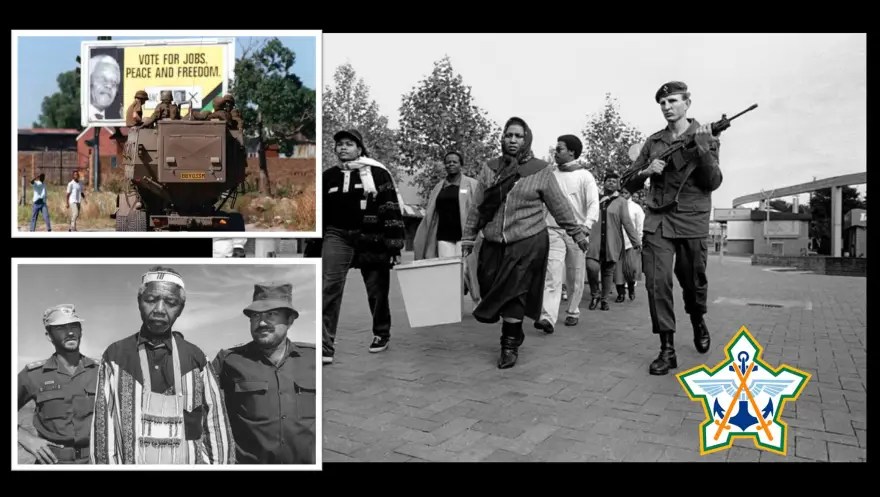

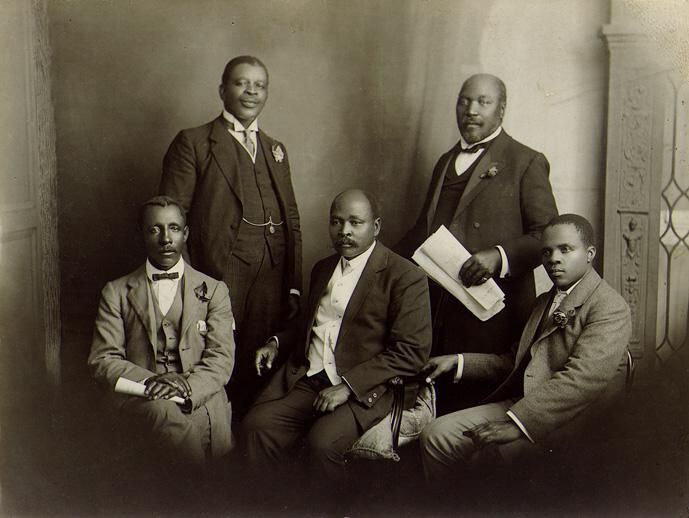

By June 1963 the state crackdown was relentless. Political organisations, such as the African National Congress (ANC), the South African Communist Party (SACP) and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), together with their activists were under banning orders, restricted from almost all social and political contact with others, rendered incommunicado, detained, driven into exile, or serving prison sentences. The PAC’s resistance had been neutralised, numerous political trials were underway and of the various methods exhibited by a growing security police state, one was increasing brutality.

It became increasingly difficult for the members of the underground to operate. Informants were rumoured to be everywhere and the pressure of living beneath the radar became unbearable. At some point a fatal mistake might be made or the sheer weight of the security apparatus might find a leak in the dyke, bursting through to flood into the underground networks.

Dennis Goldberg recalled that there were two sides to operating in the underground.

“It really was as exciting as I imagined it would be. I was a fulltime revolutionary. I felt invincible: on the brink of something great. There was a constant rush of adrenaline”.1

However this came with a price. Goldberg recalled living under this terrible strain:

“What happens when you are working underground is that you’re constantly working under the pressure of discovery; you’re constantly having to think about it. It becomes a terrible anxiety. The pressure of being underground, it was wearing and wearing … and you’re forced into making mistakes. This is what the pressure does, it forces you into mistakes. I am talking about the way the security forces

pressure you.2And this is the lesson to be learnt from it, there is always too much to do, you’re always in a hurry, the revolution must happen today, if not tonight, and so you make mistakes. What it plays on is that eventually you become so lonely, you give yourself away … It’s like a boil. That is part of the psychology. That might not necessarily be the whole thing. But we don’t train our people for this, you only learn it when it’s too damn late.3

There was a nuance of change taking place; one that the movement was slow to detect. Some members had become complacent, lulled by a false sense of security, which appeared to be presented by the façade of the safe house. After all, once inside the perceived guerrilla zone, the hostile world lay beyond its boundaries. Rusty Bernstein saw it as “evident that the ‘safe house’ syndrome was at work. Liliesleaf farm seemed to be the easy option for every hard choice. It was after all safe.”4

Kathrada recalled his emotions when he arrived at Liliesleaf:

“I’m living in another world. The comrades here were completely divorced, Soweto was just a few miles from here, they were completely divorced from reality. And drawing up very fancy documents. They had even forgotten that when MK was formed, no one had the idea that MK was going to overthrow the government. At the very most MK was going to be a pressure group. The goal remained that MK would be one of the pressure groups together with the political struggle, together with the international pressures, to force the enemy to the negotiation table.”5

In 2006, according to Vivien Ezra who owned the front company, Navian Ltd, established by the SACP to purchase Liliesleaf, there were no internal security arrangements within the cells to resist infiltration. 6 Structures just did not exist whereby suspicions could be reported. In short, there was no structured counter intelligence mechanism in use by the underground. 7 Naïve is a persistent word that crept through all the interviews conducted by the author in the period from 2004 to 2006.

Nothing illustrates this better than the fact that although Mandela was captured in August 1962, Liliesleaf continued to be used by the allied organisations, including the SACP, the ANC, MK, members of the Congress Alliance, South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) and members of the Indian political organisations, right up until the raid, eleven months later.

