Torch Commando Series – Part 5

The Smoking Gun

The military ‘struggle’ of White South Africans against Apartheid is a complex one seldom acknowledged. It’s politically ‘inconvenient’ history and hidden from the mainstream. It is often presented in a fragmented manner, somehow dipping in and out of the struggle narrative as a ‘few’ whites with a conscience prepared to forsake their Apartheid white privilege. The advent of this narrative now deepened by revolutionist rhetoric which by its very nature is very unbalanced.

The simple truth is that the ‘white’ struggle against Apartheid is far from a mere side note in the annals of South Africa’s liberation struggle. A full understanding the ‘white’ struggle exposes one overarching truth, the history of the struggle against Apartheid has less to do with race and more to do with ideology. Race was the raison d’être for Apartheid as an ideology, so it’s hard for many to step away from the logic that says race must therefore be the raison d’être for the liberation ‘struggle’ – but step away we must, the ‘struggle’ was an ideological one.

This misdirected populist perspective of a struggle between ‘black’ and ‘white’, makes it necessary to pack out the ‘white’ struggle along a racial line to show the flaw in the current narrative. So, to fully understand the ‘white’ struggle against Apartheid, we need to first find and follow its ‘Golden thread’ – the key task of historians to find the ‘smoking gun’ and tell the story in a sequential way. With a little historical sleuthing we need to see the ‘golden thread’ – and connect the dots in order for the history of the ‘struggle’ to be holistically understood.

