Torch Commando Series – Part 4

The Torch – a mixed bag

On the back of the successful widespread support of ‘The Steel Commando’ and determined to continue the fight to effect regime change, the ‘The Torch Commando’ took shape and it took to a more formalized structure of a central command with devolved authorities in the various regions of South Africa, using military discipline, military styled planning and lines of communication to activate.

Officially launching as the Torch Commando, Group Captain Sailor Malan, the hero of The Battle of Britain was elected National President of the Torch, Major Louis Kane-Berman, a highly respected North Africa and Italy campaign officer, was elected National Chairman. To keep a very even keel, the appointed Patron-in-Chief for the Torch Commando was Nicolaas Jacobus de Wet, the former Chief Justice of South Africa. The National Director was Major Ralph Parrott, a ‘hero’ of the Battle of Tobruk from the Transvaal Scottish who received the Military Cross for bravery.

The Torch went to pains to put two English speakers and two Afrikaans speakers at the top of the organisation to reflect balance – critical where white Afrikaners, who made up 60% of the 334,000 South Africans who had volunteered to fight in the war against Nazim. Some, disillusioned with the military’s demobilization and re-integration process and been ‘politically disenfranchised’ had voted for the National Party in 1948 in protest and expecting change to their circumstances, and the Torch sought to ‘bring them back’ to centre-line politics on the ‘camaraderie’ ticket (however, this group was small and fleeting, in the main a ‘Service block’ vote emerged in the United Party’s ambit and it did not really materialize in the National Party’s ambit).

The manifesto of the Torch Commando was released, it was a ‘rededication of service and a call to the nation,’ it read:

We, veterans of many wars, once more dedicate ourselves to our land. In the belief and with the guidance of Almighty God, we shall pursue the truth and uphold it.

We shall strive for justice, mutual trust and honour in all our affairs.

South Africans, men have died that you shall be free, let no-one rob you of your heritage.

Having met together in a spirit of mutual faith and trust, our father’s founded the Union of South Africa. In the same spirit let us go forth together, free men, free from fear, free to worship and free to speak.

South Africa Awake.

Rise of The Torch

All over the country people started to flock into devolved Torch Commando structures and almost immediately ‘joined up’. Hundreds at a time joined new branches springing up outside the major metropole branches/commands in small places like Pinetown, Paarl, Umtata, Amanzimtoti, Eshowe, Dundee, Colenso, Eliot, Strand, Fish Hoek, Sunday’s River Valley, Bedford and Ficksburg. By the end of September 1951 there was a branch in every Reef town and on most of the mines.

The enthusiasm for ‘The Torch’ (as it became to be known) was almost sporadic and widespread, as if an immediate need of the returned war veterans to express frustration at the National Party’s policy of Apartheid and re-kindle their camaraderie had been answered in a legitimate political pressure group. Such was the support that it took Louis Kane-Berman and Sailor Malan by surprise.

Within three months of the official launch of the Torch, it had almost 100 000 members enrolled in 206 branches. By the end of January 1952, there were 120 000 members in 350 branches. By mid 1952 the Torch had 250 000 members.

Membership of The Torch was not exclusive to military service, it was open to all who supported the Torch’s cause. A significant non-veteran joining The Torch was Alan Paton (the famous author and future leader of the Liberal Party). Of its zenith membership of 250,000 members one quarter were white ex-servicemen – about 63,000. Membership was relatively cheap and accessible – half a crown (about R 100 or £ 5 today’s money), and ‘Torch’ lapel pins and various other ‘Torch’ symbology was adopted by members to signify to others their political convictions and support of ‘The Torch’ and its ideals by way of a ‘badge’ (lapel pin).

Of major concern to the National Party was the profile of people joining The Torch Commando, members soon included five former Judges, and ten Generals, including the Lieutenant-General George Brink CB, CBE, DSO, who had a very distinguished military career, he was the Commander of the 1st South African Division during the Second World War. In 1942, Brink turned over command of the division to Dan Pienaar and Commanded the Inland Area Command in South Africa from 1942 to 1944. Other Generals joining the Torch were the highly regarded Major General R.C. Wilson and Brigadier A.H. Coy.

Another very notable General joining The Torch Commando was General Kenneth van der Spuy CBE MC, the man who pioneered the formation of South African Air Force (SAAF) under General Smuts’ directives. General Van der Spuy is regarded as the modern father and founder of the SAAF (Smuts would be the ‘Grandfather). After the war he was a key role-player in the establishment of The Springbok Legion and on the executive of the South African Legion of Military Veterans (The South African Legion), South Africa’s prima and largest veterans’ association with 52,000 registered veterans.

Alarmed by this rapid rise in protesting whites and the profile of members joining The Torch, the National Party did what it did best, and acted ‘decisively’. It looked to the most important ‘feeder’ for the Torch Commando, the military – the Union Defence Force, and immediately instituted a ban on all permanent force members still serving as well as any public servant from joining the Torch, amending The Public Service Act.

However, they had difficulty instituting this ban on the Citizen Force units and Regiments – whose members continued to join. The ban in many ways did affect membership as many still in the active employment of the government – either in the military or in the systems like the judiciary were discouraged from joining The Torch, lest they lose their livelihood.

El Alamein Commemoration Campaign – October 1951

The Torch Commando targeted the anniversary celebrations of the Battle of El Alamein pivoting around the 26th October 1951 to draw countrywide protest and support. In all the El Alamein Commemoration Campaign drew a staggering 150,000 people into active protest against the National Party government. A coordinated protest this size had never been seen in South Africa before.

Ten Days before a mega-rally planned for Johannesburg, Sailor Malan lit a flaming torch outside the Langham Hotel in Johannesburg, the Torch was placed on a ‘Torch Truck’ which then travelled around the country driving up awareness and support and creating media hype (in all it travelled over 6,500 km drumming up support). A huge crowd greeted the Torch Truck when it finally arrived in Johannesburg just in time for the El Alamein commemoration protest. The Johannesburg torch protest started when veterans carrying flaming Torches gathered at the square next to the City Hall, converging on them four separate mustering points elsewhere in the city came thousands of ex-servicemen and women, twelve abreast, singing the old stirring war songs of their day.

A massive crowd, tens of thousands, gathered around a dais erected among the palm trees on the square to hear speeches from Sailor Malan and Kane-Berman, who told them that the flaming torches were symbolic of the searchlights used at Alamein to guide troops to their objectives and remove the possibility of any man being lost. He said;

“These are the lights of democracy – let them be a source of comfort to the people of this country whatever their language, race, or colour. They convey a message to the people of South Africa in the name of those who fought and lived and in the name of those who fought and died.”

