On the 11/11/2018 – exactly 100 years after the end of World War 1 on the 11/11/1918, at the exact minute the guns were silenced on the Western Front in 1918, i.e. 11 am, a group of South African veterans stood to attention in London. They were all taking part in the ‘Cenotaph Parade’ and whilst Big Ben tolled 11 times they reflected during the two minutes silence.

The minutes of reflection and silence was signalled by Artillery Guns whose shots reverberated over London as they marked the beginning of the silence period and the end. The guns had been fired from the Horse Guards Parade Ground by The King’s Troop – just opposite the South African contingent now standing in file in Whitehall with all the other arms of service, regiment, veteran and remembrance associations waiting to march past the Cenotaph.

Guns of the King’s Troop fired from the Horse Guards Parade Ground to signal 2 minutes silence at the Cenotaph Parade 2018

The retort of the gun literally shattered the cacophony of London’s noise, bringing absolute silence and in so bringing into sharp focus why the South African veterans were there – honouring countrymen who had given their all during World War 1 and in the future wars to come – and it also put perspective on the seven-year long journey they had taken to get there. Nothing in life is simple and nothing can be taken for granted – and the representation of South Africans on this specific parade, on this specific date was no different.

The historical journey of South African veteran contingents marching past the cenotaph in London had not been a continuous one, the early footsteps left by South African First World War veterans in recognition of their comrades lost had been reaffirmed by their Springbok brothers of the Second World War. However by the 1960’s the footprints came to an abrupt end and the South African veterans were no longer seen at this parade for the next 5 full decades to come, the story of South African commitment and sacrifice to crown during World War 1 and World War 2 fading quickly in the British collective memory.

For these veterans, to stand on this parade in London on this day in 2018, represented as a South African military veteran, proudly wearing the insignia, blazer and beret of South African Legion of Military Veterans is something. Think about it, and put it fully in perspective, they finally stood to commemorate South African sacrifice at the Centenary of the end of World War 1, when for a full half Century of that Century there had been no proper annual South African contingent at this prestigious parade – at all.

Here, on the Centenary of the World War 1’s Armistice in London – the South African Legion stood proud in its rightful place as the primo (the first) South African Veteran’s Association (the SA Legion is also nearly 100 years old itself). It was also the only South African affiliated veteran association at this climax to the centennial celebrations – the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade. A lot as to representing South African sacrifice was on the shoulders of this relatively small contingent of South African Legion veterans wearing the Legion’s (and country’s) green and gold.

South African veteran contingent in 2018 at the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade to commemorate 100 years since the guns fell silent in 1918

So what happened to the South African representation in the past – why did it stop for five decades? How and when was it re-started? Why only the Legion? Why only now and what does the future for South African representation at this parade hold?

More to that, who in South Africa should care, so what – what is the importance of London’s Cenotaph to South Africans anyway?

Why London’s Cenotaph?

So what’s so important about London’s Cenotaph in relation to the other World War 1 monuments the world over, including many in South Africa itself? Look at it this way, the Cenotaph in Whitehall is the epicentre of ‘remembrance’ of the First World War – for everyone, the world over.

Before the end of World War 1, based on the Red Cross officer Fabian Ware’s recommendation in 1917 the British government and The Imperial War Office, made an extraordinary decision, no British or Commonwealth fallen would be repatriated back to their country of origin. They would be buried in the country where they fell and their graves, honour roll and monuments would be looked after by a Graves Registration Commission – which we now know as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC).

A South African nurse places a wreath on her brother’s grave during the South African Brigade’s memorial service at Delville Wood, 17 February 1918.

This decision was controversial and it caused absolute consternation, the United States of America repatriated their war dead from the western front back to the USA, even the French war dead were repatriated back to their villages or towns. It was ‘back home’ that family, friends and community could look after their dead – conduct a burial, and the grave could stand as a physical presence of the loved one to pay respects and remember.

With British and Commonwealth war dead now not ‘coming home’ – how were people to remember? Where could family and friends go – not everyone could go to France, Belgium, Turkey and the myriad of countries the British and her Empire fought the war in to visit their lost loved one? There’s more, even to people who could afford to repatriate their dead to the family plot could no longer do so, let alone those who could not – and officers and men were now buried side by side, with no distinction given to rank, class or race – for a society breaking down Imperial barriers this was revolutionary thinking – but for a part of that society still bent on class differentiation it was an outrage.

A solution to tangibly meet this need and bring the entire remembrance ritual and service back to the United Kingdom was urgently needed, and it needed to be one which remembered all who were sacrified in the service to crown – Great Britain, the Dominions (Ireland, Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand) and all the other British Colonies, Protectorates and Territories.

The solution came in an unintended format, a temporary cenotaph monument, made from plaster and wood had been designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and erected for the London Victory Parade on the 19th July 1919 (to commemorate the Treaty of Versailles). There would be a ‘hollow square’ formed around the structure (as would happen in the field when soldiers hold a drum head service) and the Cenotaph would then act as the ‘Drum head’ – symbolising a tomb.

Sir Edwin Lutyens’ temporary Cenotaph for the Victory Parade in 1919

The temporary structure with its words ‘The Glorious Dead’ surprisingly met with great public enthusiasm desperately seeking a place to mourn, it became an icon, a beacon – finally there was a physical structure in England itself to which they could remember all the dead, lay wreaths and flowers to lost comrades, brothers, sisters, mothers and fathers. After the parade finished and for some time to come the base of the temporary structure was continuously covered with flowers and wreaths by members of the public. Public pressure mounted to retain it, and the British War Cabinet decided on 30 July 1919 that a permanent replica memorial made of Portland stone should replace the wooden version and be designated Britain’s official national war memorial.