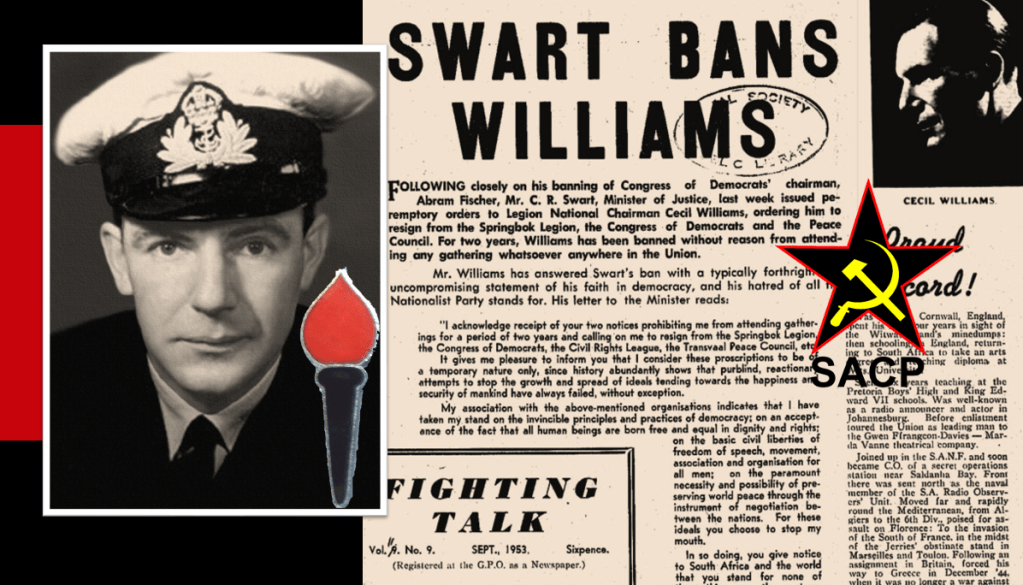

One would have thought that once South Africa’s most wanted fugitive was captured, these organisations would have tried to put as much distance as possible between themselves and Liliesleaf, given that Mandela had used the farm as his base of operations. He had travelled throughout Africa and the United Kingdom, yet it would appear that no one considered the possibility that his movements might be tracked back to Liliesleaf, or that had he been under surveillance, which he was, thus compromising the farm around August 1962 when captured. Mandela claimed that he concealed a revolver and notebook within the upholstery of the front seat of Cecil Williams’s car before being arrested and taken into custody.8 The hypothesis is that the police found this notebook, which enabled them to investigate his activities in South Africa after his return from Ethiopia. The impending danger was that by using this information the security branch could hone in on Liliesleaf. In fact, it appears that that the underground activities and the use of Liliesleaf by the liberation movement actually increased after August 1962 and continued to do so until the 1963 raid. It is possible that more leaders of the underground and operatives sought shelter at Liliesleaf after August 1962, than at any other time in its history before this date. Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba, Wilton Mkwai, Andrew Mlangeni, Govan Mbeki and Ahmed Kathrada certainly did, to name but a few. Meetings of MK’s high command, the Secretariat and the SACP’s central committee were held there, and quite possibly also the ANC’s NEC and various MK committees such as those dealing with intelligence, logistics, transport and housing.

It is widely understood that the meeting of the Secretariat on the day of the raid was the last meeting held at Liliesleaf and that thereafter other venues would be used. Some had serious reservations about returning there believing the farm to be compromised. Bernstein was vehemently opposed to returning to Liliesleaf. 9 Other senior leaders, such as Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba and Wilton Mkwai no longer stayed there, having moved to Trevallyn, a smallholding near Krugersdorp, purchased shortly before by Denis Goldberg under a fictitious name. Meanwhile, Liliesleaf was to be used solely for accommodating the MK high command and those immediately involved in its functioning.10 However this was not the case for that one fateful meeting. The Logistics Committee was due to meet the night of 11 July 1963. So in fact two meetings were intended at Liliesleaf on the day of the raid. All of those captured during the raid concur that because an alternative venue couldn’t be found, it was agreed to meet at Liliesleaf one last time.

Yet other parallel activities were occurring, such as a scheduled Logistics Committee meeting, planned to take place inside the main house after the Secretariat concluded its business in the thatched cottage. One of its members, Denis Goldberg was already seated in the lounge reading a book when the veranda door swung open to initiate his capture. Another member, Arthur Goldreich, drove home into the raid with a copy of Operation Mayibuye concealed behind his vehicle’s hubcap. A third, Hilliard Festenstein, walked into the house punctually that night to attend the meeting which never happened – straight into the arms of the police. The chairman of the Logistics Committee, Wilton Mkwai, narrowly avoided capture when approaching the farm as scheduled and saw the raid already in progress. A fifth member, Ian David Kitson, escaped due to a bout of flu which had kept him in bed; while the reasons for Lionel Gay’s non-show remain unknown.

All those at Liliesleaf that day were arrested. The exceptions were six children, three black and three white. Together with other members of the liberation movement who were serving jail sentences or who were arrested elsewhere, those arrested stood trial in what became a watershed moment in South African history. Rivonia.

Leakage

Liliesleaf was leaking. A few weeks before the raid some MK members had visited the farm and were arrested. It was a matter of time before the security branch broke them. By July 1963, there were numerous security lapses so it was inevitable that if the police hadn’t already done so, they would soon find the farm. Apart from which, “we were total amateurs. You cannot cross both worlds, indefinitely”. 11

The concept of security had broken down. Too many people were using Liliesleaf. Its numerous visitors included people who were known to the security branch and foreign intelligence agencies, such as Joe Slovo, Ruth First, Jack Hodgson, Bram Fischer, Lionel Bernstein, Harold Wolpe and many others. Lionel (Rusty) Bernstein described this osmosis from the safe house:

“Later people who had been overseas for military training would arrive back in Bechuanaland without any proper planning. The first thing we would know was that they were in Bechuanaland and wanted come back. So we’d bring them back and they would stay for a few nights … Rivonia came into sudden use in a way that had not been foreseen.

So this place became a sort of centre, if you like because Sisulu and Mbeki were the two senior ANC people at large at that time. [Since] both of them were [also]participating on the high command, they began to use it for MK high command activities, both for keeping documents and holding meetings, and they were bringing people to their meetings who were not in the high command, not living underground and so on. So the place really changed from being a really closely kept secret to being something of a centre.”12

Even Thomas Mashifane, the foreman, could sense the inherent danger building up. “What are you folks doing? The way motor cars are coming in and out, the next thing the police are going to come.” 13 No one was prepared to listen. The question is, where others listening with a more sinister intent? Had those with a little more intellect than ascribed to them, applied themselves as opposed to the thuggery displayed by the police? Had the proverbial Mr Plod finally caught up?

The central thread that runs through the literature is that the security branch experienced a lucky break when they raided Liliesleaf farm. Starting in 1965, Strydom has it that an informant offered to tell what he knew about activities at the farm, yet had only a vague idea where it was. Accompanied by a detective and after driving about the area for some time, he eventually recognised the property.14 Frankel has it that Lt. Van Wyk who led the raid was advised by a colleague that he had an informant with information to sell. Apparently he knew where to find Walter Sisulu and half a dozen other important leaders of the Umkhonto high command. For a large payment he would take the lieutenant there.15 According to Frankel the informant took Van Wyk to Liliesleaf, enabling him to plan the raid which he sprung the following day. After the raid the informant received R6 000.16 More recent works, for example that by Smith, have the security branch depicted as a proverbial Mr Plod staffed with bumbling policemen who eventually caught up with the activists.17 If so, who was listening in besides the SAP and its security branch?

This paper will show that at least three parallel lines of investigation by three separate security agencies took place between 1962 and the day of the raid. There could have been other agencies but these remain unidentified. The three agencies were the SAP’s security branch, using its methods of informer recruitment and information collected; Republican Intelligence (RI), using informants and information trading with foreign intelligence organisations (later better known as the National Intelligence Service or NIS); and the South African Communications Security Agency which was linked to the South African Defence Force (SADF).

