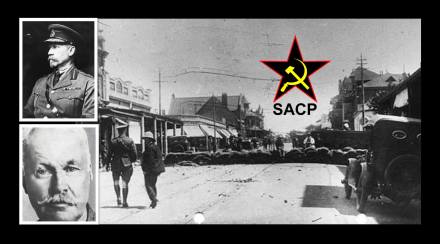

The narrative that many South Africans understand of The Rand Revolt today is one linked to Jan Smuts, sending tanks and aeroplanes to brutally repress a miners strike murdering his own kind – white South Africans, and it is a narrative his opposition, the National Party, used repeatedly to criticise Smuts for political expediency for decades.

The Nationalists went further, as during the Apartheid period Smuts was painted as traitor to his own ‘Volk’ (people) partly because of the actions he took to quell this ‘miners strike’ and adding to this was the example of Jopie Fourie and the ‘1914 Afrikaner Revolt,’ both of which proved beyond doubt Smuts’ betrayal and brutality to his own kind, certainly according to the Nationalists.

However, like any history derived for political expediency, much of this above narrative is very incorrect. The truth is the Rand Revolt was much more than a simple miners strike and a deep irony sits behind the old Nationalists claims of Smuts’ betrayal – as the nationalists had found sympathy using their traditional enemies – the Communists – in order to gain political points. It is the strangest of bedfellows on which to press a criticism. The truth is The Rand Revolt was South Africa’s first ‘Communist Revolution’ and the rebels (not just strikers) were not Afrikaner Boere ‘Volk’, they were, for the most part, led by a bunch of very militant English Communists with origins in Great Britain.

These Communist miners were joined by the ‘Syndicalists’ in their upcoming fight to overthrow the South African Union government, the Syndicalists were a similar organisation to the Communists as they held the same view – that an economic system should exist where the worker ‘syndicate’ owns the mine, not the capitalist.

These miners were in fact the same miners who provided the British with the trigger to start the Boer War, the same ‘British’ miners who repeatedly protested for their workers rights to the old Transvaal Government, and even then Paul Kruger sent in his infamous ‘ZAR’ Policemen to baton and break up these miners’ strikes and protests on the Rand.

They were also the rational behind the Jameson Raid. Leander Starr Jameson and his colleagues on the mines in Johannesburg planned the raid ostensibly to liberate these miners from Transvaal government oppression (coupled of course with Rhodes’ ideals of imperial expansionism). This time the Jameson ‘revolt’ and miners uprising was universally crushed by the Transvaal government (The old South African Republic) who sent in their military Commandos to put an end to it.

The white miners on the Rand and their issues, which almost universally revolved around citizen and worker rights, were a constant thorn in both Boer Republics, they were the reason behind the destruction of the Boer nation by Britain in the 2nd Anglo Boer war, friends of the Afrikaner ‘Boer’ population they were not.

So now that we have dispelled the first miss-truth, let’s have a look at what this revolt was really all about and ask ourselves if Smuts had any alternative to the course he took. Also lets hypothetically challenge whether the Rand Revolt of 1922 would have been handled any differently by the old Transvaal government (should the Boer War not have happened) and the Nationalist government (should they have been in power at the time of the revolt instead of Smuts).

Origins of a Communist Rebellion in South Africa

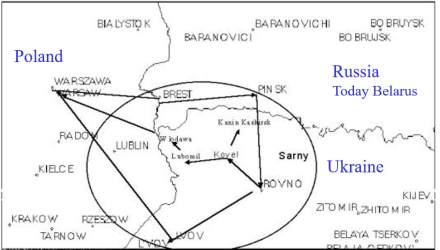

The Rand Rebellion (also known as the Rand Revolt or Second Rand Revolt – the Jameson Raid was the first) was an armed uprising of white miners on the Witwatersrand mining belt in March 1922.

The Rand Rebellion (also known as the Rand Revolt or Second Rand Revolt – the Jameson Raid was the first) was an armed uprising of white miners on the Witwatersrand mining belt in March 1922.

The trigger was a drop in the world price of gold from 130 shillings (£6 10s) a fine troy ounce in 1919 to 95s/oz (£4 15s) in December 1921, the companies tried to cut their operating costs by decreasing wages, and by weakening the colour bar to enable the promotion of cheaper black miners to skilled and supervisory positions.

