Currently the 70th anniversary of The Berlin Airlift is in full swing, but did you know that as South Africans we can also hold our collective heads high, having played a key role in saving the civilians of war-torn Berlin from starvation and death after the Communist ‘Iron-Curtain’ descended?

For those unaware of what The Berlin Air Lift was, and why it was so important as the saviour of West Berlin’s civilians from certain starvation and death, and even how South Africa played a role of in averting this humanitarian crisis, here’s a quick overview.

Background to the ‘Berlin Air Lift’

After the Second World War ended in 1945, Germany was divided into control zones by the victorious Allied armies so as to prevent Germany from ever re-starting another world war, however, the very act of dividing Germany did start another world war, this time “The Cold War” – and this ideological and economic war to be fought between ‘Eastern’ Communism and ‘Western’ Capitalist Democracy.

The Cold War is misunderstood to many today, as they see it as an ideological one and not a deadly one, a ‘war’ as such was never declared – and by the time the millennium came around the new generation could not understand why such a big deal was made of it.

However truth be told – The Cold War was very deadly and was to be fought in proxy wars all over the planet, and it resulted in the greatest stand-off of mutually assured nuclear annihilation ever seen – with zero dialogue or even a simple telephone line between the main belligerents – Russia (and it’s bloc Allies) one the one side and the United States of America (and its bloc Allies) on the other. The epicentre of the ‘Cold War’ began with the act of the Berlin blockade in 1948 and subsequent Airlift, and the very first casualties of the Cold War in terms of sacrifice of members of statute forces – also began with the Berlin Airlift.

So what’s with the divide?

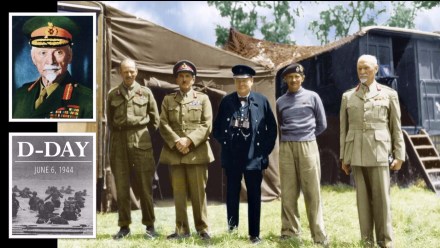

Simple put, at the conference on the 5th February 1945 towards the end of World War 2 between the ‘Big Three’ (The US, UK and Russia) at Yalta, Stalin made it clear to America and Britain that Russia was never to exposed to an attack from ‘the west’ again, they had endured the French when Napoleon invaded Russia and then endured the Germans when Hitler invaded Russia, with a massive bloodletting. In fact Russian bloodletting and sacrifice in World War 2 exceeds the British & Commonwealth, the French and American bloodletting all combined. Simply put, Stalin wanted a ‘buffer’ between Russia and Europe and everything East of Germany would become a satellite communist state to provide exactly that – with Moscow calling the shots.

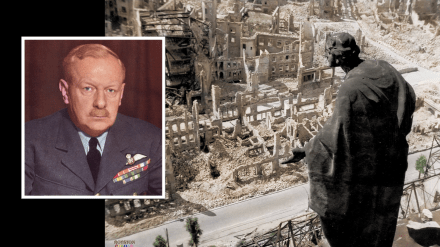

The Big Three’: Winston Churchill, Franklin D Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin sit for photographs during the Yalta Conference in February 1945.

With that the independent Parliaments, Kingdoms and Democracies of ‘liberated’ small states like Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), Bulgaria, Hungary, Croatia and Poland all but disappeared into a block of ‘puppet’ Communist satellite states.

In dividing up Germany to manage it post war, the ‘Western’ coalition of British, French and American Zones effectively made up what was to become ‘West Germany’ and the ‘Eastern’ Russian coalition zone (the Soviet Union) made up what was to eventually become ‘East Germany’. The capital of Germany – Berlin, was strategically important to Germany itself and although it was located well inside the ‘Soviet’ bloc it also needed to be divided into ‘West’ and ‘East’ in a similar way.

So Berlin itself had a Western sector which was divided into control zones by the Western allies – The United Kingdom, France and the United States of America, and an Eastern sector which was controlled by the Russian coalition the USSR – The Soviet Union. As Berlin was 100 miles into ‘Communist’ territory it was fed by a secured road and rail corridor which stretched from West Germany well into East Germany.