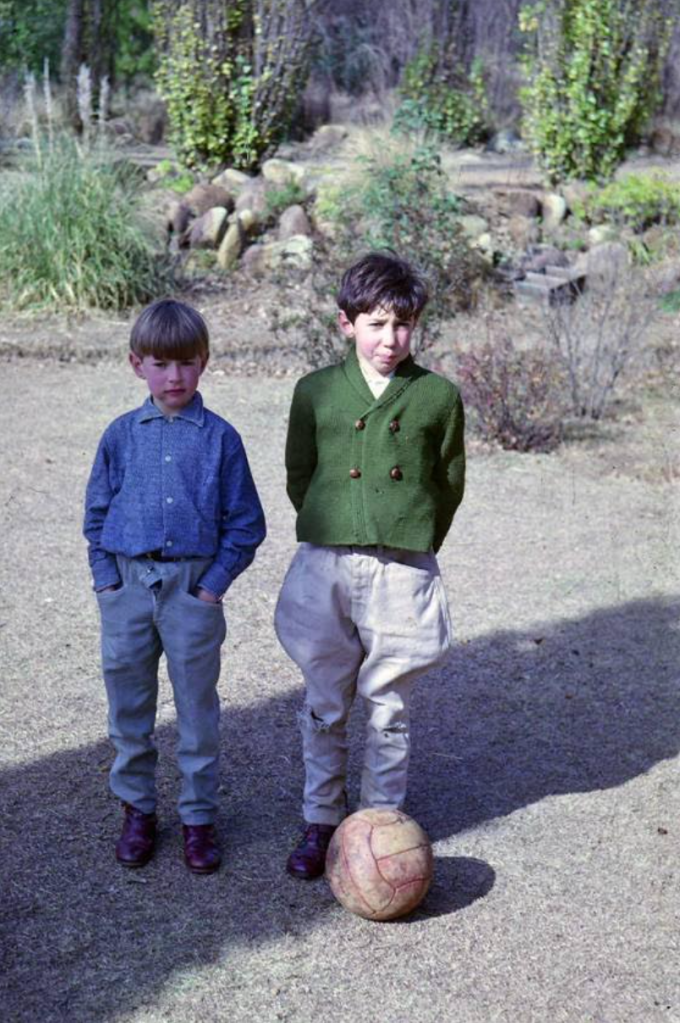

Investigating Liliesleaf, 1962-1963

There is no doubt that captured operatives gave the police information. Examples include Bruno Mtolo, Patrick Mthembu and Bartholomew Hlapane.18 However, this paper will identify one informer whose role the author uncovered in 2005 by locating this informant’s 1963 statement to the SAP. A copy was provided by the author to the Liliesleaf Trust in 2005 and is included in an unpublished research report to the Trust in 2007.19 All subsequent references to this informant are drawn from the author’s prior work. Within weeks of Nelson Mandela’s capture on 5 August 1962, the security branch had a ten-year-old informant who had access to the farm. His name is George Mellis. His parents owned the Rivonia Caravan Park directly across the road from Liliesleaf. He was the perfect Trojan horse. He could literally breach the sanctity of the safe house undetected, much like the mythical Trojan horse parked outside the gates of Troy. No one gave the boy so much as a second glance when he arrived to play with his friends Nicholas and Paul Goldreich, or wandered around near the outbuildings while covert meetings were underway.

On 5 August 1963, George Mellis made a sworn statement to Sergeant Fourie who commanded the Rivonia police station.

“About a year ago, one day when I was playing in the yard of the Goldreichs’ place, I saw a number of white and Bantu males together in the thatch-roof building next to the main house. These people were talking and I saw some shaking hands with each other. This seemed strange to me and I told my parents about it. On some occasions that I went there I saw a lot of cars parked in the yard and one occasion,

I took the registration numbers of all the cars parked in the Goldreich yard and handed the numbers I had written down, to the police at Rivonia.” 20

Sergeant Fourie forwarded Mellis’s number plate list and his information to the security branch. Mellis tried to elicit further information from his Goldreich playmates whom he joined inside the main house for lunch. On one occasion, he said, “I asked Nicholas about the persons on the premises but Nicholas said that he was not allowed to tell me anything”. 21

In his 1963 statement Mellis identified Walter Sisulu Raymond Mhlaba, Denis Goldberg and Ahmed Kathrada from police photographs. His Goldberg reference is pertinent in that Goldberg first visited Liliesleaf in May 1963. This means that Mellis was spying on Liliesleaf from the time of his first report (about a year before the raidand soon after Mandela’s capture), through to when Goldberg visited Liliesleaf between May and July 1963. Mellis spied right up until the raid.

Sergeant Fourie assisted the security branch too. In December 1962, Fourie received a summons for a parking offence from the Alberton magistrate’s court which he had to serve on Arthur Goldreich. Fourie held back.

“Aangesien ek bang was dat dit met die ondersoek mag inmeng het ek die lasbrief nie laat uitvoer nie maar het die agterwee gehou [Because I was afraid that it might interfere with the investigation, I did not serve the summons but held it back.]”.22

Fourie instructed his policemen that any action against anyone at Liliesleaf, for example serving a summons, should first be cleared with him. No policeman was to go onto Liliesleaf for any reason without prior authorisation, because an investigation was underway. The farm was sanitised from any official physical interruption.

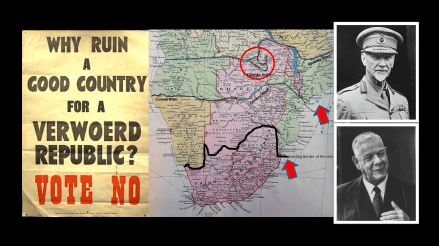

On 14 January 1963, Colonel Hendrik van den Bergh was appointed head of the security branch of the South African Police. His orders were to reorganise the South African security establishment and it was he who created the first national intelligence service, originally known as Republican Intelligence (RI). The government needed an intelligence organisation that could function along the lines of America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS). The RI, together with the security branch, were instructed to smash all organised resistance to the minority regime.

According to Gerhard Ludi the RI’s primary focus was the South African Communist Party (SACP). Ludi, one of RI’s first agents, has suggested that the RI identified the SACP as the primary problem confronting the apartheid regime. Ludi has said that the CIA assisted RI and provided intelligence about financial assistance that Russia provided to the liberation movements. The CIA also indicated who the KGB operatives in South Africa might be and pointed out some of the local communists to the RI.23 RI fed intelligence to both the CIA and the SIS on a weekly basis and these agencies reciprocated. This foreign intelligence feed also included information about Operation Mayibuye and Radio Freedom, both implicitly connected to Liliesleaf.24

Ludi related that RI took the approach that, “if one learned about the cores of the Communist Party, one would learn about the why and where and the role the Soviets were playing in this”. 25 Persons of interest who formed their intelligence target were Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Michael Harmel, Lionel Bernstein, Hilda Watts, Harold Wolpe and Ahmed Kathrada. Ludi said that Mhlaba, Bernstein and Harmel would be of particular focus for RI.