The permanent stone structure of the Cenotaph in Whitehall was unveiled in a ceremony by King George V on the 11th November 1920 with the arrival of gun carriage bearing the coffin of an ‘Unknown Warrior’ at 11 am. In another groundbreaking move to symbolise remembrance a grave marking an ‘unknown’ british soldier was randomly selected (and it could have been anyone, even possibly someone from the Commonweath in a British unit – who knows) and opened in France, this simple soldier, a ‘commoner’ known only unto God was repatriated to England to be buried amongst Kings at Westminster Abby and he was afforded a King’s funeral procession from the Cenotaph

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Now in the west end of the Naive at Westminster Abby, the tomb of the Unknown Warrior has two fine traditions – you cannot walk over it and at any Royal wedding that takes place in Westminster Abby, the bride’s wedding bouquet is always left by the bride on the tomb itself – it’s this lucky chap who gets to catch the royal bouquet. The text inscribed on the tomb is taken from the bible (2 Chronicles 24:16): ‘They buried him among the kings, because he had done good toward God and toward his house’.

The ‘Cenotaph’ in Whitehall is literally the epicentre of ‘Remembrance’ – it is the central grave marker that remembers all the names of British and Commonwealth fallen who were not repatriated ‘back home’ – and the central Whitehall Cenotaph was to be replicated in Canada, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa (Durban, Cape Town and Johannesburg all have their own ‘cenotaph’) as the concept fanned out.

In the United Kingdom the South Africans were special, a South African hospital complex existed in Richmond (west London) treating WW1 wounded, and in addition to commemorating South African sacrifice at the main Cenotaph in Whitehall, a second Cenotaph – to the design of Sir Edwin Lutyens’ one in Whitehall, with a South African UDF ‘Springbok’ emblem on the top and ‘Our Glorious Dead’ in English and Dutch written on it was erected in Richmond and unveiled by Jan Smuts.

All of this, the concept of the Whitehall cenotaph and even the South Africa’s own cenotaph in London would eventually be lost to South Africa, for half a century, and it’s still lost to many South Africans – so how did that happen?

South African Pilgrimages

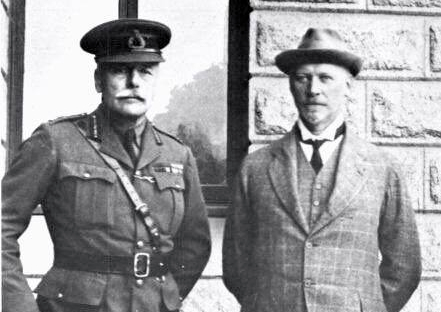

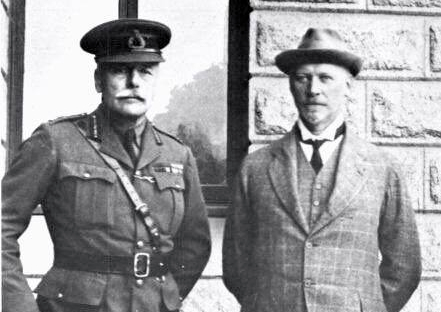

After World War 1 ended, a number of various returned services i.e. veterans associations came into existence all around Britain and the Commonwealth. These were all consolidated in a historic meeting held by a newly formatted umbrella body – The British Empire Services League (BESL), and the inaugural meeting took place in Cape Town, South Africa in 1921. Two people were to play a key role in this consolidation of veteran associations and to a large degree centralising ‘remembrance’ under one guiding body – Field Marshal Earl Haig and General Jan Smuts.

Field Marshal Haig and General Smuts at the inaugral meeting of The British Empire Services League in Cape Town 1921

This makes South Africa the epicentre of what is now the Royal Commonwealth Ex-Services Leagues (RCEL) and the founding partners are the Royal British Legion, Royal Canadian Legion, Royal Legion Scotland, South African Legion, Returned Services League Australia and the Royal New Zealand Returned Services Association.

Relevance to the Cenotaph in Whitehall? Well, it’s the Royal British Legion, the brother association of The South African Legion, which manages the Whitehall Remembrance Sunday Cenotaph parade and all the key associated remembrance activities in the United Kingdom.

After the South African Legion was formed in 1921 it went about conducting annual ‘pilgrimages’ for veterans of The First World War and families of the South African fallen to go to Europe and make the ‘connection’ with their loved ones who did not come home.

The South African Legion’s pilgrimages to the United Kingdom often took place over the Remembrance period in November, this sometimes involved a parade in Portsmouth at the memorial there to the men lost on the SS Mendi. They regularly held a parade at the South African Cenotaph in Richmond London, and annually, on Remembrance Sunday they participated in the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade as guests of The Royal British Legion and laid a wreath. The pilgrimages were almost always linked up with visits to Delville Wood in France and Menin Gate in Belgium.

The South African Legion’s pilgrimages to the United Kingdom often took place over the Remembrance period in November, this sometimes involved a parade in Portsmouth at the memorial there to the men lost on the SS Mendi. They regularly held a parade at the South African Cenotaph in Richmond London, and annually, on Remembrance Sunday they participated in the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade as guests of The Royal British Legion and laid a wreath. The pilgrimages were almost always linked up with visits to Delville Wood in France and Menin Gate in Belgium.

These SA Legion pilgrimages expanded after the Second World War somewhat, and South African veterans of both World War 1 and World War 2 in the 1950’s regularly took part in the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade on Remembrance Sunday as well as visiting the chapel and South African cenotaph in Richmond.

Half a century of wilderness

The annual laying of a South African wreath and veteran participation as a south african contingent at the Whitehall Cenotaph parade on Remembrance Sunday came to an end from 1961.

