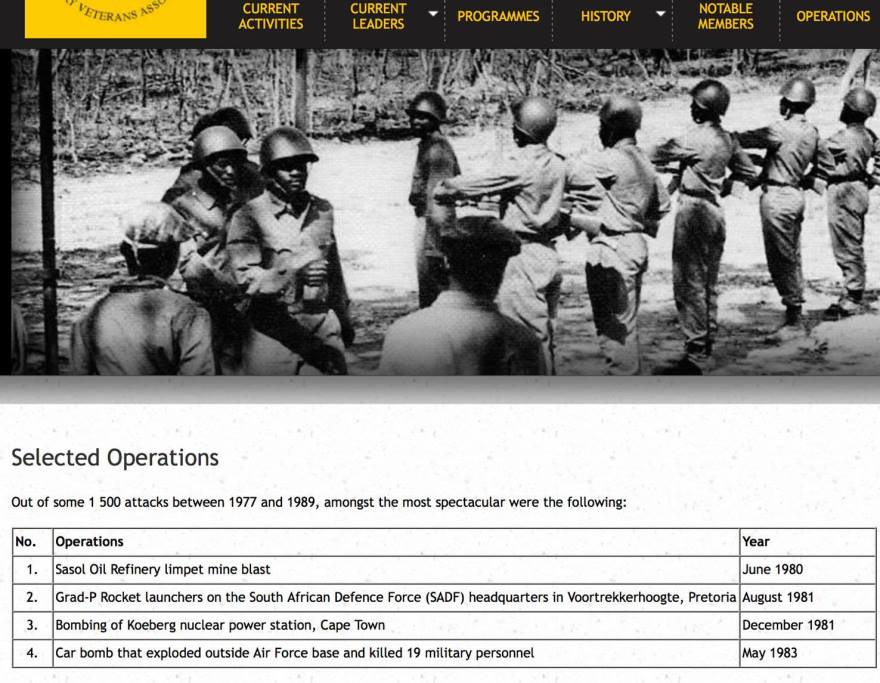

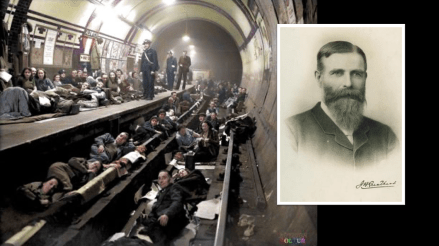

Whilst researching Umkhonto we sizwe (MK) actions against the SADF, I took to the MK Veterans association webpage. Their ‘operations list’ section pulls up a section on attacks they (MK) wish to highlight as significant military achievements .

It states; “Out of some 1500 attacks between 1977 and 1989, amongst the most spectacular were the following:

1. June 1980 – Sasol Oil Refinery limpet mine blast

2. December 1981 – Bombing of Koeberg Nuclear Power station

3. May 1983 – Car bomb outside Air Force base and killed 19

4. August 1981 – Grad-P Rocket launchers on the South African Defence Force (SADF) headquarters in Voortrekkerhoogte, Pretoria”

Stop the PRESS!

I am all for credit were credit is due for great or significant military deeds and actions (this blog is dedicated to them). But I also like to put things into context, the Sasol limped mine attack was pretty “spectacular,” 8 fuel tanks were blown up causing damage estimated at R66 million – I’ll give them that one.

Koeberg Nuclear Station attack. Yes, “Spectacular” enough, 4 bombs went off, nobody was killed, one of the buildings bombed was for radioactive nuclear waste and was not yet on-line and under construction. A very effective message sent to the SADF’s nuclear weapons program, so “spectacular” – I’ll give them that one too.