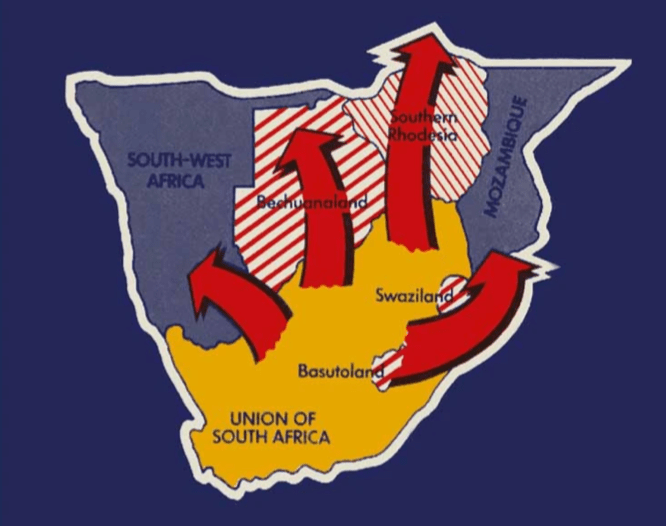

Liaison between the apartheid regime and other regimes in Southern Rhodesia and the Portuguese colonies was improved and intelligence sharing became the established modus operandi. Cooperation with the Portuguese extended into their Angola and Mozambique colonies and surveillance reports were provided to government about the movements of known South African communists such as Ruth First, Hillary Plegg, Ben Turok, V.W. Mkwai, Moses Mabida, Julius Baker and P. Beyleveldt who were travelling through Portuguese controlled territories.26 The Portuguese assisted the SIS in monitoring MK activities. In 1961 Portuguese Naval Intelligence transmitted an intelligence report to SIS that Ghana was recruiting South Africans for political, military and sabotage training and supplying funds to SouthAfrican anti-government groups.27

Ludi claimed that RI was, “instrumental in pin pointing Rivonia through the radio”. 28 This was the radio transmitter linked to Walter Sisulu’s Freedom Day, Radio Freedom broadcast on 26 June 1963. It is important to note that this broadcast did not occur at Liliesleaf although the radio equipment was tested there. Ludi claims that one of his agents was an electrical engineer; he was connected to the SACP transport manager who knew someone who ran a dry cleaning operation and whose vans were used to transport underground operatives around the country. This link to a dry cleaning van is another Trojan horse. Someone connected to the underground structures used a vehicle like this one, and inside the van lurked an RI agent. This also shows that the routines at the farm were already under surveillance. They were understood, mapped and logged; a Trojan horse disguised as an innocuous laundry van was the modus operandi when the knockout blow was delivered.

The agent met the go between at a bus terminus where he was tied up and blindfolded inside the van. Driven to Liliesleaf he was shown the radio and commented, “This is the most antiquated piece of rubbish I’ve seen in my life.” He couldn’t do anything with it, but the information assisted RI who now knew that somewhere in that area:

“There was a place where things were happening and I believe that after we fed that information to the police that they then started driving … patterns in that area looking for something they thought must be happening there and that’s how they actually found Rivonia, plus of course somebody also gave them information.”29

Who gave the police information is a moot point – informants or another process? While the role of the security branch and RI is known, what is not known is the role of the SADF and its electronic warfare capabilities in locating Liliesleaf. Research and development into electronic warfare began in the early 1950s in response to SACP underground radio broadcasts. By the early 1960s their direction finding technology was on par with the British and Americans.

In about 1955/56, the Radio Section of the engineers’ section of the general post office (GPO) was tasked to assist the SAP to locate the source of Radio Freedom broadcasts that transmitted on short-wave wavelengths. The SACP transmitted on Sunday evenings at 20h00 for 15 minutes. The Radio Act No. 3 of 1952 stipulated that a conviction could only result if the police caught the perpetrators in the act of broadcasting. 30 As the SAP and the Union Defence Force (later the SADF) had no direction-finding capability to comply with this stipulation of the Act they turned to the GPO. The Derdepoort Radio Station based at Hartebeesfontein farm near Pretoria was given the task. Having no direction finding equipment they then developed their own.31

Transmissions were identified as coming from Natal. They then built a mobile direction finding facility and installed it in GPO vans and undertook the search. After nine months the operation halted without success. During early 1956 the transmissions resurfaced in the Johannesburg/Pretoria area. Each transmission came from a different location thus requiring greater mobility. Derdepoort’s technicians developed man-pack equipment which could be carried while walking. The SAP flying squad drove these operators (known then as chase teams). Three vehicle mounted direction finding units and five man-pack units were deployed. Included in the chase teams were technicians from Derdepoort station. The security branch supported the operation. 32 On Sunday 12 August 1956, they identified 363 Berea Street Muckleneuk, Pretoria and raided the house, seizing the transmitter and other equipment along with a pre-recorded taped broadcast. The four accused were convicted of violating the Radio Act No.3 of 1952, a relatively minor offence, and sentenced to a fine of ₤50 or six months in jail. 33

Following this the engineers’ section acquired more sophisticated equipment to facilitate their direction finding methods. In 1958, they imported the Adcock System from the USA, the most advanced of its kind at the time. Located at Derdepoort, this static system included an all-round direction finding capability. 34 Cooperation on direction finding operations between the GPO and SAP was not unusual for this era. Britain’s Security Service MI5, used British post office technology in its counter intelligence operations, both in the United Kingdom against Soviet agents and operations, and also during military operations against independence movements in its colonies, such as in Cyprus.35

The role of the SADF and South African Communications Security Agency

In 1960/1961 the SADF established an overarching telecommunication function, the South African Communications Security Agency (SACSA). SACSA fell under the directorate of telecommunications, and its director was accountable to the prime minister at the time, H.F. Verwoerd. SACSA’s duties were enabling secure and un-compromised communications between all government departments. This included all arms of the SADF, the Department of Foreign Affairs, military attaches abroad, and between the SAP and its agents. 36

During 1963, SACSA played a key role in locating and spying on Liliesleaf. On 1 April 1963, Captain Martiens Botha was transferred to defence headquarters Pretoria to work for the chief telecommunications officer. Included in this small team was Captain Mike Venter of the South African Air Force (SAAF) who was proficient in Morse code. One of his duties was monitoring radio transmissions that the authorities deemed as subversive. Venter detected suspicious Morse code messages inside the country and showed them to Botha. Venter’s information was reported to the security branch and

to RI. 37

SACSA borrowed a direction finding vehicle from the post office telecommunications section and pinpointed the location to within a few blocks of where the transmitter was located. This was enabled because, according to Captain Venter, the Morse code transmitter burst its signals more than once from Liliesleaf. SACSA then searched for visibly suspicious equipment such as antennas on properties in the area. Liliesleaf had two lightning conductors next to the main house. 38

SACSA observed and noted all these activities. Mary Russell and her husband lived in the Rivonia Caravan Park directly opposite the Rietfontein Road entrance into Liliesleaf. After the 1963 raid, Russell later shared her observations with her family, saying that, she “knew something was going on across the road”. 39 In 2005, Russell’s nephew, Gavin Olivier, shared this account with the author. According to Olivier, Russell was an avid birdwatcher and used binoculars to observe the birdlife from her veranda. Prior to the raid, she saw postal workers standing on ladders erected against telephone poles along Rietfontein Road, working on the telephone lines. For Russell, it was odd that they stood atop for long periods of time and used binoculars. Russell recalled what she described as “mysterious bread delivery vans” parked inside the caravan park several times a week for the entire day. Strange, she said, “we don’t have a shop that sells bread in the caravan park.” 40 Yet there they were opposite the driveway into Liliesleaf. Paul Goldreich also recollected men working on telephone cables outside the farm.41

July 1963 was a cold winter, yet shortly before the raid, from at least May 1963, Denis Goldberg recalled there being a single caravan inside the park. Its presence made him feel uneasy.