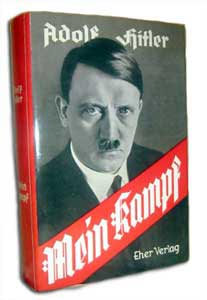

This in turn triggered a strike action led by the South African Communist Party which very quickly turned into an open armed rebellion against the state. The Communist Party in South Africa in fact took a very proactive role in transcending a simple strike to an open armed revolt, they based their argument on the ‘class struggle’ premise and sought to follow the lead of the Russian Communist workers revolution in 1917 which saw the overthrow of the Tzar by the Bolsheviks and the establishment of Soviet Russia.

Consider that by 1922 this revolution in Russia had only occurred 5 years perviously. Buoyed by the success of the Russian communists, the South African Communists hoped that their action in Africa would force regime change in the Transvaal and furthermore inspire more Communist overthrows of state by other worker colonies in far-flung countries like Australia and India.

Consider the summary of the Revolt given by David Ivon Jones – a mine-union communist and you’ll see the point:

The Rand Revolt was ‘the deed of indictment against capitalism [which was] filling up from every land and every clime; and the roll of honour of proletarian heroism [was] growing from Africa, Australia and India . . . ‘

The South African Communist Party’s racist beginnings

However, contrary to current views of The South African Communist Party (SACP), the SACP has as its origin an ‘Apartheid’ beginning, it was initially not the party for Black Africans, in fact by the time of the Rand Revolt it had a pretty strong ‘whites only’ philosophy underpinning it.

‘Comrade Bill’ Andrews

It was founded by William (Bill) Henry Andrews who became the first Chairman of the SACP. Bill Andrews was born in England and by 1890 he had travelled to South Africa to work on the mines, here he became a predominant trade union organiser.

A fighter for the rights of ″white″ labour, Bill Andrews was always quick to complain when he perceived that an African (whom he openly called ″Kaffirs″) might take away a job from a white man.

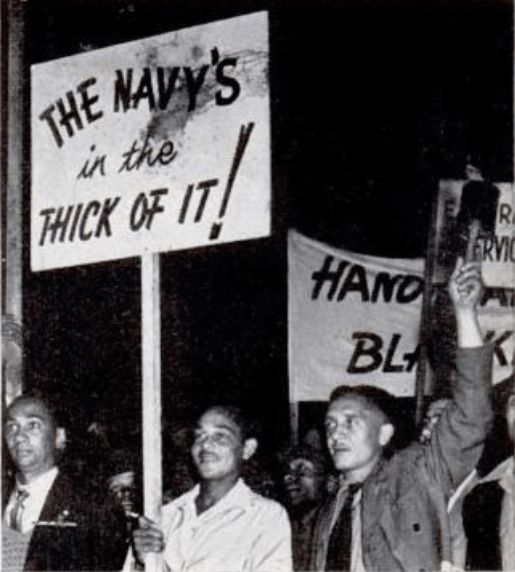

By 1922 Bill Andrews was the first General Secretary of the South African Communist Party, and as a result the SACP approached the Rand Rebellion as a fight for white worker rights and white worker job reservation. In fact they used the slogan”Workers of the world, unite and fight for a white South Africa!” as a rally call to their Communist brethren all over the world to join them.

To anyone who is wondering at this stage why the modern African National Congress (ANC) politicians when in conflict with the modern South African Communist Party (SACP) politicians feely call them ‘racists’, now you know the reason why.

The Rand Revolt background

In the early days of mining no Africans possessed the skills necessary for deep level mining, therefore the division of the work force had been between white miners and white management. The custom that skilled work was done by white men had been reinforced by legislation when Chinese labourers were introduced. During World War I the overall ratio of white to black workers had been maintained. As time passed, however, black miners began to acquire these skills, although their wages remained at very low rates. In September 1918, white mine workers had succeeded in persuading the Chamber of Mines to agree that no position filled by a white worker should be given to an African or Coloured worker.

When the Chamber of Mines gave notice that it would be abandoning the agreement and would be replacing 2,000 semi-skilled white men with cheap black labour, the white miners reacted strongly. Their jobs and pay packets were threatened by the removal of the colour bar, and they feared the social encroachment on their lives that differences in colour, standards of living, and the cultural background of the coloured races might make. Sporadic strikes were launched in 1921, but these did not become widespread until the end of the year.