As to the bombing of the SAAF ‘Air Force Base’, lets put this one into context as the statement is misleading. The SAAF administrative offices targeted were inside the Nedbank Plaza Building in Pretoria (shared with Nedbank and the Dutch embassy) and not a stand-alone heavily guarded “Air Force base” (those bases were in Voortrekkerhoogste). The bomb was set off in a public road ‘Church Street’ outside Nedbank Plaza. As a result I would not put the tag “spectacular” on it – ‘tragic’ and ‘deadly’ yes, because of the aftermath, of the 19 killed: 2 of them were MK operators themselves (‘blue on blue), 7 SAAF members and 10 civilians. 217 people were wounded, most of them civilians. It’s the biggest ‘feather’ in the MK military achievement cap by far – but it remains a very ‘innocent’ blood soaked and controversial one no matter how you try and spin it.

Now, this last “spectacular” attack caught my eye “Grad-P Rocket launchers on the South African Defence Force (SADF) headquarters in Voortrekkerhoogte, Pretoria”. Because during my National Service training as a candidate officer at Personnel Services army base situated in Voortrekkerhoogte there was a base story about an attack which left unexploded mortars bouncing off the base’s barracks roofs. So I took to investigating it.

Here’s the report from the Truth and Reconciliation Hearing – and I would ask readers to focus their minds on how ‘spectacular’ it is.

The Attack on Voortrekkerhoogste military installations: August 1981

This attack took place on 12 August 1981.

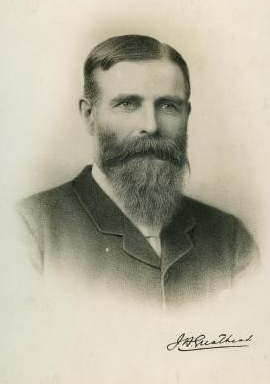

Barney Molokoane

Voortrekkerhoogte was the main command base of the South African Army. The initial reconnaissance was carried out by two ANC supporters from Europe, namely Klaas de Jonge and Helene Pastoors. A smallholding which was to be used as the base for the operation was rented at Broederstroom. Thereafter the commander of the unit which was to carry out the operation, Barney Molokoane, was infiltrated into the country.

He selected the site from which the rockets used in the attack would be launched. The material to be used in the attack was then brought into the country from Swaziland and cached on the smallholding. The remaining members of the unit were then infiltrated into the country. They were Sidney Sibepe, Vuyisile Matroos, Johannes Mnisi, Vicks and Philemon Malefo.

The unit proceeded to the operational site, which was approximately four kilometres away from Voortrekkerhoogte and fired their rockets at the target. A GRAD-P rocket launcher was used to fire the rockets. However, as they were doing this a crowd gathered to watch them. Philemon Malefo, who was in the getaway vehicle, drove off in order not to be exposed. The unit leader, Barney Molokoane and others then attempted to get an alternative vehicle in nearby Laudium and in so doing a man was shot and injured. The unit members then successfully withdrew from the scene.

The rockets struck in Voortrekkerhoogte and the attack resulted in minor injuries to one woman.

Truth and Reconciliation Amnesty Hearing – January 2000

In reality

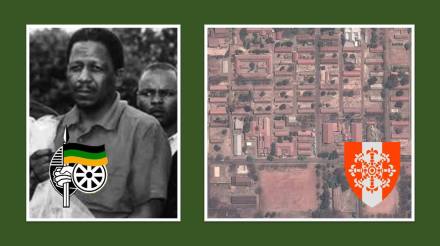

The attack was launched from a nearby koppie, the rockets (or bombs) launched were ineffectual, no substantial damage whatsoever. If the base story is to be believed most of them were launched towards the SADF’s Personnel Services School (known as PSC or PDK in Afrikaans), located in the centre of the Voortrekkerhoogte complex. It has the Army College opposite it and Technical Services School, Military Hospital, Maintenance Services School and the Provost School nearby it as well as a civilian managed supermarket and petrol station next to it. As ‘schools’ almost all of them are training bases.

The “main command base for the SADF’ they were not. That command base was located in an underground ‘nuclear proof’ building behind the Pretoria Jail called ‘Blenny’ and it housed “D Ops” – Directive Operations (and its located quite a distance from central Voortrekkerhoogte).