“There was only one caravan there most of the time, and this area was so far out of Jo’burg, it was deep countryside … And there was this caravan park, which was bare red earth with what I remember as one caravan. A very sleepy police station around the corner. I believe they said they watched the place, this is what I am basing it on … it would have been the obvious thing.” 42

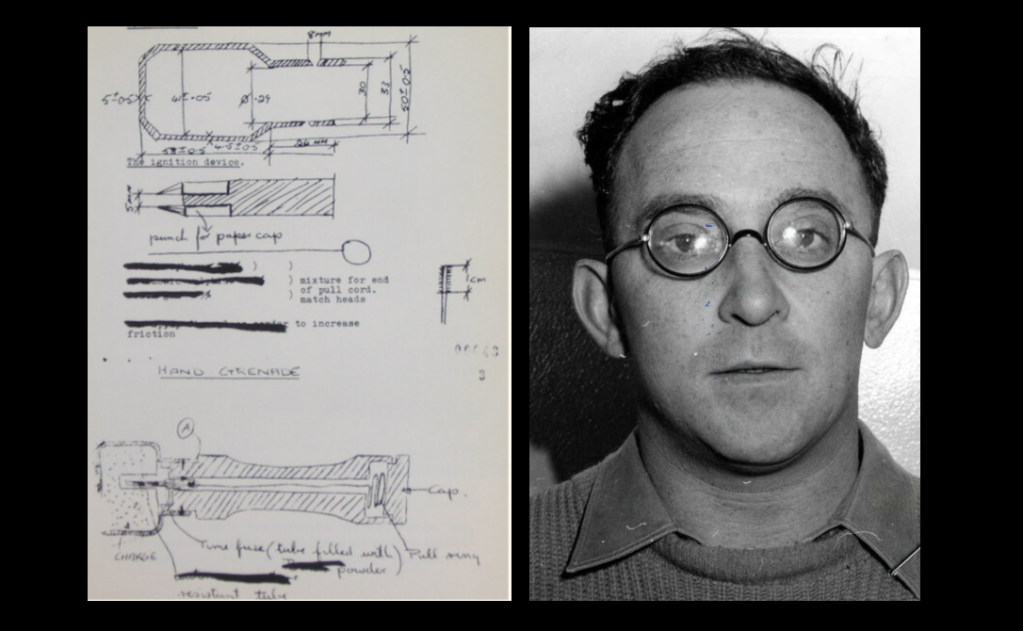

The Trojan horse was literally across the road, parked inside a caravan park owned by the Mellis family, who were actively assisting this investigation. There is other evidence of electronic surveillance activity, all intersecting towards July 1963. In 2005 the author interviewed an individual who wished to remain anonymous. This person claimed that in 1963 he had supplied the security branch with RM 401 hearing aid microphones together with long life batteries which lasted about a month. The microphones and their batteries fitted into a human ear, making them ideal for covert listening. These bugs could be disguised and planted anywhere and were small enough to be inserted into a pen and worn by an informant during a conversation; three or four such devices fitted into a matchbox. The microphone and transmitter worked at low frequencies, and the range was as much as 1⁄2 km to a listening station located within a line of sight.

The receiver for these devices was very powerful. The signal did not need to be very strong and the microphone did not require a large opening, a pin hole would suffice, as in a standard hearing aid. The listening station required a sizable aerial, about one metre in length. It could be erected in a tree; run along telephone wires; concealed inside a roof; or tucked out of sight inside a caravan. It could even masquerade as a car aerial if parked nearby.

If inserted inside a building then transmission distanced would be reduced and to compensate for this, some type of aerial would have to be attached to boost the transmission. An option was a shortwave radio, working at 10 MHz, providing there was a good receiver on the receiving end. If the transmitter was outdoors the range would increase and the only limitations would be caused by background noise. These transmitters picked up sound in an entire room, and the next room as well. The bug could be concealed in a light switch and fitted by an electrician or plumber. It could be hidden beneath a car or anywhere else and camouflaged to resemble any type of contextual object. Lightning or electrical activity did not affect its performance.

Police purchases began with a phone call to check for available stock; followed by a visit from two plainclothes policemen. Payment with was cash and no receipt was required. Prior to the raid, as many as 1 000 units may have been supplied. When news of the Liliesleaf raid broke, the salesperson thought, “So that’s where all our microphones were going! Damn sure in my own mind – bloody hell, so that’s where our microphones went!” 43

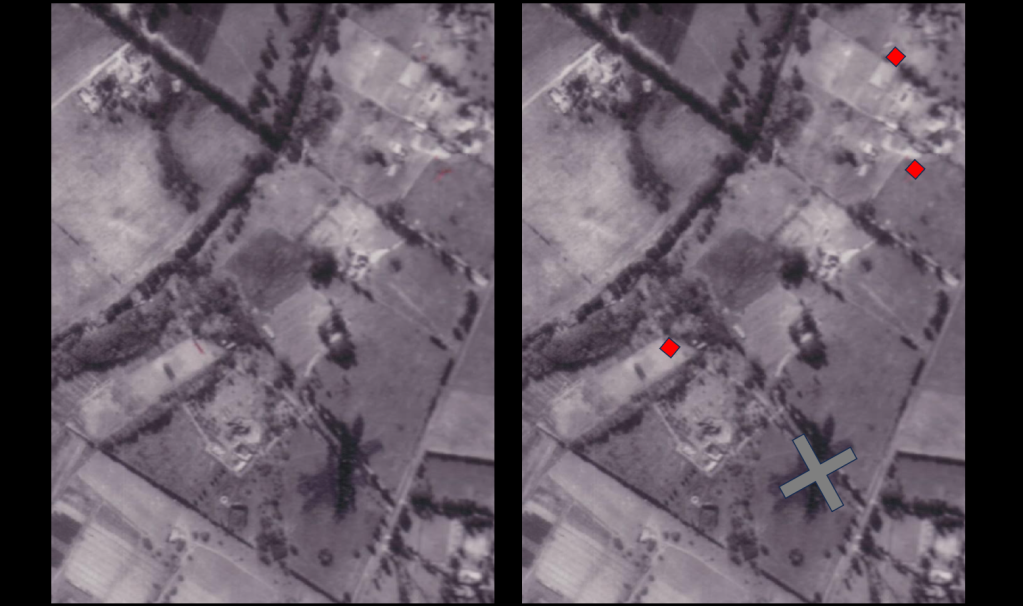

In 2004 the author uncovered additional tangible evidence of a surveillance operation. In 1961 the surveyor general updated the cadastral maps and the Rivonia area was aerially re-photographed to produce maps in 1962. Each photographic contact sheet covers a vast area and nothing distinguishes a particular property from the next unless the sheets are significantly enlarged. The next photographic series dates to 1964. The author scanned the sheets depicting Liliesleaf in the 1961 and 1964 mapping process in high resolution. One of these sheets revealed a trace of the SACSA direction finding andelectronic warfare operation. (None of the 1964 photographs reflect any tampering). Three microscopic red dots and a pencil cross (x) emerged when a high resolution electronic scanner was used. Two red dots are on a neighbouring property. One red dot marks the approximate centre of Liliesleaf farm and the pencil cross on the sheet marks the dirt driveway leading into Liliesleaf, directly across the road from the caravan park. 44

Someone involved in this investigation examined this contact sheet and made the markings before returning the sheet assuming that the microscopic tampering would remain invisible. Not only was the SADF proficient in electronic warfare. The technical skills of the SAAF, the second oldest air force in the world, were on par with its international counterparts. In combat operations in Africa, Madagascar and Europe during the Second World War, the SAAF made extensive use of aerial photo reconnaissance. Nor were their skills of electronic warfare neglected in the post-war years.