Berlin’s zones as defined after the end of WW2

Berlin, with its ‘western sectors’ was a ‘blot’ in the middle of Stalin’s ‘buffer’, it undermined his complete communist barrier splitting Europe in half (a barrier Churchill tagged very aptly as ‘The Iron Curtain’). Berlin was an island of Capitalism in the middle of a sea of Communism, a beacon of Western democracy contrasting to the ideals of socialist conformity – it simply had to go.

The ‘Trigger’

In June 1948, Britain, France and America united their zones into a new country, West Germany. On 23 June 1948, they introduced a new currency – the Deutschmark, which they said would help trade and aid West Germany’s war debt repayments by pulling it out of recession and the ‘cigarette economy’ it was in.

The Soviets, however, hoping to continue the German recession, refused to accept the new currency, in favor of the over-circulated Soviet Reichsmark. By doing so, the Soviets believed they could foster a communist uprising in postwar Germany through civil unrest. By March 1948 it was evident that no agreements could be reached on a unified currency or quadripartite control of Germany. Both sides waited for the other to make a move.

The Soviets, trying to push the west out of Berlin, countered this move by requiring that all Western convoys bound for Berlin travelling through Soviet Germany be searched. The “Trizone” government (Britain, France and the USA), recognising the threat, refused the right of the Soviets to search their cargo. The Soviets then cut all surface traffic to West Berlin on June 27. American ambassador to Britain, John Winnant, stated the accepted Western view when he said that he believed “that the right to be in Berlin carried with it the right of access.” The Soviets, however, did not agree. Shipments by rail and the autobahn came to a halt. A desperate Berlin, faced with starvation and in need of vital supplies, looked to the West for help.

The Soviet Union’s unprecedented move to prevent the introduction of the new currency and cut off East Germany from West Germany by way of a blockade – was the ‘trigger’ and less so the ’cause’, the much-anticipated Soviet Communist ‘Iron Curtain’ finally fell dividing the whole Europe.

As Berlin sat in East Germany, the blockade isolated the western half of the city from supply of vital coal and fuel (for heating and transport) and food. The Western Allies saw this blockade as an aggressive and ‘illegal’ Soviet move to absorb West Berlin into the Soviet Union, and the precursor to starting a 3rd World War with the Western Allies (the Cold War had begun in effect).

The Plan

The restrictions prevented the supply of food and materials by road from the British, American and French occupation zones in West Germany to their zones in West Berlin. So the Western Allies overcame the problem by creating an air bridge instead and came up with a very ambitious plan to ferry in supplies using transport aircraft – the air-space over East Germany to Berlin was not contested, and the Allies gambled that the Soviet Union would not make the error of initiating an act of war against the West by shooting one down.

British and American air force officers consult an operations plan giving routes and heights of all aircraft in and out of the Berlin area during the Airlift.

An airlift on this scale had never been attempted before (and has never been achieved again). It required military transport aircraft to fly into Berlin round the clock for weeks on end, until the Soviet resolve was broken. It was also critical, the city of Berlin had been destroyed during the Second World War, many of its citizens living hand to mouth.

Logistics

Nothing short of a logistics miracle to heat and feed West Berlin by air and during the around-the-clock airlift (in the end some 277,000 flights were made), many at 3 minute intervals, flying in an average of 5,000 tons of food and fuel each day.

Air corridor map to Berlin from the Western Allied controlled part of Germany to the Berlin in the Soviet controlled part of Germany.

The American military government, based on a minimum daily ration of 1,990 kilocalories (July 1948), a total of daily supplies needed at 646 tons of flour and wheat, 125 tons of cereal, 64 tons of fat, 109 tons of meat and fish, 180 tons of dehydrated potatoes, 180 tons of sugar, 11 tons of coffee, 19 tons of powdered milk, 5 tons of whole milk for children, 3 tons of fresh yeast for baking, 144 tons of dehydrated vegetables, 38 tons of salt and 10 tons of cheese. In all, 1,534 tons were required each day to sustain the over two million people of Berlin. Additionally, for heat and power, 3,475 tons of coal, diesel and petrol were also required daily.

