Let’s establish two things up-front about J.R.R. Tolkien the creator of ‘The Hobbit’ and the ‘Lord of the Rings’ trilogy, firstly he was a South African and secondly, he was a soldier. His formative years and war experience are the backdrop to the creative mind that produced the legendary sentence “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit” a mind that unleashed the worlds of Middle Earth, Mordor, Frodo Baggins, Sam Gamgee, Gandalf the Grey, Dragons, Mining Dwarves and not forgetting our ‘precious’ Gollum on us.

A ‘South African’

It’s seldom acknowledged, even in the country of his birth, that Tolkien was born in South Africa (technically however, he was born in the Orange Free State Republic). Tolkien was born John Ronald Reuel (J.R.R.) Tolkien in Bloemfontein on the 3 January 1892. His father, Arthur Reuel Tolkien was a bank manager, his parents left England when Arthur was promoted to head the Bloemfontein office of a British bank called The Bank of Africa which involved itself primarily in financing diamond and gold mining.

The reason for the move to the ‘colonies’ with The Bank of Africa was that it enabled Arthur to marry Mabel Suffield and support a family. So, before he was born, J.R.R Tolkein’s Mum and Dad were married in the Cathedral Church of St George the Martyr in Cape Town in the Cape Colony on 16 April 1891 and then moved on to the Orange Free State Republic.

The couple eventually reached the capital of the Free State – Bloemfontein, after a 32-hour train journey, Mabel was not impressed by the place. “Owlin Wilderness!… Horrid Waste!” she wrote of Bloemfontein. The independent Boer Republic capital at the time had a population of 3500, it was windy, dusty and treeless – however on the up-side the nearby veld still contained abundant game.

A picture of Church Street (currently known as Oliver Tambo Road) Bloemfontein, circa 1900

John Ronald Reuel (J.R.R.) Tolkien was born at Bank House in Bloemfontein, he was later baptised in the Anglican Cathedral of St Andrew and St Michael, one of the oldest churches in Bloemfontein. His third name ‘Reuel’ sounded so unusual that the vicar misspelt it in the baptismal register. One of his godparents was George Edward Jelf, the Assistant Master at Bloemfontein’s now legendary boys school – St Andrew’s College.

Tolkien had one sibling, his younger brother, Hilary Arthur Reuel Tolkien, who was also born in Bloemfontein on 17 February 1894.

Generally, the harsh African climate did not sit well with Mabel and the scorching Bloemfontein summer followed by freezing winter did not appeal to her at all. She took the boys on a short holiday to the seaside in the Cape Colony in 1894 – a holiday which Tolkien himself remembered vividly and had very strong impressions of the landscape.

Shortly afterward the sea-side trip Mabel took the boys on another holiday to England. Tolkien’s father was heavily engaged in work and was to join the family in England for the holiday later. The separation had a huge influence and Tolkien would later recall powerful separation anxiety; he recalled his father painting ‘A.R. Tolkien’ on their cabin trunk. Tolkien retained the trunk as a treasured in memory of his father.

They waited for their father to join them in Birmingham, but he never arrived. He had developed Rheumatic Fever in Bloemfontein and died from complications brought on by the illness. He was buried near the old Cathedral in Bloemfontein in what is now the President Brand Cemetery. For many years his grave was lost and was unmarked until in 1992 the Tolkien family was able to trace the grave and consecrate a new headstone.

With little to come back to Mabel decided not to return to South Africa and the young family settled in the hamlet of Sarehole near Birmingham

An African Influence

So how could South Africa possibly have influenced the wonderful mind of such a young J.R.R Tolkien having only spent 3 years there? People who study Tolkien (yup, there is a fraternity of Tolkienists who dedicate study to him and his books), point to a number of interesting instances which happened to him in South Africa which influenced his formative mind.

So how could South Africa possibly have influenced the wonderful mind of such a young J.R.R Tolkien having only spent 3 years there? People who study Tolkien (yup, there is a fraternity of Tolkienists who dedicate study to him and his books), point to a number of interesting instances which happened to him in South Africa which influenced his formative mind.

Firstly, he was kidnapped. Now that’s not common knowledge. An African male domestic helper in the Tolkien family employ named Isaak kidnapped baby Tolkien for a day to show him off to nearby villagers, Isaak had a great affinity to Tolkien and was immensely proud of the young lad – the family forgave him and funnily Isaak went on to name his first son Isaak Mister Tolkien Victor.

Secondly, he was bitten by a poisonous spider. Some sources point to a baboon spider and others point to a tarantula as the culprit who bit him on the foot when he was a toddler learning to walk, either way, very luckily, a quick-witted family nurse sucked the poison out.

