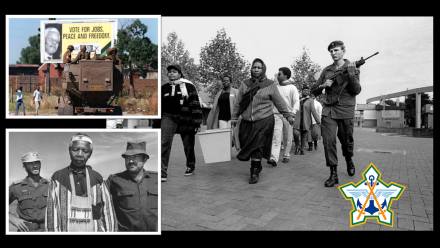

Here is an unusual ‘hero of the struggle for democracy in South Africa’. This is a South African Defence Force (SADF) former ‘whites only’ National Service conscript turned ‘volunteer’ holding a R4 assault rifle as he safely escorts the ballot boxes to a counting station during South Africa’s landmark 1994 election.

He, like thousands of other old SADF white National Servicemen literally volunteered over the transition between 1990 and 1994 to bring democracy to all South Africans and make the elections a reality. For good reason to, even on the election day itself bomb attacks where still going on and lives were still under threat. Yet now these military ‘heroes’ are conveniently forgotten or vanquished and rather inappropriately branded as “racists” by a brainwashed South African public that has lost perspective.

This is their story and it needs to be told. 1990 was a significant year – Apartheid in all its legal forms was removed from the law books, the system that had generated ‘the struggle’ was dead. The African National Congress (ANC) was also officially unbanned in February 1990, unhindered to practice its politics. All that remained was a period of peaceful negotiation and reconciliation … the future looked bright. But did that happen?

Unfortunately not, all hell broke out and the organisations that ultimately kept the peace were the statute armed forces of South Africa (SADF and SAP), who by default steered the country safely on the path to democracy in its final course up to and through the 1994 elections, and not the ‘struggle heroes’ of the ANC, who it can really be said to have stumbled at the last hurdle.

It’s a pity as without this stumble the ANC could truly claim the mantle of the “liberators” who brought democracy to all South Africans but now, rather inconveniently for them, they have to share it with the SADF – and in addition to SADF professional soldiers a huge debt gratitude is owed by the country to the old white SADF National Servicemen – the ‘conscripts’.

The violence of the ‘Peace’ Negotiations

In 1990, once unbanned the ANC immediately went into armed conflict with all the other South Africans who did not favourably agree with them – especially the Zulu ’s political representation at the time – the Inkata Freedom Party (IFP), but also other ‘Black’ liberation movements such as AZAPO (Azanian Peoples Organisation) and the old ‘homeland’ governments and their supporters. Instead of taking up a role of actively peacekeeping to keep the country on the peace negotiation track, they nearly drew South Africa into full-blown war.

From 1990 to 1994 South Africa saw more violence than the entire preceding period of actual “Apartheid”. There was extensive violence and thousands of deaths in the run-up to the first non-racial elections in South Africa in April 1994 – and to be fair it was not just the ANC , the violence was driven by a number of political parties left and right of the political spectrum as they jostled for political power in the power vacuum created by CODESA negotiations.

To deal with this escalation of all out political violence, the SADF called out for an urgent boost in resources, however conscription was unravelling and numbers dropping off rapidly from the national service pool. Luckily however, tens of thousands of ‘white’ ex National servicemen were now serving out ‘camp’ commitments in various Citizen Force units, SADF Regiments and in the Regional Commando structures who heeded the call and volunteered to stay on – fully dedicated to serving the country above all else, and fully committed to keep the country on the peace process track and stop the country sliding into civil war.

In an odd sense, if you really think about it, these white conscripts are the real ‘heroes’ that paved the way for peace. For four full years of political vacuum they literally risked their lives by getting into harms way between the various warring protagonists, left/right white/black – ANC, IFP, PAC and even the AWB – and it cannot be underestimated the degree to which they prevented an all out war from 1991 to 1994 whilst keeping the peace negotiations on track to a fully democratic settlement.

That South Africa enjoys the fruits of the CODESA democratic process, without plunging itself into civil war whilst democracy was negotiated is very much directly attributed to the men and women in the SADF.

The white supremacist uprising

In 1991, the armed insurrection in South Africa became more complex when far right-wing ‘white supremacist’ break-away groups such as the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) began to increasing turn to armed violence to further their cause. South Africa’s Defence Force and Police structures and personnel now also had to deal with this added, rather violent, dynamic to an already feuding and violent ethnic and political landscape.