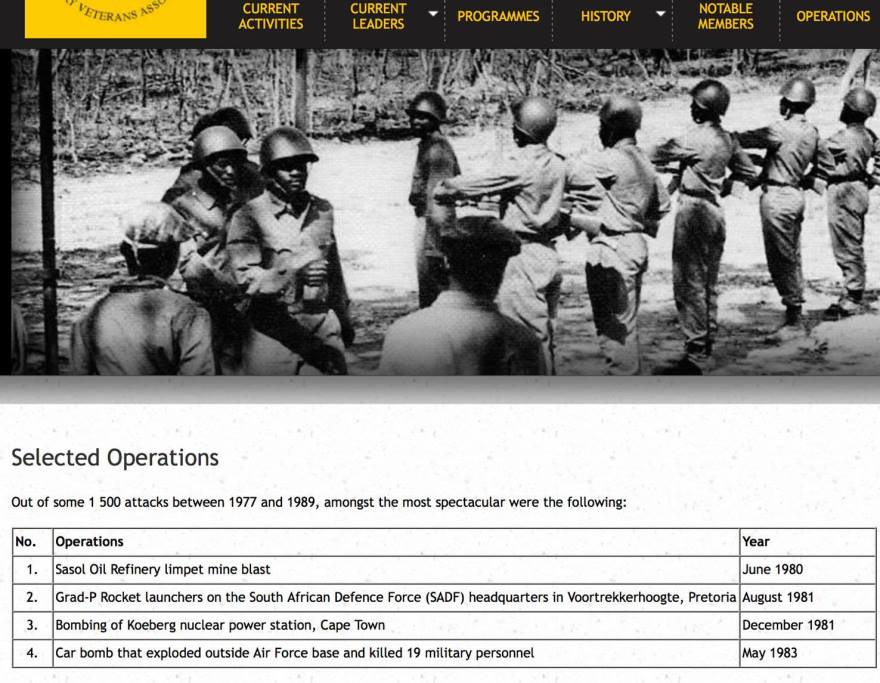

The Soviet era GRAD-P portable rocket system uses a monotube and fires 122 mm high-explosive fragmentation rockets (which arm themselves in flight). This system is highly effective, accurate enough and delivers on some very devastating results (with a very good impact radius) – deadly to both buildings and people. In essence it’s ‘one’ tube of the GRAD multiple rocket launch platform. For this reason it is loved by terrorist, paramilitary and guerrilla forces the world over – usually mounted on small trucks or large pick-up vehicles (known as ‘technicals’). It’s robust, simple and highly effective. It also makes a very big ‘bang’.

The Soviet era GRAD-P portable rocket system uses a monotube and fires 122 mm high-explosive fragmentation rockets (which arm themselves in flight). This system is highly effective, accurate enough and delivers on some very devastating results (with a very good impact radius) – deadly to both buildings and people. In essence it’s ‘one’ tube of the GRAD multiple rocket launch platform. For this reason it is loved by terrorist, paramilitary and guerrilla forces the world over – usually mounted on small trucks or large pick-up vehicles (known as ‘technicals’). It’s robust, simple and highly effective. It also makes a very big ‘bang’.

So I can’t possibly understand why this attack did not deliver on the ‘Big Bang’ this weapon is famed for, nor is there much recollection of the type of ‘loud’ and ‘devastating’ effects this system has – all launch variants of the GRAD scare the living wits out of anyone anywhere near it – from the firing position to the target, and it was reported as fired into a very populated area bustling with thousands of troops undergoing training and civilians.

Also, where is this weapon system now? It is certainly not on display at any military or ‘Apartheid Struggle’ museum that I am aware of, there are very few significant military ‘artefacts’ of the MK ‘struggle’ as it is, and as this attack is regarded as one of their key successes, so it carries with it some historical value. All Soviet weapons captured at the time by the SADF are now at the disposal of the ANC government, or they are still in possession of some ANC members not willing to give them up – very little of the total arms cache’ of weapons smuggled into the Republic by MK have ever been declared (in fact in the early 90’s much of it fell into the ‘black market’ and into criminal’s hands when many MK Cadres demanded and did not receive remuneration and the free houses they were promised when joining and fighting for MK).

