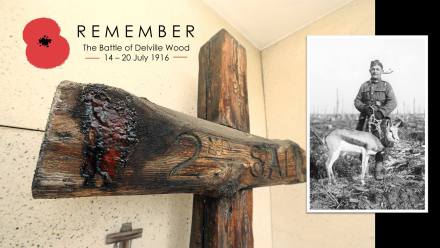

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

There is a poignant and very mystical annual occurrence in South Africa that reminds us every year of the blood sacrifice of South Africans during The Battle of Delville Wood. Every year, in July on the anniversary of the battle itself, a cross made from wood recovered from the shattered tress of the battlefield inexplicably ‘weeps blood’

In Pietermaritzburg there is Christian cross that becomes tacky with red resin just a few days before the anniversary of the massacre of thousands of South African soldiers at the Battle of Delville Wood during the Somme offensive of 1916.

The ‘weeping’ cross has wept these resin “tears” almost every single year, and this phenomenon only coincides with the anniversary of the bloody battle that started it in the first place on July 14, 1916.

The Legend

At the end of World War 1, on return to South Africa, the Commanding officer of the South African Infantry Brigade in France, General Lukin brought back some timber cut from surviving Pinus Sylvester Pine tree (Scots pine) which had grown in abundance at the Delville Wood battleground before much of it was shattered and razed. This wood was to be used to make three crosses to serve as war memorials located in Pietermaritzburg, Cape Town and Durban to commemorate the Battle of Delville Wood (other Christian crosses commemorating the battle are also found in Pretoria at the Union Buildings and Johannesburg and St John’s College). The ‘Pietermaritzburg’ cross is the only one on the three crosses that “weeps” and this phenomenon has baffled experts for years.

The sticky red resin makes its usual annual appearance from a crack near the inscription and knots in the wood on both sides of the crossbar, and over 100 years after the battle, scientists still find it difficult to come up with explanations for the leaking resin.

Known as the “Weeping Cross of Delville”, this cross became a sensation in Natal over many years. The weeping of ‘blood’ came to symbolise the tremendous bloodletting of World War 1 and the Battle of Delville Wood. A legend developed, with people believing that the wood ‘weeps for all the lost soldiers.’ For many years folklore and legend also stated that it would weep until the last survivor of Delville Wood answered the ‘Sunset Call’; however when the last survivor died some years back the cross continued to weep ‘blood’.

The legacy

In the opening weeks of the Somme Offensive in July 1916. On the 14th July 1916 the South African Infantry on the Somme were ordered to protect British troops who had just taken the village of Langueval and hold the adjacent wood about a square mile in size (dubbed ‘devils wood’), and hold it against German attack “at all costs”.

Of the 121 officers and 3,032 men of the South African Brigade who launched the initial attack in the wood, only 29 officers and 751 men eventually walked out only six days later on the 20th July 1916. These men held their objective at a massive cost, even reverting to hand to hand combat to hold the wood when the endless barrages of German artillery file abated – artillery fire rained down on the South African positions at 500 shells/minute razing the wood to just shattered tree stumps (in fact only one original tree survives to this day) – the depth of bravery required to do this under this fire power is simply staggering to contemplate. The losses sustained by the South Africans were one of the greatest sacrifices of the war.

Of the dead and missing, only 142 were given a proper burial and only 77 of those were able to be identified. Most the dead still lie unmarked and unidentified in the wood to this day, exactly where they fell, it is this that makes a visit to Delville wood such a solemn and heart-breaking experience.

Major-General Sir H T Lukin, commanding 5th Division, presenting decorations at the South African Brigade’s memorial service at Delville Wood, 17 February 1918.

Pietermaritzburg’s cross originally stood at the intersection of Durban and Alexandra Roads but was seen to be a traffic hazard and was moved to the Natal Carbineers Garden. In July 1956 it was moved to the MOTH Remembrance Garden in Pietermaritzburg, where it has been ever since. The Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH) ‘Allan Wilson’ shell-hole oversees its good keeping in conjunction with The South African Legion’s Pietermaritzburg branch.

In terms of the two other Delville Wood crosses, one is located at the Union Buildings in Pretoria and the other is located at The Castle in Cape Town, as said – neither of them “weep”.

Some explanations

Some explanations have been offered for the mysterious ‘weeping’ of the Pietermaritzburg Delville Wood Cross, Chemists who analysed samples of the substance in the past found traces of lower linseed oil fragments and pine resin. This was expected as the carpenter, William Olive, soaked the cross in linseed oil before he worked on it. However, the phenomenon baffles forestry experts as it is unusual for wood to continue producing resin for such a long time – especially considering it has now been doing this for over 100 years.