‘White’ loyalties where quickly cleared up between white right wingers and white members of the statute forces when the issue came to a head at ‘The battle of Ventersdorp’ on 9 August 1991. The statute force maintained the upper hand and in all, 3 AWB members and 1 passer-by were killed. 6 policemen, 13 AWB members and 29 civilians were injured in the clash.

In addition to Pretoria and surrounds, this right wing ‘revolution’ also focused on Bophuthatswana in 1994, The AWB attempted an armed Coup d’état (takeover by force of arms) after Bophuthatswana homeland’s President Mangope was overthrown by a popular revolt. In addition to the SADF, this uprising was also foiled by what remained of the statute forces of Bophuthatswana, and was to cumulate in the infamous shooting of 3 surrendered AWB members in front of the world’s media by a policeman.

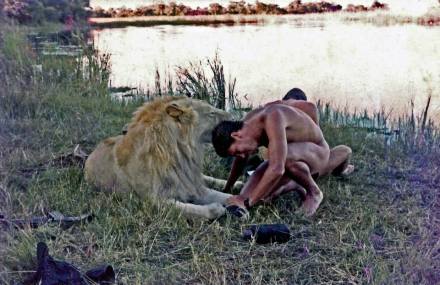

Luckily not part of this particular controversy, the SADF ‘national service’ soldiers were deployed into the region to quell the uprising and arrested looters in the chaos of the revolt stabilising the situation – as the below famous image taken in Mmabatho by Greg Marinovich shows.

The net result of all this is recorded as a “SADF victory, removal and abolition of Lucas Mangope’s regime, disestablishment of Bantustan”. In all, Volksfront: 1 killed, AWB: 4 killed, 3 wounded and Bophuthatswana’s mutineers suffered 50 dead, 285 wounded.

SADF members round up looters in Mafikeng during the attempted BDF uprising in 1994 and bring peace to the streets

The war between the ANC and IFP

To get an idea of this low-level war between the ANC and IFP for political control in Kwa-Zulu Natal alone, The Human Rights Committee (HRC) estimated that, between July 1990 and June 1993, an average of 101 people died per month in politically related incidents – a total of 3 653 deaths. In the period July 1993 to April 1994, conflict steadily intensified, so that by election month it was 2.5 times its previous levels.

Here SADF soldiers conduct a search through bush veld in KwaZulu Natal 1994 and keep a close eye on protesters with ‘traditional weapons’ – Section A KwaMashu Hostel, an Inkatha stronghold.

Moreover, political violence in this period extended to the PWV (Pretoria– Witwatersrand-Vereeniging) region in the Transvaal. The HRC estimated that between July 1990 and June 1993, some 4 756 people were killed in politically related violence in the PWV area. In the period immediately following the announcement of an election date, the death toll in the PWV region rose to four times its previous levels.

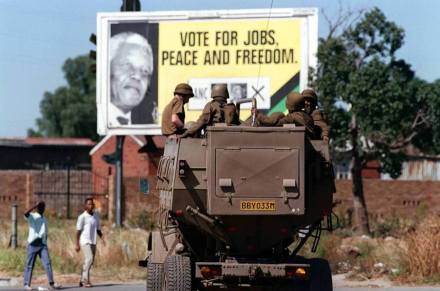

Here are SADF National Service soldiers on patrol in Soweto, South Africa, 1991/2 and keeping the peace in Bekkersdal in 1994.

Much of this climaxed into famous incident when the IFP chose to march in Johannesburg brandishing ‘traditional weapons’ in 1994. Outside the African National Congress (ANC) headquarters at ‘Shell House’ a shootout in downtown Johannesburg between the ANC and IFP supporters erupted.

Here in a famous photo taken by Greg Marinovich is a member of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) who lies dead, his shoes are taken off for the journey to the next life. These three SADF soldiers have come forward into the line of fire – strait between the two warring factions and are keeping the ANC gunmen at Shell House at bay preventing further loss of life, the another image shows a SADF medic coming to the assistance of a wounded IFP member at Shell House – the degree of the life changing injury of a bullet shattering his leg quite graphically evident.