In 1957, the SAAF acquired the Avro Shackleton MR Mk3 which it used for long range maritime patrolling and naval surveillance operations. 45 Between 1962 and 1964 the SAAF acquired 16 Mirage IIIC fighter aircraft from France, followed by four Mirage RZ fighter reconnaissance aircraft. 46 In late 1963, SAAF took delivery of the Canberra B (I) Mk 12 heavy bomber and photo reconnaissance aircraft from Britain. It was adding to and upgrading its technological capacity. Consequently, in 1962 to 1963 the only agency with the technical skills capable of identifying targets from aerial photographs of Liliesleaf was the SAAF.47

Thursday 11 July 1963

A meeting on Saturday 6 July 1963 to discuss Operation Mayibuye at Liliesleaf deadlocked. The plan was not approved and it created deep divisions within the Secretariat and amongst members of the SACP’s Central Committee. The plan had to be either approved by the political structures, which did not happen, or be sent back for further work. However, the next part of the problem was a practical one: where could the Secretariat meet and when? The matter had to be speedily resolved, yet the issue of a venue was becoming contentious and downright dangerous.

There were a number of people who did not want to return to Liliesleaf. According to Goldberg:

“They had earlier taken the decision not to bring people who were not living underground to the place where others were living in hiding. Too many people had been to Liliesleaf farm. The security risks were great. We urgently needed a different place and the task of buying somewhere new was given to me because I could legally buy property.” 48

A number of the senior leaders, such as Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba and Wilton Mkwai no longer stayed at the farm, having moved to Trevallyn, a smallholding near Krugersdorp, recently purchased by Goldberg under a fictitious name and which was to be used solely for accommodating members of the MK high command and those immediately involved in its functioning. 49 Goldberg later wrote that “the last meeting of the High Command at Liliesleaf was one too many”. 50 Goldberg remembered:

“They didn’t have time to arrange a new venue, so we had to come back here, knowing that it was dangerous to come here. The decision had been taken, no more meetings at Rivonia. Yet we had one more, because of the pressure of Rusty’s house arrest.”51

Kathrada recalled:

“A number of us started feeling uneasy about the continued use of the Rivonia farm. We were well aware that the need-to-know principle had not applied to Liliesleaf for some time, and that far too many people – one of whom was Bruno Mtolo, a saboteur from Durban and leader of the Natal branch, had visited the farm. But there was no avoiding one final meeting in Rivonia. In the days leading up to this crucial gathering, I became more agitated and afraid. The only person who I could share my views with was Walter Sisulu, whose views coincided with my own.”52

As for Bernstein, he was not in favour of holding the meeting there. He had lost faith in

Liliesleaf as an uncompromised venue:

“I don’t even remember who convened the meeting. I know I didn’t want to go to it. I was afraid of the place. It was Hepple who persuaded me. [He said] “Okay, you don’t want to go to this place, just this one last time”. Famous last words.53

The next issue was the timing of the meeting. Which day might be appropriate? Thursdays were delivery days. Produce from the butcher and grocer were delivered; dry cleaning collected and dropped off; cars came and went – these goings-on were an established routine. Because these activities had doubled up as a screen for meetings before, Thursday it would be. However, these routines were known and identified, all watched and listened to inside the Trojan horse parked innocently in the caravan park.

Nothing untoward happened during the day except for Bob Hepple’s encounter with an unidentified individual which alludes to a covert investigation.

“On the morning of the 11th July, a man came to my chambers. He was an Indian. I had never met him before. And he said to me, “I have got a message for Cedric from Natalie.” Now I knew that I regularly received letters addressed to me at my chambers. Inside was an envelope sealed from Natalie for Cedric. And I knew these were for the leadership and I would deliver them personally to Liliesleaf Farm. And I wondered what was going on because Cedric was the codename for the centre and Natalie was the code name for the Natal district. And I knew these names on letters would come to my chambers addressed me. I would open them …and would take them over. Who was this guy? I had no knowledge of him. I fobbed him off. I said I don’t know what this is about but I’ll look into it and see. So I realised he was bringing some message. But I didn’t know if he was genuine, he could have been a police spy. And I was deeply suspicious. I feigned ignorance and said I have to go out now and sent him away and said come back to me tomorrow morning. My idea being to make enquiries if anyone knew what this was about. So the result, I was very worried and it was one of the things when I did go there that afternoon that I was worried about. So on my route there I was extremely nervous, I kept thinking maybe I am going to be followed.” 54

This encounter unnerved Hepple. According to him there were already suspicions that the CIA had had a hand in Mandela’s capture. For what reason and by whom was this visitor sent? 55 Hepple told Kathrada about his suspicious visitor and Kathrada confirmed that he too had received a garbled message from someone who mentioned Cedric. After ten minutes of exchanging pleasantries, the six took their seats inside the thatched cottage, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Walter Sisulu, Lionel Bernstein, Bob Hepple and Ahmed Kathrada. Their agenda was to discuss the impact of the 90 days arrests and to continue the discussion on Operation Mayibuye.

Bernstein held the Operation Mayibuye document on his lap so that he might refer to it and started his critique. No sooner had he commenced when they observed a dry cleaning van, bearing the logo Trade Steam Pressers through a rear window driving down the driveway. It drove up and parked next to the house. Bernstein looked out the window and exclaimed. “Oh my God, I saw that van opposite the police station this afternoon!” 56 The Trojan horse was in position. Perfectly timed and synchronised to the exact moment that the meeting started. Certainly no coincidence. Coordinated by another Trojan horse parked inside the caravan park and listening in. Suddenly the rear doors of the dry cleaning van opened, disgorging the security branch police with their attack dog. While the raiders encircled the main house, Govan Mbeki snatched the Mayibuye plan from Bernstein and tried to burn it but without matches it was useless. Mbeki then shoved the plan into the stovepipe chimney.

Mbeki, Sisulu and Kathrada leapt through a rear window but were immediately caught. The remaining three hoped to bluff their way out. Detective Kennedy opened the door and rushed inside. “Stay where you are. You’re all under arrest!” 57

The three were then escorted outside. Hepple recalled that by this stage the place was piling up with police and dogs. This suggests that the dry cleaner’s van was the initial probe – the Trojan horse. Once it had breached the gates and parked inside, its occupants would disgorge to secure the buildings while the main body, already in position on Rietfontein Road would then swoop in and overwhelm the farm, while securing the perimeter.

