Charles Groves Wright Anderson VC, MC (12 February 1897 – 11 November 1988) was a South African born soldier and Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross ‘For Valour’. This is one very brave individual who received a Military Cross in the East African campaign during World War 1, and he went to receive a Victoria Cross in the Malaysian campaign fighting against the Japanese as an Australian in World War 2, During the Malaysian campaign he became a POW and survived Japanese enslavement on the Burma “death” railway.

This is one very remarkable man, read on for his story.

Early Years

Charles Anderson was born on 12 February 1897 in Cape Town South Africa, to Scottish parents. His father, Alfred Gerald Wright Anderson, an auditor and newspaper editor, had been born in England, while his mother, Emma (Maïa) Louise Antoinette, née Trossaert had been born in Belgium. The middle child of five, when Anderson was three the family moved to Kenya, where his father began farming. He attended a local school in Nairobi until 1907, when his parents sent him to England. He lived with family members until 1910, when he was accepted to attend St Brendan’s College in Bristol as a boarder.

The First World War – Kenya and the Military Cross

He remained in England until the outbreak of the First World War. Returning to Kenya, in November 1914, Anderson enlisted as a soldier in the local forces, before later being allocated to the Calcutta Volunteer Battalion as a gunner. On 13 October 1916, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the King’s African Rifles. He fought with the regiment’s 3rd Battalion in the East Africa Campaign against the Askari soldiers of the German Colonial Forces Anderson was awarded the Military Cross for his service in this campaign.

Following the war, having reached the rank of temporary captain, Anderson was demobilised in February 1919 and lived the life of a gentleman farmer in Kenya, marrying Edith Tout, an Australian, in February 1931.

Following the war, having reached the rank of temporary captain, Anderson was demobilised in February 1919 and lived the life of a gentleman farmer in Kenya, marrying Edith Tout, an Australian, in February 1931.

He remained active as a part-time soldier and was promoted to substantive Captain in 1932.

Australia

In 1934, accompanied with his Australian wife, he moved from Kenya to Australia where the couple purchased a grazing property in Australia near Young, New South Wales. In 1939, foreseeing the onset of world war again, he joined the Australian Citizens Military Forces, keeping his commission he was appointed a Captain in the 56 Infantry Battalion.

World War 2

Following the outbreak of the World War 2, Anderson was promoted to the rank of Major. In June 1940, he volunteered for overseas service by joining the Second Australian Imperial Force

By July 1940, Anderson was assigned to the newly formed part of the 22nd Brigade of the 8th Division and deployed to Malaya to reinforce the Australian garrison there against concerns of Japanese military build up.

By July 1940, Anderson was assigned to the newly formed part of the 22nd Brigade of the 8th Division and deployed to Malaya to reinforce the Australian garrison there against concerns of Japanese military build up.

In an odd way Anderson’s experience fighting in East African “Jungles” seemed to qualify him as the right man to tackle fighting in “Malayan Jungles” and he was charged with training troops to treat the jungle as a “friend”. The Japanese used the jungle to their advantage and “Europeans” were up against a steep learning curve to lean “jungle warfare” and put themselves on a equal footing against the Japanese.

He was quite successful at jungle training that just one month later he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and took over as Commanding Officer of the Australian 2/19th Infantry Battalion.

The war in the Pacific began in earnest on 7 December 1941 when Japanese landed on the north-east coast of Malaya and launched thrusts along the western coast of the Malay Peninsula from Thailand. By mid-January, the British Commonwealth forces had retreated to Johore, and the 2/19th was sent into the frontline to support the hard-pressed battalions of ‘Westforce’, an ad hoc formation consisting of Australian and Indian troops.

The Battle of Muar

From 18–22 January 1942 Anderson and his Australian Infantry Battalion took part in The Battle of Muar (fought near the Muar River). Anderson’s force had destroyed ten enemy Japanese tanks, when they were cut off. Anderson led his force through 24 kilometres of enemy-occupied territory to get back to the Allied line at Parit Sulong. During the entire retreat they were repeatedly attacked by Japanese air and ground forces all the way, at times Anderson had to lead bayonet charges and even got into hand-to-hand combat against the Japanese.

Once reaching Parit Sulong, Anderson famously went on the attack against the Japanese which opened the way for the Allies to retreat further to Yong Peng to meet up with the main force heading for Singapore.

However the main bridge at Parit Sulong, had fell into Japanese hands with a Japanese machine gun nest defending the bridge, this blocked his advance and Anderson’s force was eventually surrounded, and a heavy battle then ensued for several days. Allied troops now at Yong Peng attempted to break through the Japanese lines to reinforce Anderson’s men but were unsuccessful in getting to the surrounded men.