In 1960, H.F Verwoed and the Afrikaner Nationalists, now in consolidated power in South Africa having changed the constitution, pressed for a ‘Republic’ referendum which they won on the narrowest of margins by gerrymandering the vote – ensuring that whites only, and Afrikaner whites in particular, had the only decision on the future of South Africa’s status in the world, and especially its relationship with the United Kingdom – all the other communities in South Africa, the vast majority of her people – coloured, Indian and Black were excluded from the decision to change South Africa’s Dominion status – and all of them, including Nelson Mandela expressed solid opposition to it.

Opposition to the establishment of a South African Republic and subsequent removal from the Commonwealth

This was followed one year later in 1961 when as a newly minted independent Afrikaner Republic, the Afrikaner Nationalists removed South Africa from the British Commonwealth of Nations amid heavy criticism of their Apartheid policies by all the member states. The Sharpville Massacre had just taken place in 1960, opposition political groupings had been banned in the wake of Sharpville and the beginning of the 1960’s saw South Africa embarking on an internal armed struggle.

How did the British establishment react to it all in relation to their Cenotaph Parade? The answer – no differently to the way they now deal with Zimbabwe as a ‘rogue’ state outside the Commonwealth. They simply removed South Africa’s status from the Dominion and Commonwealth High Commission wreath layer line up at the beginning of parade. If you consider that they had no choice really – South Africa was no longer a Dominion and no longer part of the Commonwealth ‘club’ – so had no place, and given Apartheid South Africa could not really be afforded a special status on a world stage – such was the politics of the day.

In the end it was the Nationalist South African goverment who removed the country from the Commonwealth, not the other way round and it was the government of South Africa who paid scant regard to this sacrifice – seeing it as and act of treachery in support of the hated British instead, not the other way round.

But what about sacrifice and veterans remembrance – here the Royal British Legion came to the rescue in what was turning out to be bad news all around for South Africa and agreed that in the absence of South African representation they would lay the wreath on behalf of South Africa.

What followed was an unprecedented absence of over fifty years, in South Africa the SA Legion as the ‘national body’ for veterans and all related veteran organisations with Commonwealth and British links and shared heritage, including the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), all went into steady decline. The newly reconfigured South African Defence Force under the ideals of Republic went on to insidiously remove or relegate to secondary status all the deeds of bravery, heroes, insignia, heritage, history, medals and any other links to the United Kingdom. In effect the South African veterans of World War 1 and World War 2 now found themselves marginalised by the government – victims of Apartheid in effect.

This short Pathé Newsreel of the time explains the gravity of the decision to leave the Commonwealth and make South Africa a Republic very well, take the time to watch it.

The removal of South Africa from the Commonwealth spurred ‘The Springbok’ magazine, the South African Legion’s mouthpiece to lead with a headline ‘What Now!’ The truthful answer – not much! Government finances were gradually squeezed off, recruits from the armed forces were squeezed off, the poppy appeal gradually losing its momentum and relevance in South Africa as catastrophic and seismic political events in South Africa over took it.

In this general decline in relevance outside the commonwealth, decline in national party government support for old ‘union defence force’ veteran affairs and decline in public finance from donations – was the decline in SA Legion’s annual Pilgrimages to Europe, and with that general decline in just about everything, eventually also went the annual laying of the South African veterans wreath by the Royal British Legion at the Whitehall cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday.

1994 is significant in many ways, South Africa rejoined the British Commonwealth of Nations and was reinstated in things like the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade – and today the South African high commissioner joins the wreath party with all the old and current dominions i.e. Canada, Australia, India and New Zealand and given first honour to lay their wreaths ahead of all other Commonwealth member states. It stands to reason – these were the key contributors to the British military advance – in World War 1 and World War 2 (missing from this line up is Zimbabwe – which continues to be controversial as they continue to remain outside the Commonwealth – as South Africa had).

But what of the South African military veterans component of the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade itself – the critical connection of this contingent to the remembrance of their brothers in arms’ sacrifices – marking the recognition of their graves on foreign soil by passing the epicentre memorial of Remembrance in London – even as late as 2011, no South African identified contingent of veterans was properly represented. The Canadians and even the USA, Czech Republic and Poland have had representation in the past 50 years – but not the South Africans.

Why?

Reconstituting South African veteran representation in the UK

I arrived in the United Kingdom in 2010 after a stint in Australia, whilst in Australia – as a South African military veteran – I had joined SAMVOA, the South African Military Veterans of Australasia and I was amazed at the camaraderie and inclusion South African veterans received from the Returned Services League of Australia (RSL), we were happily included in the annual state ANZAC Day parades and afforded all the privileges of RSL members. The historical military links between South Africa and Australia forged during WW1 and WW2 remembered and stronger than ever. The open gratitude of the Australian community expressed to all veterans – Australian and just about anyone who has served in a statute force with a link to Australia was something to behold.

On arrival in the U.K. I tried to make contact with a South African Council of Military Veteran Organisation affiliated SAMVOA equivalent to participate in the London Cenotaph Parade, only to discover that no such organisation existed. I watched the cenotaph parade on telly, gob-smacked to see visiting US Marine veterans on parade and not a South African in sight. Advances to find out the status of MOTH (Memorable Order of Tin Hats) shellholes in the UK were met with disappointment – they had no marketing and were closing down shellholes hand over foot and had even done away with the enshrined regulations behind the order – that is it was a ‘Order’ for ‘Combat/Operational statutory force military veterans’ only. However civilians and veterans alike could now join the MOTH Order in the U.K. on an equal level – a change in enshrined MOTH qualifying criteria done to try to keep the order afloat in the U.K, which in its own odd way also serves to undermine the principles of the order.