To complete the task the Western Allied Command turned to the Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and South African Air Force (SAAF) for the ‘British’ contribution, the French Air Force (FAR) for the ‘French’ contribution and the United States Air Force (USAF) for the American contribution.

This would be the greatest humanitarian mission ever implemented, and South African pilots, navigators and other air-crew were right at the centre of it.

The Airlift

Operations began on 24 June 1948. The order to begin supplying West Berlin by air was approved by U.S. General Lucius Clay on June 27 with USAF AC-47s lifting off for Berlin hauling 80 tons of cargo, including milk, flour, and medicine. When the blockade first started, the city of Berlin had around 36 days worth of food.

The first British aircraft flew on 28 June 1948. At that time, the airlift was expected to last three weeks. Nothing would be further from the truth, the Airlift was to progress through a very cold winter to come.

Short Sunderland GR Mark 5 of No 201 Squadron, Royal Air Force, moored on Lake Havel in Berlin, Germany. Lake Havel was used by Coastal Command Sunderlands from July until mid-December 1948, when the threat of winter ice suspended further use.

President Truman, wishing to avoid war or a humiliating retreat, continually supported the air campaign. Surviving the normally harsh German winter, the airlift carried over two million tons of supplies in 277,000 flights, and would continue well into the new year, only to finally officially end in September 1949.

To keep the aircraft coming in at the rate of supply needed, fast turnaround was expected on the ground in Berlin. Pilots and crews generally did not leave their aircraft and were provided with snacks and meals. The German civilian population got into ensuring the airlift was a success and to make up for shortages in manpower. Crews unloading and making airfield repairs at the Berlin airports were made up of almost entirely by local civilians, who were given additional rations in return for their assistance.

USAF Dakota transport with a cargo of flour during the Berlin Airlift

As the crews experience increased, the times for unloading continued to fall, with a record set for the unloading of an entire 10-ton shipment of coal from a C-54 in ten minutes, later beaten when a twelve-man crew unloaded the same quantity in five minutes and 45 seconds.

The Candy Bombers

At the very beginning of the air-lift Gail Halvorsen, and American pilot arrived at Tempelhof on 17 July 1948 on one of the C-54s and walked over to a crowd of children who had gathered at the end of the runway to watch the aircraft and handed out his only two sticks of Wrigley’s Doublemint Gum to the children.

The children quickly divided up the pieces as best they could, even passing around the wrapper for others to smell. He was so impressed by their gratitude and that they didn’t fight over them, that he promised the next time he returned he would drop off more. Before he left them, a child asked him how they would know it was him flying over. He replied, “I’ll wiggle my wings.”

The next day on his approach to Berlin, he rocked the aircraft and dropped some chocolate bars attached to a handkerchief parachute to the children waiting below. Every day after that, the number of children increased and he made several more drops. Soon, there was a stack of mail in Base Ops addressed to “Uncle Wiggly Wings”, “The Chocolate Uncle” and “The Chocolate Flier”.

The Allied Command was so impressed by this gesture of goodwill and its ‘public relations’ value that the mission was expanded into “Operation Little Vittles”. Up to this point the children of Berlin only knew that American and British aircraft brought bombs, fire, death and destruction. Now, in a pure expression of humanity the aircraft would bring happiness to children in what was to them a break and traumatized time, the Western Allies would now drop candy instead of bombs.

Children of Berlin wave to a ‘Candy Bomber’ to get the attention of the air crew.

The other air-lift pilots joined in, and when news reached the United States, children all over the country sent in their own candy to help out. Soon, major candy manufacturers joined in. In the end, over twenty-three tons of candy were dropped on Berlin the “operation” became a major propaganda success. German children christened the candy-dropping aircraft “raisin bombers”.

On December 20, 1948 “Operation Santa Claus” was also flown from Fassberg, with gifts for 10,000 children.

Sacrifice

The airlift was not without its hazards, with that many aircraft on that type of complex operation flying in all sorts of conditions – instrument and visual, and weather, so there we bound to be accidents.