Earlier, in the lounge, Goldberg looked up to see Lt Van Wyk swing open the veranda door and step inside, only metres away from where he sat. Goldberg leapt from his chair, grabbed his coat which contained his notes about weapons manufacture and manufacturing quotations which he had received – and made a desperate dash to reach a toilet to flush them away. Intercepted by another policeman entering through the kitchen he was overpowered in the entrance hallway and arrested. “It was a disconcerting moment. Actually what I thought was, oh shit, we’ve been caught.” 58

The suspects and farm labourers were handcuffed inside the dry cleaner’s van. At about 17h50 Arthur Goldreich drove down Rietfontein Road in his Citroen. 59 When he drew level with the entrance gate he noticed two men wearing the hallmark raincoats of plain clothes policemen, standing beneath a tree in the caravan park, talking to each other. It wasn’t raining and they weren’t relieving themselves.

“And my first thought was special branch, and my second thought was I am late. I can’t just drive by. Then the third thought of mine was how come the guy who’s supposed to be guarding the gate is not there … and I came down the driveway, there were trees on either side and from behind the trees came some police and some dogs. And they jumped on the motor car, and the guy with a pistol in his hand put the pistol to my head, and I heard someone shout, “moenie skiet nie!” So I switched off the engine and rolled down and came in towards the garage.” 60

Arthur’s car ground to a halt. He got out, hands raised above his head. 61 At around 18h00 after each captive had been shown the contents of the outbuildings, Bernstein and Hepple joined Mbeki inside the laundry van. Goldberg was then brought out of the house, four policemen climbed into the van and the Trojan horse drove them off. Having breached the gates of the safe house the Trojan horse left with its captives handcuffed inside, facing the horrors ahead, fearing the worst, potentially a death sentence. Passing the solitary caravan parked in the red dirt of the park. Into the dark. The Rivonia Trial followed.

Conclusion

Colonels Van den Bergh and Klindt arrived after sunset. Arthur Goldreich was taken into the main bedroom for a one-on-one monologue delivered by Van den Bergh. Among other things Van den Bergh said:

“The trouble with you, Goldreich, and the trouble with all of you, is you’re amateurs. You always have and you always will underestimate your enemy. And that’s why you’re in the shit.” 62

Liliesleaf and all that was linked to it was captured. The Rivonia Trial followed and after that more arrests and trials until the internal networks were neutralised. A blow most certainly, yet not one which was terminal to the forces of liberation. In the 53 years since the raid the focus on what led to the raid has always been on the security branch. These accounts claim that the SAP, assisted by informants from within the movement, were able to raid Liliesleaf and were lucky to have achieved the success that they did. Kathrada later wrote that the police had the farm under surveillance for some hours before the raid. However, according to him the no one had ever found out the truth:

“ … every version that has been bandied about over the years is based on nothing more that speculation.” 63

The author concurs with Kathrada’s statement. Starting with Strydom in 1965 and weaving through into the recent past with Frankel, popular notion has it that an informant or informants “gave up” the farm to the security branch and fed their information to Lt. Van Wyk who, on receiving it, literally sprung the raid the following day. In a massive twist of fate and coincidence, good luck for some and horrific luck for others, in a single swoop the raid netted prominent leaders connected with MK, the ANC and SACP, together with a haul of documentary and other evidence. This smashed the leaders of organised resistance to the apartheid regime in one massive lucky break, all a result of informants. The security branch pulled it off all on their own. So the story goes. This article demonstrates that to be a fallacy.

By means of an inter-agency investigation into Liliesleaf, this paper outlines some of the complex ways in which the combined security services used a range of techniques and tactics in an attempt to destroy armed opposition to apartheid. One agency was the security branch; its investigations commenced weeks after Nelson Mandela was captured, and later in 1963, the RI and the SADF joined the probe, which led eventually to an operation culminating in the raid. The hypothesis is that information in Nelson Mandela’s notebook and other sources enabled the security branch to identify Liliesleaf. Evidence of the investigation by the security branch soon after Mandela’s arrest is seen in the actions of the first Trojan horse, a young boy, George Mellis, who was able to observe events from within. He was the perfect spy; he passed on information to the Rivonia police station; no one gave him so much as a second glance. However, he would have been carefully handled both by his parents and the security branch, given that he was a minor. Additional evidence of a security branch investigation in 1962, assisted by the Rivonia police station, was the matter of holding back a summons to be served on Goldreich. By December 1962 a determined investigation was underway, so much so that the police sanitised the farm and there were instructions that no policemen were to enter the property.

Mellis’s parents owned the caravan park which offered an ideal position from which to conduct surveillance. A caravan was the second Trojan horse, innocuous on the outside yet filled with electronic equipment, it listened into conversations held at Liliesleaf via hearing devices and telephone line interceptions. Operated by SACSA the timing of the raid could be carefully calculated, which indeed it was. In position during the weeks leading up to the raid, they also detected the Radio Freedom transmitter being tested when it was switched on. The predictably of activities on a Thursday were all observed and calculated. This Trojan horse in turn linked to other SADF technologies of direction finding, electronic warfare and aerial reconnaissance. Evidence of this was provided by those who saw the “postal workers” equipped with binoculars working on the telephone lines. Postal vans and bread delivery vans were seen parked in the caravan park. They were being covertly used by the SACSA. The contact sheets in the surveyor general’s office bear evidence of aerial target identification and the only organisation with the requisite skills to undertake this task, was the SAAF.

The final deception was the third Trojan horse, a laundry and dry cleaning van. Prior to the raid at least one RI spy had accessed the premises in a similar van, so the tactic of using a laundry van to breach the safe house was the ideal choice. Like the mythological Trojan horse which breached the gates of Troy, it was driven inside the farm to disgorge the policemen and their dogs.

In conclusion this paper demonstrates that there was far more to the raid than what has been written about it since that fateful day. It was not merely a police strike. Key roles were played by the SAAF and electronic surveillance was carried out by the SACSA in the state’s offensive against MK. This challenges the commonly held view that the military was not involved in the counter-insurgency operations of 1962 1964. In conventional accounts of the period, the South African military only became involved in counter insurgency when P.W. Botha gained political ascendancy and together with General Magnus Malan, made the notion of Total Onslaught the apartheid government’s strategic doctrine. This paper shows just how heavily involved the military and the security agencies were against MK soon after its formation in 1961.

Written and Researched by Dr. Garth Conan Benneyworth

References

Bernstein, L., Memory against Forgetting (Penguin, London, 1999).Dingake, M., Better to Die on One’s Feet (South African History Online, Cape Town, 2015).

Ellis, S., External Mission: The ANC in Exile (Johnathan Ball, Johannesburg, 2012).

Frankel, G., Rivonia’s Children (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1999).

Goldberg, D., The Mission: A Life for Freedom in South Africa (STE Publishers, Johannesburg, 2010),

Hepple, B., Young Man with the Red Tie: A Memoir of Mandela and the Failed Revolution: 1960-1963 Jacana Media, Johannesburg, 2013).

Kathrada, A., Memoirs (Zebra Press, Paarl, 2004).

Mandela, N.R., Long Walk to Freedom (Abacus, London, 1994).

SADET, The Road to Democracy in South Africa Volume 1 (1960-1970) (Zebra Press, Cape Town, 2004).

Smith, D.J., Young Mandela (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2010).

Strydom, L., Rivonia Unmasked (Voortrekkerpers, Johannesburg, 1965).

Volker, W., Army Signals in South Africa: The Story of the South African Corps of Signals and its Antecedents (Veritas Books, Pretoria, 2010).