Maybe the fuses were set to the wrong distances maybe its an issue of operator capability and training, maybe it was badly aimed? Don’t know, maybe MK are confusing the GRAD-P with a small portable mortar system instead – the GRAD-P tube is a very big section of kit and does not ‘break down’ to fit into an average civilian vehicle, nor do the rockets themselves – especially in one already full of men trying to be inconspicuous in a populated area – have a look at the image below of a IS terrorist cell launching a GRAD-P and you’ll see what I mean. Who knows, far too many unanswered questions.

In any event, there was an MK attack of some sort using either rockets or mortars on bases in Voortrekkerhoogte – that part is true (the Apartheid ‘state’ secret apparatus even retaliated the attack by covertly bombing the ANC offices in London – because of the ‘British connection’ in the assault on Voortrekkerhoogte).

However, the results speak for themselves. No significant military buildings were damaged, some accounts recall one of the bombs/rockets falling on the parade ground of the Army College, other accounts report one bomb/rocket hitting an empty bungalow at PD School (this building was destroyed), whilst another account states one more bomb/rocket bounced off another PD School bungalow roof and did not explode. Some recall that another bomb/rocket hit a toilet block at the PTI section of Army College and another landed on Northern Transvaal Command’s lawn.

PSC (L) and Army College (R)

There are no accounts of wide-spread panic around Voortrekkerhoogte (military or public) from a GRAD-P rocketing, no large media flurry (It was reported in local papers, but there was no large scale media pursuit), there were no SADF casualties (injuries or deaths) and the casualties were in fact two civilians. One female civilian domestic employee who was down-range of the launch, she was living in a room adjacent to an SADF officers house, her living quarters were hit, however she received only a minor injury, The second civilian injured was up-range of the launch, who (lets face facts) was shot and injured in a car hijacking caused by a botched getaway plan, when their MK driver got scared and ‘scarpered’ off with their vehicle.

‘Spectacular’ it is was not.

How much is fact and how much is hype?

Because the record on the MK vets website seemed a little inflated, misleading and incomplete to me, I took to checking the 1500 other claimed attacks to see how many of them were against the SADF itself – force to force so to speak (apples to apples). The only effective attack against the ‘SADF’ on the list other than the attack on the Nedbank Plaza in Church Street housing the SAAF offices was the Wit Command bombing, which resulted in 25 injuries and structural damage to a military base building (the drill hall), but luckily nobody died – it was also a ‘one man op’ carried out by a ‘white Afrikaner’ ironically (see The truth behind the bombing of Witwatersrand Command).

There is probably good reason that the MK list only 4 highlights (followed by a sweeping claim of thousands of attacks), as simply put, there are not many more ‘spectacular’ highlights at all. The rest of the attacks on the SADF by MK were simply not effectual and did not meet any significant objective. There was a bomb attack on a Citizen Force Regiment’s car park – The Kafferian Rifles (but no information to back it), two bomb blasts in SADF Recruitment offices open to the public (no injuries and minor building damage), an attack on an outlying SADF Radio communications post, with no damage or injuries, a foiled bomb attack on a Wit Command medic post (no damage or injuries) and a bomb which went off in a dustbin outside Natal Command (no damage or injuries). That’s it.

The only other related attack was more ‘soft’ civilian than ‘hard’ military target, this was the bombing of The Southern Cross Fund offices. Luckily no injuries or deaths, just building damage – as many may recall The Southern Cross Fund was a civilian driven charity which collected Christmas presents and the like to support troop morale in the SADF, a very ‘soft’ target indeed.