As to the large protests like this one, according to the Star Newspaper on 27th October 1951, the Torch Rallies for EL Alamein Commemoration brought the following numbers, Johannesburg 40,000 protestors, in Cape Town 20,000, in Durban 10,000 and in Pretoria 6,000. But the protests did not stop at these large events, large bonfires symbolising Torches were lit across the country, some of them on the mountains above Barberton, six in Pretoria, and one at a peak high in the Drakensberg. People gathered also in Benoni, Krugersdorp, Vereeniging, Port Shepstone, Empangeni, and elsewhere. Hundreds of bonfires were lit around Kimberley in a massive ‘fire chain’. These smaller protests were often linked to a bugler playing the Last Post followed by a period of silence for the fallen.

In all, it is estimated that a staggering 150,000 people would ultimately participate in the Torch’s El Alamein Commemoration protests. The government sat up and noticed, the Torch posed a potential military threat. Dr D.F. Malan, South Africa’s Prime Minister announced:

“People content that the Torch will go a little way and then vanish. That is not my view. The Torch Commando is to be taken seriously because it had a military or semi-military character. Private Armies of that nature cannot be tolerated …“

Officially, the government tried to gag the entire protest by way of instructing the SABC not to broadcast on any of the dates or activities, an instruction the broadcaster followed. The Torch tried to initiate the same campaign the following year in October 1952, but their permissions for gatherings were ‘banned’ – declined by Ben Schoeman (an NP Cabinet Minister).

After the El Alamein activations five guiding principles were penned crystallising the objectives of the movement by way of principals:

- To uphold the spirit and solemn compacts entered into at Union as moral obligations of trust and honour binding upon the people

- To secure the repeal of any legislation enacted in violation of such obligations

- To protect the freedom of the individual in worship, language, and speech, and to ensure his right of free access to the courts

- To eliminate all forms of totalitarianism, whether communist or fascist

- To promote racial harmony in the Union

Rejection of Communism

Noteworthy at this point is the Torch Commando in their objectives rejects Communism – they do this primarily because the National Party’s anti-communist legislation is so open ended. It is the legislative tool the National Party would use the Communist Party of South Africa and the Springbok Legion, it would also fundamentally undermine the activities of Torch Commando, and would even be used to curtail, arrest and even gag mainstream politicians in the Liberal Party and the Labour Party.

This was the infamous ‘The Suppression of Communism Act 44 July 1950’. The act was a sweeping act and not really targeted to Communists per se, it was intended for anyone in opposition to Apartheid regardless of political affiliation.

The Act defined communism as any scheme aimed at achieving change–whether economic, social, political, or industrial – “by the promotion of disturbance or disorder” or any act encouraging “feelings of hostility between the European and the non-European races … calculated to further (disorder)”

Thus, the Nationalist government could deem any person (liberal, humanitarian or Communist) to be a ‘communist ‘if it found that person’s aims to be aligned with these aims. After a nominal two-week appeal period, the person’s status as a communist became an un-reviewable matter of fact and subjected the person to being barred from public participation, restricted in movement or even imprisoned. In effect, it could be, and was applied to anyone from both the White community and Black community not buying into Apartheid.

Within the formation of the Torch Commando and paid-up members, were members of The Springbok Legion, and many of them had been members of the Communist Party of South Africa before and after the war. Influential and highly vocal Torchmen like Cecil Williams, Wolfie Kodesh, Jack Hodgson, Rusty Bernstein, Fred Carneson and Joe Slovo were all card carrying and outspoken members of the Communist Party.

Under the edicts of the Suppression of Communism Act 44 July 1950 the Nationalist government could have immediately such down The Torch Commando and arrested its members if it could prove it was a ‘Communist threat’ or carried with it Communist philosophy and ideology. This would force the communist members in the Torch to seek other more robust avenues to political protest like ‘The Congress of Democrats’ – some like Rusty Bernstein, Joe Slovo and Jack Hodgson are even arrested and charged with treason, alongside the likes of Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela in 1956.

This rejection of Communism not only kept The Torch Commando clear of repressive government legislation, it also opened the Torch Commando to the great many war veterans and their supporters who feared the advent of Bolshevism and Communism and other forms of socialism like National Socialism (Nazism). By rejecting Communism, The Torch would open itself up to far greater appeal and take a far safer trajectory than toeing the line of its communist members. This would cause a schism between the more robust ‘Springbok Legionnaires’ with Communist leanings would eventually even take aim at The Torch Commando and issue much critique of The Torch in the ex-servicemen’s newspapers like ‘Advance’ whose contributors included the wives of Jack Hodgson – Rica Hodgson and Joe Slovo’s wife – Ruth First, amongst others.

As irony and own goals go, even ‘Advance’ which evolved from ‘The Guardian’ and ‘the Clarion’ from November 1952 to October 1954, becoming the “New Age” in 1962 was eventually banned and closed by the National Party. Such is the nature of ‘white’ politics in South Africa, it’s never held a unitary view.

Smear Campaign

Also the National Party government, being extremely concerned about the influence this movement might have, especially under the leadership of the war hero, acted ‘decisively’ (as was its usual modus operandi) and went about discrediting the Torch Commando and its leaders through means of negative propaganda.

For the rest of his life, Sailor would be completely ridiculed by the Nationalist government. The National Party press caricatured him ‘a flying poodle’, dressed in his leathers and flying goggles, in the service of Jan Smuts and the Jewish mine-bosses, who they referred to as the “Hochenheimers”. The National Party openly branded Sailor Malan as an Afrikaner of a ‘different’ and ‘unpatriotic’ kind, a traitor to his country and ‘Volk’ (people).

The ‘Crisis’ Continues – 1952

Dr D.F. Malan also publicly warned Torch Commando members, that as he viewed them as being paramilitary in nature, Torch Commando members who picketed National Party rallies would be met with a violent response, and this would set a nasty tone at grass-root levels.

In the National Party heartland town – Lydenberg, the new year started badly on 11th Jan 1952, emboldened by the governments position on the Torch Commando, a Torch meeting in Lydenberg was violently broken up by Nationalists (in the clash, Charles Bekker, the Torch’s National Organiser’s arm was broken).

The Torch announced that they would be back before the end of January in a show of strength and force. Commandant Dolf de la Rey, the old Boer War, ZAR veteran headed up the steel commando styed convoy again as hundreds of vehicles descended on Lydenberg. This time the Nationalists thought better of violence and there was no trouble, to drive the point home as to the freedom to assemble and protest a new Torch Commando branch was promptly constituted in Lydenberg.

Video: AP footage of the Torch Commando in action, note the military styled operations room the use of leaflet drops from the air, also note the marketing materials the ‘V’ for Victory slogan which was a wartime rally call.

Whilst the Torch was focussed on small town grass-root recruitment and expanding demonstrations and branches, things started to go their way as to the ‘Constitutional Crisis’ – in a landmark decision in March 1952, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court declared the Separate Representation of Voters Act as

“invalid, null, and void and of no legal force and effect.”

The Torch Commando’s jubilation at the ‘win’ did not last long. Dr D.F Malan declared that courts were not entitled to pass judgement on the will of Parliament. Kane-Berman would warn that

“the fecundity of a mind like that of Dr Dönges cannot be ignored”. He and his colleagues in the Broederbond would find a way “of circumventing this judgement”.