Volker, W., Signal Units of the South African Corps of Signals and related Services (Veritas Books, Pretoria, 2010).

Wright, P., Spy Catcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer (Heinemann, Melbourne, 1987).

Footnotes

- D. Goldberg, The Mission: A Life for Freedom in South Africa (STE Publishers,

Johannesburg, 2010), p 99. ↩︎ - Liliesleaf Archives, Rivonia (hereafter LL), INT 2, Interview with Denis Goldberg,

conducted by G. Benneyworth, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎ - LL, INT 2, Interview with Denis Goldberg, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- L. Bernstein, Memory against Forgetting (Penguin, London, 1999), p 249. ↩︎

- LL, INT 4, Interview with Ahmed Kathrada, conducted by G. Benneyworth, Liliesleaf,

2005. ↩︎ - Much of the literature (for example Ellis), has it that Arthur Goldreich was the owner

of Liliesleaf farm. See S. Ellis, External Mission the ANC in Exile (Jonathan Ball,

Johannesburg, 2012), p 33. Goldreich was the nominal tenant who rented the property

from Navian Ltd. The lease was drawn up by R Sepel. See LL, G. Benneyworth of Site

Solutions© “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered – Rivonia Recovered” (All Rights

Reserved, Site SolutionsTM), pp 40–41. ↩︎ - LL, INT 6, LOT 2 (a-k), Interview with Vivien Ezra, conducted by G. Benneyworth,

Liliesleaf, 2006; LL, G. Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, p 137. ↩︎ - N.R. Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom (Abacus, London, 1994), pp 372–373 ↩︎

- Bernstein, Memory against Forgetting, p 254. ↩︎

- A. Kathrada, Memoirs (Zebra Press, Paarl, 2004), p 156 ↩︎

- LL, INT 3, LOT 4, Notes 1, Interview with Bob Hepple, conducted by G. Benneyworth,

Cambridge, 2005. ↩︎ - SADET, The Road to Democracy in South Africa, Volume 1 (1960–1970) (Zebra Press,

Cape Town, 2004), p 142. ↩︎ - LL, INT 2, Interview with Ahmed Kathrada, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- L. Strydom, Rivonia Unmasked (Voortrekkerpers, Johannesburg, 1965), pp 17–19. ↩︎

- G. Frankel, Rivonia’s Children (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1999), p 29. ↩︎

- Frankel, Rivonia’s Children, p 25. ↩︎

- D.J. Smith, Young Mandela (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2010), p 276. ↩︎

- M. Dingake, Better to Die on One’s Feet (South African History Online, Cape Town, 2015),

pp 67–69. ↩︎ - LL, Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, pp 142–143. ↩︎

- National Archives of South Africa (hereafter NASA), NAN 52, Box 8, MS 385.23, George

Mellis, Statement, 5 August 1963. ↩︎ - NASA, NAN 52, Box 8, Vol. MS. 385.23, George Mellis, Statement, 5 August 1963. ↩︎

- NASA, NAN 52, Box 8, MS 385.23, Sgt Christiaan Fourie, Station Commander Rivonia,

Statement, 23 September 1963. ↩︎ - LL, Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, Appendix C, Interview with

Gerhard Ludi. ↩︎ - LL, Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, Appendix C, Interview with

Gerhard Ludi. ↩︎ - LL, Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, Appendix C, Interview with

Gerhard Ludi. ↩︎ - NASA, BLM, Box 22, Vol. 2, File 442. ↩︎

- National Archives of the United Kingdom (hereafter NAUK), DO 195, 2, SECRET,

“Ghana’s Relations with the Union of SA”, 29 July 1960–1962. ↩︎ - LL, Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, Appendix C, Interview with

Gerhard Ludi. ↩︎ - LL, Benneyworth, “Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, Appendix C, Interview with

Gerhard Ludi. ↩︎ - W. Volker, Army Signals in South Africa: The Story of the South African Corps of Signals

and its Antecedents (Veritas Books, Pretoria, 2010), pp 226–227. ↩︎ - Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 227. ↩︎

- Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 227. ↩︎

- Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 228. ↩︎

- Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 229. ↩︎

- P. Wright, Spy Catcher: The Candid Autobiography of a Senior Intelligence Officer,

(Heinemann, Melbourne, 1987), p 154. ↩︎ - W. Volker, Signal Units of the South African Corps of Signals and Related Services (Veritas

Books, Pretoria, 2010), p 534. ↩︎ - Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 534. ↩︎

- Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 534. ↩︎

- Volker, Army Signals in South Africa, p 534. ↩︎

- Gavin Olivier, discussions with the author, 2005 and 2006; and LL, Benneyworth,

“Research Report: Rivonia Uncovered”, pp 144–145. ↩︎ - Paul Goldreich, email to author, 11 March 2007. ↩︎

- LL, INT 2, Interview with Denis Goldberg, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- Anonymous source. ↩︎

- Department of Land Affairs, Surveyor General, Mowbray, Cape Town South Africa, copy

of original contact sheets, 1961–1964, as obtained in 2004. ↩︎ - This article is available on the website of the contemporary South African Air Force at

http://www.saairforce.co.za/the-airforce/aircraft/60/shackleton-mr-3 Accessed 12

December 2016. ↩︎ - This website article focuses on Dassault Mirage jet aircraft for Microsoft Flight

Simulator and Combat Flight Simulator. At http://www.mirage4fs.com/slides15.html.

Accessed 12 December 2016. ↩︎ - See http://www.saairforce.co.za/the-airforce/aircraft/28/canberra-bi12 Accessed 12

December 2016. ↩︎ - Goldberg, The Mission, pp 109–110. ↩︎

- LL, INT 2, Interview with Denis Goldberg, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- Goldberg, The Mission, p 109. ↩︎

- LL, INT 2, Interview with Denis Goldberg, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- Kathrada, Memoirs, p 156. ↩︎

- SADET, The Road to Democracy in South Africa, Volume 1 (1960-1970), p 142. ↩︎

- LL, INT 3, LOT 4, Notes 1, Interview with Bob Hepple, Cambridge, 2005. ↩︎

- B, Hepple, Young Man with the Red Tie: A Memoir of Mandela and the Failed Revolution,

1960–1963, at https://www.amazon.com/Young-Man-Red-Tie-Revolution-ebook/dp/

B00EZM7PUW/ref=mt_kindle?_encoding=UTF8&me Accessed 24 March 2017. ↩︎ - LL, INT 3, LOT 4, Notes 1, Interview with Bob Hepple, Cambridge, 2005 ↩︎

- LL, INT 3, LOT 4, Notes 1, Interview with Bob Hepple, Cambridge, 2005. ↩︎

- LL, INT 2, Interview with Denis Goldberg, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- NASA, NAN 52, Box 8, MS 385.23, Detective Warrant Officer C.J. Dirker, Statement, 12

August 1963. ↩︎ - LL, INT 2, Interview with Arthur Goldreich, conducted by G. Benneyworth, Liliesleaf,

2004. ↩︎ - LL, INT 2, Interview with Arthur Goldreich, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- LL, INT 2, Interview with Arthur Goldreich, Liliesleaf, 2004. ↩︎

- Kathrada, Memoirs, p 161. ↩︎