There were 101 fatalities recorded during the Airlift. The number includes 40 British and Commonwealth air-crew and 31 American air-crew. The majority died as a result of accidents resulting from hazardous weather conditions or mechanical failures. The remainder is composed of civilians who perished on the ground while providing support for the operation or who lost their lives when aircraft accidents destroyed their homes. As aircraft losses go 17 American and 8 British aircraft crashed during the Berlin Airlift.

In honor of the pilots and aircrews who were lost the Berlin Airlift Monument was created from a fund established by the former Federal Republic of Germany and private donations. It was dedicated in 1951. All together there are three matching monuments: at Rhein-Main Air Base near Frankfurt, at Wietzenbruch near the former British airbase Celle, and at the Luftbruckenplatz (Airbridge Place) Berlin-Tempelhof airfield. The base of the monument at Tempelhof reads, “They gave their lives for the freedom of Berlin in service for the Berlin Airlift 1984/1949.” The location at Tempelhof is presently being considered as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

South African service personnel in the airlift

The full list of South African pilots and aircrew is hard to come by as the commitment of South Africans in the Berlin Airlift is not generally part of the South African national consciousness anymore – whereas in countries like the United States of America, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada it is.

On the 27th September 1948, Union government of South Africa committed 50 South African Air Force (SAAF) crew to the Berlin Airlift, in all the SAAF would provide two contingents of air-crew to the air-lift, most seconded to RAF Transport Command and even one SAAF registered C-47A Dakota transport aircraft (No. 6841) made its way to Berlin to be put into service.

South Africans known to us at the moment who took part in the Berlin Airlift include Steve Stevens, who participated in WW2 as a SAAF Beaufighter pilot, Albie Gotze who participated in WW2 as a seconded SAAF pilot in RAF Typhoons and Spitfires. Joe Hurst, John Clifford Bolitho, Duncan Ralston, Jenks Jenkins, Pat Clulow, Tom Condon, Johnnie Eloff, Mickey Lamb, “Shadow” Atkinson, Jannie Blaauw, Piet Gotze, Wilhelm Steytler, Vic de Villiers, Mike Pretorius, Nic Nicholas, Jack Davis, Dormie Barlow, Tienie van der Kaay ‘Porky’ Rich, Ian Bergh (flying Sunderlands in the RAF) are all South African and SAAF pilots and air-crew recorded as taking part.

In addition SAAF pilot Joe Joubert also took part and was even commemorated for his actions during the Berlin Airlift. Joe Joubert flew as a navigator in the Berlin Airlift and on the 9th July 1949 he and the radio operator were ordered to jettison 63 sacks of coal as the aircraft could not gain height in a severe thunderstorm. This was achieved in a remarkable six and a half minutes and he received a commendation for this remarkable act. This act was certainly helped by the fact that in his spare time Joe practiced weight lifting.

Joe Joubert (right) – a SAAF pilot in the Berlin Airlift to earn a special commendation

Flt Officer Kenneth Reeves is South Africa’s only casualty during the Berlin Airlift, and he symbolises the greatest sacrifice we as a nation can give. Kenneth was a navigator on board a RAF CD-3 (Dakota) which crashed in the Soviet Zone near Lübeck, killing all the crew.

Light at the end of the tunnel

By the spring of 1949, the airlift was clearly succeeding, and by April it was delivering more cargo than had previously been transported into the city by rail. On 12 May 1949, the Soviet Union finally realised the futility of the road and rail blockade of West Berlin and lifted it, however tensions remained.

Air crew of the Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) and South African Air Force (SAAF) enjoy an off-duty drink in the officers’ bar at RAF Lubeck. IWM Copyright.

The airlift however continued until 30th September 1949, at a total cost of $224 million and after delivery of 2,323,738 tons of food, fuel, machinery, and other supplies. The end to the blockade was brought about because of countermeasures imposed by the Allies on the Soviet blockade by way of the airlift and because of a subsequent Western embargo placed on all strategic exports from the Eastern bloc. As a result of the blockade and airlift, Berlin became a symbol of the Allies’ willingness to oppose further Soviet expansion in Europe.