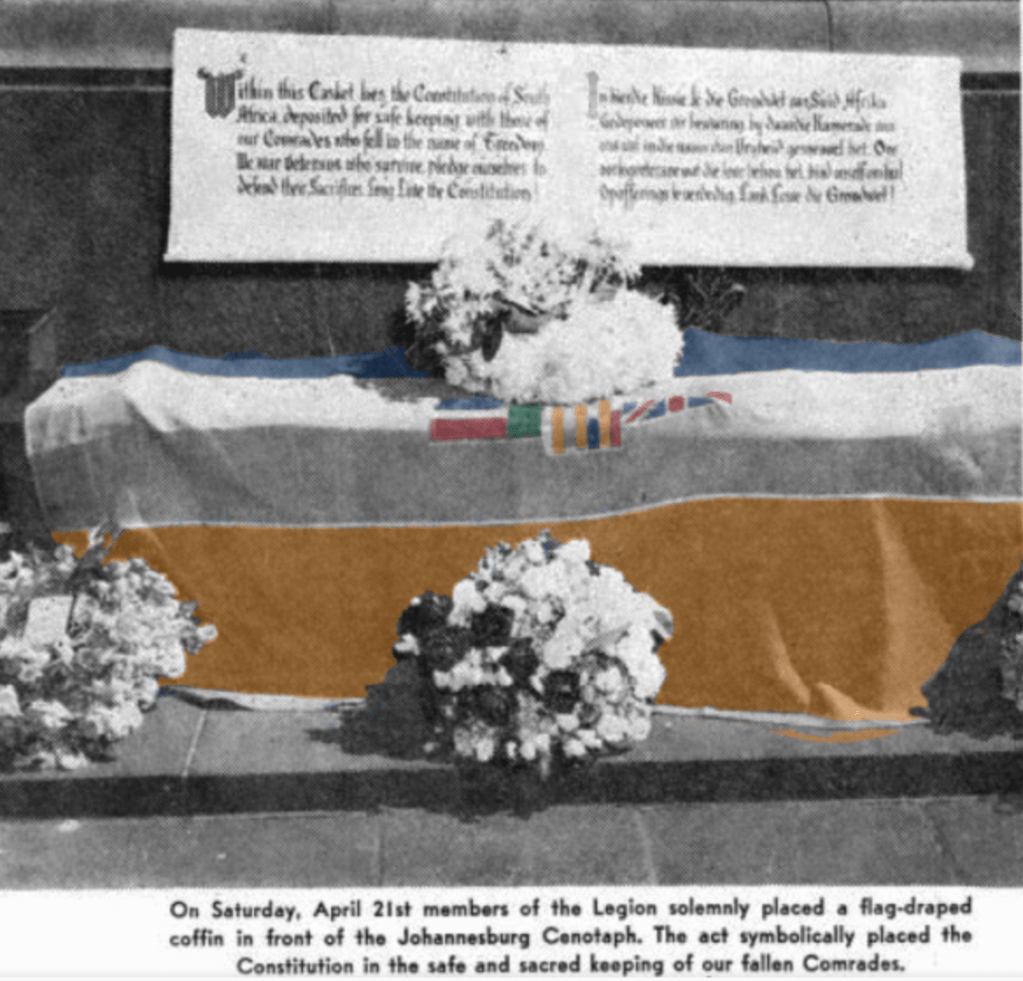

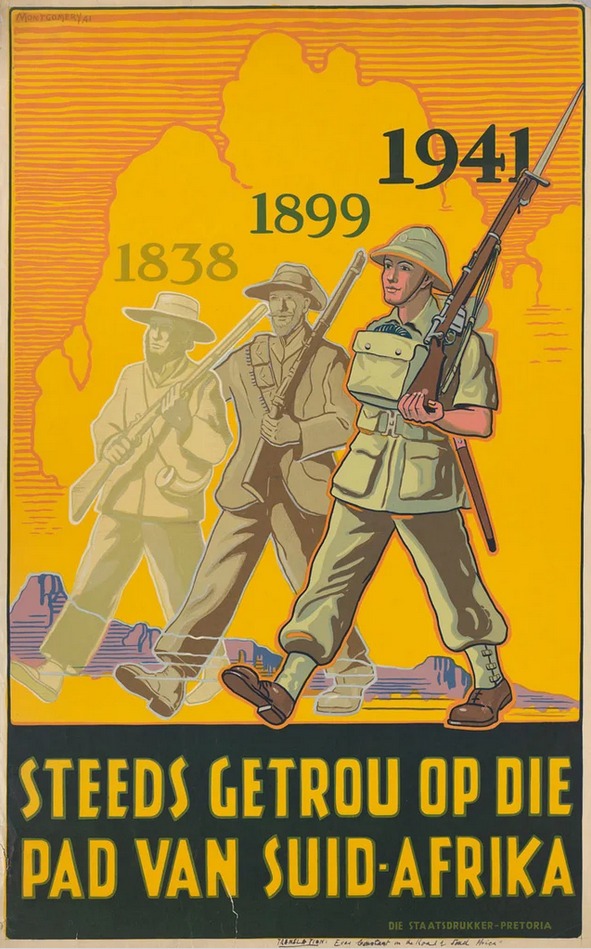

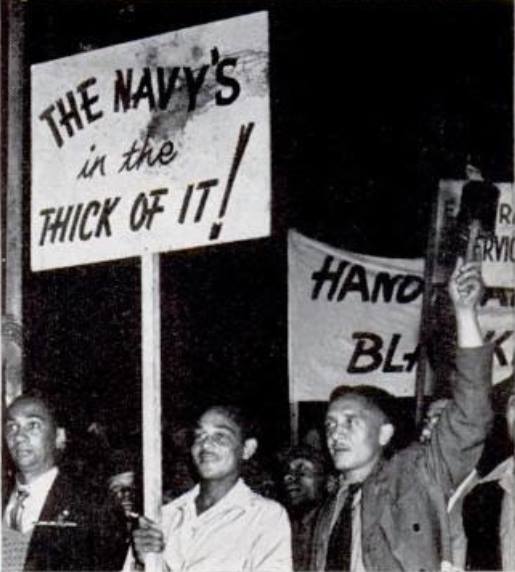

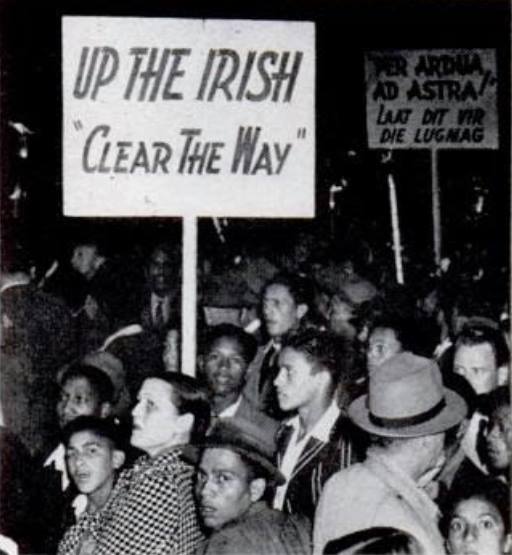

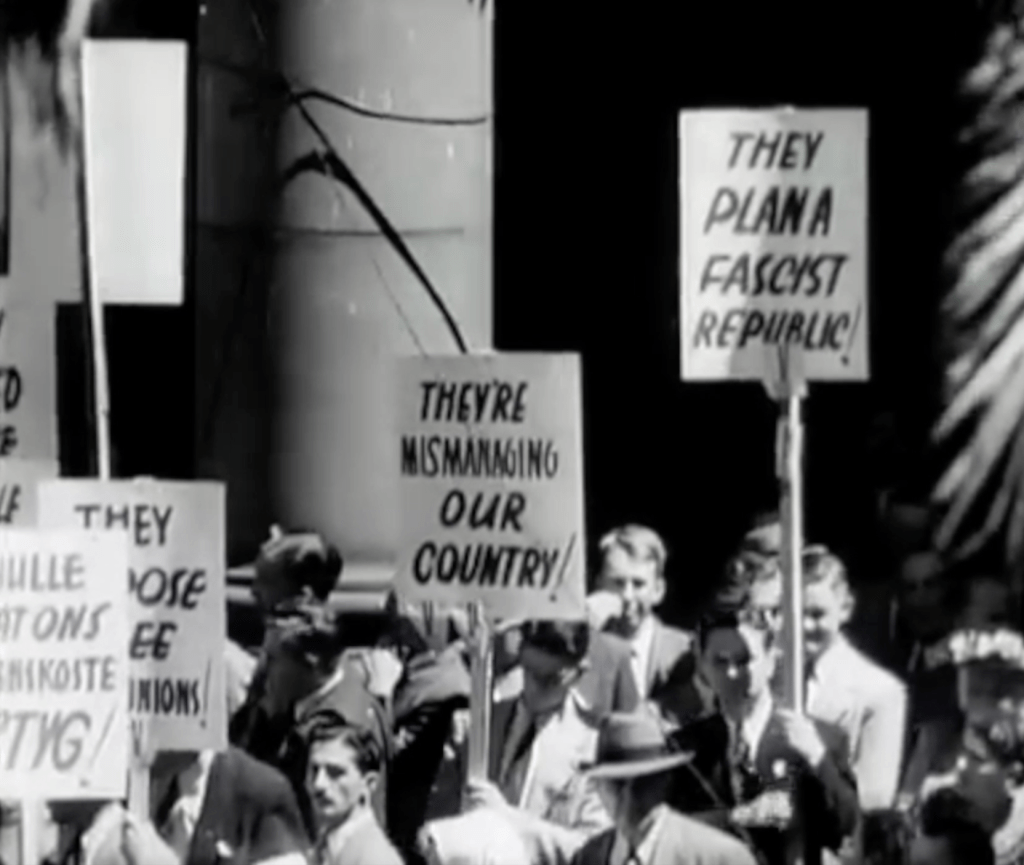

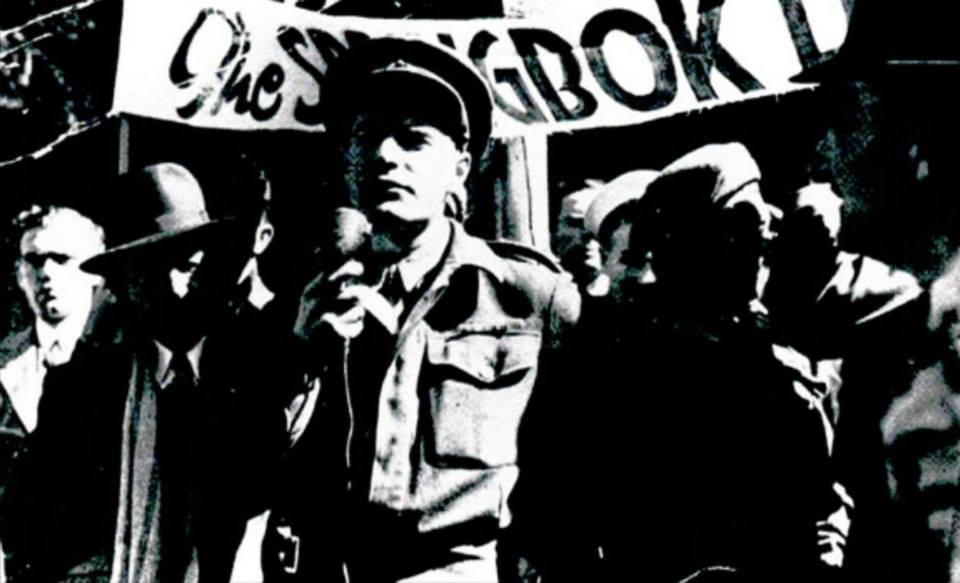

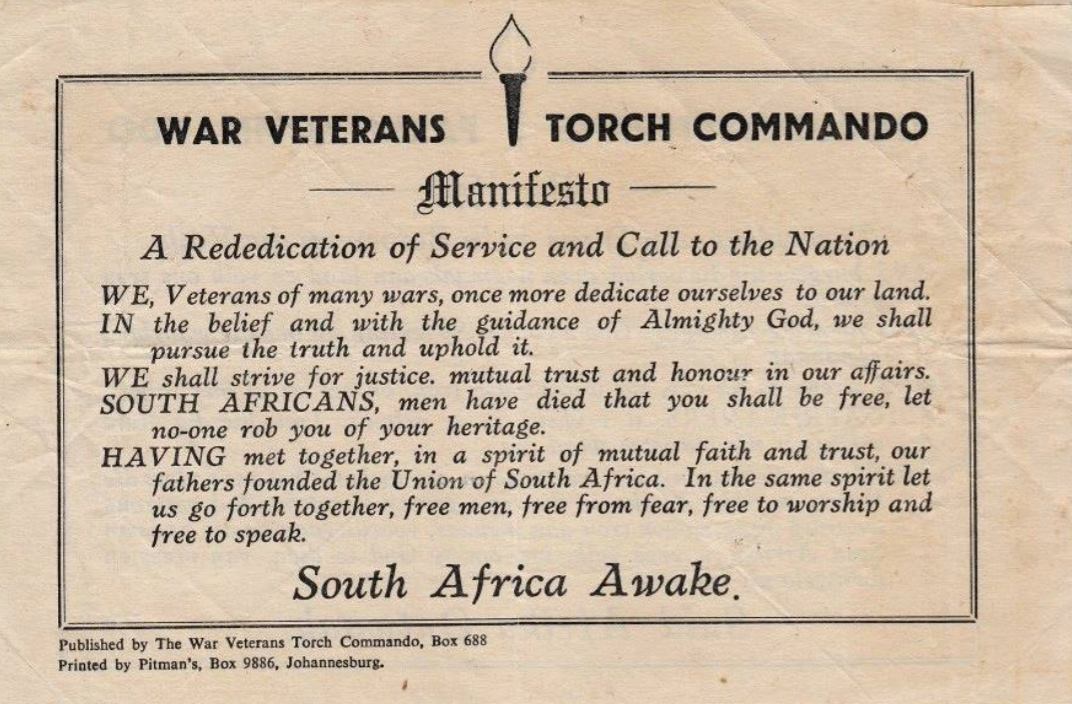

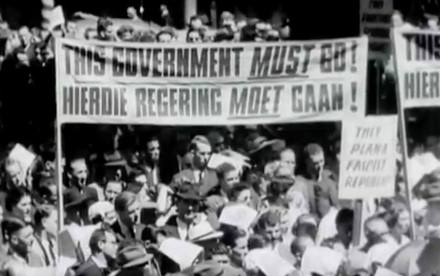

The ‘smoking gun’ for the ‘white struggle against Apartheid’ begins in earnest with a military theme and a post-World War 2 military veteran’s formation. The Torch Commando, a mass movement of mainly white ex-servicemen and supporters who mobilised against Apartheid; 250,000 in total. Not a common feature on South African history of the ‘Struggle’ – simply put it does not suit the current political rhetoric and broad popular understanding of the ‘struggle’ – so how did this come about?

In a nutshell, The Torch Commando mission came on the back of a ‘Constitutional’ (not majority win) of the National Party in 1948 to push for another more representative election and The Constitutional Crisis’ that follows the Afrikaner Nationalist government’s first attempts at Apartheid legislation. The Torch views its fight as an extended anti-fascism one against ‘the rise of the Afrikaner Reich’ and sees a quarter of the 1948 ‘White’ voting base (of an est. 1,000,000), known as the ‘service vote’ – actively mark their protest against the National Party’s accent to power in a mass ‘pro-democracy’ and ‘anti-Apartheid’ movement.

The Torch’s activation pre-dates the African National Congress’(ANC) activation of their ‘Defiance Campaign’ (which activated on 26 June 1952) and as such ‘The Torch’ as it became to known is the first significant mass protest movement against the intuition of Apartheid legislation, and at the time it posed more significant threat to the National Party than the ANC – militarily, numerically and politically speaking.

The ‘numeric’ threat alone made the National Party uneasy as it highlighted just how tenuous their new grip on South Africa was, statistically the majority of whites wanted nothing to do with their election promise of ‘Apartheid’ and had voted against them in 1948 (they won by ‘seats’ and not by a majority) and now literally half of the white people who voted against them had gone one step further and joined a mass movement in active protest, a mass movement led by a group of men who were militarily commanders and well experienced in waging war and comprising tens of thousands of very experienced war veterans.

Heady and dangerous stuff for the fledgling Architects of Apartheid – so let’s have a look at this movement a little closer and figure out what happened and why the ‘Torch’ is the epicentre of the ‘white’ militant struggle against Apartheid.

What happens next?

What arises from the ashes of The Torch’s mass political uprising against the Nationalists and Apartheid post the April 1953 General Election National Party victory? The answer lies in the Torch’s broach church and mixed bag of ex-military servicemen and women. These leading members of The Torch Commando, with their differing ideologies, will move on to re-shape the political landscape and resistance to Apartheid in the coming years.

Broadly the leader element of The Torch Commando comprises groupings of individual members who follow entirely separate ideologies – one faction can be described as ‘Liberals’ the second faction are ‘Communists’, the third faction can be described as ‘Democrats’ and finally there are Torchmen who are ‘Federalists’. Let’s examine each separately.

At the same time the Torch folds in mid 1953, the ‘Liberal’ Torch members become the founders of The Liberal Party – formed in May 1953. Louis Kane-Berman (The Torch’s Chairman) would recall that the Liberal Party which literally take shape at his house, although Louis Kane-Berman himself became a federalist, favouring the Union Federal Party. Central to the Liberal Party’s formation is the failing of the UP to adequately address the black franchise question.

The ‘communist’ members of the Torch, limited by the Suppression of Communism Act 1950 and using the Torch Commando for political voice as The Springbok Legion would maintain their Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) identity and fall into lock step with the African National Congress. In late 1951, the Torch Commando moves onto a ‘anti-Communist’ footing and into lock step with the United Party so as to maintain its broad appeal amongst white voters as an anti-fascist protest movement. The Torch had “donned the straightjacket of anti-Communist orthodoxy” according to the very liberal leaning Guardian newspaper on 6 September 1951.

The Torch’s key Springbok Legion and ‘Communist’ leaders are eventually swept up or fingered in 1956 when the Treason Trial begins, the trial forces most of them underground. After the Sharpsville massacre in 1961 all of them find themselves in jail or in exile.

The ‘democratic’ members of the Torch, who are also disillusioned members of the UP, especially on the UP’s appeasement politics on race relations, would break away from the UP and play key roles in forming the Progressive Party in 1956. This would be the pre-curser to what is now the Democratic Alliance (DA) today. In many respects it is the Torch Commando’s fire-brand politicians demanding the United Party radically change its position on Black political empowerment and open up the franchise who would ultimately end the United Party.

The ‘Federalists’ in the Torch would also split out of the United Party and peruse an agenda for a qualified franchise and push another constitutional crisis over the Natal breakaway proposal. After the Torch collapses many of these ‘UP’ torchmen would form the Union Federal Party (UFP).

Depending on their moral convictions, out of these respective breakaways and political parties and movements would emerge a two stream ‘white’ resistance campaign to Apartheid. One stream which focused its military experience on armed resistance and one stream, traumatised and tired of armed conflict, choose civil resistance instead. Both streams would continue with a struggle or a continued fight against ‘Nazim’ and the on-set of the ideology in South Africa under the guise of Afrikaner Christian Nationalism.

So, who are these leaders who are embroiled in the Torch Commando and why are they so important to South Africa’s future democracy? First, let’s start with the Communists.

The Torch’s Communists

The communist element of the Springbok Legion and subsequently the Torch Commando are made up of the following key persons:

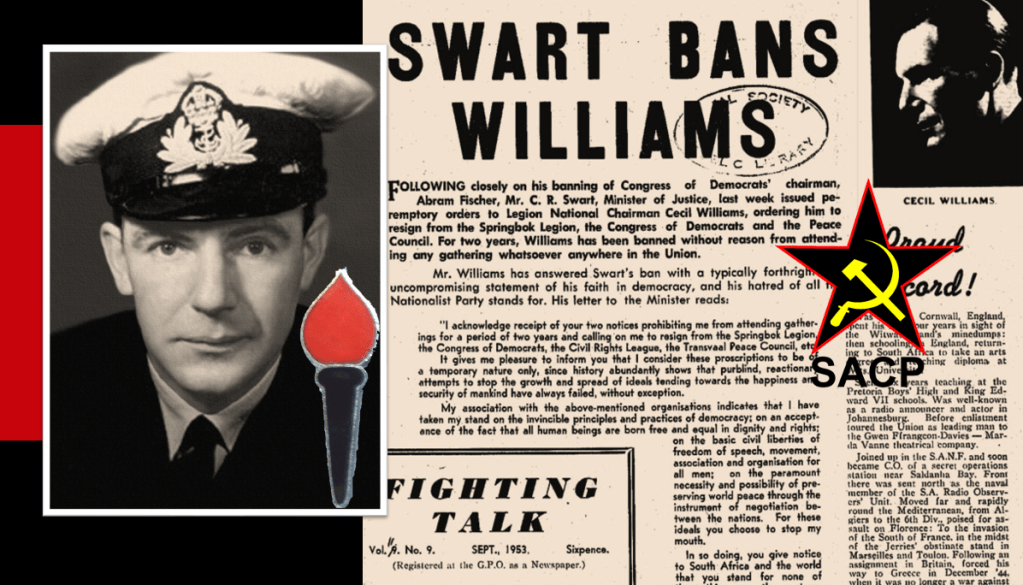

Cecil Williams

Cecil Willams’ wartime experience was with the Royal Navy (RN) as a RN War Correspondent in the Mediterranean theatre. He joins The Springbok Legion as its Secretary and later becomes its Chairman. A paid-up Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) member, he becomes the administrative officer of the Torch Commando’s “Steel Commando”.

Cecil Williams sought a broad-based white front against the Nationalists and called on the Torch Commando to declare a national strike. He foresaw that the Nationalists would not be ousted in the 1953 General Election, a new delimitation would favour the Nationalists; opponents could be banned or proscribed, and hooligans could stop people voting. He called for a National Strike to make it impossible for the government to continue governing stating it “would unite all anti-Nationalist sections of the population; would prove the government did not reflect the will of the majority; and would show people that power lay in their hands” (Clarion, 17 July 1952).

Cecil Williams later joins the African National Congress (ANC) and is famously arrested on the 5th August 1962 whilst being ‘chauffeured’ by Nelson Mandela. Driving an Austin Westminster, Mandela was able to travel around the country secretly to meetings post the Sharpeville massacre by disguising himself as a chauffeur for an elegant, impeccably dressed white man (Cecil Williams). Nelson Mandela would famously recall of the day “I knew in that instant my life on the run was over”.

Williams is detained, banned and ultimately goes into exile in the United Kingdom (UK). He pioneers gay rights in the UK in addition to anti-Apartheid activism and he died in London in 1979. A movie about his life “The Man who Drove with Mandela” was released in 1998, and given his influence over Mandela and other ANC stalwarts at this time in history, many would later conclude Cecil Williams had planted the seeds that saw South Africa become the first country in the world to embody equal LGBT rights in its post-apartheid constitution.

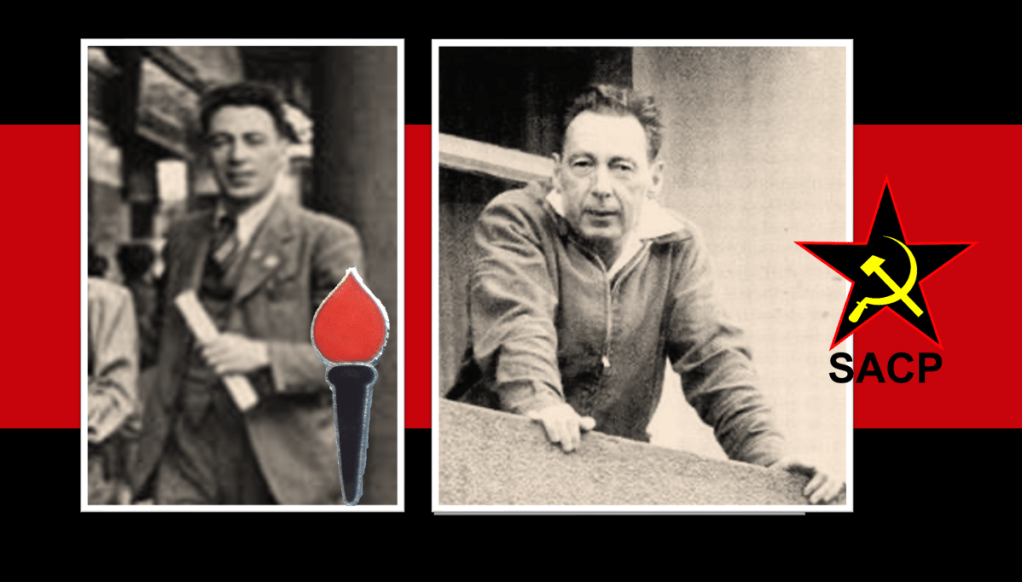

Wolfie Kodesh

Wolfie Kodesh sees his military experience in the South African Army fighting in East and then North Africa during World War 2. Also, a card-carrying member of the Communist Party, The Springbok Legion and The Torch Commando. After the collapse of the Torch Commando and banning of Communism, he puts his logistics and military planning skills to use, secretly moving Nelson Mandela around to avoid arrest. Acting as an uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) Counter-Intelligence and logistics officer he also trains ANC cadres on weapons and co-ordinates communications.

Wolfie Kodesh is also credited with introducing Nelson Mandela to Communist military doctrine and tactics and becomes a founding member of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK). Wolfie Kodesh was a director of The New Age Newspaper, vocally in opposition to Apartheid. In 1963 he was arrested and detained without trial in solitary confinement for 90 days, thereafter he was deported to the United Kingdom (UK). While he was abroad, he worked for the ANC until he was deployed to work in MK camps. He later took charge of logistics for MK in Lusaka, Zambia. He returned to South Africa after the end of Apartheid and died in Cape Town in 2002.