On arrival in the U.K. I tried to make contact with a South African Council of Military Veteran Organisation affiliated SAMVOA equivalent to participate in the London Cenotaph Parade, only to discover that no such organisation existed. I watched the cenotaph parade on telly, gob-smacked to see visiting US Marine veterans on parade and not a South African in sight. Advances to find out the status of MOTH (Memorable Order of Tin Hats) shellholes in the UK were met with disappointment – they had no marketing and were closing down shellholes hand over foot and had even done away with the enshrined regulations behind the order – that is it was a ‘Order’ for ‘Combat/Operational statutory force military veterans’ only. However civilians and veterans alike could now join the MOTH Order in the U.K. on an equal level – a change in enshrined MOTH qualifying criteria done to try to keep the order afloat in the U.K, which in its own odd way also serves to undermine the principles of the order.

In 2011, after contacting the Royal British Legion to take part in the Cenotaph parade and been declined, I found myself as a single solitary South African veteran in a Trafalgar Square Royal British Legion (RBL) side-show for the general public laying a wreath in one of the ponds, and I noticed a single solitary MOTH member doing the same. That was the sum total of South African veteran representation in London on Remembrance Weekend.

Something had to be done, South African representation had slipped into nothing, general amnesia as to South African inclusion in any key state driven veteran or remembrance activity had set in across the entire establishment in the United Kingdom. Half a century of exclusion does that.

It also was not helped by the fact that from 1961 until that point in 2011 the South Africa embassy in the United Kingdom’s military attaché had not taken to much public Remembrance Representation work, nor had they established any significant links with The Royal British Legion or the Royal Commonwealth Ex-Services League. The old guard SADF attaché wanted nothing to do with these organisations and by the time the new guard SANDF attaché had come in they had no context or knowledge of the historical links, nor is it a current priority of theirs to reforge them (all too ‘colonial’ frankly).

As a result neither the South African military establishment or veteran associations were on the United Kingdom’s ‘remembrance Calender’ radar – at all. Not ‘recognised’ = not ‘invited’ = not ‘represented’.

In 2012 I colluded with a fellow South African veteran, Norman Sander, to address the matter, and looking at the history, links and association between The South African Legion and The Royal British Legion we felt a branch of The South African Legion in the United Kingdom was the route to go. Godfrey Giles, the then National President of The South African Legion agreed and a branch materialised in the U.K.

In 2012 I colluded with a fellow South African veteran, Norman Sander, to address the matter, and looking at the history, links and association between The South African Legion and The Royal British Legion we felt a branch of The South African Legion in the United Kingdom was the route to go. Godfrey Giles, the then National President of The South African Legion agreed and a branch materialised in the U.K.

All good right, representation at last – not on your nilly, there was a long and hard road to come. In 2012 we approached the RCEL and received our contingent tickets for the Cenotaph parade with open arms – then a mere two days later an apology arrived from a faceless bureaucrat to say that the Royal British Legion was ahead of itself in issuing the tickets and they had to be retracted – as South African Legion we were not ‘recognised’ (their term exactly).

This ‘non-recognition’ was utter balderdash, codswallop of the highest order and It was clear to us that within the British establishment there existed concern over South African military veterans – the whole ‘Apartheid legacy’ and ‘leaving the Commonwealth’ issue had extended its tentacles into an area where it had no place whatsoever – Remembrance of the Fallen.

Highly annoying, and before it blew up out of proportion, to overcome the problem a solution was presented by The Royal British Legion themselves. Come into the fold as a Royal British Legion branch, advance the relationship and values of The South African Legion and the Royal British Legion as a brother organisations, work up the credibility as veterans after a 50 year absence, create a South African presence at the Cenotaph parade and become ‘Recognised’ from within the establishment itself.

Highly annoying, and before it blew up out of proportion, to overcome the problem a solution was presented by The Royal British Legion themselves. Come into the fold as a Royal British Legion branch, advance the relationship and values of The South African Legion and the Royal British Legion as a brother organisations, work up the credibility as veterans after a 50 year absence, create a South African presence at the Cenotaph parade and become ‘Recognised’ from within the establishment itself.

Norman headed off to Africa to take on a new life, so the establishment of the South African Branch of the Royal British Legion and the formatting of the South African Legion in the United Kingdom fell on my shoulders. The Royal British Legion (RBL) had in effect thrown the South Africans a life-line and its a life-line the RBL would come through for the South African Legion and South African veterans time and again.

Back in the fold

Things had changed when it came to the annual Whitehall Cenotaph Parade in the past decade. It had become a well oiled institution with an unchanged parade order developed and refined over decades – and the same BBC announcer rolls off the ceremony with the same camera positions, year after year. No upstart ‘new-comer’ is going to reinvent this process in a hurry.

The parade is run in two parts by three separate institutions working together. In essence there is a ‘front part’ involving the Royal Family, Representatives of Her Majesty’s Armed Forces, Representatives of the House of Commons and House of Lords and the Representatives from all the Commonwealth states i.e. High Commissioners – including South Africa. They conduct the ceremony of wreath laying in the ‘hollow square’ around the Cenotaph i.e. in accordance with a drum head service. This bit is run by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) and the Department of Culture, Media & Sport.

The second part, the ‘back part’ which is the ‘march past’ the Cenotaph is generally run by The Royal British Legion. There are four general parts to it.

Firstly – British Service Associations (Regiment Associations and the like) who have served the ‘crown’ in the past and who continue to serve ‘crown’.

Secondly – Guests of the Royal British Legion, these are associations allowed to parade from time to time because of their links to Britain – and here we find a mixed bag of Polish veteran associations and Czech contingents (because of their association to The Battle of Britain) as well as invited US Marine veterans etc (D-Day association). ‘Guests’ come and go based on ticket demand (there is a limited allocation) and changing circumstances, and as our MOTH colleagues unfortunately found out at the centennial cenotaph parade this year when their tickets were not issued – a ticket in this category is by no means an assured one for annual parading.

Thirdly, there is the Royal British Legion themselves and their branches – and as an international brotherhood it is into this category that the South African Legion veteran contingent falls (and other countries represented within the RBL’s shere of influence itself – the Canadian Legion and veterans are a case in point).