Tolkien himself later said he had no real fear of spiders, however Tolkienist researchers claimed that this experience prompted Tolkien’s evil spirits in the form of huge venomous arachnids. In the Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings we read of battles with the horrifying giant Spiders, Shelob and Ungoliant. When asked to comment on this theory, Tokien himself didn’t confirm or deny it, saying only that the researchers were “welcome to the notion”.

Thirdly, and this is the most significant influence South Africa made on Tolkien is his future love of languages – a love which led him to imagine entirely new invented languages – there is hardly a hard core Hobbit fan out there who is not swept away with the Elvin language. Of this influence there is no denial and the language which did it – Afrikaans. Yup, believe it.

Tolkien’s father learned to speak a little ‘Dutch’ in his local dealings and Mabel interacted with local Bloemfontein residents – English and Afrikaners alike. She even performed in amateur plays staged by the Fischers and the Fichardts, two of the most prominent Free State families.

In one of the earliest photographs of J.R.R. Tolkien he can be seen with in the arms of his Afrikaner nurse. He was also surrounded by servants all of whom spoke Afrikaans. His nurse taught him some of her language and phases and Tolkien would later say of himself – “My cradle-tongue was English with a dashing of Afrikaans”.

Photograph of the Tolkien family in Bloemfontein, November, 1892 with J.R.R in the hands of his nurse

Tolkien would develop his love for new languages and later studied Latin and Greek. He went on to get his first-class degree at Exeter College, specialising in Anglo-Saxon and Germanic languages and classic literature.

In The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, he invented an entirely new language for his elves, Quenya – also known as Qenya or High-Elven, with its grammar rooted in Germanic languages, Greek and Latin. Tolkien compiled the “Qenya Lexicon”, his first list of Elvish words, in 1915 at the age of 23, and continued to refine the language throughout his life.

In The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, he invented an entirely new language for his elves, Quenya – also known as Qenya or High-Elven, with its grammar rooted in Germanic languages, Greek and Latin. Tolkien compiled the “Qenya Lexicon”, his first list of Elvish words, in 1915 at the age of 23, and continued to refine the language throughout his life.

Ah, but he was just ‘too young’ for South Africa to have any influence whatsoever would be the chorus of the sceptical readers of this article, he was only 3 years old when he left – not so, we are dealing with a brilliant mind and consider this, by the time he was 4 years old Tolkien could read and he could write fluently very soon afterwards.

Back in England tragedy was to strike the Tolkin boys again, when their mother Mabel also died in 1904, and the Tolkien brothers were sent to live with a relative and in boarding homes, with a Catholic priest assuming guardianship in Birmingham.

Tolkien had a highly imaginative upbringing in England and by October 1911 he began studying at Exeter Collage at Oxford University. He initially started with classics but switched to Languages and Literature, graduating in 1915 with first-class honours.

World War 1

Being a soldier is one of Tolkien’s biggest influences and of that there is little doubt, war awoke in Tolkien a taste for a fairy story which reflected the extremes of light and darkness, good and evil which he saw around him, especially when you consider the battles he took part in and witnessed.

Being a soldier is one of Tolkien’s biggest influences and of that there is little doubt, war awoke in Tolkien a taste for a fairy story which reflected the extremes of light and darkness, good and evil which he saw around him, especially when you consider the battles he took part in and witnessed.

World War 1 broke out whilst Tolkien was at university. He elected not to join until he finished his degree. Upon graduating Tolkien immediately found himself in the British Army in July 1915, volunteering to join up. Aged 22 ,he joined the 11th Lancashire Fusilliers and studied signalling, emerging as a 2nd Lieutenant, he married whilst in the Army in March 1916 and in short time, by June was ordered to go to France to take part in the Battle of the Somme, at the time he said of the order “It was like a death,”

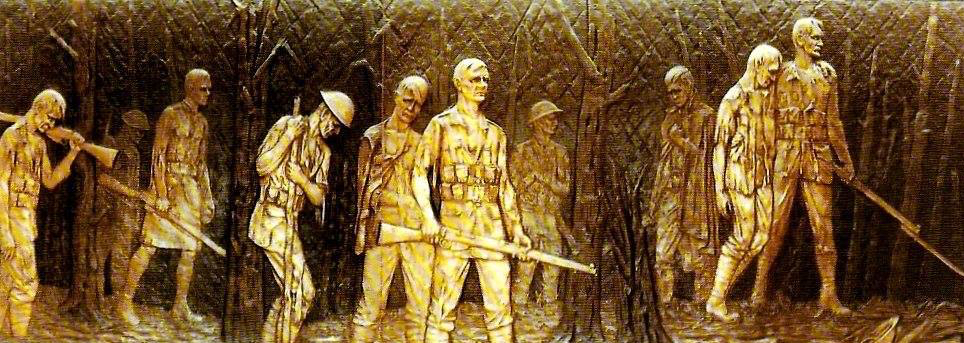

The Battle of Somme in 1916 was singularly the biggest bloodletting of World War 1 as one million men (get your head around that) on both sides were either killed or wounded as the British advanced a front along the Somme river for only 7 miles. The Battle of the Somme is no doubt the background to Tolkien’s future Middle Earth – Mordor (the Black Land and Quenya Land of Shadow) and the realm and base of the arch-villain Sauron.