Another good example is also seen here at Bekkersdal township, Transvaal, South Africa 1994. AZAPO supporters fire at ANC supporters in armed clashes between these two groups of the ‘liberation struggle’. The SADF again suppressed the clash, the next image shows heavy armed SADF National Servicemen in support by driving into the middle of the fray and keeping the belligerents apart – in effect saving lives.

Bigger clashes took place in KaZulu Natal – an example is seen here at KwaMashu in 1994. ANC militants with a home-made gun or ‘kwash’ do battle with Inkatha Freedom party supporters across the valley at Richmond Farm. Again SADF personnel were moved in to separate the protagonists, here 61 Mech National Servicemen in a SADF “Ratel” IFV patrol Section A, KwaMashu Hostel, an Inkatha stronghold.

In an even stranger twist, a blame game ensured with the ANC not blaming itself and instead accusing a ‘third force’ of guiding the violence and laid the blame on FW de Klerk. Funnily no evidence of a ‘third force’ has ever been found and the TRC hearings rejected the idea after a long investigation.

The 1994 Election ‘Call-Up’

In the lead-up to the elections in April 1994, on 24 August 1993 Minister of Defence Kobie Coetsee announced the end of ‘whites only’ conscription. In 1994 there would be no more call-ups for the one-year initial training. Although conscription was suspended it was not entirely abandoned, as the SADF Citizen Force and SADF Commando ‘camps’ system for fully trained conscripts remained place. Due to priorities facing the country, especially in stabilising the country ahead of the 1994 General Elections and the Peace Progress negotiations, the SADF still needed more strength to guard election booths and secure key installations.

So in 1994, the SADF called-up even more ‘white’ SADF Civilian force members, SADF Commando and SADF National Reservists to serve again, and despite the unravelling of conscription laws the response was highly positive with thousands of more national servicemen ‘voluntarily’ returning to service in order to safeguard the country into it’s new epoch.

National Reserve members were mustered at Group 18 outside Soweto in January 1994, some even arriving without uniform. As part of this mustering I even have the personal experience of asking one of them what happened to his equipment and uniform to which the reply was “burnt it after my camps, but for this I am prepared to serve my country again.” This comment says a lot as to devotion and commitment of someone making a difference at a turning point of history.

‘Camp’ call-ups and the call-up of ex-conscript SADF members on the National Reserve reached record proportions over the period of the April 1994 elections, and for the first time in history, in a strange twist of fate, the End Conscription Campaign( ECC) called these conscripts to consider these “election call-ups” to be different from previous call-ups and attend to their military duties.

It is highly ironic that even the ECC could see the necessity of security to deliver South Africa to democracy in this period – it was not going to come from the ‘liberation’ movements or any ‘cadres’ as they were part of the problem perpetuating the violent cycle in the power vacuum – it had to come from these SADF conscripts and statutory force members committed to their primary role of serving the country (and not a political ideology or party).

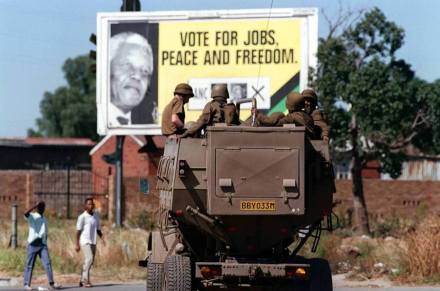

The threats on election day where very real – here South African Defence Force personnel cordon off a bomb blast area and South African police personnel inspect the bombing near the air terminals at Jan Smuts International Airport (now OR Tambo International). This was the final Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) cell attack on April 27, 1994 in response to the landmark election day held the same day.

While campaigning for the Presidency, even Nelson Mandela, seen here in traditional dress, made sure to stop and thank citizen force members of the SADF for their support and duty during South Africa’s first fully democratic election in 1994.