And that is exactly what happened next.

The Nationalists acting very un-constitutionally and with unparalleled cynicism over time, would pass the High Court of Parliament Act, effectively removing the autonomy of the Judiciary in matters regarding the Constitution and loaded the Appellate Court with additional NP sympathetic representatives.

So, the ’Constitutional Crisis’ continued. Sailor Malan was quick to react, of the Nationalists by-passing of the highest court in the land he said:

“The mask of respectability is there for all but the blind to see. The sheepskin has fallen off and the fascist wolf is snarling at the courts. We accuse the government of preferring jungle law to the rule of law. We accuse them of preferring unfettered dictatorship to a constitution which binds them to certain standards of procedure.”

In a co-ordinated and with military precision, Mass Torch protests in major metropoles immediately convened in Umtata – 3,500 people. Pietermaritzburg – 15,000 people, Johannesburg – 20,000 people. In Pretoria 20,000 people gathered despite being teargassed. The Torch leader in Pretoria, John Wilson, said;

“Dr Malan was putting himself above the courts in the best tradition of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini”.

Torch Light protest meetings also immediately sprang up in minor metropoles – many in National Party heartland towns – from Groblersdal to Louis Trichardt, further attesting to the gradual conversion of Afrikaner voters and the pulling power of The Torch.

As to the Constitutional Crisis, regardless of the Torch’s mass protest efforts, the Nationalists pressed ahead, they continued to load the Parliamentary system to get their majority by gerrymandering constituencies, they appointed National Party MP’s as ‘Native Representatives’ in the Senate and illegally incorporated South West African (Namibian) MP’s into the Senate (South West Africa as an ex-German colony was a National Party sympathetic block, given their right wing German sympathies during the war, and although a ‘Protectorate’ was still a separate country).

Kane-Berman would say of it;

“a vast section of the people of South Africa are no longer prepared to stomach the totalitarian tendencies of the present government with its piecemeal invasion of their civil liberties and its tinkering with the Constitution.”

Simply put, if the rights of the coloured people could be removed then nobody’s rights were safe. More action was needed, simple protesting by Torchlight was not working, real and meaningful change needed to occur for the Torch to remain relevant. A coalition of all opposition parties who had members who could vote needed to come together in a concerted effort using all forms of politicking to oust the Nationalists constitutionally – by the ballot box.

This would take shape in an organisation called ‘The United Democratic Front’.

The United Democratic Front

The Torch’s mixed bag of moderate ‘pro-democracy’ and firebrand ‘Liberal’ and ‘Communist’ members would also ultimately swing it from an independent ex-serviceman’s popular movement to a political alliance with stated affiliations.

However, the Torch gradually came to realise that mass protesting would not lead to effective regime change and ‘door to door’ politicking would be required to build ground-swell voter’s block and beat the National Party at the next General election.

Sailor Malan would nail the Torch’s colour’s to the United Party’s mast and say of this move to becoming more of political movement rather than a popular protest movement.

“We have no intention of affiliating with the United Party, but since the National Party was elected to power in a constitutional way, we must fight them constitutionally, and we can only do this by helping the United Party.” (the largest and most viable opposition party).

However, the ‘mixed bag’ of vastly different political views of the Torch’s members would not enable it to rally behind any single political party, Sailor Malan would also say that it would be fatal for the Torch to form a separate party in its own right – so a better vehicle was to needed to enable the Torch to politic at grass-roots across the political spectrum.

This came in the form of the United Democratic Front (the ‘first’ UDF – the UDF of later years was an entirely different body with the same name) – announced by Koos Strauss on 16th April 1952, the leader of the United Party (UP) as essentially an alliance between the Torch and the UP. The full-makeup of the United Front would be partnership between the Labour Party (LP), the Torch Commando, an organization called ‘The Defenders of the Constitution’ and the United Party (UP). In essence The Torch would remain independent, but it was now free to canvass votes for the UP and the LP in the upcoming 1953 General Election.

To many, the joining of the UDF and opening the Torch to the party politics of the UP and the LP would signal the point where the Torch would ‘jump tracks’ from its singular grass-roots vision of demanding the removal and/or resignation of the National Party as a political pressure group and become a vehicle on which the UP especially could rely on for its party-political aims, its messaging becoming defused as it entered mainstream politics. This would be the first signal of the end of the Torch.

A veiled threat

One area where this political dilution of the Torch occurred in mid April 1952. As an ‘ex-military’ movement it could realistically threaten the government with force, and this made the government very jittery and careful in the way it dealt with the Torch. At a Torch meeting in Greenside, Kane-Berman proposed a ‘National Day of Protest’ and said;

“We will fight constitutionally as long as we are permitted to fight constitutionally, but if this government are foolish enough to attempt unconstitutional action, then I say the Torch Commando will consider very seriously its next step.”

In his mind the next step would be a national strike and countrywide shutdown, however he also went to give a veiled military threat and said:

“As good soldiers we must have something in reserve!”

The National Party took this statement literally to be a final threat of military force and the idea of National Strike or ‘National Shutdown’ by ‘whites’ would embolden the ‘blacks’ to join in a national revolt – in their eyes a powder-keg. The Afrikaans media jumped on it declaring the Torch as provoking national chaos and drawing ‘blacks’ into ‘white’ politics. C.R. Swart, the NP Minister of Justice falsely declared that the government had evidence that The Torch was plotting an armed uprising. Then Die Transvaler, falsely reported that the Torch had plans for a coup d’état.

Laughable as this all was Kane-Berman responded:

“I do not doubt that there is a plot afoot, but it is not the one mentioned in the Transvaler report. The real plot is a Nationalist one and it consists of trumping up an excuse to do precisely what Hitler did in Germany – ban opposition movements.”

Foreign newspapers now started picking up on the Afrikaner newspaper news-feed that the Torch was planning a coup d’état. National Party Ministers were so spooked many of them started surrounding themselves with bodyguards – by June, 250 new plainclothes policemen had been appointed to protect National Party Ministers. The whole issue, now blown completely out of proportion was demonstrable of just how fearful of the Torch the National Party had become.

The newly formed United Democratic Front had to jump in to diffuse the situation on behalf of their now aligned Torch Commando. Koos Strauss, the UP leader almost immediately re-iterated that the United Front (the UP and the Torch) intended to fight the battle constitutionally, there would be no national shutdown and there would be no threat of arms. In this way the UP ‘blunted’ the fighting edge and military threat of The Torch and forced its leaders like Kane-Berman to toe the UP’s party-political line and agenda.

D-Day commemorations – June 1952

On 6th June 1952, a Torch Commando procession was planned around D-Day anniversary – the invasion of Europe which would see the end of Nazi Germany – a mere 8 years into its celebrations.