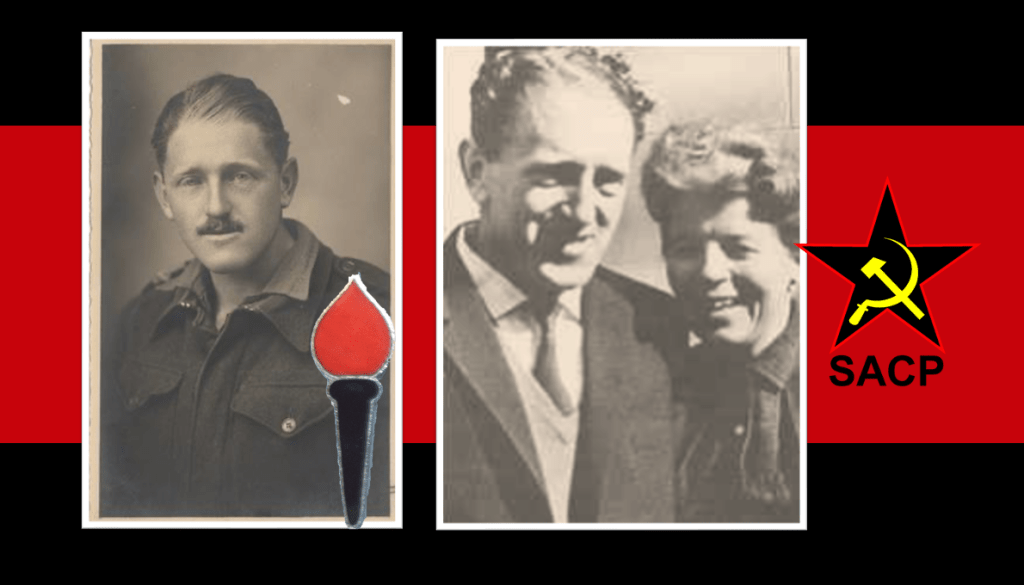

Percy John ‘Jack’ Hodgson

Jack Hodgson’s service during the second world war is in the South African Army where he is deployed in the Western Desert. He is severally wounded under fire and after a long spell in military hospital, he was invalided out in 1943. He marries Rica Hodgson after the war in 1945. Rica and Jack both become a highly active anti-Apartheid team.

A very experienced combat soldier and hard-line Communist Party member, he becomes the National Secretary of the Springbok Legion leading the Legion’s campaign against the National Party in the 1948 election. In opposition to the National Party’s 1948 win he then plays a key role in setting up The Torch Commando and continued in a highly active role in the Torch’s activities and protests. When the Torch Commando collapsed in 1953, he went on to become a founding member of the Congress of Democrats aligning with The African National Congress (ANC).

Under the Suppression of Communism Act, he is served banning orders in November 1953 and goes underground. He is arrested, charged and acquitted in the Treason Trial in 1956, and along with fellow Springbok Legion and Torch Commando stalwart Wolfie Kodesh at his side, he becomes part of Mandela’s security detail during the trial. Rica Hodgson also takes an active role as the secretary of the Treason Trial Defence Fund.

After the trial Jack Hodgson gets involved in the formation of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and becomes part of MK’s Johannesburg High Command. He is the person who introduces Nelson Mandela to art of bomb-making and “brings the bomb” to the ANC’s first test bombing at a brickyard outside Johannesburg. He involves himself in all aspects military for MK and spends much of his time training MK cadres in bombmaking.

He is detained and eventually deported to the UK along with Rica. In the UK Jack sets up a workshop producing false passports, letter bombs and fake suitcase bottoms to smuggle covert material into South Africa on behalf of MK. Jack Hogson died in London in 1977, Rica Hodgson returned to South Africa as Walter Sisulu’s secretary after the Communist Party and ANC was unbanned in 1991 and she passed away in 2018.

Lionel ‘Rusty’ Bernstein

Rusty Bernstein at the onset of WW2 he joins the South African Army, serving as an artillery man in all major theatres of South African operations during the war; East and North Africa and finally in Italy. Another highly politicised member of the Communist Party, Springbok Legion and then The Torch Commando – he is eventually charged during the Treason Trial and acquitted, only to be charged again and detained for the Rivonia Trial. He is the only man to be acquitted during the Rivonia Trial.

Rusty Bernstein is accredited as the person who crafts the Freedom Charter, he was detained without charge for almost five months during the post Sharpeville state of emergency, thereafter banned he goes into exile. In exile he joins uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and plays a key role in educating MK cadres and others in African struggle politics whilst in the Soviet Union at the Lenin School in Moscow and at the Solomon Mahlangu College in Tanzania.

In 1994 he returned to South Africa for Nelson Mandela inauguration as President and then returned to Britain until his death in 1999.

Joe Slovo

Joe Slovo, politicised early Joe joins the Communist Party at the onset of World War 2, to get in on the fight on the side of the Allies, he joins the South African Army as a signaller and serves in both the North African and Italy campaigns. He plays a pivot role in the Springbok Legion and the Torch Commando. Like his other Communist comrades in The Torch and Springbok Legion he finds himself gagged by suppression of communism act and voiceless when the Torch and Springbok Legion collapse. He is associated with the Treason Trial and acquitted and like Rusty Bernstein takes a role in contributing to The Freedom Charter.

Joe Slovo becomes a Founding member of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and forms part of its High Command later establishing an operational centre for MK in Mozambique and becoming MK’s Chief of Staff. During this period, he would be the military strategist and chiefly accountable for nearly all MK’s military operations in South Africa. Like the Hodgson’s, he formed a strong anti-apartheid coalition with his wife, Ruth First who was also a committed Communist. Ruth was killed in 1982 in Mozambique when the South African security police sent her a letter bomb.

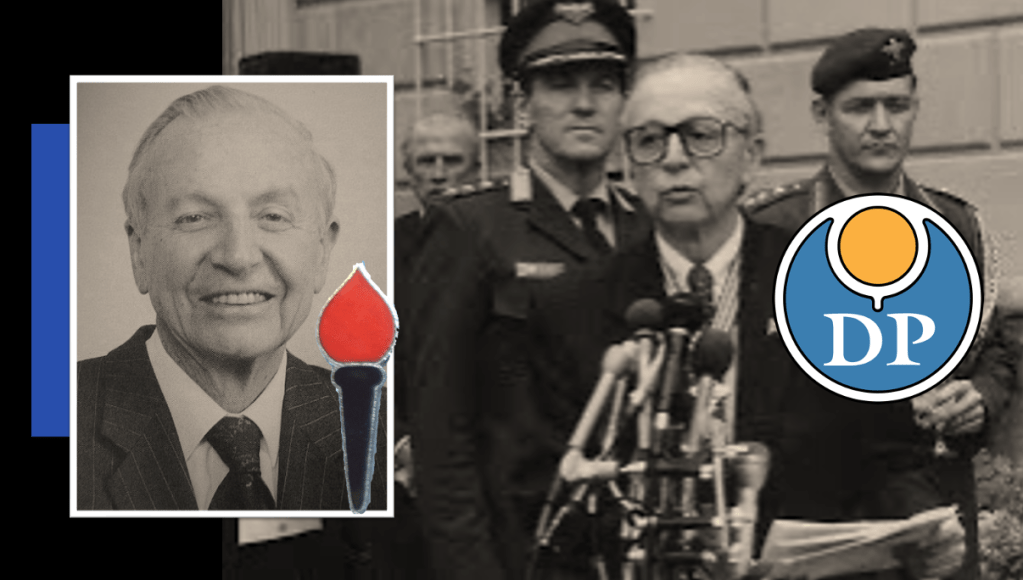

Joe Slovo ultimately becomes the General Secretary of The South African Communist Party and plays a key-pin role in South Africa’s future democracy when he brokers the ‘Sunset Clause’ for The National Party government which paves the way to a negotiated and democratic settlement for South Africa.

In 1991, Slovo returned to South Africa and joined the African National Congress’ (ANC) National Executive Committee and served as an SACP representative on the National Peace Committee dealing with constitutional principles and a constitution-making body and process.

After the 1994 elections Slovo was elected to the South African cabinet where he served as Minister of Housing (implementing the RDP housing program) until his death in 1995.

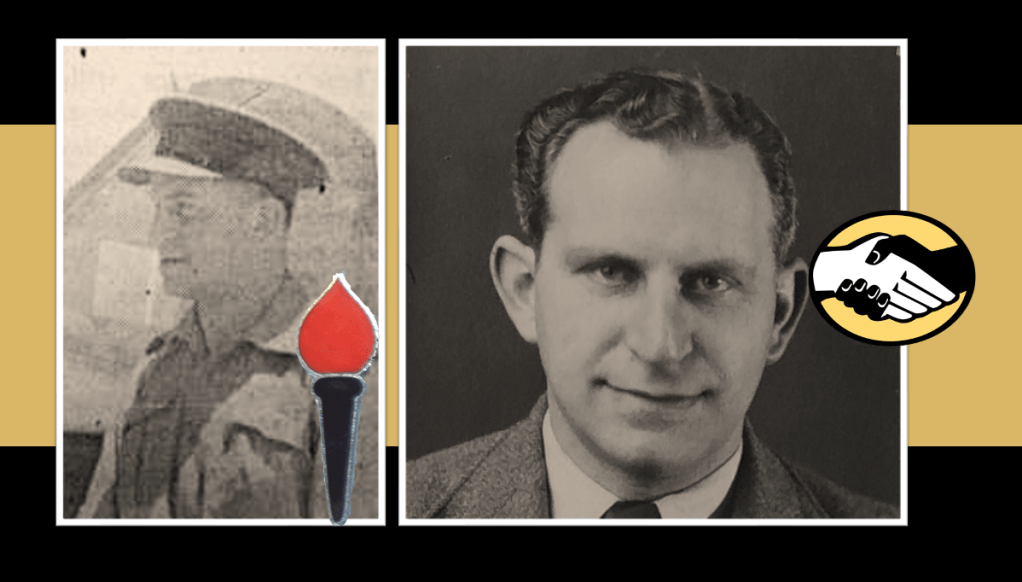

Fred Carneson

Fred Carneson, volunteers at the on-set of World War 2, joining the South African Army as a as radio officer initially in the East Africa campaign, by the time North Africa campaign comes around he is a hardened desert combatant and is badly injured at the Battle of El Alamein. He joins the Springbok Legion after the war and plays a pivot role in The Torch Commando when it is formed.

Fred Carneson is associated with the Treason Trial and acquitted, his Communist leanings then lead him to join uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) as a Political Commissar. Like, the Hodgson’s and the Slovo’s he and his wife Sarah form an anti-apartheid team.

He is arrested by the state police for breaking his banning orders whilst working as an editor on the New Age newspaper. He is tortured and kept in solitary confinement for 13 months, after which he is imprisoned at Pretoria Central Prison for nearly 7 years. Released in 1972 he goes into exile in the United Kingdom (UK).

In the UK he again became active in the South African Communist Party (SACP) raising funds for the SACP and ANC, eventually becoming the Chairman of the Anti-Apartheid Trade Union Committee. He passed away in South Africa in 2000.

The Liberals

Within the Torch Commando we find members who form the Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA). The epicentre for the establishment of the Liberal Party is literally traced to the “Coloured Vote” Constitutional Crisis and the resultant divisions within the Torch Commando.

Some of these Liberals, like their Communist colleagues, would ultimately strive for an armed resistance campaign against Apartheid whilst others who, like their Democrat and Federalist colleagues, would strive for a socio-political resistance campaign against Apartheid.

Unlike the mainstream Democrats, some of these ‘Liberal’ members are subject to same detention, banning and exile actions that the Communists are subjected to. The only difference between the two, they hold Liberal values and not Communist ones. Values that differ vastly from one another and clear to any Liberal or Communist, but not so clear to the National Party who merely lumped them in the same boat under their definitions in the anti-Communist Act. So, who are they?

Jock Isacowitz

Jock Isacowitz joins the South African Army during the war and rises to the rank of Warrant Officer. Highly politicised he becomes the National Chairman of the Springbok Legion after the war and is one of the guiding forces behind the establishment of The Torch Commando. Initially a member of the Communist Party of South Africa, when the Torch collapses, he becomes a Founding Member of the Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA).

He would become the Transvaal Chairman of the Liberal Party and eventually the Party’s National Vice-Chairman. Recognised as a threat to the Apartheid government, he was banned for two years and during the Sharpeville police sweep in 1960 he was detained for three months. He passed away shortly afterwards in 1962.

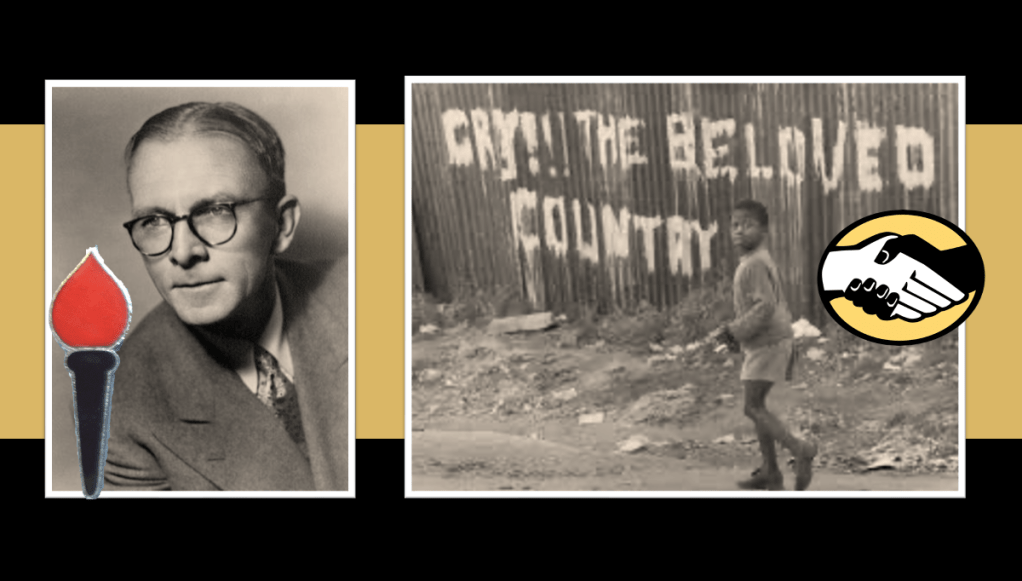

Alan Paton

Alan Paton, the famous author of ‘Cry the Beloved Country’ and leading anti-apartheid Liberal. Prior to World War 2 in 1938 Paton was the principal of an African boys’ reformatory at Diepkloof – and being completely bi-lingual – fluent in Afrikaans and considering himself a son of Africa. He gets swept up in Afrikaner Nationalism, grows a Voortrekker beard and joins the 1938 Centenary of the Great Trek on one of the wagons dressed as Voortrekker. As discussed in Part 1 The Nazification of the Afrikaner Right this Voortrekker centennial is pivotal to the advent of Nazism on a large scale in South Africa and the resultant domestic armed resistance to South Africa’s war efforts. At the closing celebrations of the 1938 Centenary Great Trek outside Pretoria, what awaited Alan Paton would change his perspective on Afrikaner Nationalism forever, of his epiphany he said:

“We arrived on a hot day, and I went straight to the showers. Here I was greeted by a naked and bearded Afrikaner who said to me, ‘Have you seen the great crowds?’ I said,’Yes’, He said to me with the greatest affinity: ‘Nou gaan ons die Engelse opdonder,’ (Now we’re going to knock hell out of the English).