The trade unions

Because of the large number of mines and workingmen living in and around Fordsburg, Johannesburg, trade unions had become active in this area. This set the scene for the revolt in Fordsburg. At this time some trade union members were attracted to the spirit of socialism and others became communists, who referred to themselves as ‘Reds’. The leader of the Communist Party, Bill Andrews, known to his chums as ‘Comrade Bill’, urged a general strike. In the meanwhile, a group of revolutionaries organized commandos under the leadership of people who called themselves the ‘Federation of Labour.’

Strikes

The New Year marked a strike on the collieries of the Transvaal. Strikes soon spread to the gold mines of the Reef, especially those in the East Rand, when electrical power workers and those in engineering and foundry occupations followed suit. By January 10, stoppage of work in mining and allied trades was complete. Bob Waterston, Labour Party MP, sponsored a resolution urging that a provisional government declare a South Africa republic. Tielman Roos, leader of the National Party in the Transvaal, submitted this proposal to a conference of MPs convened in Pretoria, but they rejected it outright. Roos himself was emphatic that the National Party would have nothing to do with a revolt.

The revolt itself

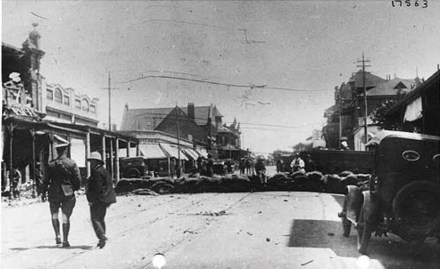

In February 1922, the protracted negotiations with the South African Industrial Federation broke down when the Action Group seized control, armed some white miners, and set up barricades. Mob violence spread alarmingly with bands of white men shooting and bludgeoning unoffending Africans and coloured men ‘as though they were on a rat hunt’. A general strike was proclaimed on Monday, 6 March and on Wednesday, the strike turned into open revolution in a bid to capture the city.

On 8 March, white workers attempted to take over the Johannesburg post office and the power station, but they met with stout resistance from the police, and the day ended in fights between white strikers and black miners. The Red commandos made the most of this chaos by encouraging their rebel followers to obtain firearms and other weapons from white miners and their sympathizers under the pretext of trying to protect women and children from attacking blacks. By spreading the alarm, they discovered who had firearms and immediately confiscated them. The following day six units of the Active Citizen Force were called out to prevent further disorder.