A staggering 45,000 people gathered in Durban for a “hands-off-our-constitution” Torch Commando meeting. The meeting was preceded by a pipe band and march into the city of 5,000 Torch members.

In addition, 2,500 women met in the Durban city hall to dedicate themselves to unseating the Nationalist the government, so impressed by the convictions of the women, and aging Ouma Smuts, Jan Smuts’ widow and darling of ex-servicemen and women even sent them a goodwill message.

Wakkerstroom by-election – June 1952

Also, in June 1952 the National Party incumbent for Wakkerstroom died, forcing a by-election. Wakkerstroom was Jan Smuts old seat when he was ousted in 1924 and had become a National Party strong-hold. It became important because the UP wanted to show it had not lost touch with the rural vote and to the NP it became important as the African National Congress (ANC) had announced it’s ‘Defiance Campaign’ at the same time as the by-election and the NP wanted to show it still held the confidence and will of the voting people (albeit they were only white).

Although the seat was a ‘sure win’ for the Nationalists in any event, the Torch decided that a show of unity would be necessary to assert their freedom to assemble and meet anywhere they choose. The Torch also felt it would be an ideal opportunity to present a friendly face to the rural Afrikaners as militarily non-threatening – a moral opportunity to present themselves as ordinary decent citizens, contrary to the lies that were being told about them in the Afrikaans media. They proposed to set up a nearby ‘camp’ – have a meeting and then have a social gathering and ‘braai’ with the local farmers.

To protect their stronghold and assure themselves of the win the Nationalists announced that the United Front (the Torch in effect) would not be allowed to hold a meeting in the Wakkerstroom constituency. Local officials refused permission for the Torch to road transport equipment to the town – so the Torch charted a Dakota aircraft to fly in with all the necessary. The Police were then ordered to block any Torch Commando convoy, so the convoy simply drove around them on the open veld and entered Wakkerstroom to set up camp.

They held their meeting with no problems from the locals, asserted their right to meet anywhere and then had a braai with the locals who brought meat and vegetables with them, a nice friendly social.

By did all this goodwill and positive spin swing a vote? Nope, the United Party was soundly beaten at the poll, embarrassingly they had lost ground to the previous vote – on aggregate they had lost more voters to the National Party, in retaining the seat, the NP received 4.9% more votes than it had attracted in the 1948 election. This was taken as a barometer of the general state of the United Party’s appeal to the rural Afrikaner vote.

Summing up the reasons for the magnitude of the defeat, a United Party memorandum stated:

“the National Party candidates and election agents ascribe their success to the existence of the Torch Commando, the Kane-Berman ‘Day of Protest’ statement and the obvious tie up to the non-European protest movement. They were able to lump us (the UP) into a ‘bonte opposisie’ the Torch Commando, the Labour Party, Kahn, Sachs, Carneson (and) the African National Congress.”

By Carneson, they referenced Fred Carneson, a military veteran, leader of the Springbok Legion and a devout Communist. Based on this, the UP executive concluded at a meeting on the 17th July 1952, that in order to re-gain the confidence of their lost rural Afrikaner voters they had little choice but to move the United Party’s platform even closer to that of the National Party.

This would mean tapering back on the UP’s ‘liberal’ faction and their demand for a universal franchise for both black and white voters and a move towards the UP’s conservative faction who were happy the Cape Franchise for Colourds and who wanted to see an ‘eventual’ qualified franchise for black South Africans. This would spell, not only the death of the United Front, but the Torch Commando and the eventual death of the United Party itself.

On the up, in 1952, the Torch Commando continued to rise at the grass-roots level. Torch meetings attracted 3 000 in Witbank, 500 in Vryheid, 300 in Bathurst, 60 farmers in Salem, 400 at Montagu, 2,000 at Adelaide, 2 000 at Bredasdorp, and thousands again in the main metropoles of Pretoria, Johannesburg, Durban and Cape Town. Torch branches were formed in Oranjemund and Port St Johns. As to rising popularity Danie Craven, the South Africa Springbok rugby stalwart even joined the Torch.

However, in line with the fear that ‘The Torch’ was planning a military overthrow and National Party hype surrounding this, along with down-right under-handed politics – on the downside Torch rallies and meetings in the latter part of 1952 increasingly came under attack by Afrikaner Nationalists, so much so ‘Torchmen’ started to wear their ‘old tin hat’ brodie steel helmets to meetings. A Torch meeting in Queenstown was violently broken up, in Brakpan Nationalists lined the streets and spat at a passing Torch rally. A Torch/United Front meeting in Vrededorp was so violently attacked by Nationalists banishing iron bars and nailed sticks that 100 people had to be treated by doctors on site whilst others were taken to hospital. A Torch meeting at Milner Park was attacked and stoned.

The Torch and Race

One aspect of the Torch Commando that comes under scrutiny of modern ANC political commentators is the ‘whiteness’ of the organization. They are quick to dismiss it as an irrelevant movement because it was not inclusive of ‘blacks’ … but that would be to completely mis-understand what the Torch was. So, what’s with the ‘whiteness’?

The Torch had been formed to oppose the violation of the Constitution. Although the violations directly affected the voting rights of coloured people, this violation intended to create a “whites-only” vote – so it was a ‘Constitutional’ fight at the ballot to prevent the on-set of Apartheid in its more sinister forms. Only whites and Coloureds had the franchise, so only they could fight a constitutional fight at the polls and in the greater scheme of ‘white parliamentary constituencies’ the handful of parliamentary constituencies where coloured people were registered on the common voters roll was relatively small – however to this effect The Torch did have a few coloured branches in these constituencies – in the but it remained an almost entirely white organization.

Outside of The Cape, the vast majority in the rest of country of ‘Black’ people did not have ‘the ballot’ so they could not participate at all. Kane-Berman summed it up in October 1952 when he said that because the Torch’s fight was through the ballot box, there was no point in enrolling people who could not vote.

Since the Torch did not want to become a political party, the best way of throwing out the NP government in 1953 was to encourage Torch supporters to vote for its two parliamentary partners in the United Front, the United Party and the Labour Party. By late 1953 this had become the key objective of The Torch Commando, and it only really involved ‘whites’ and their ballot.

To illustrate the point, even the Coloured Servicemen felt the Torch was the ‘white man’s fight’ and not theirs. In July 1952, a letter to Sailor Malan the Kimberley Coloured War Veterans’ Association said;

“No good purpose will be served by us becoming members of your vast organisation, notwithstanding the fact that the Torch came into being on one of the most vital issues affecting the coloured people”. Our “sincerest wishes that (the Torch) shall grow in strength to face the crisis affecting South Africa …. Coloured people made great sacrifices and paid dearly for their loyalty in assisting to uphold democracy”.

Later in 1952 a group of coloured ex-servicemen declared that they had no desire to become members of the Torch’s fight as;

“(This) constitutional fight is the white man’s fight to re-establish the integrity of his word”.