Without reinforcements, unable to get across the bridge and heavily outnumbered, Anderson’s Australian and Indian troops were attacked and harassed continuously by Japanese tanks, machine gun, mortar and air attacks and suffered heavy casualties. Yet they held their position for several days and refused to surrender. During the battle, Anderson had tried to evacuate the wounded by using an ambulance, but the Japanese would also not let the ambulance pass the bridge.

Australian and Japanese artworks (left to right respectively) depict the action at Parit Sulong.

The Victoria Cross

Although Anderson’s detachment attempted to fight its way through another 13 kilometres miles of enemy-occupied territory to Yong Peng, this proved impossible, and Anderson had to destroy his equipment and attempted to work his way around the enemy. Anderson then ordered every able man to escape through the jungle to link up with the retreating main force in Yong Peng heading for Singapore. They had no choice but to leave the wounded to be cared for by the enemy, assuming the Japanese would take care of the wounded. But unfortunately, the Japanese unit at Parit Sulong later executed the approximately 150 wounded Australian soldiers and Indian soldiers next to the bridge of Parit Sulong, in what is now knowns as the Parit Sulong Massacre.

After the war, General Takuma Nishimura of the Imperial Japanese Army, was tried and hanged by Australia in relation to the massacre in 1951.

For his brave actions and leadership in Muar and the difficult retreat from Muar to Parit Sulong and the subsequent difficult battle at Parit Sulong led by Anderson, he was awarded the highest and most prestigious decoration for gallantry in the face of the enemy – The Victoria Cross

His VC citation, gazetted on 13 February 1942, states: “…for setting a magnificent example of brave leadership, determination and outstanding courage. He not only showed fighting qualities of very high order but throughout exposed himself to danger without any regard for his own personal safety”.

Anderson got his remaining troop to Singapore, and shortly afterwards he was hospitalised. As the situation became desperate in Singapore, on 13 February, Anderson discharged himself and returned to the heavily-mauled 2/19th, by then down to just 180 men from its authorised strength of 900. He led them until Singapore surrendered to the Japanese two days later.

Lt General Arthur Percival, led by a Japanese officer, walks under a flag of surrender on 15 February 1942, the largest surrender of British led forces in history.

POW and the ‘Death Railway’

Anderson spent the next three harrowing years of the war as a Prisoner of War under the Japanese, and he was subjected to the same grisly fate that nearly all British and Commonwealth soldiers captured at Singapore had to endure.

He was shipped with a the group of 3,000 other Allied POW to Burma and they were used as slave labour to build the 415 km railway link between Nong Pladuk in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma. This is the infamous “Death” railway and “Bridge over the River Kwai” episode of World War 2, a blot on the landscape of humanity.

Throughout his time on the “death railway”, Anderson is noted as working to mitigate the hardships of other prisoners, leading by personal example and maintaining morale.

The construction of the Burma Railway is counted as a war crime over 3,000 POWs died constructing it. After the completion of the railroad, most of the surviving POWs were then transported to Japan.

After the end of the war, 111 Japanese military officials were tried for war crimes because of their brutalization of POWs during the construction of the railway, with 32 of these sentenced to death.

Also at the end of the war, Anderson was liberated and he repatriated back to Australia. His appointment in the army was terminated on 21 December 1945 and he returned to his property in New South Wales.

Later life and Politics

Charles Anderson entered into Australian politics in 1949 winning House Representative for the Division of Hume as a member of the Country Party – twice between 1949 and 1961. A career as a politician he served in parliament as a member of the Joint Committee on the ACT (Australian Central Territory) and also for foreign affairs.

Charles Anderson entered into Australian politics in 1949 winning House Representative for the Division of Hume as a member of the Country Party – twice between 1949 and 1961. A career as a politician he served in parliament as a member of the Joint Committee on the ACT (Australian Central Territory) and also for foreign affairs.

Anderson owned farming properties around Young, New South Wales, and following his retirement from politics in 1961, moved permanently to Red Hill in Canberra, where he died in 1988, aged 91.

He was survived by three of his four children. There is a memorial stone and plaque for Anderson at Norwood Crematorium, Australian Capital Territory.

Anderson’s medal set, note Victoria Cross and the Military Cross followed by his “Pip, Squeak and Wilfred” WW1 medal set and WW2 medals which follow them including the Pacific Star.