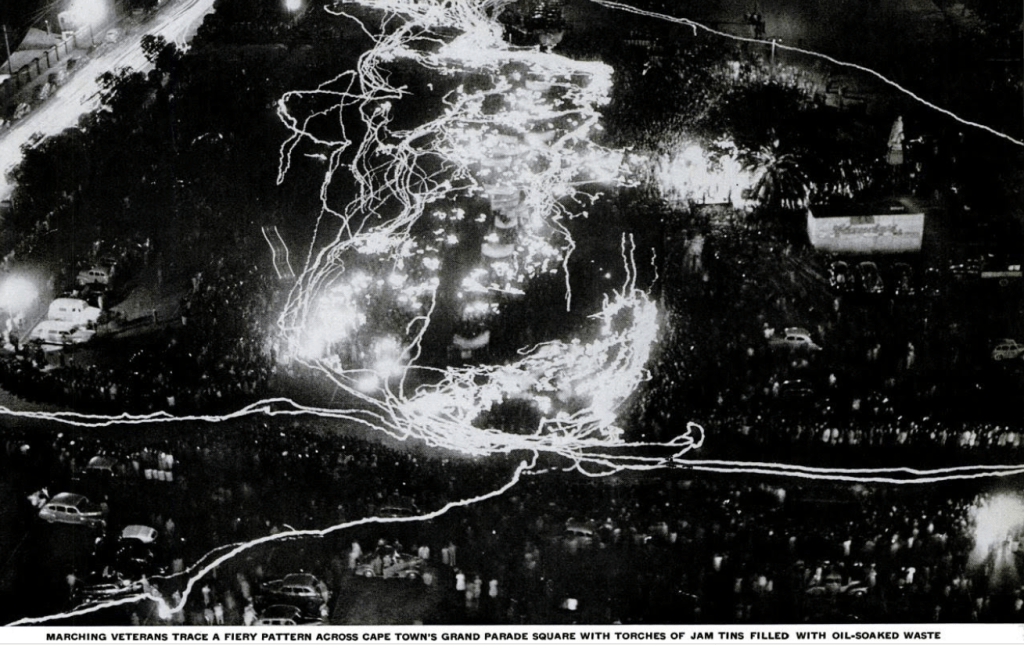

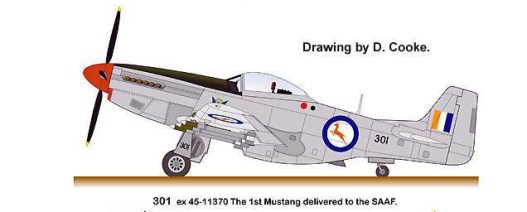

On Friday, 10 March, a series of explosions signalled the advance of the Red commandos and an orgy of violence began. To quell this the Union Defence Force was called out, as well as the aircraft of the fledgling SAAF and the artillery. By this time, Brakpan was already in the hands of the rebels, and pitched battles were raging between the strikers and the police for control of Benoni and Springs. Aeroplanes strafed rebels and bombed the Workers’ Hall at Benoni. Rebels besieged the Brakpan and Benoni police garrisons. At Brixton 1,500 rebels surrounded 183 policemen and besieged them for 48 hours. From the air, pilots observed the plight of the beleaguered Brixton policemen. Swooping over them, they dropped supplies, and then returned to bomb the rebels. During one of these sorties Colonel Sir Pierre van Ryneveld’s observer, Captain Carey Thomas, was shot through the heart.

Martial law was proclaimed and burgher commandos were called up from the surrounding districts. On Saturday, 11 March, the Reds attacked a small detachment of the Imperial Light Horse at Ellis Park in Doornfontein, which sustained serious losses, and, on their way to the East Rand, the Transvaal Scottish marched into an ambush at Dunswart, sustaining heavy losses. The rebels searched citizens passing through Jeppestown and Fordsburg and sniped at those they thought were supporters of the mine management, as well as many policemen on duty in the streets. Prime Minister General Jan Smuts was widely blamed for letting the situation get out of hand. He arrived on the Rand at midnight to take charge of the situation.

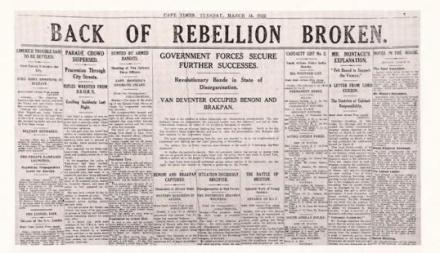

The rebellion is crushed

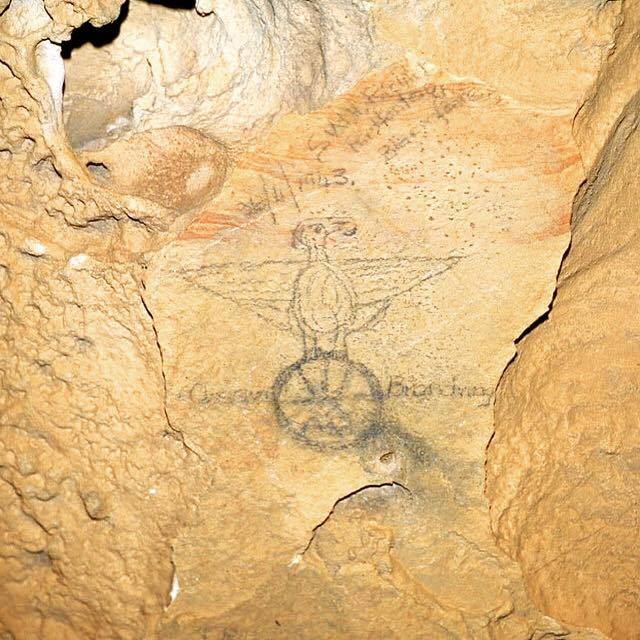

On Sunday, 12 March, military forces and citizens attacked the rebels holding out on the Brixton ridge and took 2,200 prisoners. The next day government troops led by General van Deventer relieved the besieged police garrisons in Brakpan and Benoni. On 15 March, the artillery bombarded the strikers’ stronghold at Fordsburg Square and in the afternoon, it fell to the government. Before committing suicide in this building, the two communist leaders, Fisher and Spendiff, left a joint note: ‘We died for what we believed in – the Cause’. Samuel Alfred (Taffy) Long, heralded by subsequent labour histories as one of South Africa’s greatest working-class martyrs, was arrested after the defeat of Fordsburg. He was charged with murder and later also with high treason and the possession of loot.