The great day was full of speeches, and the theme of every meeting was Afrikanerdom its glories, its struggles, its grief, its achievements. The speaker had only to shout Vryheid (freedom) to set the vast crowd roaring, just as today a black speaker who shouts Amandla (power) can set a black crowd roaring. A descendant of the British 1820 settlers who gave Jacobus Uys a Bible when he set out on the Great Trek was shouted down because he gave his greetings in English as his forebear had done.

It was a lonely and terrible occasion for any English-speaking South African who had gone there to rejoice in this Afrikaner festival After the laying of the stone I left the celebrations and went home. I said to my wife: ‘I’m taking off this beard and I’ll never wear another. ‘ That was the end of my love affair with Nationalism. I saw it for what it was, self-centred, intolerant, exclusive.”

Although he was medically exempted from joining up when World War 2 broke out, Alan Paton would find himself a non-military member of the war Veterans’ Torch Commando in protest these very nationalists who staged this Centenary Trek and their accent to power in 1948.

An absolute adherent to Liberal values Alan Paton becomes the founder and leader of the Liberal Party, he remained the National President until the LPSA was dissolved in 1968 due to Apartheid legislation banning multi-racial parties.

In 1960 after returning from an award ceremony for the American Freedom Award, his passport was confiscated by the Apartheid government. It was returned only a decade later. Alan Paton would say of the Torch Commando and his time in it, that it was the Torch Commando movement the National Party only ever really feared.

Alan Paton died in Durban in 1988. The Alan Paton Centre and Struggle Archives at the University of KwaZulu-Natal now houses his papers as well as a major collection of apartheid-related manuscripts.

Leslie Rubin

Leslie Ruben at the onset of WW2 answers Smuts’ call and volunteers to join the South African Army in 1940, he is commissioned as a Lieutenant in the intelligence corps in north Africa, and later attached to the Royal Air Force in Italy.

After the war, he joins The Springbok Legion. He subsequently joined the Torch Commando, becoming a leading member within in the Torch’s Natal branch.

Along with Alan Paton, Leslie Rubin tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade Jan H. Hofmeyr, a leading United Party parliamentarian, to form a liberal party. After Jan Hofmeyr passed away in 1948, they went ahead anyway and created the Liberal party of South Africa (LPSA) in 1953.

Rubin became chairman of the Liberal Party in the Cape, and, in 1954, was elected to the Senate. As a Senator he fought every single Apartheid Legislation to the point that Dr Hendrik Verwoerd or on one occasion – the entire National Party caucus – walked out. Rubin resigned from the Senate in 1960 and went into exile.

In exile he became the chairman of the United States committee of the Defence and Aid Fund, getting funds to South Africa to support political prisoners and their families. He passed away in 2002.

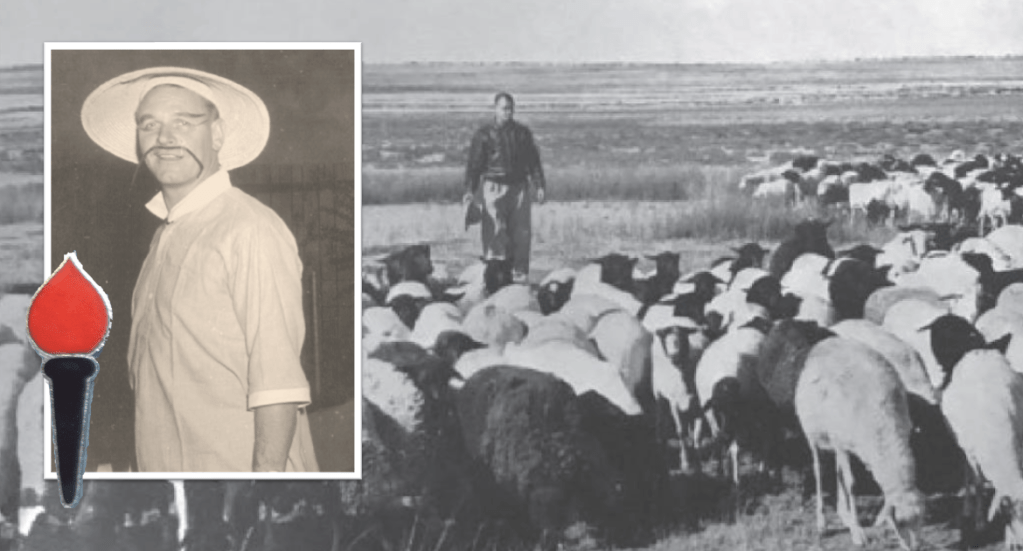

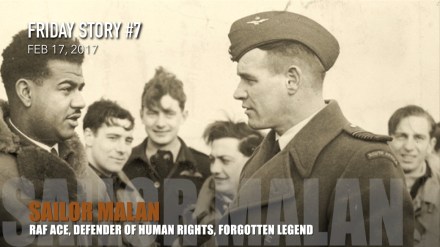

Sailor Malan

Sailor Malan, the President of the Torch Commando, also held liberal values, so much so it did not stop Alan Paton, Margaret Ballinger and Donald Molteno, from persisting that Sailor Malan (as a powerful potential political ally) join the Liberal Party of South Africa. In June 1953, Leslie Rubin would be tasked by the party to put pressure on Malan to join the Liberal Party.

However, with demise of The Torch Commando, Sailor became increasingly focused on his private life seeking serenity sheep farming near Kimberley. For Sailor, the stress of combat and political struggle had led him to say “my nerves are shot” – little did he know, now in his early 50’s, that he had rapid on-set Parkinson’s disease, a neurological disorder some believe triggered as the result of combat stress and the resultant PTSD.

He kept his distance using farming as an excuse not to join the Liberal Party, when pressed for a commitment by the LPSA “to forget your sheep for a little while”. According to the historian Bill Nasson Sailor Malan’ revealed that his reluctance was due to his gradualist conviction that the Liberals were going about things in the wrong way in making a fuss about franchise rights. As Nasson records

“The difficulty of selling it to white South Africans was by no means the least of his reservations. What the country needed was planned evolution. In his view, as he told Rubin, “more emphasis should be placed on economics and less on political rights. It is true that you are today dealing with the more educated Non-Europeans but your concern should be with the masses, to whom a full stomach and a secure life are more acceptable.”

Sailor Malan was very prepared to accept the inevitability of Black African majority rule, he felt the Liberal Party was too focused on black elites and lofty liberal values and not on the needs of the masses. Sailor Malan emphasised addressing “poverty and starvation”, with the primary emphasis falling on “material advancement”, the centre of which should be “very largely the economic advancement and housing of the African”.

In an odd sense Sailor Malan 1953 held the same view that modern Black African politicians hold now, that economic emancipation should precede political emancipation and without empowerment the ‘vote’ becomes meaningless.

Sailor Malan would not join the Liberal Party, nor any Party for that matter – a United Party seat was always open to him anytime he wanted it. Instead he chose to step back from politics after the Torch Commando collapsed and focussed on his private, family life, and having a little fun. Given Sailor’s history people always view him as serious, driven and focussed, but he loved a party and would often lighten them up, his socialising time spent in his Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH) Shellhole in Kimberley and the Kimberley Club (who have a plaque to him at the entrance).

Unfortunately his Parkinson’s disease was misdiagnosed at one point and he was told he would recover, and he rather enthusiastically reflected that finally he could start living, but it was a false sense of hope, Sailor Malan would pass away on the 17th September 1963, aged just 52. In what is arguably the lowest point a government can stoop to for a war hero of Sailor’s magnitude, the National Party declined requests for a formal military funeral, forbade any South African Defence Force members from wearing their uniforms to the funeral and from laying wreaths as military representatives, they specifically forbade the South African Air Force from laying a wreath. The government issued obituary for Sailor Malan circulated nationally contained no reference to his political career whatsoever, simply put the government wanted his memory wiped and nobody making a hero out of him.

In defiance to the National Party and to send a clear message to them, the governments of the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Rhodesia sent uniformed personnel and wreaths to Sailor’s funeral.

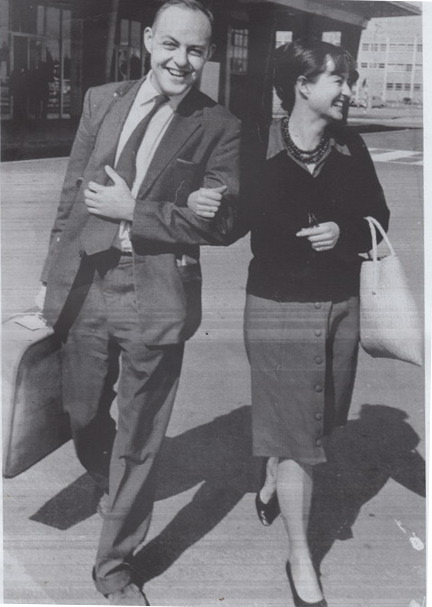

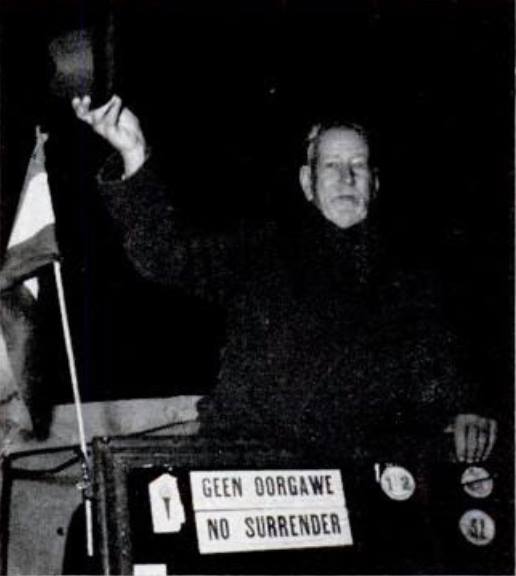

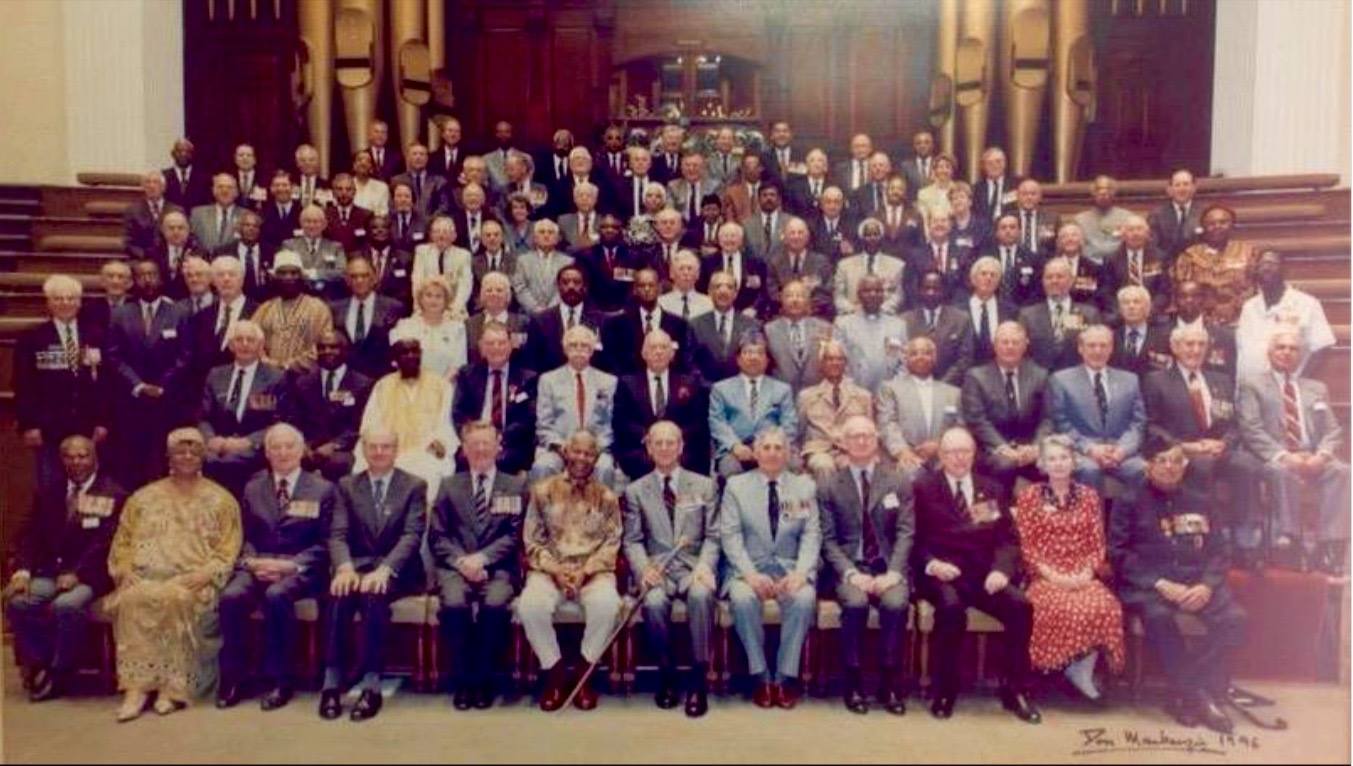

Image: Here Wing Commander J Moss of the Royal Rhodesian Air Force pays his tribute to Sailor Malan. It also did not stop the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), of which Sailor was a member from giving him the rites afforded a MOTH member. Behind Wing Commander Moss stands MOTH Francis John Dressler, a fellow WW2 vet, with the MOTH flag over his arm and a Brodie helmet (Tin Hat) in hand – the MOTH flag was subsequently draped over the coffin. As per MOTH ritual a candle would have been placed on the helmet and lit as a flame of remembrance.