Source: Wikipedia and the Australian War Memorial

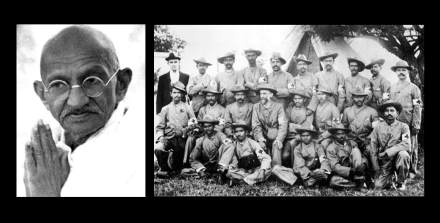

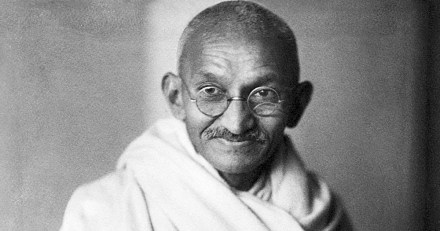

In this context rose a young, British educated lawyer – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who emigrated to the British Colonies in Southern Africa to make a name for himself and start a new life. He was at the start of his life quite supportive of British policies in South Africa and those of British empire and expansion.

In this context rose a young, British educated lawyer – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who emigrated to the British Colonies in Southern Africa to make a name for himself and start a new life. He was at the start of his life quite supportive of British policies in South Africa and those of British empire and expansion.

“My first meeting with Mr. M. Gandhi was under strange circumstances. It was on the road from Spion Kop, after the fateful retirement of the British troops in January 1900.

“My first meeting with Mr. M. Gandhi was under strange circumstances. It was on the road from Spion Kop, after the fateful retirement of the British troops in January 1900.

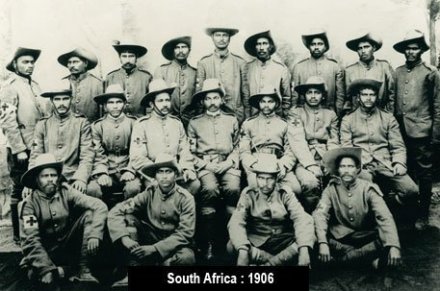

The Zulu uprising in Natal during 1906 was the result of a series of culminating factors and misfortunes; an economic slump following the end of the Boer War, simmering discontent at the influx of White and Indian immigration causing demographic changes in the landscape, a devastating outbreaks of rinderpest among cattle and a rise in a quasi-religious separatist movement with a rallying call of ‘Africa for the Africans’.

The Zulu uprising in Natal during 1906 was the result of a series of culminating factors and misfortunes; an economic slump following the end of the Boer War, simmering discontent at the influx of White and Indian immigration causing demographic changes in the landscape, a devastating outbreaks of rinderpest among cattle and a rise in a quasi-religious separatist movement with a rallying call of ‘Africa for the Africans’.

The 21,516-ton RMS Empress of Canada, was a liner of the Canadian Pacific Steam Ship Company, which had been converted to a troop transport. To the German U-boat captains she managed to elude for three and a half years, she was known as “The Phantom”.

The 21,516-ton RMS Empress of Canada, was a liner of the Canadian Pacific Steam Ship Company, which had been converted to a troop transport. To the German U-boat captains she managed to elude for three and a half years, she was known as “The Phantom”. After 29 days the UK authorities assumed that the Lulworth Hill had been lost with all hands and duly informed their families.On 7 May the HMS Rapid picked up the Lulworth Hill’s liferafts. Of the 14 men that had survived the sinking, after 50 days adrift only two, Seaman Shipwright (i.e. carpenter) Kenneth Cooke and Able Seaman Colin Armitage, remained alive.

After 29 days the UK authorities assumed that the Lulworth Hill had been lost with all hands and duly informed their families.On 7 May the HMS Rapid picked up the Lulworth Hill’s liferafts. Of the 14 men that had survived the sinking, after 50 days adrift only two, Seaman Shipwright (i.e. carpenter) Kenneth Cooke and Able Seaman Colin Armitage, remained alive.

Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia was a massive loss to the Italian war effort and the Italian Navy, he was posthumously awarded the Knight’s Iron Cross from Germany and the Gold Medal for Military Valor by King Vittorio Emanuele III. Rather unusually given the outcome of the war, as testament of this legacy, two modern Italian Sauro-class submarines are named:

Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia was a massive loss to the Italian war effort and the Italian Navy, he was posthumously awarded the Knight’s Iron Cross from Germany and the Gold Medal for Military Valor by King Vittorio Emanuele III. Rather unusually given the outcome of the war, as testament of this legacy, two modern Italian Sauro-class submarines are named:

Winning a Victoria Cross for gallantry and surviving the ordeal has some luck associated to it, and this lucky charm of a VC winner is testament of this. Every Anzac Day we recall the Gallipoli campaign, and we remember the heroes of the campaign – Australian, New Zealand, British and even in modern times the Turkish heroes too.