There were also some MK claims to the TRC as to numerous SADF personnel killed in armed MK skirmishes with SADF patrols on the Botswana border. However I checked the dates against the Honour Roll and the military record of SADF deaths and operation reports and I came up with nothing – no SADF bodies in evidence to the claims on the dates specified to the TRC by MK. I also checked the SADF veterans social forums on-line and nobody had any recollection of these attacks (nor do many of them even recall this ‘spectacular’ attack on Voortrekkerhoogte). It stands as an odd testimony that there is literally not one proper ‘war story’ of the SADF engaging MK combatants by literally thousands of SADF veterans now recounting their time in the SADF and freely publishing papers, on-line stories (across a variety of portals), their diaries and even books on their experience. Maybe the MK is confusing the South African Defence Force (SADF) with The South African Police (SAP), who knows.

On platforms such as Wiki, MK is listed as one of the belligerents in the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale, however if you ask any old SADF veteran if they saw any MK combatant and engaged them during the entire duration of the Border war from 1966 to 1989 (or even at the Battles on the Lomba and at Cuito Cuanavale specifically), they will say no, not one – SWAPO, MPLA, Cubans and even Russian combatants – yes, they saw a great many of these.

In line with the old SADF veterans testimony, there is some truth to it, there is not one recorded attack by MK of an MK unit, section/platoon strength and above, on any SADF personnel, armour or installation during the entire Border war.

All the other quoted attacks were stated as been on the South African Police and Police stations, not the SADF, and access to this record is not easy and not of concern as I was looking into the SADF only so as to record actions against the actual military by another military outfit.

In conclusion

What it does say, is that for the most part the SADF were unmoved by any actions by the MK, it certainly did not change their mode of operation in the Republic itself, nor were they overly fearful of MK attacks. The bases remained relatively lightly guarded in terms of ‘operational readiness,’ usually by National Servicemen bored out of their minds with only 5 rounds in one magazine (not inserted) – as was the regulation on many bases (the SADF bases in South West Africa/Namibia – different story – there was a proper war on in Namibia against SWAPO, the MPLA and Cuba, in response SADF personnel on base were armed to the teeth). Unarmed and uniformed SADF National Servicemen were to be found in their thousands roaming relatively safely all over the Republic on weekend passes. The SADF was even confident enough that any internal violence generated by MK (and other liberation movements) could be curtailed by the South African Police (primarily) that they even reduced military conscription to just one year when the Border War with SWA/Angola concluded in 1989 – reducing SADF manpower and ‘operational readiness’ in the Republic even more.

What this record and new hype around MK also shows is a gradual ‘inflation’ of ‘combat prowess’ and the heroic deeds of men in MK, now so revered as national heroes and positioned as ‘war heroes’ with a combat record to be reckoned with. Whilst the SADF and its very solid combat record has been demonized and vanquished. There is some truth, to many in South Africa now (especially the youth) that MK played a role in standing up against Apartheid, and we can’t take that from them – they did, so they are idolised by many, that’s a fact. But we need to scrutinise the historical record (the hard facts) in all this hyper-admiration of MK.

Where the ANC were successful, lies less in any great military mission by MK and more in making the old ‘black’ townships of South Africa ungovernable by the use of simple ‘civil dissonance’ – here they were ‘spectacularly’ successful. It was this deepened civil unrest and broader political violence on a grassroots level that brought all the significant pressure on Apartheid South Africa.

Militarily speaking it’s an ‘inconvenient’ fact that South Africa did not have an armed insurrection anything like those initiated by other ‘liberation armies’ in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Mozambique, Angola and South West Africa (Namibia). Unlike these countries, South Africa is a little different, as at no point were armed MK cadres tested in a conventional military battle scenario against armed SADF soldiers – that never happened. So as time moves on and memories fade we need to keep perspective, no matter how inconvenient.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References: South African History On Line. ANC Umkhonto we sizwe Veteran Association website. Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Wikipedia.