The Torch’s mixed bag broad church of Communists, Liberals, Moderates and Democrats found common cause and ‘unity’ in their horror at the NP’s plans to violate the Constitution, but in reality true ‘unity’ did not go very much further than that. Any attempt to develop hard-line, defined and detailed policies on race in a country so racially obsessed with vastly different views on it might have split the organisation, so the Torch leadership chose to avoided it as much as possible and focus on what ‘unified’. In any event, the priority was to defeat the NP party in the general election due to be held in March 1953 and they would just focus on that.

Dr. Maurice McGregor is a regular member of the Torch, but very active and he gives a perspective on the issue as to race and The Torch and its mission, he said;

“I was in the Torch Commando for about two years and took part in several marches. As I remember it the commando was primarily created to protect democracy, meaning the democratic process, the right to hold political meetings, and this in effect meant protecting the United Party which was the principal opposition to a Nationalist party.”

He goes on to say on the issue of protesting against ‘Apartheid’ his position is one of a typical white United Party voter in the 1940’s and 1950’s many of whom maintained that it was important that Black South Africans be taken out of poverty first, the poverty cycle and lack of education needed to be addressed before any form of franchise is afforded to them. Maurice recalls:

“To say that they held mass protests against apartheid is correct so long as you don’t start defining too precisely what apartheid was about. For example, the torch commando would never have endorsed a vote for Africans, even a very limited vote for those with education and property. But they did oppose the specific steps involved in the application of apartheid such as the bulldozing of Sophia town and the creation of rural ghettos.”

On the racial make-up of The Torch Commando (that been an organisation for ‘white voters’ only) he points out that although predominantly ‘white’ it was not exclusively white, he says;

“(The Torch) was not only white. There were Blacks as well as coloureds in the Torch Commando. But then there were very few Blacks in the Army.”

The ANC’s Defiance Campaign and the Swart Bills

Black resistance to Apartheid was also starting to lean towards violent civilian defiance as the ANC’s Defiance Campaign, officially launched from 26th June 1952, started to descend into full blown rioting in every major metropole around the country by October 1952, this was also not a stated aim of the Torch Commando (Kane-Berman’s National Shutdown statement aside).

It was clear from the nature of the Defiance Campaign that the ANC and The Torch were on different political trajectories. However, the Torch did take a strong position when Kane-Berman in September 1952 and now re-elected as the Chairman of The Torch Commando called on the Nationalist government “to cease its suicidal policy of fanning the flame of race hatred and to meet the non-European leaders in conference.”

The ANC’s Defiance ironically would also trigger the demise of both The Torch and The UP and spit them apart, and it’s not what you think – it would come from the National Party in the form of new statutes and because of polarising views within the United Party to them. So how is that?

In response to ANC’s Defiance Campaign, the National Party behaved ‘typically’ in January 1953, C.R Swart introduced the “Whipping Bill” (giving powers to Police to give lashes to people inciting political violence) and the “Public Safety Bill” (to prevent highly defiant political gatherings in the interests of safety and call a ‘State of Emergency’ when needed).

Known as the ‘Swart Bills’ the Torch was bitterly opposed to these bills – and not without good reason, the ‘Swart Bills’, which gave the Minister of Justice immense powers in the event of civil unrest. Had these Bills been in place when the Steel Commando rioted in Cape Town in May 1951 the State would have had the powers to imprison and whip the Torch Commando’s executive. However, the United Party dithered over these Bills as the conservative element within the UP felt they were decisive in resolving spin off violence from the ANC’s Defiance Campaign and therefore necessary.

On the other side of the fence, the United Party would support the National Party in passing Swart Bills on the grounds of national security, concerned with the unrest the ANC’s Defiance Campaign was creating whereas the Torch insisted that the bills conflicted with their principles and were the re-curser to fascist dictatorship.

Louis Kane-Berman argued;

“… unless the Torch Commando take the lead and the initiative in rousing public feeling against these Bills, the lead will be taken by other less responsible organisations (both European and non-European)”

Kane-Berman also, after rioting broke out, stated that;

“we (in the Torch) are not surprised, nor should be the Nationalist leaders be, that extreme elements among the natives have gone berserk.”

The infamous “lunch“

The issue over the Swart Bills came to a head when Louis Kane-Berman attended a luncheon hosted by the Torch’s primary benefactor and UP stalwart – Harry Oppenheimer. Harry Oppenheimer pressed Kane-Berman to elaborate on the Torch’s position with regard The Swart Bills, and was highly offended, when a United Party Minister of Parliament with whom Kane-Berman had served alongside in the North African campaign during the war, rebutted Kane-Berman’s argument on the evils of the Bills and detention without trial when and he flippantly stated:

“Louis you are talking nonsense. During the war Smuts threw many Afrikaners into prison without trial and now because the government wants to imprison some …(African)… trouble-makers, you now wish to raise all manner of objections.”

Alarmed that the United Party (UP) would support the bills, Louis Kane-Berman summoned The Torch Commandos National and Provincial executives and members of provincial executives of the Torch to Cape Town for an emergency meeting, also attended by leaders of the UP and of the Labour Party (LP). The LP was bitterly opposed to the bills. The UP representative, Pilkington-Jordan failed to convince the meeting of the UP position in support of the Swart Bills, so to conclude the meeting the Torch executives “decided unanimously there and then that if these bills went ahead, we would now call a National Day of Protest”.

Louis Kane-Berman issued a press release reaffirming the Torch’s stance against the Swart Bills on the 8 February 1953 – the invited press gave it a standing ovation so well was it received, “to my surprise” said Kane-Berman later. The press release drew a line in the sand as to The Torch’s political intentions and it immediately put The Torch at loggerheads with the UP and with the likes of Harry Oppenheimer, the Torch’s primary financial benefactor and sponsor.

The Torch had reverted to their original threat of shutting down the country and aligning with the objects of the ANC’s defiance campaign, and almost immediately there was dissent over the call for a ‘National Day of Protest’ within the Torch at a grass-roots level from the Torch’s rank and file who supported the UP. Torch members declaring the ‘day of protest’ as not properly approved by the Torch’s structures – the organisation now fighting internally with its leadership started the slippery slope towards an implosion.

The General Election – April 1953

Although Louis Kane-Berman would describe these two bills and the loss of financial support from Oppenheimer and support from the UP as the death-knoll for the Torch, its broader than just that. The real death-knoll would come in the 1953 General Election. The NP went into the election campaigning taking advantage of the unclear UP policies on black emancipation and weak leadership, promoting the ‘red danger – communist – rooi gevaar’ threat of ‘the Torch’ and ‘Springbok Legion’ and the ‘black danger – swart gevaar’ of the ANC and its defiance campaign. The ‘fear factor’ resonated with white voters fearing an uncertain future and seeking strong leadership and structure.