Winning a Victoria Cross for gallantry and surviving the ordeal has some luck associated to it, and this lucky charm of a VC winner is testament of this. Every Anzac Day we recall the Gallipoli campaign, and we remember the heroes of the campaign – Australian, New Zealand, British and even in modern times the Turkish heroes too. By the 4th March 1911 he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. He rose to the rank of Captain and by the summer of 1915 he was with his Regiment landing on the shores of Gallipoli. Carrying a lucky charm into battle (see featured image), It would be here that he would earn his Victoria Cross.

By the 4th March 1911 he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 6th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. He rose to the rank of Captain and by the summer of 1915 he was with his Regiment landing on the shores of Gallipoli. Carrying a lucky charm into battle (see featured image), It would be here that he would earn his Victoria Cross.

“For conspicuous gallantry at Suvla Bay on 9th September, 1915. He made a reconnaissance of the coast, stripping himself and carrying only a revolver and a blanket for disguise. He swam and scrambled over rocks, which severely cut and bruised him, and obtained some valuable information and located a gun which was causing much damage. The undertaking was hazardous. On one occasion he met a patrol of 12 Turks who did not see him, and later a single Turk whom he lulled. He returned to our lines in a state of great exhaustion”.

“For conspicuous gallantry at Suvla Bay on 9th September, 1915. He made a reconnaissance of the coast, stripping himself and carrying only a revolver and a blanket for disguise. He swam and scrambled over rocks, which severely cut and bruised him, and obtained some valuable information and located a gun which was causing much damage. The undertaking was hazardous. On one occasion he met a patrol of 12 Turks who did not see him, and later a single Turk whom he lulled. He returned to our lines in a state of great exhaustion”.

South African. The South Army (and Air Force) was issued with a “Polo” style “Pith” helmet. Made from cork it was not intended to protect the head from flying bullets and shrapnel, that was the purpose of the British Mk 2 Brodie helmet (also issued to South Africans). The pith helmet was worn mainly as sun protection when not in combat.

South African. The South Army (and Air Force) was issued with a “Polo” style “Pith” helmet. Made from cork it was not intended to protect the head from flying bullets and shrapnel, that was the purpose of the British Mk 2 Brodie helmet (also issued to South Africans). The pith helmet was worn mainly as sun protection when not in combat. Australia. The Australian army wore the “slouch hat”, also intended for sun protection when not in combat, like the South Africans they where issued with the British “Brodie” Mk2 steel helmet when in combat.

Australia. The Australian army wore the “slouch hat”, also intended for sun protection when not in combat, like the South Africans they where issued with the British “Brodie” Mk2 steel helmet when in combat. In addition to Australians, believe it or not some South African units also wore the “slouch hat”. Most notable was the South African Native Military Corps members, who made up about 48% of the South African standing army albeit in non frontline combat roles during both WW1 and WW2. The legacy of the “slouch” in the modern South African National Defence Force is however now on the decline and little remains now of its use, a pity as it would be a gracious nod to the very large “black” community contribution to both WW1 and WW2.

In addition to Australians, believe it or not some South African units also wore the “slouch hat”. Most notable was the South African Native Military Corps members, who made up about 48% of the South African standing army albeit in non frontline combat roles during both WW1 and WW2. The legacy of the “slouch” in the modern South African National Defence Force is however now on the decline and little remains now of its use, a pity as it would be a gracious nod to the very large “black” community contribution to both WW1 and WW2. In an iconic Australian War Memorial photograph to demonstrate this unique association, a Australian soldier working on the Beirut-Tripoli railway link is seen here chatting with two members of a South African Pioneer Unit (SA Native Military Corps) also working on the railway. The photo is designed to show off their similarities of dress and bearing and promote mutual purpose.

In an iconic Australian War Memorial photograph to demonstrate this unique association, a Australian soldier working on the Beirut-Tripoli railway link is seen here chatting with two members of a South African Pioneer Unit (SA Native Military Corps) also working on the railway. The photo is designed to show off their similarities of dress and bearing and promote mutual purpose. Interestingly the gun in the pit is not South African standard issue. Instead it is a British made Hotchkiss Portative MK 1, which was used by the Australians, dating back to World War 1, so it is probably their gun pit. Of French design the MK I was a .303 caliber machine gun, used in ‘cavalry/infantry’ configuration, with removable steel buttstock and a light tripod. This gun is normally fed from either flexible “belts” or strips like you see in the featured image. Normal Hotchkiss Portative strips hold 30 rounds each.