At the very least his comrades in arms could afford him a privilege his own country refused to do. This injustice was finally corrected in 2023 on the 60th anniversary of Sailor Malan’s death, when in Kimberley the South African Air Force Association laid a wreath to him.

Peter Brown

Peter Brown joined the 6th South African Armoured Division during WW2. He would go on to become Alan Paton’s right-hand man and a kingpin of Liberal politics in South Africa. He is worth mentioning as he does attend a Torch Commando meeting and chooses not to join the Torch as he finds the organisation too ‘white’ and too ‘hierarchal’ for him.

In establishing the Liberal Party with the likes of ex-Torch members Rubin, Paton and Isacowitz in 1953, they target the Torch Commando and its now unbundling membership for a more robust LPSA membership. Ronald Morris, the Chairman of The Torch Commando’s Point Branch in Natal is a significant case in point – he would contest the Natal Provincial elections as a Liberal Party candidate.

Peter Brown would become embroiled in a Liberal Party spin off armed resistance movement called ARM (more about ARM later) and he would like so many LPSA members also go into exile.

David Pratt

One of the defining moments in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa was the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960 and its aftermath.

On the Liberal Party front political resistance was about to take a nasty turn, when in April 1960 – 19 days after the Sharpeville Massacre, Prime Minister H.F. Verwoerd, the architect of Apartheid was giving his ‘good neighbourliness” speech at the Rand Show in Johannesburg.

After Verwoerd gave his opening speech, he returned to his seat in the grandstand where he was shot at point-blank range by David Pratt, who was an outspoken Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA) member and a wealthy English farmer from the Magaliesberg region outside of Pretoria. He joined the Liberal Party in 1953 and believed that a coalition between liberals and ‘verligte’ (enlightened) Afrikaners was the only solution to defeating the National Party at the polls. Verwoerd survived Pratt’s attempted assassination of him, only to be finally assassinated by Dimitri Tsafendas, a white man with Communist leanings, on the 6th September 1966.

Pratt was also an epileptic with a long medical history of heavy epileptic fits – so he was excused military service and did not join The Torch Commando. So to dismiss Pratt as a ‘lunatic’ – as to the Nationalists no white person in their right mind would shoot a white Prime Minister – so he was judged as ‘insane’. Pratt was sent to an institution for the mentally ill and by October 1961 he was found – rather too conveniently for the Nationalist government – hanging from a rolled-up bed-sheet.

John Lang

John Lang joined the Navy for World War 2 but did not aspire to any senior rank, he is a qualified lawyer post war and his political and resistance career starts as when he takes up a ‘strong-man’ security role for The Steel Commando protest (the show of strength in Cape Town to oust the National Party and force them to resign). He also joins the Torch Commando’s national executive.

When the Torch Commando collapses, John Lang tries to revive The Torch Commando in 1955 and through the Torch becomes a key member in The Liberal Party. He is a key force when the Liberal Party branch is established in Johannesburg in co-ordination with the Natal committee. He also raises significant funds for The Liberal Party at its onset. As an attorney Lang becomes embroiled in a trust fund scandal, he however remains a key figure within the Liberal Party as a fund raiser.

John Lang is a significant character in our tracing of the Golden Thread of ‘white’ political and armed resistance it’s smoking gun, the Torch Commando, and like all things in the South African armed ‘struggle’ his story really kicks off with Sharpeville Massacre.

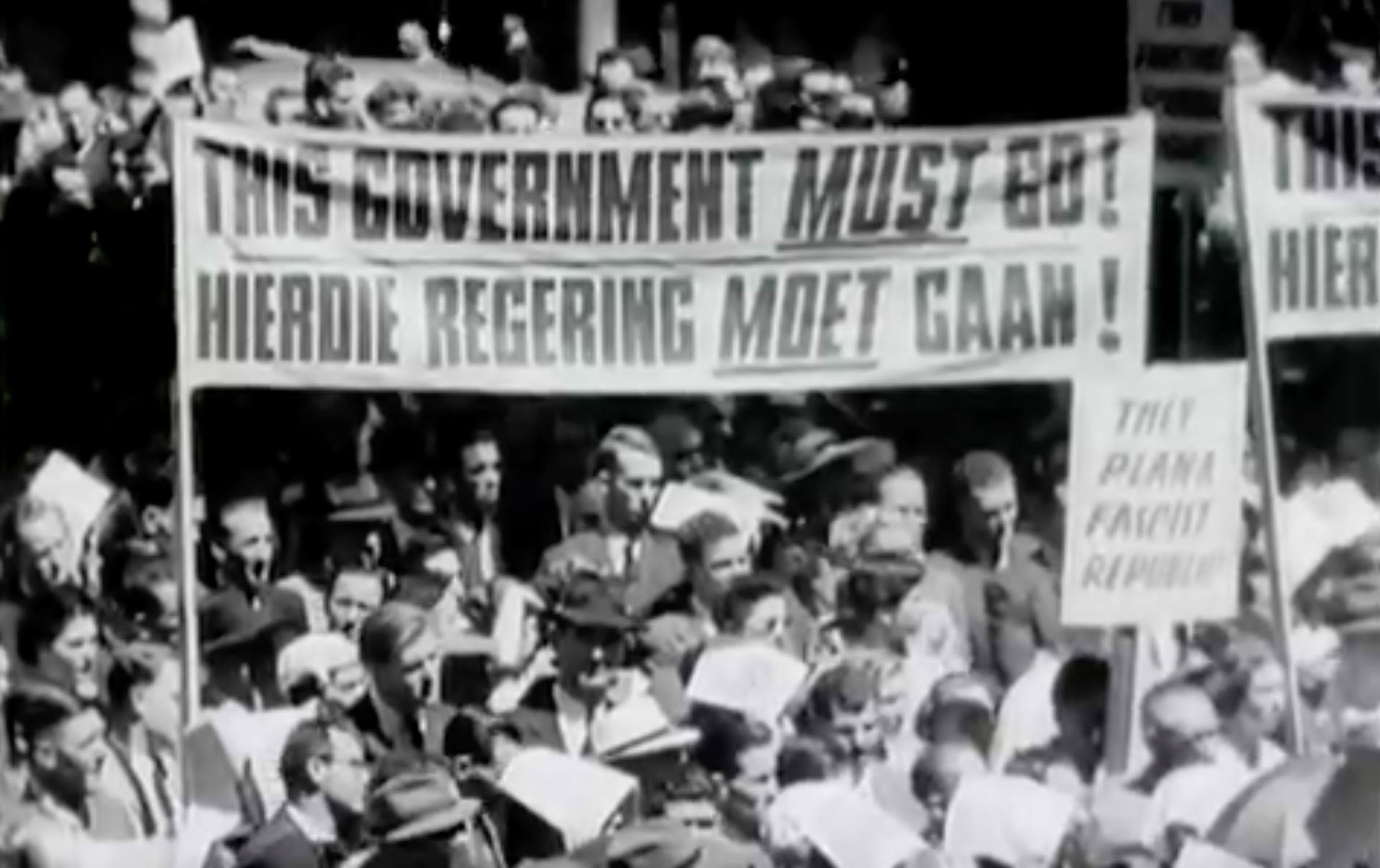

The Sharpeville Massacre occurred on 21 March 1960, after which a state of emergency was declared, the African National Congress (ANC) and Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) were banned and forced underground. Liberation movements were forced to re-evaluate their approach to the liberation struggle and consider non-violence in favour of military sabotage.

Despite the Liberal Party’s initial non-violent stance, the party was not spared the suppression of its political activity by the Apartheid State. The legislative tool used to crush the Communist Party, Springbok Legion, Torch Commando and the Liberal Party was the Suppression of Communism Act 44 July 1950. The Act’s name was misleading as it was a sweeping act and not really targeted to Communists per se, it was intended for anyone in opposition to Apartheid regardless of political affiliation. The Act defined “any scheme aimed at achieving change whether economic, social, political, or industrial – by the promotion of disturbance or disorder or any act encouraging feelings of hostility between the European and the non-European races…calculated to further (disorder)”.

With the powers of the State of Emergency and the Suppression of Communism Act, the Apartheid State also launched a vicious attack on the Liberal Party, arresting 35 of its leading members in 1961, including John Lang and detaining them at the Fort in Johannesburg.

Whilst imprisoned in the Johannesburg Fort prison John Lang makes contact with fellow Liberal Party members Monty Berman (also a South African WW2 military veteran of the Italy campaign where he is exposed to Partisan warfare) and Ernest Wentzel who are also swept up in the Sharpeville clampdown and between them they establish the National Committee for Liberation (NCL) and embark on an armed struggle of their own.

The NCL declares itself as an armed struggle movement of ‘Liberals’. The NCL challenges the idea of peaceful protest when the government was evidently intent on using violence. The NCL is formed under a liberal ideological framework, declaring an armed struggle on the proviso that no human life is harmed. Ironically the formation of the NCL pre-dates the formation of MK but the official announcement of its existence occurs on the 22nd December 1961 a couple of days after MK announces its existence on 16th December.

This white ‘Liberal’ armed resistance, like MK, was going to need money to buy arms and explosives – and as a fund raiser John Lang was up to the task. After his release from prison, Lang immediately forms a secretive NCL cell which eventually becomes known to the South African Police Intelligence Services as ‘The Group’. The objective of The Group a.k.a. John Lang, is to obtain financial support for the NCL.

John Lane’s first mission is to make contact his old Torch Commando comrade and Liberal Party founder stalwart – Leslie Rubin (by now in exile) to source funds from the Ghanaian government – which were given in two financial payments in 1961 (NCL was the first armed resistance group to get finance from Ghana). With money to buy weaponry and explosives the NCL were now ready to go.

The NCL’s armed Resistance campaign

The NCL was non-racial although its membership was predominantly White. The organisation hoped to attract an African following by acts of sabotage against government installations and institutions.

The NCL attracted three groups of ‘Liberals’ to its ranks: members of the Liberal Party (the largest grouping), the African Freedom Movement (AFM) – made up of disillusioned ANC members not joining MK, and the Socialist League of South Africa (SLA) – made up of disillusioned South Africa Communist Party (SACP) members – ‘Trotskyites’ who also did not want to join MK and its SACP alliance.

Regional Committees of the NCL were to operate autonomously. Between 1962 and 1963 the NCL focused on recruiting – Adrian Leftwich of the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) joined the organisation, so too Randolf Vigne, the vice chairman of the Liberal Party, joining after he was recruited by John Lang.

Other members included Neville Rubin, Baruch Hirson, Stephanie Kemp, Lynette van der Riet, Hugh Lewin, Ronald Mutch, Rosemary Wentzel, Dennis Higgs and Alan Brookes. Most of them from the Liberal Party. The NCL established two regional committees – Cape Town and Johannesburg but also had a cell in Natal, notably David Evans and John Laredo.

The NCL initially involved itself with smuggling people out of South Africa into exile, this included helping the ANC smuggle Robert Resha into Botswana. The ANC reciprocated by helping Milton Setlhapelo of the NCL move from Tanzania to London.

With a sense of combined purpose the NCL leaders endeavour to join hands with MK, the NCL approached MK through Rusty Bernstein (remember our old Torch Commando stalwart who becomes a founding member of MK – see the Torch’s Communists) to organise joint operations. After one failed operation the two organisations ceased to cooperate again.

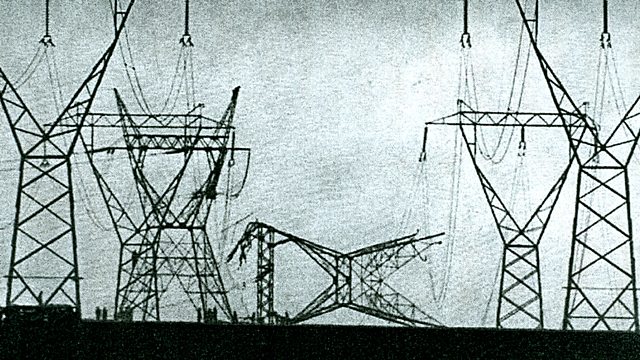

NCL Military Operations

Late 1961 the NCL sabotage campaign commenced with the targeting of three power pylons and the burning of a Bantu Affairs office.

By 1962, dynamite was stolen from mines. Dennis Higgs and Robert Watson, a former British Army officer, provided explosives training to members of the NCL in Cape Town and Johannesburg. In August and November 1962, the NCL carried out sabotage attacks on pylons in Johannesburg, bringing one down.

In Durban, the members of the NCL failed to bring down a electricity pylon as a result of faulty timers. Later, in August 1963, the NCL made two attempts to sabotage the FM tower in Constantia, Cape Town. On the first attempt, the operation was cancelled after Eddie Daniels lost his revolver, which was found a few days later. In the subsequent operation at the same installation, the bomb failed to explode.

Later, in September, explosives damaged four signal cables at Cape Town railway station, and in November an electricity pylon was brought down.

ARM

Given their declared intentions of armed resistance the NCL became wanted by the Apartheid State, Myrtle and Monty Berman were banned and in 1961 the police searched John Lang’s residence where letters requesting financial assistance were seized.

On 26 June 1961, John Lang fled South Africa and went into exile to London, where he continued with anti-apartheid activities on behalf of the NCL. That same year, Monty Berman violated his banning order and was given a three-year suspended sentence. As a consequence, he was forced to leave the country in January 1962. His departure threw the NCL into disarray, and morale among the remaining members declined.

The NCL’s efforts to revitalise itself without its leaders on the ground in South Africa failed and to reinvent itself, the organisation changed its name from the NCL to the African Resistance Movement (ARM). ARM launched its first military operation in September 1963.