In conclusion

There can be little doubt that the Airlift was a success on many levels. It saved millions of lives and preserved the freedom of the city of Berlin. Veterans’ groups world over still celebrate the victory by gathering around the bases of the monuments and laying wreathes and flowers in memorial for those who paid the ultimate cost. This act of remembrance made even more important on the 70th Anniversary.

However little recognition is given to the Berlin Airlift in South Africa, These are truly “unsung” heroes of South Africa we can be very proud of and not to be forgotten. The South Africans who took part in the Berlin Airlift are icons in Germany, and hardly known in South Africa, such is the strange politics we as South Africans tend to weave.

The Berlin Airlift marks South Africa’s first sacrifice in the ‘Cold War’ – further sacrifice was to come in the other future ‘Cold War’ proxy wars – fought by South African statute forces against Soviet Allies in Korea, Namibia, Angola and Mozambique.

To many of the South African air-crew and SAAF members who took part in this momentous period in world history, the saving of a city from near starvation, the Capital City of a former enemy now vanquished by the war, with this act of sheer human philanthropy and benevolence was to really end South Africa’s “war” on a very humane high.

We leave the Cold War where it started and in one fitting epitaph the last British pilot to leave Berlin had chalked on the side of his aircraft the words, “Positively the last flight…Psalm 21, Verse 11” That psalm reads:

“If they plan evil against you, if they devise mischief, they will not succeed.”

Related links and work

Jan Smuts Barracks Berlin Smuts Barracks; Berlin

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens.

Source The South African Air Force Museum. The Imperial War Museum. Image copyrights (see watermark) – Imperial War Museum.

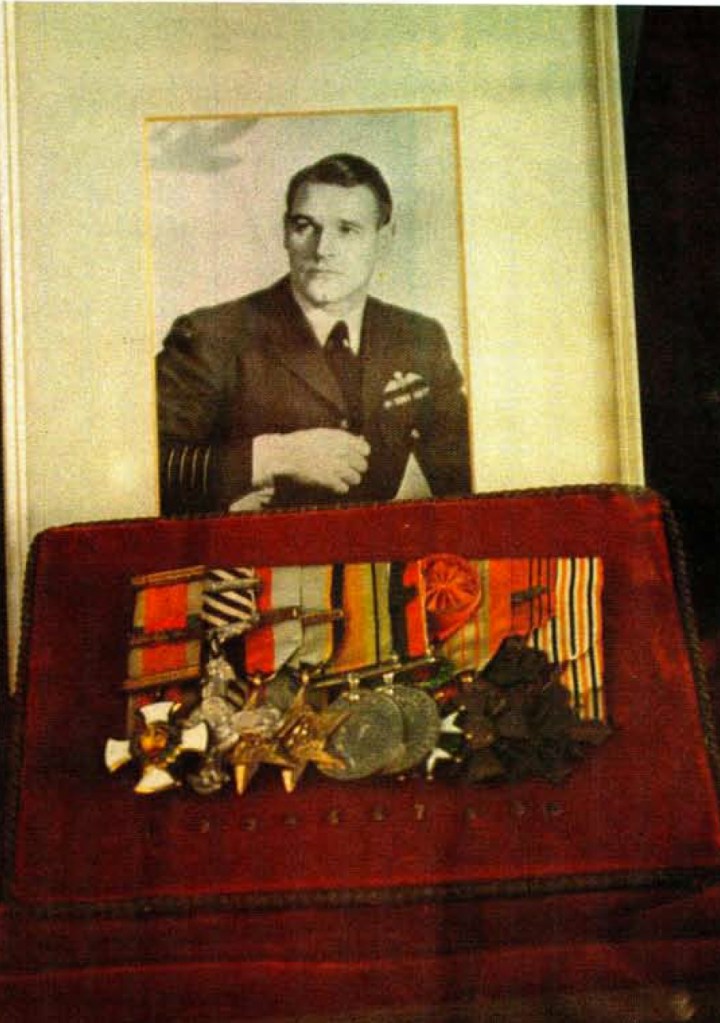

As all the eye-witness reports indicate strongly that Percy Burton deliberately rammed the Bf 110 in an act of sacrifice. In a letter from Fighter Command to the Hailsham ARP Chief, Percy Burton was recommended that for this action, bravery and sacrifice at Hailsham that he receive a posthumous Victoria Cross.