Again, as in the 1948 election, the National Party did not win a majority vote – it won 45% of the vote, but more importantly it won more constitutional seats, increasing its number of seats from 86 before the election to 94 – bringing it 61% of the ‘Constituency’ vote – well up on its performance in 1948. The UP’s seats dropped from 64 to 57. Labour dropped from 6 to 5.

Ideological Conflict – Natal

The Torch Commando dithered between two conflicting Constitutional issues, the first surrounding the Cape Coloured Franchise – which in essence called for the maintenance of the South African Union on moral grounds and the second issue, Natal’s sovereignty – which called for a break-up of the South African Union on legal grounds. Diametrically opposing views indeed.

The ‘Apartheid-Lite’ politics of the UP to attract back the vital marginal ‘white’ voters drawn to the National Party in the 1948 election and the ‘Liberal’ UP Torch members at odds with their party’s politics would ultimately lead to downfall of the Torch (and eventually to the downfall of the UP itself).

To illustrate the effect of this political feud in which The Torch now found itself in, after the 1953 elections the leader group of the Natal Torch Commando who were in the United Party, split from the United Party to form their own ‘Union Federal Party.’ The Party stood for full enfranchisement of Indian and Coloured voters and a qualified franchise for Black voters. As much as Sailor Malan tried to assure all that their choice was not that of The Torch and the Torch had nothing to do with it or its stated aims, key members of the Torch resigned over the matter – including The Patron in Chief.

Critical to The Torch’s strategy was that it attempted to avoid been party political and simply be a ‘mixed bag’ of political views, with the idea of re-igniting the old war time camaraderie to swing the ‘service vote’ so as to oust the National Party at the ballot box through a united front of political opposition.

It made it clear that although a ‘militant’ movement it was not a ‘military’ one. It liked to hint at its potential to become a military threat but made it very clear that it was not an armed resistance movement or military wing of any political party, it also made it clear that it was not a ‘political party’ – it left its members to campaign and politic for any party in opposition to the National Party. This wishy-washy standpoint would lead some of its members into military resistance and others into political resistance and would count as one of the reasons for the movement’s ultimate downfall.

A heady combination of the 1953 UP Election loss, the firebrand anti-Apartheid Liberals and Communists in the Torch and the state’s legislature actions banning or politically restricting members of The Torch – would all result in the final nail in the Torch’s coffin.

Demise

In June 1953, the Torch met in Johannesburg for its second national congress and decided by a narrow majority to continue, but in reality – without meeting its first raison d’etre – the removal of the NP in 1953 General Elections – the Torch was done and it ceased to really exist.

As to the Torch’s second raison d’etre – the Removal of Coloureds from the Common Voters roll to stop the slide to more sinister Apartheid legislation and a Republic – after the 1953 elections the National Party was able to complete its strategy of loading the senate and by-passing the Judiciary and by 1956 the Colourds were removed from the voters roll. That opened the way forward for Apartheid proper and by 1960, the ‘Union’ Constitution would fall apart when a South African Republic was declared with a ‘whites only’ vote with the aid of ‘whites only’ voters in SWA (Namibia) to swing a tiny referendum majority (just 1%) to a National Party ‘Keep South Africa White’ referendum promise.

As to the United Democratic Front. After the 1953 elections, the UP’s demise was also set. It’s firebrand Torch Commando members in it would split the party and form the Liberal Party and the Progressive Party. The UP would attempt re-direct Koos Strauss’ conservative approach to include a more palatable ‘ex-services’ appeal by appointing the very popular ex-services choice – Sir De Villiers Graaf to lead it. But, it was done, the Progressive Party split, led by ‘Torchmen’ like Colin Eglin would eventually take over as official opposition and the UP would cease to exist. The Labour Party in turn would also lose relevance in the battery of ‘Anti-Communist’ legislation, ‘whites only’ participation legislation and ‘banning’ of its members and would also cease to exist.

Dr Maurice McGregor, our eyewitness Torchman to the demise of the Torch offers a slightly different view on The Torch Commando, he did not see the collapse as been caused by suppressive actions of the National Party and he differs from the view that the Torch collapsed because the United Party tried to pull the Torch to ‘toe the line’ on with its policies creating disunity and ultimately become directionless.

What Dr Maurice McGregor recalls is a ‘implosion’ – not because of the United Party, but because of an anathema towards Nazism – an internal moral dilemma. This is what he said;

“The torch commando eliminated itself at the peak of its power through fear of creating a paramilitary organization like the Greyshirts in Germany. I was in was actually the last March that the organization took part in. We marched in the dark to ‘protect’ a United party meeting and had to survive a shower of stones coming in over our heads. As the discussion went afterwards, we had the personnel and could very easily have put together a group to deal with such thugs, but the leadership, as indeed many of us, we’re extremely nervous of creating a private army which would take paramilitary action and considered that such an act would be an antidemocratic thing. So, the organization dissolved itself.”

He summarises the Torch very accurately, per the Torch’s initial role – that of a ‘Political Pressure Group’ and not that of a political party whose mandate is the machinery of political reform, nor that of a political movement seeking reform through social dissonance and revolution. A Political Pressure Group is defined as a special interest group which seeks to influence Government policy in a particular direction. Such groups do not seek Government control or responsibility for policy. Maurice summarised The Torch Commando as;

“It was … a history rewrite with a very definite slant … to try to define the slant … the Torch Commando was there primarily to check erosion of the democratic process, and it did try to protect the very limited coloured vote in the Cape. It also opposed various applications and extensions of Apartheid. But it kept away from advocating any real reform, saying that that such decisions should be made by a functioning democratic system.”

The Torch’s demise as a comprehensive and organised ‘whole’ of ‘whites in opposition to Apartheid would see future white political resistance terminally fractured, isolated and largely ineffective. This is the first significant mass of ‘pro-democracy’ whites against Apartheid as a ‘whole’ – it would not be given a political voice again as a ‘whole’ again until F.W. de Klerk’s Yes/No referendum in 1992.

To wrap it up Louis Kane-Berman and some colleagues would use some of the remaining funds in the Torch Commando’s financial accounts for donations – which they gave to the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), the Black Sash and St Nicolas Home for Boys. Donations were also made to Chief Albert Luthuli, the President of the ANC and to Professor Z.K. Matthews at Fort Hare University.

Michael Fridjhon concluded his paper on The Torch Commando in 1976 stated:

“The Torch became nothing. It was a bubble which burst over the South African political scene. It vanished almost as suddenly as it emerged”.

In Conclusion

However, nothing is further from the truth, with respect to Michael Fridjhon he would have been barred from accessing information on Torch Commando and its members because of Apartheid policies banning such information an access in 1976 – he would have been unable to see ‘the golden thread’ – who from The Torch Commando did what after it folded – what happened next? We can research this now – so, let’s pick up where he would have been unable to and ask ourselves what happens next – what legacy does the Torch Commando leave, where do the ‘dots’ connecting its thread to the armed and political struggle go?