From September 1963 until July 1964, the ARM bombed power lines, railroad tracks and rolling stock, roads, bridges and other vulnerable infrastructure, without any civilian casualties. ARM aimed to turn the white population against the government by creating capital flight and collapse of confidence of the economy.

In Johannesburg, a cell of the ARM also carried out more attacks in September and November 1963. NCL members used hacksaws to cut through the legs of a pylon in Edenvale, which led to a blackout in Johannesburg’s eastern suburbs. More attacks on pylons were carried out in January and February 1964. The climax of the ARM campaign came in June 1964 when five pylons were destroyed; three around Cape Town and two in Johannesburg. In fact some sources say that ARM was more active in this period than MK.

On 12 June 1964 ARM issued a flyer by way of a statement announcing its existence and committed itself to fighting apartheid and it read in part:

“The African Resistance movement (ARM) announces its formation in the cause of South African freedom. ARM states its dedication and commitment to achieve the overthrow of whole system of apartheid and exploitation in South Africa. ARM aims to assist in establishing a democratic society in terms of the basic principles of socialism. We salute other Revolutionary Freedom Movements in South Africa. In our activities this week we particularly salute the men of Rivonia and state our deepest respect for their courage and efforts. While ARM may differ from them and other groups in the freedom struggle, we believe in the unification of all forces fighting for the new order in our country. We have enough in common.”

John Harris

The end of ARM begins with Frederick John Harris –a member of the executive committee of the Liberal Party in the Transvaal and the Chairman of the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee. He lobbies and is partly accredited for South Africa’s ban from the Olympics in 1964. His ‘liberal’ actions earned him a banning order and by February 1964 he was recruited and joined ARM. He decided that a dramatic gesture was needed to “bring whites to their senses and make them realise that apartheid could not be sustained”.

On July 24, 1964, John Harris walked into the Johannesburg railway station and placed an explosive charge and several containers of petrol in a suitcase on the main ‘whites only’ concourse. On the case he left a note: “Back in 10 minutes”

Despite a pre-planned detailed telephone warning to the Railways Police and targeted newspapers to evacuate the station, no action was taken. The bomb exploded, injuring several people seriously, in particular Glynnis Burleigh, 12, and her grandmother, Ethel Rhys, 77. Mrs Rhys who died three weeks later. Glynnis, who had 70%- and third-degree burns, was left with life-changing injuries.

The ARM action produced a horrified reaction amongst the white population – ARM had finally killed an innocent civilian despite their Liberal values. The incident was incorrectly touted by the National Party as part of a terror plot by “Communists” (not liberals). Harris was arrested, tortured and beaten. His jaw was broken in three places.

Harris was tried for murder of a civilian and by the tenets of South African law for murder received an automatic death sentence (despite attempts at an insanity plea and a ‘manslaughter’ plea). His friends and family believe to this day that the Sate was never going to allow John to beat the rope.

On April 1, 1965 went to the gallows, reportedly singing “we shall overcome”. His remains were never handed to the family – they disappeared. A heart-breaking private investigation after 1994 found them in a prison cemetery – simply marked ‘John Harris’ – the words ‘A Patriot’ were added later to his headstone by his family. His legacy as the only ‘white’ man to be hanged for ‘crimes against Apartheid’ as lost to the history of the struggle as his headstone was.

The end of ARM

After the bombing in July 1964 the police raided the flat of Adrian Leftwich and subsequently raided the flat of Van der Riet, finding documents containing instructions on sabotage and the storage of explosives. Under torture and interrogation, the two implicated their comrades.

Leftwich’s statements were devastating for ARM. He testified against his comrades in at least two of the trials, and as someone who had played a key role in NCL/ARM operations, his evidence was difficult to refute. Subsequently, the police raided and arrested 29 members of ARM, among them Stephanie Kemp, Alan Brooks, Antony Trew, Eddie Daniels and David de Keller – all in Cape Town. Others like Randolf Vigne, Rosemary Wentzel, Scheider, Hillary Mutch and Ronnie Mutch escaped.

The security police kidnapped Wentzel from Swaziland and brought her back to stand trial in South Africa. She sought relief for her illegal abduction through the courts. Dennis Higgs was also kidnapped by apartheid government forces and challenged the legality of his kidnapping through the courts.

In the subsequent trials, Eddie Daniels was sentenced to 15 years in prison, which he served on Robben Island. Baruch Hirson was sentenced to nine years in prison, Lewin to seven years, while Evans and Laredo were sentenced to five years in prison. David De Keller received a sentence of 10 years, Einstein seven years, Alan Brooks four years, Stephanie Kemp five years, and Anthony Trew four years.

The arrest of ARM members and the flight of others into exile led to the disintegration of the organisation.

However, some of its members, particularly those in exile, continued fighting against apartheid by working for anti-apartheid organisations. Hugh Lewin was appointed head of the International Defence and Aid Fund’s (IDAF) information department. Rundolf Vigne also worked closely with IDAF in Britain and travelled to the United Nations (UN), campaigning against the apartheid government. Finally, Alan Brookes, a former member of ARM played a key role in organising demonstrations against the 1969 Springbok Tour to the UK.

A little raw – still

Myrtle Berman and the others never really come to terms with the bombing and killing of a human being and the trauma of the hanging, it counter acts their Liberal values and the stated objective of ARM.

The late Adrian Leftwich describes his behaviour as “shameful, harmful and wrong” and although repentant and his actions the result of unimaginable torture in jail, his status as a ‘sell-out’ still sticks.

Modern attempts to revitalise the Liberal Party do not even account this ‘armed struggle cred’ as part of their history – it’s that disconnected to the modern narrative of Liberalism in South Africa.

The End of the Liberal Party

Sharpeville signals the of the Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA), but its demise starts earlier with a sustained persecution of Liberal Party members by the Nationalists.

In 1962, BJ Vorster opened the shots at the LPSA when he accused the party of being nothing more than a “communist tool”. This opened the way, as between March 1961 and April 1966, 41 leading members of the LPSA were banned under the Suppression of Communism Act.

By 1965, leaflets were secretly scattered by government agents warning African members of the Liberal Party that they would be banned unless they desisted.

The state would continue to harass and intimidate Liberal Party members. Security branch officers would attend party branch meetings. The police would intimidate families of party members, even Alan Paton had his telephone lines tapped and house was searched.

In 1966, the government tabled the Prohibition of Improper Interference Bill, which proposed the prevention of interracial political participation. In 1968, the Bill was passed in parliament as the Prevention of Political Interference Act. Two political parties, the Progressive Party (PP) and Liberal Party had members across racial line were severely affected.

The PP chose not to disband but become a white’s only party to fight Apartheid via the legal parameters available to it and be a representative voice of the disenfranchised in a now dominated Nationalist Parliament.

The Liberal Party chose to disband rather than comply with legislation that went against its defining principle of non-racialism. Between April and May 1968, meetings were held in various parts of the country, bringing an end to the Liberal Party’s 15 years of anti-apartheid struggle.

The Democrats

The Democrats form the backbone of socio-political resistance to Apartheid without engaging an armed resistance campaign – attempting to work within the confines of ever-increasing National Party’s political gerrymandering and jack-boot legislative repression.

As we have established, The Torch Commando is not all about these fire-brand Communist war veterans joining MK in ‘armed resistance’ to Apartheid. It’s a mixed bag of Liberals, Federals and Democrats in addition, so who are they and what do they do when the Torch collapses? Let’s have a look at the Democrats – the ‘Progressives’ and their ‘political’ resistance to Apartheid;

Harry Schwarz

Harry Schwarz joins the South African Air Force during the war as a Observer (navigator and bomb aimer) – part of 15 Squadron “Aegean Pirates” fighting in North Africa and Italy. Harry Schwarz is a co-founding member of The Torch Commando after the war and takes a key role in Torch Commando’s anti-apartheid stance. He joins the United Party however; he becomes disillusioned with United Party the party’s appeasement politics to woo back white UP voters now supporting the National Party.

He is expelled from the United Party with the ‘Young Turks’ rebellion. Following this he plays a pivotal role in the formation of the Reform Party (RP) and is elected as its leader. The party’s charter calls for full franchise and equal rights for all. In 1975 the Reform Party is fused with the Progressive Party, led by fellow ‘UP Young Turk’, WW2 veteran and Torch Commando member, Colin Eglin (remember, there is a ‘golden thread’ weaving its way through this history).

The merger forms the Progressive Reform Party (PRP) with Colin Eglin at the helm. As Smuts’ old United Party continues to disintegrate, the PRP takes on more of the progressive old UP members and the PRP evolves into the Progressive Federal Party. Harry Swartz continues in a long-time opposition to Apartheid aas a leading figure in the Progressive Federal Party and continues in opposition to Apartheid when the PFP finally as it morphs into the Democratic Party (DP) – the precursor to the modern-day Democratic Alliance (DA).

After the ANC is unbanned, in 1991 Harry Schwarz becomes the first opposition member to the National Party to be appointed Ambassador to the USA – a controversial appointment Harry Swartz seeks permission before he takes it – it comes in his old Torch Commando friend, Joe Slovo (there is that ‘golden thread’ again) and Nelson Mandela in addition to give him the nod – and he takes the appointment.

During his appointment as Ambassador to the USA, he negotiated the lifting of US sanctions against South Africa, secured a $600 million aid package from President Clinton and signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1991 officially ending South Africa’s armed nuclear program developed during the Apartheid era. He died in South Africa in 2010.

Colin Eglin

Colin Eglin joins the 6th South African Armoured Division in Italy during WW2. He takes an intelligence role as a Corporal whilst serving in combat operations in the Italian mountains. After the war the “Egg” as he is nicknamed cuts his political teeth when he joins The Torch Commando.

He also joins the United Party (UP) and formulates a relationship with Zach de Beer. In 1959 he joins the ‘Young Turk” rebellion in the United Party, like Schwarz he is dissatisfied with their appeasement politics to the conservative white voting base.

He was one of the 11 UP members of parliament who formed the nucleus of the newly established Progressive Party (PP). By 1966 he is the Progressive Party’s Chairman and by 1971 the Party Leader. He negotiates the merger with the RP with his old Torch Commando chum, Harry Schwarz in 1975. Following the dissolution of the UP, some members were co-opted by his party, and the PRP became the Progressive Federal Party (PFP). In 1986 he was re-appointed chairman following the resignation of Van Zyl Slabbert, he was the PFP’s Party Leader until 1988 when his old friend Zac de Beer took over the leadership.

Eglin is instrumental in the merger of the Independent Party and National Democratic Movement with the PFP to bring about the Democratic Party in 1989 and was elected chairperson of the DP’s parliamentary caucus. He would also play a key role in founding The Red Cross Children’s Memorial Hospital (financed by World War 2 veterans as a ‘living’ memorial).

The ‘egg’ is a life-long anti-Apartheid campaigner – he remains with the DP when it morphs into the modern-day Democratic Alliance (DA) and he finally retires from Parliamentary politics in 2002. He passed away in 2013. For more on the ‘Egg’ and his military service follow this link: A road to democracy called ‘the egg’!

Dr Jan Steytler

Dr Jan Steytler was decorated for gallantry while serving with the UDF Medical Corps in the Western Desert and held the rank of Captain, disillusioned with the United Party he would also lead the breakaway and form the Progressive Party. He would be named as the first leader of the Progressive Party when it was founded on 13 November 1959.

Jan Steytler is regarded as one of Apartheid’s most vocal critics. Gradual restrictive Apartheid legislation, silencing and gagging orders, gerrymandering and media bans of the Progressives in Parliament as official opposition, would ultimately lead to them all losing their seats, with the exception of Helen Suzman being the only one – standing as a lone voice of opposition to Apartheid in Parliament for 13 long years.

Although Jan Steytler did not join the Torch Commando, he had a close connection to The Torch, his brother William Steytler who also broke away from the UP and joined the PP, had served as a lieutenant in the Army and he was the Chairman of the Torch Commando – Burgersdorp branch.

The United Federal Party

The United Party’s loss of the 1953 General Elections and the collapse of the Torch Commando in its wake leaves a vacuum from which both the Liberal Party and the Union Federal Party are formed, as ex-servicemen in the Torch Commando pursue their respective political faults in opposition. It is an absolute truism in every respect to say that both these parties are literally formed within the Torch Commando.

So, what is the difference between these two ‘liberal’ parties – where is the political fault line?

Sir De Villiers Graaf of the United Party in particular and the party in general was trying to toe a moderate ‘centreline’ politics bridging Apartheid right-wing leaning politics and Liberal left-wing politics into balance – and in fact had taken a more robust and antagonistic approach to the liberal wing of the party. The 1953 elections left the ‘Liberal’ end of the party in need of its own vehicle of political resistance.

A liberal alliance, the South African Liberal Alliance (SALA) was formed In January 1953 to map a route forward, three Torch Commando members see the SALA go in three different directions. Leslie Rubin would guide the formation of the Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA), Colin Eglin would eventually lead the ex-servicemen break from the United Party and form the Progressive Party, and finally, Geoffrey Durrant would paves the way to another party – The Union Federal Party (UFP).

So, what’s the difference between the UFP and LPSA? For starters the UFP is a little more moderate and its origins lie in ‘the Natal stand’, at the centre of its mandate is South Africa’s dominion relationship with Great Britain and the Commonwealth of Nations (appealing to many ex-servicemen having just fought to maintain these concepts), on race it stands for full enfranchisement of ‘Coloureds’ and ‘Indians’ and a gradual phased qualified enfranchisement for ‘Black’ natives.

The ‘black native’ position is not a usual one for 1953 given segregation was still been practiced world over. The ‘Native’ ethnic groups were generally left to their respective ‘kingdoms’ (the ex-protectorates in reality) to govern themselves along their traditional systems of monarchy governance, the real problem is an ever growing ‘Black’ urban proletariat class and the idea of even enfranchising it in 1953 is a very ‘liberal’ one.