South African Legion contingent march past the Whitehall Cenotaph in 2017

Finally there is a section open to the general public to participate, and in the case of the centennial this fell to a ‘ballot system’ to randomly select applications from members of the public for what is known as the ‘people’s march’.

The disappointment of 2012 behind us, 2013 found the South African veteran contingent represented for the first time as South African Legion when a handful of about 10 tickets were allocated to The RBL South African Branch, and this spiked a greater demand – and with that unfortunately came controversy within the South African veteran community in the U.K.

By 2014 there were 50 South African veterans represented as SA Legion at the Whitehall Cenotaph parade – a huge honour and reflection on the hard work been done to get South African representation at this parade over the line. The Royal British Legion had provided a ‘life boat’ for the South Africans towing it along in what was going to be a very troubled sea – and this RBL lifeboat would eventually even save the Delville Wood Centenary Parade in France for all South African military veteran associations in 2016.

Troubled seas ahead, and typically the South Africans were making waves in their own tub. From October 2014 to May 2015 the South African Legion in the U.K. found itself marred by a number of veterans wanting to pull the organisation in all sorts of conflicting directions. The old adage came true – put two South Africans in a room and they will come up with three political parties, and it all essentially boiled down to individual members trying to shoe horn Legion values (and even things like Legion dress code) into the values and codes of other veteran associations or even into their own individual perceptions and needs. The net outcome of this is that a few good men decided to jump out the life boat and try to swim it alone, highly regrettable and the unfortunate outcome is that they took their eyes off the ball, and none of them made it to the finish line on 11/11 at Whitehall.

Re-dedication of South Africa’s own Cenotaph in London

2014 saw more significant advances in bringing South African representation back to its rightful place in the UK – and that was the rededication of South Africa’s own Cenotaph in Richmond, London – and it was literally a case of ‘Lost and Found’.

The South African Hospital was established in Richmond Park in London in June 1916. In July 1918, it was amalgamated with the Richmond Military Hospital, to form the South African Military Hospital, in order to provide care for the large number of South African troops serving in the First World War.

Rededication of the South African War Memorial in Richmond London by The South African Legion

The South African Hospital and Comforts Fund Committee decided to erect a memorial to commemorate thirty-nine South African soldiers who were buried in Richmond Cemetery, which was at that time known as ‘soldiers corner’. The memorial carries an inscription in both English and Dutch (which was at the time a recognised official language of SA). Called ‘The South African War Memorial’ it was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and derives from Lutyens’ Cenotaph in Whitehall. Yes, the same one that rises to prominence on Remembrance Day in London.

The South African War Memorial was unveiled by General Smuts in June 1921 and it became the focus of South African pilgrimage throughout the 1920’s, 1930’s and 1940’s. Since then it became neglected and lay forgotten until 1981, when the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) agreed to take on the maintenance of the memorial on behalf of the Nationalist South African Government – who had expressed no interest in it whatsoever and did not even acknowledge it on the SADF’s list of South African war memorials overseas.

In 2012 the South African War Memorial in Richmond was awarded a ‘Grade II’ status and was added to the List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest. However, still, no South Africans in authority were even aware of its existence. To that point, the last parade held at the memorial had taken place there more than 70 years ago.

Tom Mason, a member of The South African Legion in the United Kingdom, came across this memorial whilst members of the CWGC were cleaning it. The history of it pricked Tom’s interest and he brought it back to the South African Legion.

In quick time the South African Legion U.K. arranged a rededication service for the memorial and notified General Andersen of the SANDF of the monuments existence. The monument is now proudly again listed on South Africa’s official war memorials as outlined by the SANDF. The monument is now also the central location for annual South African Pilgrimages as well as regular South African memorial parades in London. The South African Legion’s emblem was proudly unveiled at a centenary parade in the Richmond Cemetary Chapel in thanks to renewed interest in the site.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

By May 2015 the Royal British Legion – South African branch also brought the site to the attention of the RBL. The RBL SA Branch standard was officially dedicated in a ceremony held at the Richmond Cemetary Chapel and South African War Memorial Cenotaph next to it – the dedication took place with numerous branches of the RBL and other veteran organisations in attendance. This South African RBL standard now proudly carries three scrolls on it – it has twice won ‘The Churchill Cup’ as a branch for dedication, growth and reputation and it took part in GP 90 in 2018 and carries the ‘Ypres 2018’ scroll.

Throwing out a significant life-line

By November 2015, a large South African Legion veteran contingent of 40 odd veterans found themselves on parade at Whitehall during the Remembrance Sunday Cenotaph parade, the HMS RBL bravely toeing the South Africans along. However a bigger challenge was looming – much bigger, and it would be the Royal British Legion to the rescue again – not just for South African Legion veterans in the U.K, but for all South African veteran organisations and formations in South Africa itself – and it took place in France.

By November 2015, a large South African Legion veteran contingent of 40 odd veterans found themselves on parade at Whitehall during the Remembrance Sunday Cenotaph parade, the HMS RBL bravely toeing the South Africans along. However a bigger challenge was looming – much bigger, and it would be the Royal British Legion to the rescue again – not just for South African Legion veterans in the U.K, but for all South African veteran organisations and formations in South Africa itself – and it took place in France.

In the beginning of 2016 arrangements in South Africa were going on swimmingly for the marking of the centenary and the extensive South African sacrifice in The Battle of Delville Wood in France in July 1916. An entire South African pilgrimage had been arranged for this centenary event in France – consisting of family members, high school students, all South Africa’s regimental and armed forces associations which fall under the banner of the SA Council of Military Veteran Organisations and all veteran associations – including the South African Legion and Memorable Order of Tin Hats – leave, flights, hotels and busses – all booked.