The Torch Commando for the most part was ‘written out of history’ by The National Party and remains ‘written out’ for political expedience by the current government. It is a ‘inconvenient truth’ as it highlights a mass movement of pro-democratic white people not in alignment with Apartheid. It challenges the prevailing malaise of thinking in South Africa – that everything prior to 1994 was ‘evil’ and white South Africans must therefore share a collective ‘guilt’.

The Torch Commando stands testament to the fact that the majority of white people in South Africa did not vote for Apartheid and as much a quarter of the entire voting bloc – 250,000 white people actively hit the streets in protest against Apartheid. It’s a prevailing and undisputed fact that the Torch Commando protests are the first mass actions against Apartheid, they pre-date the African National Congress’ Defiance Campaign – so as to a inconvenient truth to the current ANC narrative, the first significant mass actions where led by white South Africans and not black South Africans – a testament to the fact that the struggle against Apartheid was an ideological and moral struggle and not one of race.

The Torch Commando – next instalment

What follows next is called ‘The Smoking Gun’ – please click through to this Observation Post link which covers in this phase depth.

The Torch Commando – Part 5; The Smoking Gun

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References:

Written testimony of Dr Maurice McGregor submitted to Peter Dickens: 20th December 2016.

The Torch Commando & The Politics of White Opposition. South Africa 1951-1953, a Seminar Paper submission to Wits University – 1976 by Michael Fridjhon.

The South African Parliamentary Opposition 1948 – 1953, a Doctorate submission to Natal University – 1989 by William Barry White.

The influence of Second World War military service on prominent White South African veterans in opposition politics 1939 – 1961. A Masters submission to Stellenbosch University – 2021 by Graeme Wesley Plint

The Rise and Fall of The Torch Commando – Politicsweb 2018 by John Kane-Berman. Large extracts taken from the late John Kane-Berman memoirs of his father Louis Kane-Berman with the kind permission of the Kane-Berman family.

Raising Kane – The Story of the Kane-Bermans by John Kane-Berman, Private Circulation, May 2018

The White Armed Struggle against Apartheid – a Seminar Paper submission to The South African Military History Society – 10th Oct 2019 by Peter Dickens

Sailor Malan fights his greatest Battle: Albert Flick 1952.

Sailor Malan – By Oliver Walker 1953.

Lazerson, Whites in the Struggle Against Apartheid.

The White Tribe of Africa: 1981: By David Harrison

Ordinary Springboks: White Servicemen and Social Justice in South Africa, 1939-1961. By Neil Roos.

Related Work

Torch Commando Series – Part 1 The Nazification of the Afrikaner Right

Torch Commando Series – Part 2 The Steel Commando

Torch Commando Series – Part 3 The War Veterans’ Action Committee

Torch Commando – ‘New’ rare footage of The Torch Commando in action, the first mass protests against Apartheid by WW2 veterans.

The Torch Commando Series

The Smoking Gun of the White Struggle against Apartheid!

The Observation Post published 5 articles on the The Torch Commando outlining the history of the movement, this was done ahead of the 60th anniversary of the death of Sailor Malan and Yvonne Malan’ commemorative lecture on him “I fear no man”. To easily access all the key links and the respective content here they are in sequence.

In part 1, we outlined the Nazification of the Afrikaner right prior to and during World War 2 and their ascent to power in a shock election win in 1948 as the Afrikaner National Party – creating the groundswell of indignation and protest from the returning war veterans, whose entire raison d’etre for going to war was to get rid of Nazism.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The Nazification of the Afrikaner Right

In part 2, in response to National Party’s plans to amend the constitution to make way for Apartheid legislation, we outlined the political nature of the military veterans’ associations and parties and the formation of the War Veterans Action Committee (WVAC) under the leadership of Battle of Britain hero – Group Captain Sailor Malan in opposition to it. Essentially bringing together firebrand Springbok Legionnaires and the United Party’s military veteran leaders into a moderate and centre-line steering committee with broad popular appeal across the entire veteran voting bloc.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The War Veterans’ Action Committee

In Part 3, we cover the opening salvo of WVAC in a protest in April 1951 at the War Cenotaph in Johannesburg followed by the ratification of four demands at two mass rallies in May 1951. They take these demands to Nationalists in Parliament in a ‘Steel Commando’ convoy converging on Cape Town. Led by Group Captain Sailor Malan and another Afrikaner – Commandant Dolf de la Rey, a South African War (1899-1902) veteran of high standing their purpose is to raise support from Afrikaner and English veterans alike and they converge with a ‘Torchlight’ rally of 60,000 protestors and hand their demands to parliament.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The Steel Commando

In Part 4, in response to the success of The Steel Commando Cape Town protest, we then look at the rise of the Torch Commando as South Africa’s largest and most significant mass protest movement in the early 1950’s pre-dating the ANC’s defiance campaign. Political dynamics within the Torch see its loyalties stretched across the South African opposition politics landscape, the Torch eventually aiding the United Party’s (UP) grassroots campaigning whilst at the same time caught up in Federal breakaway parties and the Natal issue. The introduction of the ‘Swart Bills’ in addition to ‘coloured vote constitutional crisis’ going ahead despite ineffectual protests causes a crisis within the Torch. This and the UP’s losses in by-elections in the lead up to and the 1953 General Election itself spurs the eventual demise of The Torch Commando.

For the in-depth article follow this link: The ‘Rise and Fall’ of the Torch Commando

In Part 5, we conclude the Series on The Torch Commando with ‘The Smoking Gun’. The Smoking Gun traces what the Torch Commando members do after the movement collapses, significantly two political parties spin out the Torch Commando – the Liberal Party of South Africa and the Union Federal Party. The Torch also significantly impacts the United Party and the formation of the breakaway Progressive Party who embark on formal party political resistance to Apartheid and are the precursor of the modern day Democratic Alliance. The Torch’s Communists party members take a leading role in the ANC’s armed wing MK, and the Torch’s liberals spin off the NCL and ARM armed resistance movements from the Liberal Party. We conclude with CODESA.

For an in-depth article follow this link: The Smoking Gun

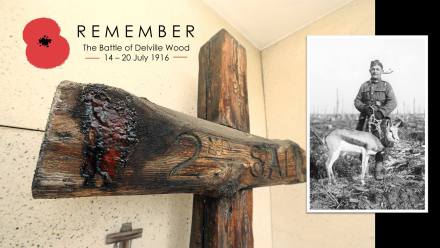

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

In South Africa we have two ‘living memorials’, one for the First World War, the annual running of the Comrades Marathon between Durban and Pietermaritzburg, and another for the Second World War, the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town. Sadly commonly referred to as the Red Cross Children’s Hospital, so not many people know of its wartime origin and its true intention.

In South Africa we have two ‘living memorials’, one for the First World War, the annual running of the Comrades Marathon between Durban and Pietermaritzburg, and another for the Second World War, the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town. Sadly commonly referred to as the Red Cross Children’s Hospital, so not many people know of its wartime origin and its true intention.