After the 1953 election, most senior Torch Commando leaders in Natal are disillusioned with the United Party not taking a stronger stance on the constitutional issue of whether Natal should remain in the Union or break from it if forced into a Nationalist Apartheid hegemony bent on manipulating the constitution illegally (and eventually breaking with ‘Union’ and creating a Republic). These Natal Torch-men include Edward (Gillie) Ford, a SAAF officer taken POW during the war and his fellow torch-men, James Chutter, Roger Brickhill, Robert Hughes-Mason, Arthur Selby, James Durrant and William Hamilton from the Natal Torch’s Executive Committee – who all forged ahead into the Union Federal Party (UFP) which comes into being on 10 May 1953.

Given its Torch roots, it’s no surprise that the UFP, emulates the Torch’s position regarding the South African constitution and race relations. The South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR) traces the UFP’s position on race relations back to the Torch’s position on race relations i.e. the preservation of the constitution and the entrenched clause dealing with equal language rights for English and Afrikaans – this led the UFP to consider the other entrenched clause dealing with non-European voting rights, and to formulate a policy to promote racial harmony.

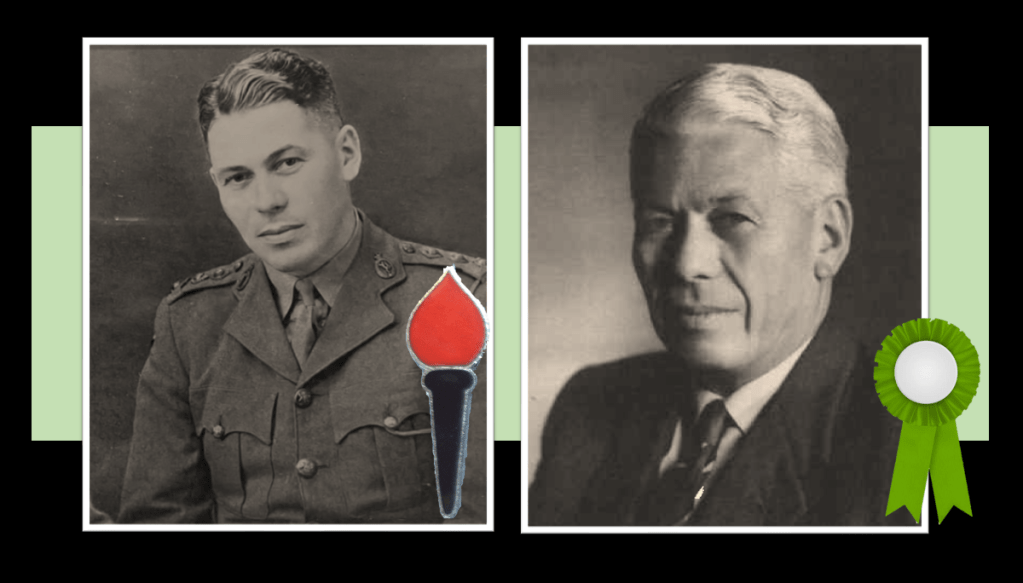

Although a full-time lawyer, and not really a politician, Louis Kane-Berman, the Torch Commando’s Chairman decides to throw in his support for the Federalist cause as opposed to the Liberal Party cause and becomes a member of the Union Federal Party. As to Kane-Berman’s legacy, John Kane-Berman, his son, would become a lifeline guiding light in Institute of Race Relations and Liberal Politics in South Africa.

The elected leader of the UFP was an ex-UP Senator George Heaton Nicholls, a well-respected and seasoned Natal politician, and also a military veteran, not of WW2 but of The South African War (1899-1902) a.k.a., Boer War 2.

Unfortunately, the UFP broad public appeal was very limited and as a party it did not exist for every long, its outwardly ‘British’ stand appealed to the white English electorate but alienated the white Afrikaner electorate who perceived it as jingoism. Up against the UP and the Labour Party (and even the Liberal Party) for the opposition vote, it simply did not have the groundswell and critical mass to win seats. It led a ‘NO’ Campaign in the 1960 National Referendum on whether South Africa should become a Republic. After that defeat, the Union Federal Party was dissolved as its ‘raison d’etre’ simply ceased to be after South Africa became a Republic.

Apartheid conditioning of white youth

Conscription of all white men into the South African Defence Force began in 1966 as the National Party feared a United Nations military action against South Africa over the 1966 Resolution deadline for an Independent SWA/Namibia which South Africa ignored (to the National Party the sympathetic ‘white voter’ block in SWA was still critical to their hold on power).

The National Party was in two minds about initiating conscription, one part felt that conscription was necessary to condition the future white youth to the ideals by which the Nationalists stood – Republicanism, Apartheid and Anti-Communism – and packaged this as the ‘Swart’ and ‘Rooi’ Gevaar (Black and Red Danger) respectively.

Some in the National Party were against conscription, the South Africa Defence Force after all the ‘Frans Erasmus Reforms’ had worked – the removal key of ‘English speaking’ and ‘Smuts’ officers had been completed, the rank structures and symbology changed to identify with the ‘Volk’, the old Boer ‘Commando Structure’ reinforced – so much so Defence Force was now considered a key ally of the National Party’s power base and vote. Bringing the ‘English’ speaking whites back into it on an equal footing again may destabilise it.

The external threats of the Communist ‘domino effect’ in Africa edging ever closer – in Angola, Mozambique and Rhodesia specifically – and the UN threat as to South West Africa (Namibia), along with escalating internal violence – the army needed a substantial human resource boost to maintain the status quo and the Nationalists also saw it as an opportunity to condition ‘all’ white youth to their cause, including the English speaking whites (and forcefully bring them onto their side so to speak).

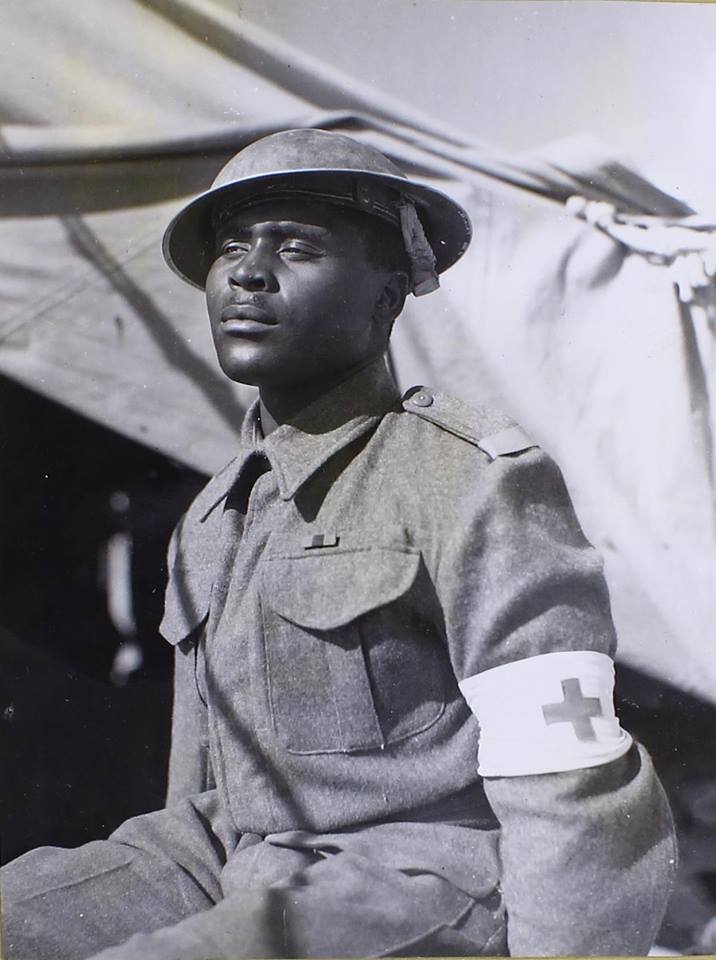

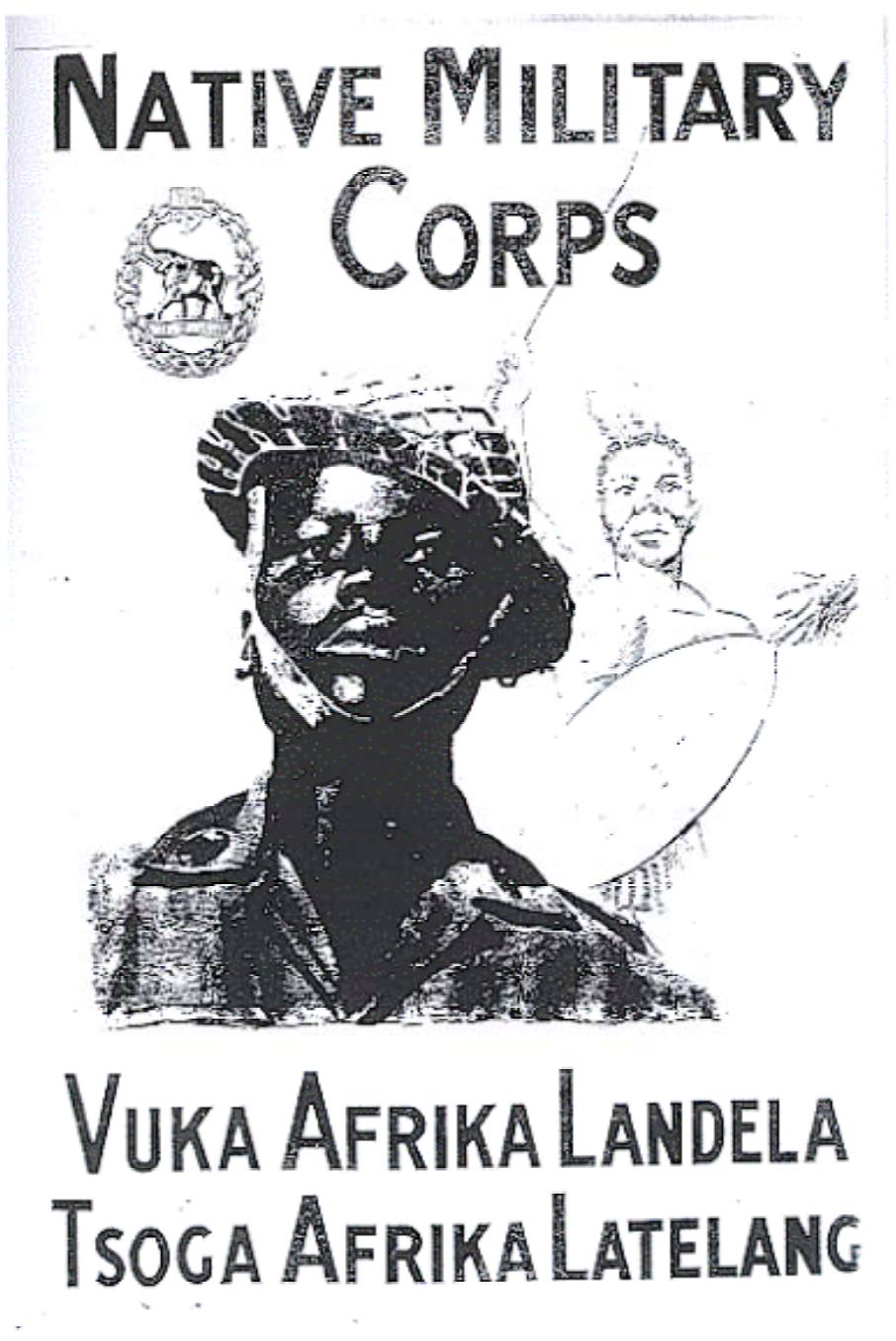

Added to this was the implementation of the National Christian Education Curricula at all levels of primary and secondary schooling funded by the state. This would see a Nationalist re-interpretation of all South African history along Afrikaner Nationalist lines. The State would also play a direct role in guiding all formal histories of The Second World War – a sanitised ‘white’ version of it would be taught, the role of the Native Military Corps (NMC), Cape Corps (CC – ‘Coloureds) and Indian and Malay Corps (IMC)largely written out of it.

The Nazi sympathies and terrorist actions during the war of leaders of the National Party would be removed – and the direct Nazi German collaborations by Ossewabrandwag (OB), SANP and New Order during the war would be wiped clean – the OB would be positioned as ‘anti-British’ because of the Boer War and nothing more. The OB intelligence and historical archive was slammed shut in 1948 by Frans Erasmus and although partially re-opened by ‘gate-keepers’ it was only fully re-opened as late as 2015 for all the proof on its full blown collaboration with Nazi Germany itself. The political reaction of the returning servicemen and The Torch Commando would also be wiped clean completely.

After years of military and education conditioning, sanitising of media, years of banning and/or gagging of white political opposition – to the majority of ‘white’ male youth and young white adults – both English and Afrikaans – by the 70’s and 80’s the National Party presented itself as the only way forward for ‘white’ survival in Africa in light of a “Total War” against the “Total Onslaught”.

Pesky Students

By the 1970’s almost every Political party and White political figures not in step with the National Party’s ideas of separate representation were imprisoned, in exile, banned or gagged. End of the ‘troublesome’ whites – not so!

From a military history perspective, one of the many threads of resistance comes where the NCL/ARM found Adrian Leftwich – the student movements, in the case of Whites – The National Union of South African Students (NUSAS).

The late 70’s and 80’s saw tens of thousands of White students from the ‘Liberal’ white dominated universities on active protest – Natal, Wits, Rhodes, UCT. Entering the fray are many academics and even a student culture music movement – the Voëlvry Movement (James Phillips, Koos Kombuis and Johannes Kerkorrel).

In NUSAS dominated Universities the End Conscription Campaign (ECC) found its bedrock. In fact the ECC took shape initially within NUSAS.

No shrinking violet, a case in point – in 1983, the ECC co-founder Brett Myrdal, publicly refused his call-up and elected to stand trial an spend his ‘2 years’ behind bars, in September 1983, three days before Myrdal’s trial the state increased prison sentences for objectors from 2 years to 6 years. Mydral goes into exile and joins MK instead.