Then step in the former South African President Jacob Zuma, who decided that the Centenary commemoration date of the Battle of Delville Wood itself did not suite his travel plans. So he changed it, with a couple of months to go ,then he ordered the military and high commission to toe his line, closed the site to his date only and threw everyone else’s plans out the window.

The long and short, it was impossible to move the entire South African pilgrimage to the Somme and The Battle of Delville Wood for the Centenary to suit the President’s new date. Help was needed for the hundreds of South Africans which were going to be stranded on the Somme with no commemoration to attend – and it came from The Royal British Legion working in conjunction with the Royal British Legion’s South African Branch, The South African Legion and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to use of the Thiepval Memorial on the Somme in France as an alternate venue.

2016 Delville Wood and Battle of the Somme Centenary Parade and Pilgrims – Thiepval memorial – France

In this way all The South African pilgrims in France could celebrate the centenary of the full commitment and sacrifice of South Africans to the Somme offensive including, but not exclusive to Delville Wood.

Thiepval was also relevant, although it’s the ‘British’ go-to memorial on the Somme it is also a South African memorial – the official designation of Thiepval is the “Memorial to the 72, 195 British and South African servicemen, who died in the Battle of the Somme of the First World War between 1915 – 1918, with no known grave”. The Thiepval Memorial records the names of 858 South Africans lost during the Somme offensive – including all the ‘missing’ from The Battle of Delville Wood.

The Royal British Legion (RBL) events division jumped in – keen to assist, and they blocked one of their daily “live broadcast” Somme Parades and dedicated the 10th July to a specific South African day.

The Delville Wood Centenary Remembrance at Thiepval parade went ahead on the proper date – and it went ahead to achieve high acclaim from all South African veteran associations and it marked a great success all round – especially to the family members of South Africans lost on the Somme and to South African High Schools and Youth Organisations attending the Somme centenary – who otherwise would have had nothing at all.

and … ‘across the line’

In 2016 and 2017 the South African Legionnaires continued their representation at the annual Whitehall Cenotaph Parade on Remembrance Sunday. In 2017 the South African Legion also formalised an annual pilgrimage parade at the Richmond South African Cenotaph on ‘Poppy Day’ which is the annual Saturday preceding Remembrance Sunday.

By the time the centenary of the end of World War One came around on the 11th November 2018 (1918-2018) at 11am – the South African Legionnaires were front and forward. Attending the parade in the South African branch lifeboat, which had come through and carried the South African contingent over the line. It had been one heck of journey, along the way the bonds and ties between the two Legion’s had been deepened and secured, the South African veterans had risen to show their true colours of leadership and determination winning both Royal British Legion accolades and respect. The presence of the South Africans now ‘recognised’ and the relationship between the two organisations stronger than ever and growing.

As to the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), a South African veteran order with a root in both countries – the U.K. and S.A. As a combat brotherhood, many South African Legionnaires on the Cenotaph Parade in Whitehall are also members of the order, so too many Legionnaires – most representing their specific shellhole. The MOTH has benefited from the resurgence of the SA Legion in the U.K. as they now have an avenue to present themselves at Legion led South African commemorative parades – such as the Remembrance Parade now held regularly on ‘Poppy Day’ in Richmond at the South African cenotaph located there.

As to the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), a South African veteran order with a root in both countries – the U.K. and S.A. As a combat brotherhood, many South African Legionnaires on the Cenotaph Parade in Whitehall are also members of the order, so too many Legionnaires – most representing their specific shellhole. The MOTH has benefited from the resurgence of the SA Legion in the U.K. as they now have an avenue to present themselves at Legion led South African commemorative parades – such as the Remembrance Parade now held regularly on ‘Poppy Day’ in Richmond at the South African cenotaph located there.

The future looks bright as long as the ‘special relationship’ with the Royal British Legion is kept, trying to swim it alone in a foreign country in the hopes that the British establishment will somehow bend their entire remembrance culture to suite this or that South African idiocracy is a foolish endeavour, and that unfortunately has been proved time and again, and it stood in stark proof to all present at the Centenary Cenotaph Parade in London. A better course is to stand in unity and with singular voice, demonstrating values acceptable to the host – and the Royal British Legion’s South African Branch is the ideal vessel to do this – sink this particular boat and the rest will ultimately all slip away.

South African Legionnaires on the march during the centenary cenotaph parde 11/11/2018

You can see now why a lot was on the shoulders of the South African veteran’s at the Whitehall Cenotaph when that gun signalled the silence during the Armistice Day Centenary Parade, they stood to proud attention as the only South Africans represented there aside from the High Commissioner.

It had been a journey starting a century ago when the guns were silenced on the western front, and it had been a journey to correct half a century of silence as South Africa stood in exclusion.

It had been a journey starting a century ago when the guns were silenced on the western front, and it had been a journey to correct half a century of silence as South Africa stood in exclusion.

Here these veterans finally stood in recognition of South African sacrifice at the very epicentre of the entire Remembrance movement started here one hundred years previously – soundly in memory of those South Africans who ‘did not come home’.

Written by Peter Dickens

Related work:

Delville Wood 100 ‘Springbok Valour’… Somme 100 & the Delville Wood Centenary

Great Pilgrimage 90 South Africa was represented at the Great Pilgrimage 90

Photos of SA Legion courtesy Theo Fernandes and Karen Dickens, colourised photographs copyright Imperial War Museum and DB Colour. Pathe clip ‘South Africa Goes’, YouTube sourced. Legion marching video thanks to Catherine Dow.

On the other hand, in my capacity as President of the South African Legion England branch, I am assured that the South African Legion of Military Veterans, as a charity organisation concerned with Remembrance will continue to remember the fallen of all South African military personnel irrespective of race, gender or historical epoch and irrespective of the views presented by South Africa’s Department of Veterans in the article today.