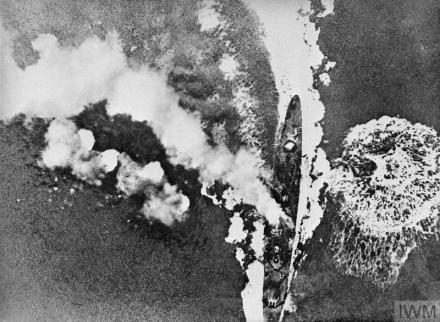

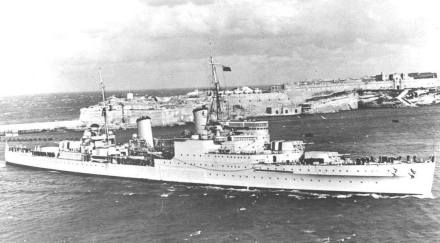

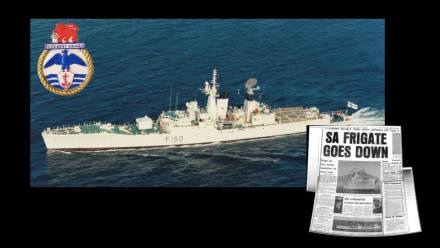

Gloucester was nicknamed The Fighting G and saw heavy service in the early years of World War II. The ship was deployed initially to the Indian Ocean and later South Africa before joining Vice Admiral Cunningham’s Mediterranean fleet in 1940. She was sunk on 22 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete with the loss of 722 men out of a crew of 807.

Gloucester was nicknamed The Fighting G and saw heavy service in the early years of World War II. The ship was deployed initially to the Indian Ocean and later South Africa before joining Vice Admiral Cunningham’s Mediterranean fleet in 1940. She was sunk on 22 May 1941 during the Battle of Crete with the loss of 722 men out of a crew of 807. After German paratroopers landed on Crete on 20 May, the cruiser HMS Gloucester was assigned to Force C that was tasked with interdicting any efforts to reinforce the German forces on the island. On 22 May, while in the Kythria Strait about 14 miles (12 nmi; 23 km) north of Crete, she was attacked by German “Stuka”s of StG 2 shortly before 14:00, together with the light cruiser HMS Fiji and the destroyer HMS Greyhound. The Greyhound was sunk and the two cruisers were each hit by 250-kilogramme bombs, but not seriously damaged. Two other destroyers were ordered to recover the survivors while the two cruisers covered the rescue efforts. Gloucester was attacked almost immediately and sustained three more hits and three near-misses and sank. Of the 807 men aboard at the time of her sinking, only 85 survived. Her sinking is considered to be one of Britain’s worst wartime naval disasters.

After German paratroopers landed on Crete on 20 May, the cruiser HMS Gloucester was assigned to Force C that was tasked with interdicting any efforts to reinforce the German forces on the island. On 22 May, while in the Kythria Strait about 14 miles (12 nmi; 23 km) north of Crete, she was attacked by German “Stuka”s of StG 2 shortly before 14:00, together with the light cruiser HMS Fiji and the destroyer HMS Greyhound. The Greyhound was sunk and the two cruisers were each hit by 250-kilogramme bombs, but not seriously damaged. Two other destroyers were ordered to recover the survivors while the two cruisers covered the rescue efforts. Gloucester was attacked almost immediately and sustained three more hits and three near-misses and sank. Of the 807 men aboard at the time of her sinking, only 85 survived. Her sinking is considered to be one of Britain’s worst wartime naval disasters. ALLISON, Oswald H, Able Seaman RNVR, 67349 (SANF), killed