From 15 to 19 March 1922, government troops cleared areas of snipers and did house-to-house searches of premises belonging to the Reds, making many arrests. On March 16, the Union Defence Headquarters issued a press statement that the revolt had been a social revolution organized by Bolshevists, international socialists and communists. The revolt was declared over from midnight on 18 March.

Aftermath and resultant changes in goverment and law

In all the Rand Revolt was a calamity. It cost many lives and millions of pounds. About 200 people were killed – including many policemen, and more than 1,000 people were injured. Fifteen thousand men were put out of work and gold production slumped. In the aftermath, some of the rebels were deported and a few were executed for deeds that amounted to murder. John Garsworthy, leader of the Brakpan commando, was sentenced to death, but he was later reprieved. Four of the leaders were condemned to death and went to the gallows singing their anthem, ‘The Red Flag’.

The Red Flag anthem was the rally anthem for British Communists – and as an aside it is still the official song for the British Labour Party and sung at their annual party rally.

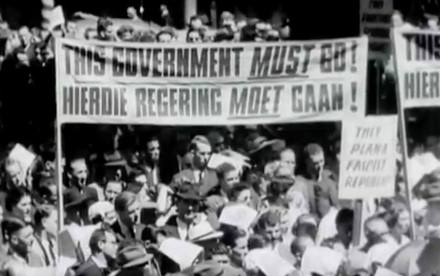

Smuts was widely criticised for his severe handling of the revolt. He lost support and was defeated in the 1924 general election. This gave Hertzog’s Nationalist Party and the Labour Party, supported by white urban workers, the opportunity to form a pact (the old adage ‘enemy of my enemy is my friend’ applied – a strange and uneasy pact indeed).

JBM Hertzog

Whilst Smuts stood in opposition, three important Acts were passed by Hertzog’s Nationalists whilst in pact with Labour. They gave increasing employment opportunities to whites and introduced programme of African segregation. The first was the Industrial Conciliation Act of 1924, which set up machinery for consultation between employers’ organisations and trade unions. The second was the Wage Act, which set up a board to recommend minimum wages and conditions of employment. The third was the Mines and Works Amendment Act of 1926, which firmly established the principle of the colour bar in certain mining jobs.

South African Communists U-turn

Two things happened after the 1922 Revolt that would have long reacting ramifications. Firstly Jan Smuts lost the next election and had to sit in the opposition bench and endure coalition Nationalist law making in the Union along race barrier lines for 15 years until 1939, when he finally became Prime Minister of South Africa for a second time.

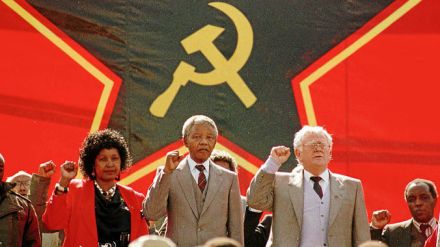

Secondly the South African Communist Party evolved into the political juggernaut it is now, and in a strange twist, the Rand Revolt in 1922 forced the hard-line Communists to re-appraise their views on ‘white’ worker rights. The Rand Revolt showed this to be a weakness and broader population support was needed if there was to be any significant Communist revolt in South Africa to create an independent Republic under communist rule.

So, even though their jobs were now protected by ‘colour bar’ laws, they turned against these hard fought for rights. ‘Comrade Bill’ Andrews was expelled from the South African Communist Party in a series of purges over the their new “black Republic” policy (he was only permitted to rejoin the SACP many years later in 1938 aged 68).

Just six years after the Rand Revolt, by 1928 the SACP agreed with their controlling body ‘Communist International’ to adopt the “Native Republic” thesis which stipulated that South Africa was a country belonging to the Natives i.e. the Blacks. The resolution was influenced by a delegation from South Africa. James la Guma, the new Communist Party Chairperson from Cape Town, he had already met with the leadership of ‘Communist International’ to agree the new way forward.

By 1928, 1,600 of the SACP’s 1,750 members were Black. During this period, the party was accused of dismissing attempts by other multiracial revolutionary organisations (the ANC and Syndicalists) and using revisionist history to claim that the Communist party and its Native Republic policy was the only viable route to African liberation.

By 1929: the party adopted a “strategic line” which held that, “The most direct line of advance to socialism runs through the mass struggle for majority rule”.

The SACP today

Did Smuts have a choice?