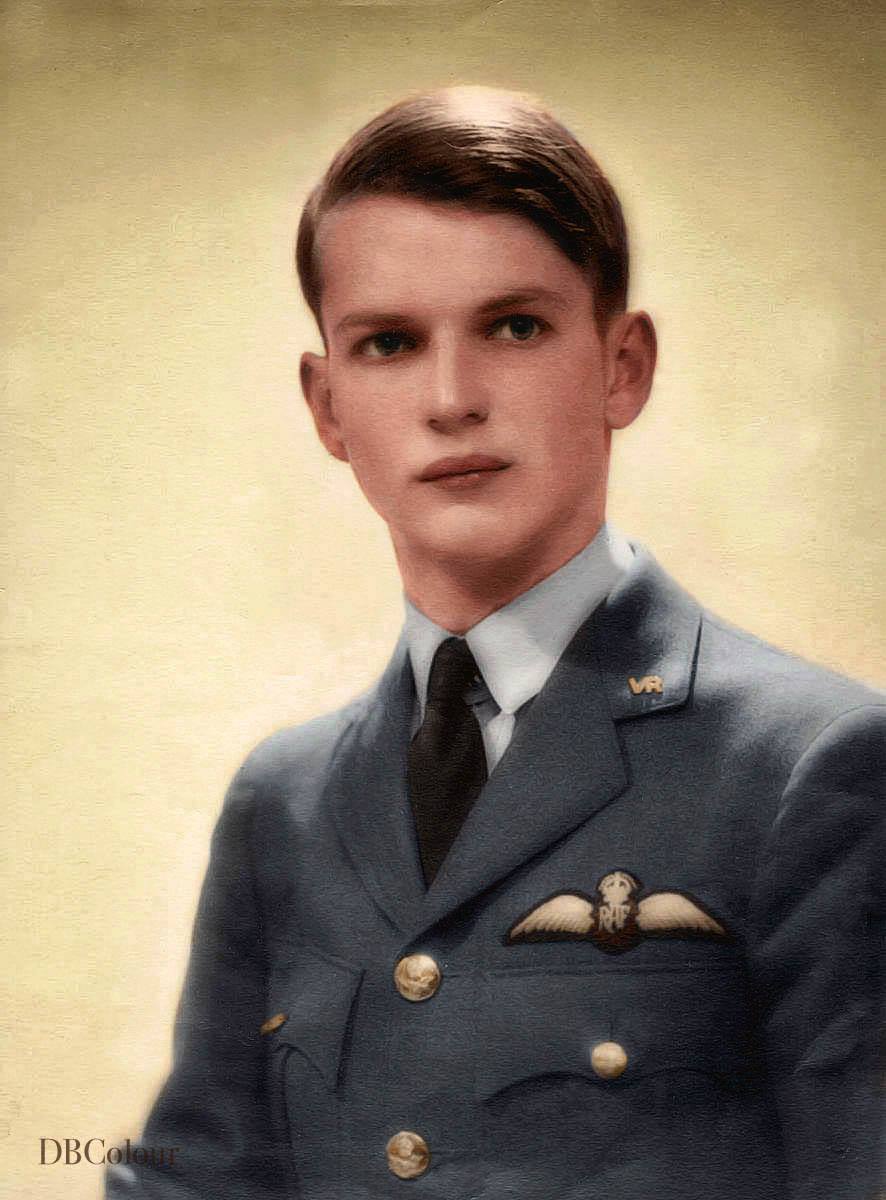

As all the eye-witness reports indicate strongly that Percy Burton deliberately rammed the Bf 110 in an act of sacrifice. In a letter from Fighter Command to the Hailsham ARP Chief, Percy Burton was recommended that for this action, bravery and sacrifice at Hailsham that he receive a posthumous Victoria Cross. Looking at this recently colourised image of Percy Burton by Doug, we are reminded of just how young these brave men were, Percy Burton was just 23 years old when he boldly sacrificed his life. In perspective he was the ‘millennial’ of his time, however it is very difficult to imagine a modern millenial facing the hardship, morality, bravery and sacrifice that this – the ‘greatest generation’ – faced.