Twists and Turns

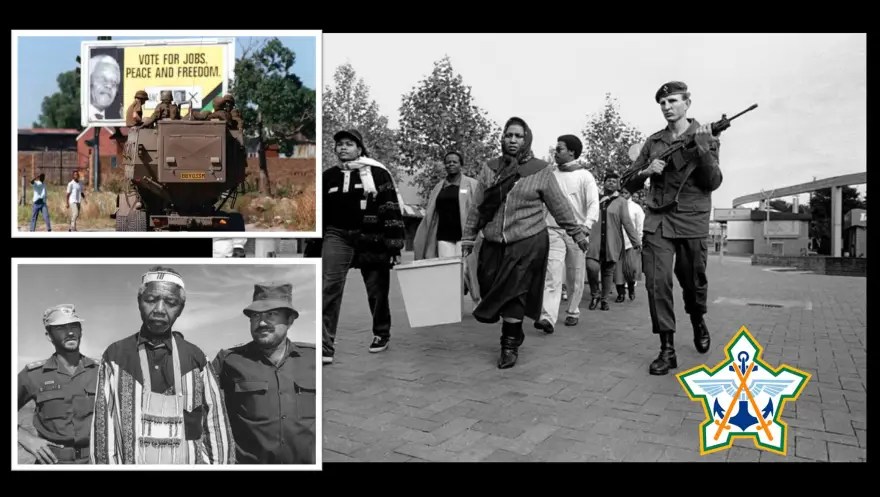

By 1990 the ANC is unbanned and the ’struggle’ landscape changes – especially for white South Africans. The Yes/No Referendum in 1992 gives voice to the silent majority of pro-democracy whites not heard from since 1948. It ensures that the final defeat of Apartheid becomes a moral one and not a military one.

The composite National Peacekeeping Force NPKF fails and CODESA calls to replace the force with statutory force SADF personnel. The battleground moves to the politically violent void between the African National Congree (ANC)/Inkata Freedom Party (IFP) and in the lead-up to democracy – in a deep irony the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), a white supremacy movement also embarks on a armed resistance campaign against the National Party Government and its CODESA collaboration – and in an ironic twist, thousands of white conscripts – those from the 80’s generation and post 1990 call-up take up the role of Peacekeeping in the SADF and transition the country to full democracy. This call up of the country’s reserves of white conscripts to their regiments in 1994 to secure the election is paradoxically supported by the ECC as a ‘different kind of call-up’.

In the end, the instrument of the new democracy – the vote itself – is secured by white military conscripts, not by any non-statute forces – an inconvenient fact in the contemporary narrative of ‘The Struggle’. The old National Party objective of conditioning many of these white conscripts to Afrikaner Nationalism proved null and void and in fact entirely baseless in the end.

To read more on these events leading to the elections follow this observation post link: The Inconvenient ‘Struggle Heroes’ of Freedom Day

The ‘fatal’ 1992 Referendum

In the strange world of the National Party, where “Communism” equated with ‘Liberalism” – the Nationalists made a fatal error. Feeling confident that their hated nemesis ‘Communism’ no longer really posed a threat to their idea of the ‘Western World’ democracy when the Berlin Wall collapsed in 1989 with the resultant beak up of the Soviet Union. Feeling more confident that with the loss of its ‘communist’ backers the ANC plans as to a socialist communist take-over of South Africa would now not be possible and they would be in a position to ‘talk’. The National Party was on the ascendancy in terms of ‘seats’ in Parliament in 1989 using more gerrymandering and with the SADF enjoying 5% GDP spend (the average spend of a NATO country on the military is 2% GDP) they were now more powerful than ever – they now even felt confident that with a negotiated settlement with the ANC they had a shot at a sustained political future for themselves. They had started Apartheid, but now they would rather magnanimously end it and all would be forgiven.

So when they hit internal political hiccups and resistance from within their party, coupled with resistance from the ‘all white’ Conservative Party and Afrikaner extreme right (AWB) – and with the ANC not really rolling over in the negotiations. They made the fatal error of thinking they needed ‘populist’ support and put forward what was to become the last ‘whites only’ vote on the issue of Apartheid. But instead of a party political vote where they had a constitutional seat advantage which would see them over the line, FW de Klerk instead opted for a ‘one to one’ count, a ‘one man one vote’ all white referendum. For the first time since 1948 it would become clear again who in the white community supported Apartheid and who didn’t, and this time constitutional boundaries were moot.

The Nationalists for the first time sided with the ‘liberal white ‘left, it backed the support to end Apartheid and joined forces with the ‘Democratic Party’ (the last remaining “Liberal” party – the direct result of the Progressive Party and the merging of the now collapsed Union Party, Labour Party, Liberal Party and Union Federal Party, Reform Party and all their Torch Commando forebears) – it would spell out just how many liberty loving white South Africans there were to vote ‘Yes’ to end Apartheid – the nearly 3 million strong white voter base brought back an astonishing result. 69% of whites wanted the end of Apartheid – nearly 2,000,000 whites (read that again – 2 million whites willingly and very peacefully voted to end what is now incorrectly touted as their ‘Apartheid privileges’).

In terms of demographics this was not really too dissimilar to the split faced by Jan Smuts in 1948 – the populist white vote was still very much an anti-apartheid vote, even 40 years on. The only difference between 1948 and 1992 was the fact the white electorate base had grown to three times that of 1948 and an armed and civil struggle had kicked off in the interim. The very percentage of the white voter block that the Torch Commando had worked so hard to reinvigorate in its protests from 1951-1953 were still largely intact and had just grown exponentially over the years.

The truth of the matter is that an armed struggle did not really end Apartheid, the ballot did. The initial objects of The Torch Commando as outlined by Sailor Malan and Louis Kane-Berman, that the ‘ballot’ was the only viable way to oust Apartheid, held as true in 1992 as it did in 1951. There was no MK led ‘military victory parade’ over defeated SADF/SAP forces – and that’s because there was no military victory. Victory in the end was a moral one, and it was one in which democracy loving white South African’s played a key role – the first-time white people were given proper representation and voice by weight of sheer numbers – and they voted Apartheid out – that is a fact.

The ‘Yes’ vote spelled the end of the National Party, it had fundamentally misinterpreted its support. Its voting base was fractured further after the 1994 Democratic elections and it continued to diminish until one day it did an unbelievable thing – after flirting with old ‘white’ enemy, the Liberals and Democrats now in a Democratic alliance (DA), the National Party then closed shop, left the Democrats and walk the floor in April 2005 and joined the ranks of none other than the African National Congress (ANC) – their much hated ‘Communists’. So much for Afrikaner Nationalism and the visions of Malan and Verwoerd – because the inconvenient truth is that this is what they are left with as a legacy.

In Conclusion

In the light of ‘Revolutionary History’ which has now become so predominant in the current ANC government and in formal education, incorrectly shaping the Struggle as a ‘race’ war and not an ideological and ‘moral’ one – our task to the ‘truth’ becomes more important than ever.

From a military history perspective, the white armed struggle has not been given its full scope, the dots have not been fully connected and the ‘golden threads’ not completely woven. Much of ‘the white struggle against apartheid’ it is either ‘lost’ or inadequately woven into the modern narrative of the struggle for the sake of political rhetoric favouring revolutionary Black consciousness and reform.

The ‘Truth’ – if we seeking it, is that here is a rich and very deep history of both ‘white’ military and ‘white’ political struggle against Apartheid, the epicentre of which is a little known and little regarded movement called The Torch Commando – and why is that so important?

Because future stalwarts of ‘The Struggle’ cut their political teeth in the Torch Commando – its members provide the military experience, structure and training for all the ‘Liberation’ non-statute forces – from the African National Congress’ MK to the Liberal Party’s ARM. Where they do not provide a direct military link to the armed struggle, Torch-men also become guiding lights in the political struggle – from Smuts’ old United Party and the Labour Party to the evolved Progressive Party, Union Federal Party and Liberal Party (the origins of today’s Democratic Alliance) which all spin out of The Torch Commando.

In fact, its Torch Commando members who are at the epicentre of the paradigm shift in opposition white politics after 1948 and again in 1961 and finally again in 1994. It all comes full circle, when three key old surviving Torch Commando stalwarts are at the very core of South Africa’s transition to full democracy – one lawyer, one Communist and one Democrat.

Michael Corbett joined the Army in 1942 to fight in World War 2, leaving as a Lieutenant, after the war he was an aspiring lawyer and he joins The Torch Commando in protest against Apartheid becoming part of the Torch’s legal team. Years later and a long distinguished career, by 1989 he is appointed South Africa’s Chief Justice. As Chief Justice he delivers the opening speech at the inaugural session of CODESA in December 1991 – marking the beginning of the negotiations for a new constitutional order for all South Africans.

During the CODESA negotiations, the critical team was ‘Working Group 2’ dealing with Constitutional Principles, in it are the respective party’s ‘Big Gun’ negotiators … Gerrit Viljoen, Cyril Ramaphosa, Colin Eglin, Joe Slovo and Ben Ngubane.

Yup, two old Torch Commando stalwarts are sitting opposite one another bashing out South Africa’s Constitution paving the way to the vote – Eglin and Slovo. This group is also notorious during the negotiations for hitting impasses and creating crisis after crisis as negotiations falter and hang on the edge of the proverbial cliff.

Peter Soal, the late PFP leader would say of these impasses that it was;

“Colin Eglin’s negotiating prowess that was recognised by Joe Slovo in particular and, when an impasse was reached, the two would get together and generally find a compromise and way forward that enabled talks to continue and, eventually, a worthy constitution to emerge.”

Colin Eglin would say of Joe Slovo;

“Particularly close to my political and private soul was Joe Slovo, most remarkable of them all. Charming and intelligent, he was a creative lateral thinker with a deep human understanding”.

Eglin and Slovo shared a deep common bond, not only were they both veterans of the second World War and ‘brothers in arms’ with a mutual respect that only soldiers find in one other, they are also political veterans of The Torch Commando and they both chartered a course of political struggle with the same aim in mind – albeit on different trajectories.

As a critical part of the Multi-Party Negotiating Forum (MPNF), Eglin and Slovo hammer out the Interim South African Constitution – the basis of the South African Constitution as we know it today, by no means perfect but one of the most liberal and enlightened constitutions in the world. In a way, it’s the Second World War that forges these ideals of liberty in the South Africans taking part it, it’s a constitutional crisis after the war which triggers them into mass anti-apartheid protests as The Torch Commando in 1951 and in the end after an armed and political struggle, they emerge to change the constitution of South Africa completely and build it into the ‘Torch’ of liberty we see today.

To top it all, entering the stage again, is Justice Michael Corbett, our third Torch-man who wraps it all up for The Torch when he inaugurates Nelson Mandela as the new State President of a fully democratic South Africa on the 10th May 1994.

That’s why understanding The Torch Commando and bringing its history forward and preserving it properly is critical to our shared understanding of struggle against Apartheid.

Editors Note:

Small teaser for those who wish to really know more on the Torch. There is a definitive book on the Torch Commando which is been planned and penned by Peter Dickens in collaboration with leading academics like Graeme Plint and in support of the legacy of Louis Kane-Berman and Sailor Malan and their families, do look out for it when it hopefully makes it to a publisher.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References

Liberal Opinion – March 1962 ‘Jock Isacowitz’ by Peter Brown

A flying Springbok of wartime British skies: A.G. ‘Sailor’ Malan. By Bill Nasson – University of Stellenbosch

South African History On-Line (website)

Liberals against Apartheid – A History of the Liberal Party of South Africa, 1953–68 by Randolph Vigne

The United Party and the 1953 General Election, University of Durban-Westville by W.B. White

‘Contact’ the Liberal Party’s Newsletter 1954

The Alan Paton Centre and Struggle Archives at the University of KwaZulu-Natal on-line – Interviews with Peter Brown and the History of the Liberal Party South Africa

Business Day press-reader, Nov 2018

Values, Duty, Sacrifice in Apartheid South Africa. By Peter Hain

Crossing the boundaries of power: the memoirs of Colin Eglin.

The Rise of the South African Reich by Brian Bunting 1964

Not for Ourselves – the history of The South African Legion – South African Legion of Military Veterans

The Springbok and the Skunk: War Veterans and the Politics of Whiteness in South Africa During the 1940s and 1950s by Neil Roos – University of Pretoria

A tribute to Colin Eglin – By Peter Soal – 02 December 2013.

The Torch Commando & The Politics of White Opposition. South Africa 1951-1953, a Seminar Paper submission to Wits University – 1976 by Michael Fridjhon.

The South African Parliamentary Opposition 1948 – 1953, a Doctorate submission to Natal University – 1989 by William Barry White.

The influence of Second World War military service on prominent White South African veterans in opposition politics 1939 – 1961. A Masters submission to Stellenbosch University – 2021 by Graeme Wesley Plint

The Rise and Fall of The Torch Commando – Politicsweb 2018 by John Kane-Berman. Large extracts taken from the late John Kane-Berman memoirs of his father Louis Kane-Berman with the kind permission of the Kane-Berman family.

Raising Kane – The Story of the Kane-Bermans by John Kane-Berman, Private Circulation, May 2018

The White Armed Struggle against Apartheid – a Seminar Paper submission to The South African Military History Society – 10th Oct 2019 by Peter Dickens

Sailor Malan – By Oliver Walker 1953.

Lazerson, Whites in the Struggle Against Apartheid.

The White Tribe of Africa: 1981: By David Harrison

Ordinary Springboks: White Servicemen and Social Justice in South Africa, 1939-1961. By Neil Roos.

Related Work

The White Struggle Against Apartheid: The ‘White’ armed struggle against Apartheid

The Torch Commando Series

The Smoking Gun of the White Struggle against Apartheid!

The Observation Post published 5 articles on the The Torch Commando outlining the history of the movement, this was done ahead of the 60th anniversary of the death of Sailor Malan and Yvonne Malan’ commemorative lecture on him “I fear no man”. To easily access all the key links and the respective content here they are in sequence.

In part 1, we outlined the Nazification of the Afrikaner right prior to and during World War 2 and their ascent to power in a shock election win in 1948 as the Afrikaner National Party – creating the groundswell of indignation and protest from the returning war veterans, whose entire raison d’etre for going to war was to get rid of Nazism.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The Nazification of the Afrikaner Right