These ordinary South African servicemen showed what they are really made of by putting themselves in harm’s way to bring about the democracy that South Africans share today – they where literally the unsung heroes, and all respect to Nelson Mandela, he knew that and took time in his campaigning to recognise it – these men did not ask for much in return and this small recognition would have been enough.

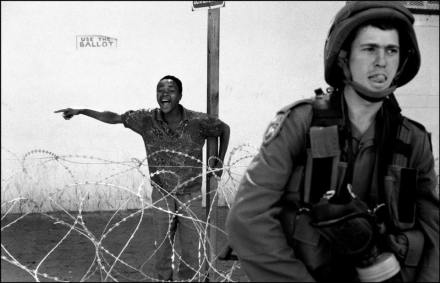

Here a SADF member keeps a guarding and secure eye whilst fellow South Africans are queuing to vote in the historic first democratic election on April 27, 1994. This election poll was in Lindelani, Kwa Zulu Natal. Nelson Mandela voted here at 6am and his car passed by as these youngsters sang to honour him.

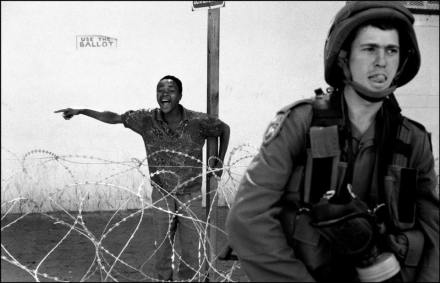

Another image shows a SADF National Serviceman guarding the election booths in Johannesburg, whilst a newly enfranchised South African eagerly points the way to the voting polls.

It was not just National Servicemen, all the uniformed men and women of the SADF and the SAP, of all ethnic groups in South Africa, paved the way for real peace when the country really stood at the edge and about to fall into the abyss of violence and destruction from 1990 to 1994.

This is an inconvenient truth – something kept away from the contemporary narrative of South Africa’s ‘Liberation’ and ‘Struggle’ – as it does not play to the current ANC political narrative. These men and women are now openly branded by lessor Politicians in sweeping statements as “Apartheid Forces” – demonised and vanquished – whereas, in reality nothing can be further from the truth. South Africans today – whether they realise it or not, owe these SADF Professionals and especially the former ‘whites only’ national service conscripts a deep debt of gratitude for their current democracy, civil rights and freedom.

In conclusion

If you had to summarise the military involvement in the transition period, it was the SADF – not the ‘Liberation’ armies of the ANC and PAC, who brought down civil revolts in all the ex-‘Bantustans’, it was the SADF that suppressed an armed right-wing revolutionary takeover in South Africa , it was the SADF that put itself into harms way between all the warring political parties in the townships all over the country and literally saved thousands of lives for 4 long years and it was the SADF who stood guard and secured the 1994 election itself – in this sense it was the SADF (and especially the ‘ex’ white conscripts) who practically delivered the instrument of full democracy and freedom safely to all the citizens of South Africans so they could in fact vote in the first place (without fear of being blown up or shot to pieces in the voting booths) – and that’s a fact and there’s no changing it.

The SADF veterans by far make up the majority of South Africa’s military veteran community, they also fought for liberation and peace, and as they say whenever current South African politicians idealise the MK veterans and demonise the old pre 94 SADF veterans all I can say is – “please don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story” and the inconvenient fact is the ‘old’ SADF delivered the ‘Instrument’ of democracy, not MK.

Related Work and Links

Real Heroes; Tainted “Military Heroes” vs. Real Military Heroes

Conscription; Conscription in the SADF and the ‘End Conscription Campaign’

Article researched and written by Peter Dickens.

Photo copyrights to Greg Marinovich and Ian Berry. Feature image photograph copyright Paul Weinberg

2 SAI was established on January 1, 1962, at Walvis Bay, at the time an enclave of South African territory, surrounded by South West Africa (Namibia). It was about the most furthest and remote training base to get a call-up from, a conscript here was truly a ‘long way from home’.

2 SAI was established on January 1, 1962, at Walvis Bay, at the time an enclave of South African territory, surrounded by South West Africa (Namibia). It was about the most furthest and remote training base to get a call-up from, a conscript here was truly a ‘long way from home’.