The history of the Springbok Legion as a political entity is fascinating – initially formed in 1941 by members of the 9th Recce Battalion of the South African Tank Corps, along with the Soldiers Interests Committee formed by members of the First South African Brigade in Addis Ababa, and the Union of Soldiers formed by the same brigade in Egypt.

The history of the Springbok Legion as a political entity is fascinating – initially formed in 1941 by members of the 9th Recce Battalion of the South African Tank Corps, along with the Soldiers Interests Committee formed by members of the First South African Brigade in Addis Ababa, and the Union of Soldiers formed by the same brigade in Egypt.

In reality, the Torch Commando constituted the first real mass “anti-Apartheid” protests and Adolph ‘Sailor’ Malan can be counted as one of the very first anti-apartheid ‘struggle’ heroes. Sailor Malan, a Battle of Britain hero and flying ace (one of the best pilots the Royal Air Force had during the war) returned to his homeland – South Africa in 1946.

In reality, the Torch Commando constituted the first real mass “anti-Apartheid” protests and Adolph ‘Sailor’ Malan can be counted as one of the very first anti-apartheid ‘struggle’ heroes. Sailor Malan, a Battle of Britain hero and flying ace (one of the best pilots the Royal Air Force had during the war) returned to his homeland – South Africa in 1946.

This eventually resulted in the fracturing of the Springbok Legion as a whole as moderate “white” members, who made up the majority of its supporters became disenchanted with its increasingly militant leftist rhetoric.

This eventually resulted in the fracturing of the Springbok Legion as a whole as moderate “white” members, who made up the majority of its supporters became disenchanted with its increasingly militant leftist rhetoric.

Sailor Malan’s political career was effectively ended and the “Torch” effectively suppressed by the National Party, so he returned to his hometown of Kimberley. Sailor then joined his local Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH) shell-hole (branch) in Kimberley and withdrew from politics, choosing instead the social and camaraderie of his like-minded colleagues in his ‘shell-hole’ and the ‘good life’ (he had a reputation as the ‘life of a party’).

Sailor Malan’s political career was effectively ended and the “Torch” effectively suppressed by the National Party, so he returned to his hometown of Kimberley. Sailor then joined his local Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH) shell-hole (branch) in Kimberley and withdrew from politics, choosing instead the social and camaraderie of his like-minded colleagues in his ‘shell-hole’ and the ‘good life’ (he had a reputation as the ‘life of a party’).

The campaign to purge the national consciousness of The Torch Commando, The Springbok Legion and Sailor Malan was highly effective as by the 1970’s and 1980’s the emergent generation of South Africans have little to no knowledge of The Torch or The Springbok Legion, it is highly unlikely that anyone today remembers Sailor Malan’s speech to 75,000 Torch Commando protesters in the centre of Johannesburg. The veterans community today, albeit very small, have kept his memory alive, Sailor’s MOTH shell-hole in Kimberley still remember this outstanding war hero very fondly to this day,

The campaign to purge the national consciousness of The Torch Commando, The Springbok Legion and Sailor Malan was highly effective as by the 1970’s and 1980’s the emergent generation of South Africans have little to no knowledge of The Torch or The Springbok Legion, it is highly unlikely that anyone today remembers Sailor Malan’s speech to 75,000 Torch Commando protesters in the centre of Johannesburg. The veterans community today, albeit very small, have kept his memory alive, Sailor’s MOTH shell-hole in Kimberley still remember this outstanding war hero very fondly to this day, Many older people will remember a time in the 50’s, 60’s and early 70’s, when on “Poppy Day” thousands of South African Legion members with their supporters would ‘sell’ paper red poppies raising funds for veterans in need in just about every major shopping centre all over South Africa. Some may even remember the South African Legion visiting their schools and explaining the meaning of the Poppy.

Many older people will remember a time in the 50’s, 60’s and early 70’s, when on “Poppy Day” thousands of South African Legion members with their supporters would ‘sell’ paper red poppies raising funds for veterans in need in just about every major shopping centre all over South Africa. Some may even remember the South African Legion visiting their schools and explaining the meaning of the Poppy. Simply put, even though the South African Legion (BESL) had taken an apolitical stance and chosen a cordial approach in dealing with the Nationalists, it still found itself coming into headlong confrontation with the National Party government, both in terms of its individual members’ politics but also in terms of the mandate given to it as the national body to look after Cape Coloured, Indian and Black South African veterans in need.

Simply put, even though the South African Legion (BESL) had taken an apolitical stance and chosen a cordial approach in dealing with the Nationalists, it still found itself coming into headlong confrontation with the National Party government, both in terms of its individual members’ politics but also in terms of the mandate given to it as the national body to look after Cape Coloured, Indian and Black South African veterans in need.

The ‘statutory’ associations i.e. the Infantry Association, Armour Association, Naval Officers Association, Gunners Association, Caledonian Regiments Association etc. etc. are combined and lumped with more newly sprung ‘broader’ veterans associations – the SADF Veterans Association, the South African Military Veterans Organisation ‘International’ (a spin-off from a Australia based SA veterans association) and more, each targeting the same veteran – all of whom exist under their own umbrella organisation – The Council of Military Veterans Organisations (CMVO).

The ‘statutory’ associations i.e. the Infantry Association, Armour Association, Naval Officers Association, Gunners Association, Caledonian Regiments Association etc. etc. are combined and lumped with more newly sprung ‘broader’ veterans associations – the SADF Veterans Association, the South African Military Veterans Organisation ‘International’ (a spin-off from a Australia based SA veterans association) and more, each targeting the same veteran – all of whom exist under their own umbrella organisation – The Council of Military Veterans Organisations (CMVO). This all in turn falls under the ‘Department of Military Veterans’ (DMV) a government department under the Minister of Defence which toes a very African National Congress (ANC) party political line in its media either shaming or ignoring the statutory veterans (especially the old ‘SADF’ members who make up the majority of the Department’s mandate and membership) and highlighting the deeds of the non statutory political party veterans, primarily ANC Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) veterans as noble ones instead (and these veterans are contentious at best).

This all in turn falls under the ‘Department of Military Veterans’ (DMV) a government department under the Minister of Defence which toes a very African National Congress (ANC) party political line in its media either shaming or ignoring the statutory veterans (especially the old ‘SADF’ members who make up the majority of the Department’s mandate and membership) and highlighting the deeds of the non statutory political party veterans, primarily ANC Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) veterans as noble ones instead (and these veterans are contentious at best).

Flight Lieutenant Adolph Gysbert Malan. (37604), Royal Air Force.

Flight Lieutenant Adolph Gysbert Malan. (37604), Royal Air Force. Acting Squadron Leader Adolph Gysbert Malan, DFC (37604), Royal Air Force, No.74 Squadron.

Acting Squadron Leader Adolph Gysbert Malan, DFC (37604), Royal Air Force, No.74 Squadron.

“I Fear No man”

“I Fear No man”