Battle of Albert. Roll call of the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers in a communications trench. IWM image copyright

Fortunately for Tolkien he was spared from the first Somme assault (unlike many of his university educated officer class friends and colleagues who were mowed down), the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers were held in Reserve. When sent ‘over the top’ the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers helped capture the German stronghold at Ovillers two weeks later.

Tolkien was appointed the battalion signalling officer and spent the next three months in and out of trenches. The biggest inspiration for Tolkien’s future The Lord of Rings lies in his respect for the ordinary British infantryman under such intense adversary, these infantrymen would later be the bedrock for Tolkien’s loyal, brave and resilient hobbit – Samwise Gamgee.

Wiring party of the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers going up to the trenches. Beaumont Hamel, July 1916. IWM copyright

In late October, after seizing a key German trench, the Fusiliers were sent on to Ypres. But Tolkien was ‘lucky’ to be spared the slaughter in Belgium, a tiny louse bite gave him trench fever, so he landed up in a Birmingham hospital and here he started writing about mechanistic dragons, inspired by the invention of the military tank in warfare and formulating Mordor in his mind instead.

Tolkien spent the rest of the war in and out of hospital and training troops in Staffordshire and Yorkshire. Here in 1917, whilst walking in the woods with his wife he was inspired to write the love story of the fugitive warrior Beren and the elven-fair Lúthien.

In all Tolkien summed up war in the trenches as “animal horror” and he was not far wrong.

More South African twists and turns

After the war ended in November 1918 the lure of South Africa endured and Tolkien in 1920 applied for a professorship of English Literature at the University of Cape Town (UCT), and was to be sponsored by De Beers Mining consortium, His application was approved, but, in the end, he had to decline the offer for family reasons and retained his post as reader at the University of Leeds and was later appointed professor at Oxford.

Tolkien settled in to write the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings Trilogy, however war (and South Africa) was never to really leave him. When World War 2 came about, his youngest son Christopher joined the Royal Air Force and, in 1944 he was dispatched to South Africa to train in Kroonstad (also in the Orange Free State) to train as a fighter pilot and he was later moved to Standerton.

Christopher Tolkien (marked with X) training in South Africa 1944

J.R.R. Tolkien resumed his work on The Lord of the Rings and sent chapters from the future book to his son in South Africa, in a letter he told Christopher that he wished he could travel to South Africa – the country of his birth. He wrote of his curiosity in Africa and wrote to Christopher of the “curious sense of reminiscence about any stories of Africa, which always moves me deeply. Strange that you, my dearest, should have gone back there…’

To say that Christopher or his experiences did not have any influence on The Lord of the Rings, consider that after the war in 1950 he become a freelance tutor completing a B.Litt and worked very closely with his father through the creation of The Lord of the Rings and later works, and he was given the task of creating the original maps for the first edition of The Lord of the Rings.

The truth is, South Africa never really left J.R.R. Tolkien, he was native to it, intrinsically linked to his land of birth, ever wanting to return to it and it continued to have a deep influence on him all his life.

Legacy in South Africa

So where are we with remembering one of South Africa’s most successful authors of all time? The reading is grim I’m afraid. Apart from the generally Hobbit crazy Hogsback village and nature park in the Eastern Cape there is little else. Hogsback has used the Tolkien/South Africa link to an insane level naming just about everything in the nature park after something to do with The Lord of the Rings, but it’s an indirect link – there is no evidence that Tolkien never visited Hogsback. The biggest disappointment however is Bloemfontein where there is a direct link – he is after all one of their most famous ‘sons’ – and a very big tourist opportunity for the city.

Hogsback – Tolkien’s Middle Earth in the Amathole Mountains?

However, in Bloemfontein the Tolkien Society is now defunct, the municipality on Tolkien’s birth centenary mooted a Tolkien walk (to see places he grew up in etc) but that never really materialised. There is a plaque at the Church in which he was baptised, but that’s about it. Travel guides list Tolkien’s father’s grave as ‘too dangerous’ to visit. The brass plaque on commemorating his birthplace was stolen and never replaced.