What adds significantly to the mystery of the weeping cross is that Pietermaritzburg’s cross is the only one of the three that weeps at this exact time every year.

Also adding to the mystery is the fact that existing Pine trees in France ooze this resin during the heat of summer, while the cross situated in Pietermaritzburg does so only in winter and specifically over the period of the anniversary of the Delville Wood battle.

“Devil’s Trench” in Delville Wood on the Somme battlefield photographed on 3 July 1917, a year after the fighting.

One suggestion offers the opposite to the ‘expansion’ only experienced by the Pine in France in summer-time and puts forward that is the dry, cold weather experienced around Pietermaritzburg in winter-time, which would cause the wood to shrink and hence forces the resin out.

However, all these suggestions aside, experts like Dr Ashley Nicholas from the school of Biology at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville campus have maintained that it still remains an absolute scientific mystery and all theories put forward to date are sheer guess-work. His position has also been backed up by the Forestry Department’s scientific research council who maintain that no one has yet been able to provide concrete insight into it.

In Conclusion

As long as the legend of the weeping cross continues, it will continue to keep us mindful of the sacrifice at Delville Wood, and the forge it stamped on our young nation’s identity as a ‘South African’ one in 1916. When it will stop nobody knows, and here is where the cross’ current caretakers i.e. the war veterans in the Memorable Order of Tin Hats (MOTH) and South African Legion of Military Veterans (SA Legion) are possibly right – perhaps it will only stop ‘weeping’ when true peace is found and all wars end.

Chairperson of the Pietermaritzburg branch of the SA Legion Peter Willson (right) and vice chairperson Dean Arnold view the refurbished Garden of Remembrance that houses the Delville Wood weeping cross.

Related links and work

Springbok Valour – Battle of Delville Wood Centenary ‘Springbok Valour’… Somme 100 & the Delville Wood Centenary

In Flanders Fields (Afrikaans) ‘In Flanders Fields’ translated into Afrikaans for the Somme 100 commemoration, July 2016

William Faulds VC Taking gallantry at Delville Wood to a whole new level; William Faulds VC MC

A Diary from Delville Wood A South African soldier’s diary captures the horror of Delville Wood

Mascots at Delville Wood: Nancy the Springbok Nancy the Springbok

Mascots at Delville Wood: Jackie the Baboon Jackie; The South African Baboon soldier of World War One

The Battle of Delville Wood 500 shells/min fell on the Springboks … “the bloodiest battle hell of 1916”

Researched by Peter Dickens.

Reference Maritzburg Sun, The Witness – Kwa Zulu Natal. Image copyrights – The Witness and The Imperial War Museum.

This South African’s Victoria Cross turns 100 on the 21/22 March 2018, so today we honour another true South African hero and Victoria Cross recipient, and this man, Captain Reginald Frederick Johnson Hayward VC MC & Bar is one very extraordinary South African.

This South African’s Victoria Cross turns 100 on the 21/22 March 2018, so today we honour another true South African hero and Victoria Cross recipient, and this man, Captain Reginald Frederick Johnson Hayward VC MC & Bar is one very extraordinary South African.

CITATION

CITATION

Reginald worked at the British Broadcasting Corporations (BBC) Publications Department from 1947 to 1952 and as games manager of the Hurlingham Club from 1952 to 1967.

Reginald worked at the British Broadcasting Corporations (BBC) Publications Department from 1947 to 1952 and as games manager of the Hurlingham Club from 1952 to 1967.

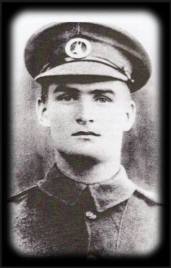

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was scho

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was scho

“On behalf of The Royal British Legion South African Branch I would also like to welcome all here today, it is our privilege to honour the South African sacrifice during the Somme offensive – especially at Delville Wood just a short distance from this memorial.

“On behalf of The Royal British Legion South African Branch I would also like to welcome all here today, it is our privilege to honour the South African sacrifice during the Somme offensive – especially at Delville Wood just a short distance from this memorial.

I would like, if I may, to talk about why is the Battle of the Somme, something that occurred 100 years ago, is so important to us as veterans?

I would like, if I may, to talk about why is the Battle of the Somme, something that occurred 100 years ago, is so important to us as veterans?