ALLISON, Oswald H, Able Seaman RNVR, 67349 (SANF), killed

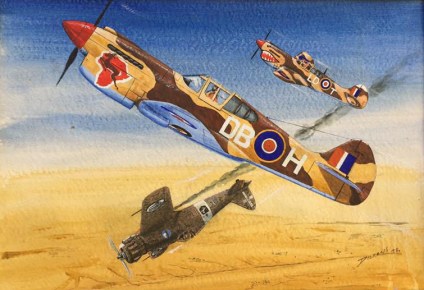

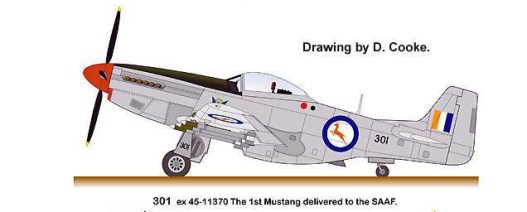

74 Squadron was formed during World War 1,Its first operational fighters were S.E. 5as in March 1918, and served in France until February 1919, during this time it gained a fearsome reputation and was credited with 140 enemy planes destroyed and 85 driven down out of control, for 225 victories. No fewer than Seventeen aces had served in the squadron, including one Victoria Cross Winner Major Edward Mannock. In this line up of aces was one notable South African, and this man came from Kimberley, Capt. Andrew Cameron Kiddie DFC, and he came from unassuming beginnings – he was one of Kimberley’s local bakers.

74 Squadron was formed during World War 1,Its first operational fighters were S.E. 5as in March 1918, and served in France until February 1919, during this time it gained a fearsome reputation and was credited with 140 enemy planes destroyed and 85 driven down out of control, for 225 victories. No fewer than Seventeen aces had served in the squadron, including one Victoria Cross Winner Major Edward Mannock. In this line up of aces was one notable South African, and this man came from Kimberley, Capt. Andrew Cameron Kiddie DFC, and he came from unassuming beginnings – he was one of Kimberley’s local bakers.

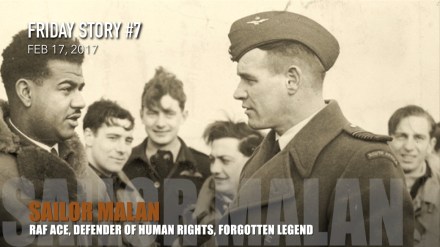

World War 2 would shape 74 Squadron as one of the best in The Royal Air Force. It became the front-line squadron which took the brunt of the attacks during The Battle of Britain, and this time the squadron was commanded by a formidable South African, Group Captain A G ‘Sailor’ Malan DSO & Bar DFC & Bar.

World War 2 would shape 74 Squadron as one of the best in The Royal Air Force. It became the front-line squadron which took the brunt of the attacks during The Battle of Britain, and this time the squadron was commanded by a formidable South African, Group Captain A G ‘Sailor’ Malan DSO & Bar DFC & Bar.

Air Vice-Marshal John Howe was one of the RAF’s most experienced and capable Cold War fighter pilots, whose flying career spanned Korean war piston-engined aircraft to the supersonic Lightning and Phantom.

Air Vice-Marshal John Howe was one of the RAF’s most experienced and capable Cold War fighter pilots, whose flying career spanned Korean war piston-engined aircraft to the supersonic Lightning and Phantom.

In retirement he was a sheep farmer in Norfolk, where he was known as the “supersonic shepherd”; he retired in 2004. He was a capable skier and a devoted chairman of the Combined Services Skiing Association. A biography of him, Upward and Onward, by Bob Cossey, was published in 2008. John Howe married Annabelle Gowing in March 1961; she and their three daughters survive him.

In retirement he was a sheep farmer in Norfolk, where he was known as the “supersonic shepherd”; he retired in 2004. He was a capable skier and a devoted chairman of the Combined Services Skiing Association. A biography of him, Upward and Onward, by Bob Cossey, was published in 2008. John Howe married Annabelle Gowing in March 1961; she and their three daughters survive him.

This time Sailor’s legacy has been carried forward by “Inherit South Africa” in this excellent short biography narrated and produced by Michael Charton as one of his Friday Stories – this one titled FRIDAY STORY #7: Sailor Malan: Fighter Pilot. Defender of human rights. Legend.