In Conclusion

This general apathy to Tolkien in South Africa is best summed up UK journalists from the Mail and Guardian who made their way to Bloemfontein when Peter Jackson launched his epic movie trilogy of Lord of the Rings – they expected to get a scoop on South Africans embracing what is arguably one of their most famous authors, if not the most famous. Instead they were surprised to learn that the average modern South Africa did not know Tolkien was South African born and here is the key part – when interviewed they felt that The Lord of the Rings was ‘European’ mythology and had nothing to do with African culture, so they deduce that was simply not a real African.

Therein lies the essence, South African educators today simply dismiss anything with a ‘colonial’ heritage, including what is arguably one of the best-selling authors the entire world has ever seen. The truth is Tolkien was South African, his biggest influence was that of the World War 1, a war that South Africa also took part in, and in the Battle of the Somme his original ‘countrymen’ – South Africans were defending Deville Wood a little way down the Somme salient shoulder to shoulder with him.

The lack of adoption of a South African of British heritage like Tolkien in his country of birth is a travesty to understanding history correctly, South Africa is made up of many cultural parts and all its history needs to be preserved, not just one or the other.

I for one hope this missive goes a little way to re-education, and as a fellow South African and military veteran I salute you John Ronald Reuel Tolkien.

Written and Researched by Peter Dickens

References: Tolkien’s War: Mordor Was Born in WW1 by Mark Shiffer, Tolkien Gateway on-line, J.R.R. Tolkien Biography by Biography.com Editors, South African History on-line. A plaque, a Hobbit hotel and a JRR Tolkien trail that’s petered out … David Smith, ‘Africa… always moves me deeply’: Tolkien in Bloemfontein by Boris Gorelik. Bloemfontein: On the trail of Tolkien by David Tabb.

With thanks to Norman Sander for assistance on the edit.

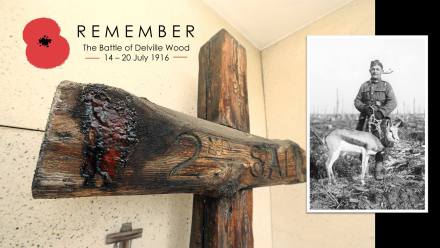

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

This South African’s Victoria Cross turns 100 on the 21/22 March 2018, so today we honour another true South African hero and Victoria Cross recipient, and this man, Captain Reginald Frederick Johnson Hayward VC MC & Bar is one very extraordinary South African.

This South African’s Victoria Cross turns 100 on the 21/22 March 2018, so today we honour another true South African hero and Victoria Cross recipient, and this man, Captain Reginald Frederick Johnson Hayward VC MC & Bar is one very extraordinary South African.

CITATION

CITATION

Reginald worked at the British Broadcasting Corporations (BBC) Publications Department from 1947 to 1952 and as games manager of the Hurlingham Club from 1952 to 1967.

Reginald worked at the British Broadcasting Corporations (BBC) Publications Department from 1947 to 1952 and as games manager of the Hurlingham Club from 1952 to 1967.

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was scho

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was scho

“On behalf of The Royal British Legion South African Branch I would also like to welcome all here today, it is our privilege to honour the South African sacrifice during the Somme offensive – especially at Delville Wood just a short distance from this memorial.

“On behalf of The Royal British Legion South African Branch I would also like to welcome all here today, it is our privilege to honour the South African sacrifice during the Somme offensive – especially at Delville Wood just a short distance from this memorial.

I would like, if I may, to talk about why is the Battle of the Somme, something that occurred 100 years ago, is so important to us as veterans?

I would like, if I may, to talk about why is the Battle of the Somme, something that occurred 100 years ago, is so important to us as veterans?

At 05.30 in the morning of 11 November 1918 the Germans signed the Armistice Agreement in a remote railway siding in the heart of the forest of Compiègne. Soon wires were humming with the message : ‘Hostilities will cease at 11.00 today November 11th. Troops will stand fast on the line reached at that hour…’.Thus, at 11.00 on 11 November 1918 the guns on the Western Front in France and Flanders fell silent after more than four years of continuous warfare, warfare that had witnessed the most horrific casualties.World War One (then known as the Great War) had ended.

At 05.30 in the morning of 11 November 1918 the Germans signed the Armistice Agreement in a remote railway siding in the heart of the forest of Compiègne. Soon wires were humming with the message : ‘Hostilities will cease at 11.00 today November 11th. Troops will stand fast on the line reached at that hour…’.Thus, at 11.00 on 11 November 1918 the guns on the Western Front in France and Flanders fell silent after more than four years of continuous warfare, warfare that had witnessed the most horrific casualties.World War One (then known as the Great War) had ended.