Interestingly the gun in the pit is not South African standard issue. Instead it is a British made Hotchkiss Portative MK 1, which was used by the Australians, dating back to World War 1, so it is probably their gun pit. Of French design the MK I was a .303 caliber machine gun, used in ‘cavalry/infantry’ configuration, with removable steel buttstock and a light tripod. This gun is normally fed from either flexible “belts” or strips like you see in the featured image. Normal Hotchkiss Portative strips hold 30 rounds each.

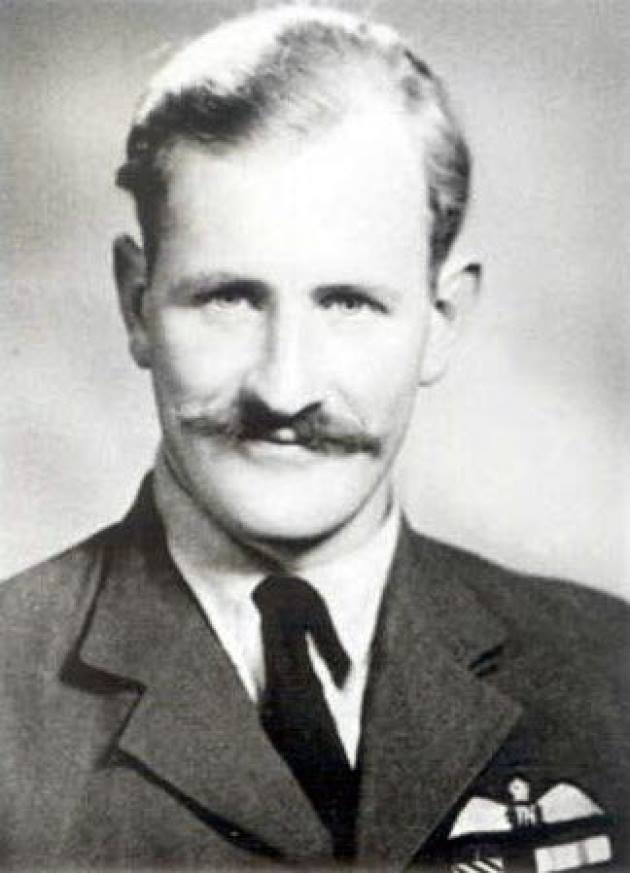

In 1938 Frederick moved to Great Britain and joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) on a short service commission as part of the Empire Flying Training Wing.

In 1938 Frederick moved to Great Britain and joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) on a short service commission as part of the Empire Flying Training Wing.

Oberleutnant Gerhard Homuth was one of the top scoring German Luftwaffe aces in the Second World War. He scored all but two of his 63 victories against the Western Allies whilst flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109, especially in North Africa, he was later promoted to the rank of Major. He was last seen on 2 August 1943 in a dogfight with Soviet fighters in the Northern sector – Eastern Front whilst flying a Focke Wulf 190A. His exact fate remains unknown.

Oberleutnant Gerhard Homuth was one of the top scoring German Luftwaffe aces in the Second World War. He scored all but two of his 63 victories against the Western Allies whilst flying the Messerschmitt Bf 109, especially in North Africa, he was later promoted to the rank of Major. He was last seen on 2 August 1943 in a dogfight with Soviet fighters in the Northern sector – Eastern Front whilst flying a Focke Wulf 190A. His exact fate remains unknown.

“Tall, blond and sporting a splendid handlebar moustache, Stapleton was the epitome of the dashing fighter pilot. As the Battle of Britain opened in July 1940, he was flying Spitfires with No 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron and saw action off the east coast of Scotland. He shared in the destruction of two German bombers before his squadron moved to Hornchurch in late August as the Battle intensified.

“Tall, blond and sporting a splendid handlebar moustache, Stapleton was the epitome of the dashing fighter pilot. As the Battle of Britain opened in July 1940, he was flying Spitfires with No 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron and saw action off the east coast of Scotland. He shared in the destruction of two German bombers before his squadron moved to Hornchurch in late August as the Battle intensified.

To many people Stapleton was one of the real “characters” to survive the war. His favourite aircraft was the Spitfire, and when a colleague described it as “beautiful and frail, yet agile, potent and powerful” Stapleton responded: “I always wanted a lady like that.”

To many people Stapleton was one of the real “characters” to survive the war. His favourite aircraft was the Spitfire, and when a colleague described it as “beautiful and frail, yet agile, potent and powerful” Stapleton responded: “I always wanted a lady like that.”