Looking at this recently colourised image of Percy Burton by Doug, we are reminded of just how young these brave men were, Percy Burton was just 23 years old when he boldly sacrificed his life. In perspective he was the ‘millennial’ of his time, however it is very difficult to imagine a modern millenial facing the hardship, morality, bravery and sacrifice that this – the ‘greatest generation’ – faced.

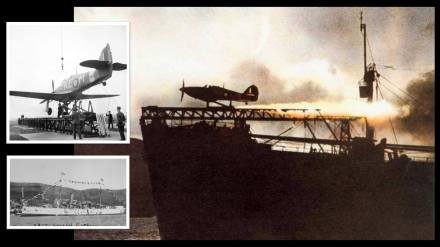

“Pilot Officer Hay was pilot of the Hurricane on board a ship fitted with a catapult. On the approach of enemy aircraft he was catapulted off and immediately proceeded to attack and drive off a formation of six Heinkel 111’s and 115’s which were preparing to deliver a torpedo attack on the port bow of the convoy; not only did this prevent synchronisation with an attack which developed from the starboard bow, but he destroyed one Heinkel 111 and slightly damaged another. Pilot Officer Hay was himself wounded and he then baled out and was picked up by one of His Majesty’s ships of the convoy escort. He showed great gallantry and his spirited attack was a great encouragement to all the convoy and escorts, and cannot but have been a great discomfort and surprise to the enemy.”

“Pilot Officer Hay was pilot of the Hurricane on board a ship fitted with a catapult. On the approach of enemy aircraft he was catapulted off and immediately proceeded to attack and drive off a formation of six Heinkel 111’s and 115’s which were preparing to deliver a torpedo attack on the port bow of the convoy; not only did this prevent synchronisation with an attack which developed from the starboard bow, but he destroyed one Heinkel 111 and slightly damaged another. Pilot Officer Hay was himself wounded and he then baled out and was picked up by one of His Majesty’s ships of the convoy escort. He showed great gallantry and his spirited attack was a great encouragement to all the convoy and escorts, and cannot but have been a great discomfort and surprise to the enemy.”

Flight-Lieutenant Alistair James Hay DFC was tragically killed on the 18 August 1944 whilst taking part in the Battle of the Falaise Gap flying RAF Typhoon, serial number JP427 and he encountered flak near Vimoutiers and was shot down.

Flight-Lieutenant Alistair James Hay DFC was tragically killed on the 18 August 1944 whilst taking part in the Battle of the Falaise Gap flying RAF Typhoon, serial number JP427 and he encountered flak near Vimoutiers and was shot down.

Formed during WW1, 222 Squadron was reformed at the onset of WW2 at Duxford on 5 October 1939 and in March 1940 the squadron re-equipped with Spitfires. It initially took part in the Dunkirk evacuation and the Battle of Britain. Later in the war it would participate in Overlord and the D-Day landings as well as Operation Market Garden.

Formed during WW1, 222 Squadron was reformed at the onset of WW2 at Duxford on 5 October 1939 and in March 1940 the squadron re-equipped with Spitfires. It initially took part in the Dunkirk evacuation and the Battle of Britain. Later in the war it would participate in Overlord and the D-Day landings as well as Operation Market Garden.

A number of South African Air Force fighter pilots served during Operation Overlord flying RAF Typhoons and Spitfires and because of the highly treacherous nature of the operations a handful of about five South African Air Force pilots lost their lives.

A number of South African Air Force fighter pilots served during Operation Overlord flying RAF Typhoons and Spitfires and because of the highly treacherous nature of the operations a handful of about five South African Air Force pilots lost their lives.