On the other hand, in my capacity as President of the South African Legion England branch, I am assured that the South African Legion of Military Veterans, as a charity organisation concerned with Remembrance will continue to remember the fallen of all South African military personnel irrespective of race, gender or historical epoch and irrespective of the views presented by South Africa’s Department of Veterans in the article today.

Kevin Ashton, chairman of the Gunners Association Western Cape branch, said the decision was an unfortunate break from tradition and an insult to the families of the deceased.

Kevin Ashton, chairman of the Gunners Association Western Cape branch, said the decision was an unfortunate break from tradition and an insult to the families of the deceased.

The South African Legion’s pilgrimages to the United Kingdom often took place over the Remembrance period in November, this sometimes involved a parade in Portsmouth at the memorial there to the men lost on the SS Mendi. They regularly held a parade at the South African Cenotaph in Richmond London, and annually, on Remembrance Sunday they participated in the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade as guests of The Royal British Legion and laid a wreath. The pilgrimages were almost always linked up with visits to Delville Wood in France and Menin Gate in Belgium.

The South African Legion’s pilgrimages to the United Kingdom often took place over the Remembrance period in November, this sometimes involved a parade in Portsmouth at the memorial there to the men lost on the SS Mendi. They regularly held a parade at the South African Cenotaph in Richmond London, and annually, on Remembrance Sunday they participated in the Whitehall Cenotaph Parade as guests of The Royal British Legion and laid a wreath. The pilgrimages were almost always linked up with visits to Delville Wood in France and Menin Gate in Belgium.

On arrival in the U.K. I tried to make contact with a South African Council of Military Veteran Organisation affiliated SAMVOA equivalent to participate in the London Cenotaph Parade, only to discover that no such organisation existed. I watched the cenotaph parade on telly, gob-smacked to see visiting US Marine veterans on parade and not a South African in sight. Advances to find out the status of MOTH (Memorable Order of Tin Hats) shellholes in the UK were met with disappointment – they had no marketing and were closing down shellholes hand over foot and had even done away with the enshrined regulations behind the order – that is it was a ‘Order’ for ‘Combat/Operational statutory force military veterans’ only. However civilians and veterans alike could now join the MOTH Order in the U.K. on an equal level – a change in enshrined MOTH qualifying criteria done to try to keep the order afloat in the U.K, which in its own odd way also serves to undermine the principles of the order.

On arrival in the U.K. I tried to make contact with a South African Council of Military Veteran Organisation affiliated SAMVOA equivalent to participate in the London Cenotaph Parade, only to discover that no such organisation existed. I watched the cenotaph parade on telly, gob-smacked to see visiting US Marine veterans on parade and not a South African in sight. Advances to find out the status of MOTH (Memorable Order of Tin Hats) shellholes in the UK were met with disappointment – they had no marketing and were closing down shellholes hand over foot and had even done away with the enshrined regulations behind the order – that is it was a ‘Order’ for ‘Combat/Operational statutory force military veterans’ only. However civilians and veterans alike could now join the MOTH Order in the U.K. on an equal level – a change in enshrined MOTH qualifying criteria done to try to keep the order afloat in the U.K, which in its own odd way also serves to undermine the principles of the order. In 2012 I colluded with a fellow South African veteran, Norman Sander, to address the matter, and looking at the history, links and association between The South African Legion and The Royal British Legion we felt a branch of The South African Legion in the United Kingdom was the route to go. Godfrey Giles, the then National President of The South African Legion agreed and a branch materialised in the U.K.

In 2012 I colluded with a fellow South African veteran, Norman Sander, to address the matter, and looking at the history, links and association between The South African Legion and The Royal British Legion we felt a branch of The South African Legion in the United Kingdom was the route to go. Godfrey Giles, the then National President of The South African Legion agreed and a branch materialised in the U.K. Highly annoying, and before it blew up out of proportion, to overcome the problem a solution was presented by The Royal British Legion themselves. Come into the fold as a Royal British Legion branch, advance the relationship and values of The South African Legion and the Royal British Legion as a brother organisations, work up the credibility as veterans after a 50 year absence, create a South African presence at the Cenotaph parade and become ‘Recognised’ from within the establishment itself.

Highly annoying, and before it blew up out of proportion, to overcome the problem a solution was presented by The Royal British Legion themselves. Come into the fold as a Royal British Legion branch, advance the relationship and values of The South African Legion and the Royal British Legion as a brother organisations, work up the credibility as veterans after a 50 year absence, create a South African presence at the Cenotaph parade and become ‘Recognised’ from within the establishment itself.

By November 2015, a large South African Legion veteran contingent of 40 odd veterans found themselves on parade at Whitehall during the Remembrance Sunday Cenotaph parade, the HMS RBL bravely toeing the South Africans along. However a bigger challenge was looming – much bigger, and it would be the Royal British Legion to the rescue again – not just for South African Legion veterans in the U.K, but for all South African veteran organisations and formations in South Africa itself – and it took place in France.

By November 2015, a large South African Legion veteran contingent of 40 odd veterans found themselves on parade at Whitehall during the Remembrance Sunday Cenotaph parade, the HMS RBL bravely toeing the South Africans along. However a bigger challenge was looming – much bigger, and it would be the Royal British Legion to the rescue again – not just for South African Legion veterans in the U.K, but for all South African veteran organisations and formations in South Africa itself – and it took place in France.

As to the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), a South African veteran order with a root in both countries – the U.K. and S.A. As a combat brotherhood, many South African Legionnaires on the Cenotaph Parade in Whitehall are also members of the order, so too many Legionnaires – most representing their specific shellhole. The MOTH has benefited from the resurgence of the SA Legion in the U.K. as they now have an avenue to present themselves at Legion led South African commemorative parades – such as the Remembrance Parade now held regularly on ‘Poppy Day’ in Richmond at the South African cenotaph located there.