This time Sailor’s legacy has been carried forward by “Inherit South Africa” in this excellent short biography narrated and produced by Michael Charton as one of his Friday Stories – this one titled FRIDAY STORY #7: Sailor Malan: Fighter Pilot. Defender of human rights. Legend.

submarine when it has surfaced. It is a true statement of South African heritage, and what better way to wish all South Africans a ‘Happy

submarine when it has surfaced. It is a true statement of South African heritage, and what better way to wish all South Africans a ‘Happy

The Soviet era GRAD-P portable rocket system uses a monotube and fires 122 mm high-explosive fragmentation rockets (which arm themselves in flight). This system is highly effective, accurate enough and delivers on some very devastating results (with a very good impact radius) – deadly to both buildings and people. In essence it’s ‘one’ tube of the GRAD multiple rocket launch platform. For this reason it is loved by terrorist, paramilitary and guerrilla forces the world over – usually mounted on small trucks or large pick-up vehicles (known as ‘technicals’). It’s robust, simple and highly effective. It also makes a very big ‘bang’.

The Soviet era GRAD-P portable rocket system uses a monotube and fires 122 mm high-explosive fragmentation rockets (which arm themselves in flight). This system is highly effective, accurate enough and delivers on some very devastating results (with a very good impact radius) – deadly to both buildings and people. In essence it’s ‘one’ tube of the GRAD multiple rocket launch platform. For this reason it is loved by terrorist, paramilitary and guerrilla forces the world over – usually mounted on small trucks or large pick-up vehicles (known as ‘technicals’). It’s robust, simple and highly effective. It also makes a very big ‘bang’.

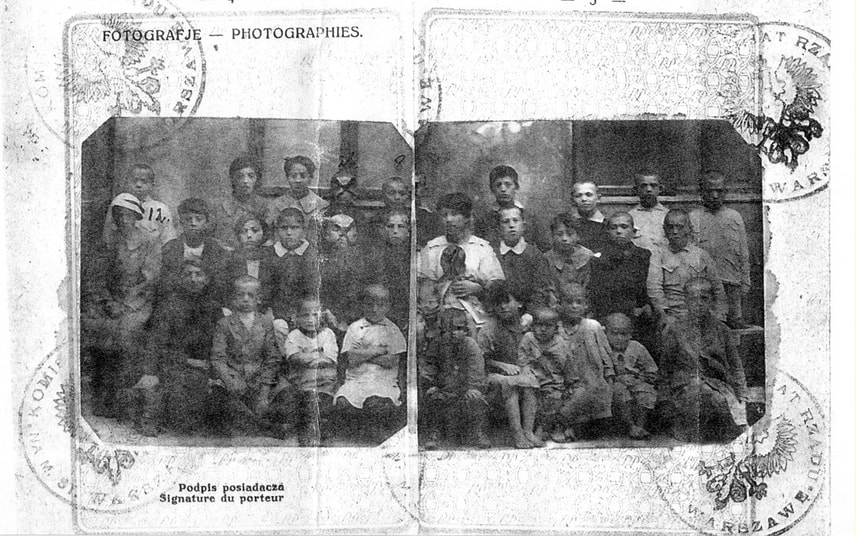

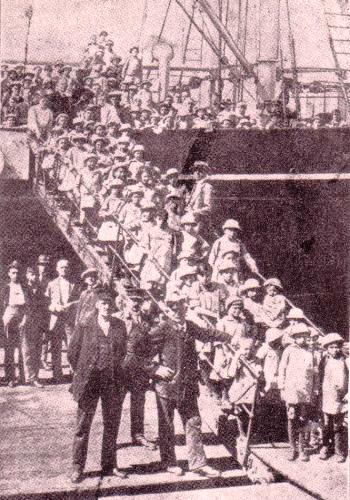

A tremendous reception awaited the orphans when they came ashore in Cape Town. So large was the group of children that the Cape Jewish Orphanage was unable to house them all, so 78 went on to Johannesburg.

A tremendous reception awaited the orphans when they came ashore in Cape Town. So large was the group of children that the Cape Jewish Orphanage was unable to house them all, so 78 went on to Johannesburg.