As to the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH), a South African veteran order with a root in both countries – the U.K. and S.A. As a combat brotherhood, many South African Legionnaires on the Cenotaph Parade in Whitehall are also members of the order, so too many Legionnaires – most representing their specific shellhole. The MOTH has benefited from the resurgence of the SA Legion in the U.K. as they now have an avenue to present themselves at Legion led South African commemorative parades – such as the Remembrance Parade now held regularly on ‘Poppy Day’ in Richmond at the South African cenotaph located there.

It had been a journey starting a century ago when the guns were silenced on the western front, and it had been a journey to correct half a century of silence as South Africa stood in exclusion.

It had been a journey starting a century ago when the guns were silenced on the western front, and it had been a journey to correct half a century of silence as South Africa stood in exclusion.

On the Wednesday, 8th August 2018, The Royal British Legion recreated its 1928 pilgrimage to World War 1 battlefields for thousands of Legion members (90 years on). Great Pilgrimage 90 (GP90) was the Legion’s biggest membership event in modern history. This Great Pilgrimage ended with in a Remembrance Parade held at the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium. The South African sacrifice was acknowledged and remembered at the Great Pilgrimage by the Royal British Legion – South African Branch who laid a special national wreath on behalf of the South African nation as a whole.

On the Wednesday, 8th August 2018, The Royal British Legion recreated its 1928 pilgrimage to World War 1 battlefields for thousands of Legion members (90 years on). Great Pilgrimage 90 (GP90) was the Legion’s biggest membership event in modern history. This Great Pilgrimage ended with in a Remembrance Parade held at the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium. The South African sacrifice was acknowledged and remembered at the Great Pilgrimage by the Royal British Legion – South African Branch who laid a special national wreath on behalf of the South African nation as a whole.

The South African wreath contained a message which read “we will always remember them” in some of the key languages of South Africa on the message (space permitting) – English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, North Sotho, South Sotho and Siswati.

The South African wreath contained a message which read “we will always remember them” in some of the key languages of South Africa on the message (space permitting) – English, Afrikaans, Zulu, Xhosa, North Sotho, South Sotho and Siswati. For those who did not see it live this video will give you an idea of just how prestigious the parade at Menin Gate was and what a military veteran’s association of magnitude in full colour looks like on parade.

For those who did not see it live this video will give you an idea of just how prestigious the parade at Menin Gate was and what a military veteran’s association of magnitude in full colour looks like on parade. Sleep soft, ye dead,

Sleep soft, ye dead,

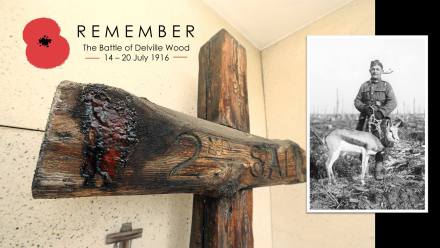

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

In South Africa we have two ‘living memorials’, one for the First World War, the annual running of the Comrades Marathon between Durban and Pietermaritzburg, and another for the Second World War, the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town. Sadly commonly referred to as the Red Cross Children’s Hospital, so not many people know of its wartime origin and its true intention.

In South Africa we have two ‘living memorials’, one for the First World War, the annual running of the Comrades Marathon between Durban and Pietermaritzburg, and another for the Second World War, the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town. Sadly commonly referred to as the Red Cross Children’s Hospital, so not many people know of its wartime origin and its true intention.

At a ceremony held in Cape Town on the 13th February 2018, the Ambassador of France to South Africa, his excellency Christophe Farnaud, bestowed the signet of Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Legion d’Honneur (Knight in the Legion of Honour), France’s highest honour on one of the last surviving South African D Day veterans, General Albert (Albie) Götze.

At a ceremony held in Cape Town on the 13th February 2018, the Ambassador of France to South Africa, his excellency Christophe Farnaud, bestowed the signet of Chevalier de l’Ordre de la Legion d’Honneur (Knight in the Legion of Honour), France’s highest honour on one of the last surviving South African D Day veterans, General Albert (Albie) Götze.

Indeed there had been an administrative oversight and Albie’s LdH application was kick-started again by the South African Legion, and finally Project 71 was able to get a LdH issued by the French Ambassador to the United Kingdom, her excellency Sylvie Bermann.

Indeed there had been an administrative oversight and Albie’s LdH application was kick-started again by the South African Legion, and finally Project 71 was able to get a LdH issued by the French Ambassador to the United Kingdom, her excellency Sylvie Bermann. With an LdH finally in hand, and in South Africa, Philip Weyers from the South African Air Force Association (SAAFA) was contacted to arrange a suitable medal parade for a handover, Philip and SAAFA were also able to engage the French embassy in South Africa, who very keenly agreed to undertake the official presentation to General Götze.

With an LdH finally in hand, and in South Africa, Philip Weyers from the South African Air Force Association (SAAFA) was contacted to arrange a suitable medal parade for a handover, Philip and SAAFA were also able to engage the French embassy in South Africa, who very keenly agreed to undertake the official presentation to General Götze.

The Poppy entered into The Royal British Legion’s history in the same year as the RCEL was formed in Cape Town – 1921, when Madame Guérin promoted what she termed the ‘Inter-Allied Poppy Day’ to the British Legion, a day in which all Britain and her empire who took part in Would War One would remember the fallen with the token of the Flanders red poppy.

The Poppy entered into The Royal British Legion’s history in the same year as the RCEL was formed in Cape Town – 1921, when Madame Guérin promoted what she termed the ‘Inter-Allied Poppy Day’ to the British Legion, a day in which all Britain and her empire who took part in Would War One would remember the fallen with the token of the Flanders red poppy.