Smuts sent in 20 000 troops to crush the Revolt. The fact is, it was a Communist Revolt to establish the Transvaal as a Communist Republic, and not just a simple strike. The Communists wanted the fight, tooled up for the fight and even annexed cities to forward their goal. So the answer in truth is that Smuts did not really have a choice.

Would anyone else have reacted any differently to Smuts?

Jan Smuts

Upfront we established that the old Boere Transvaal Republic had no appetite for these militant miners and their strikes and revolts. Their reaction in quelling them was brutal and swift.

Politically expedient packs between the Communists and the Nationalists after the 1922 Revolt aside, the Nationalists had real no appetite for the Communists – and by 1928 the Communists certainly had no appetite for the Nationalists.

The Nationalists, who by 1948 were in full control of South Africa, had a deep-seated hatred for Communism, they regarded them as the ‘Rooi gevaar’ (Red Danger) and used this as a call to action when embarking South Africa on a war against Communism. This manifested itself in not only the implementation of ‘anti-communist’ legislation and the ‘banning’ of the organisation in 1950, but also in a proxy Cold War against ‘Communism’ fought in Angola and Namibia from 1966 to 1989. Over the two decades of The Border War, the Nationalists killed thousands more ‘communists’ using the country’s defence force. It was certainly a far stronger reaction against Communism than Smuts’ use of the defence force against the Communists in the Rand Revolt.

So to answer the hypothetical question whether the Nationalists would have reacted differently to the Rand Revolt had they been in power instead of Smuts, the answer would in all likelihood be ‘no’, in fact it would be very probable that their reaction would have been even more brutal.

In Conclusion

The irony does not end there as to strange bedfellows and the war against Communism for the Nationalists, in waging their war against Communism the Nationalists found themselves in bed with Jonus Savimbi and his ‘anti-colonial’ movement UNITA fighting the proxy Cold War in Angola. By 1988, the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale found the National Party in a deep political hole and they had to use the South African Defence Force to very bravely (and successfully) fight their way out of it. To negotiate a peace, PW Botha and the National Party hung UNITA out to dry, agreed with Cuba and the MPLA’s Soviet alliance as to the withdrawal of their Communist forces from Angola so the Nationalists could go home and declare a ‘victory’ over Communism (the Cubans in turn could go home and declare they liberated Namibia see ‘The enemy of my enemy is my friend’).

Thereafter, just five very short years later, by 1994, the Nationalists of FW de Klerk had handed South Africa to the ANC/COSATU/Communist Party Tripartite Alliance with the Nationalists in coalition government again. The twists and turns of history now really show up the ‘full circle’ nature of history and why it repeats itself – because by April 2005 the ‘sunset clause’ was over and the National Party folded shop completely – and for political expediency again – their MP’s walked the floor to amalgamate with the ANC and their Communist labour alliance in a full merger. You could cut the irony with a knife at this stage.

How predictable is history in that it ‘repeats’ itself, and in light of all this ‘political expediency’, ‘irony’, ‘strange bedfellows’ and twisting by the party of Afrikaner nationalism, we have to genuinely ask ourselves how much of their constant criticism of Smuts over the 1922 Revolt was genuine and how much was just a case of political sandbagging?

Researched by Peter Dickens. Chief extract of the time-line of the Revolt taken from South African History Online (SAHO) 1922 Rand Rebellion. Other references include Wikipedia.

74 Squadron was formed during World War 1,Its first operational fighters were S.E. 5as in March 1918, and served in France until February 1919, during this time it gained a fearsome reputation and was credited with 140 enemy planes destroyed and 85 driven down out of control, for 225 victories. No fewer than Seventeen aces had served in the squadron, including one Victoria Cross Winner Major Edward Mannock. In this line up of aces was one notable South African, and this man came from Kimberley, Capt. Andrew Cameron Kiddie DFC, and he came from unassuming beginnings – he was one of Kimberley’s local bakers.

74 Squadron was formed during World War 1,Its first operational fighters were S.E. 5as in March 1918, and served in France until February 1919, during this time it gained a fearsome reputation and was credited with 140 enemy planes destroyed and 85 driven down out of control, for 225 victories. No fewer than Seventeen aces had served in the squadron, including one Victoria Cross Winner Major Edward Mannock. In this line up of aces was one notable South African, and this man came from Kimberley, Capt. Andrew Cameron Kiddie DFC, and he came from unassuming beginnings – he was one of Kimberley’s local bakers.

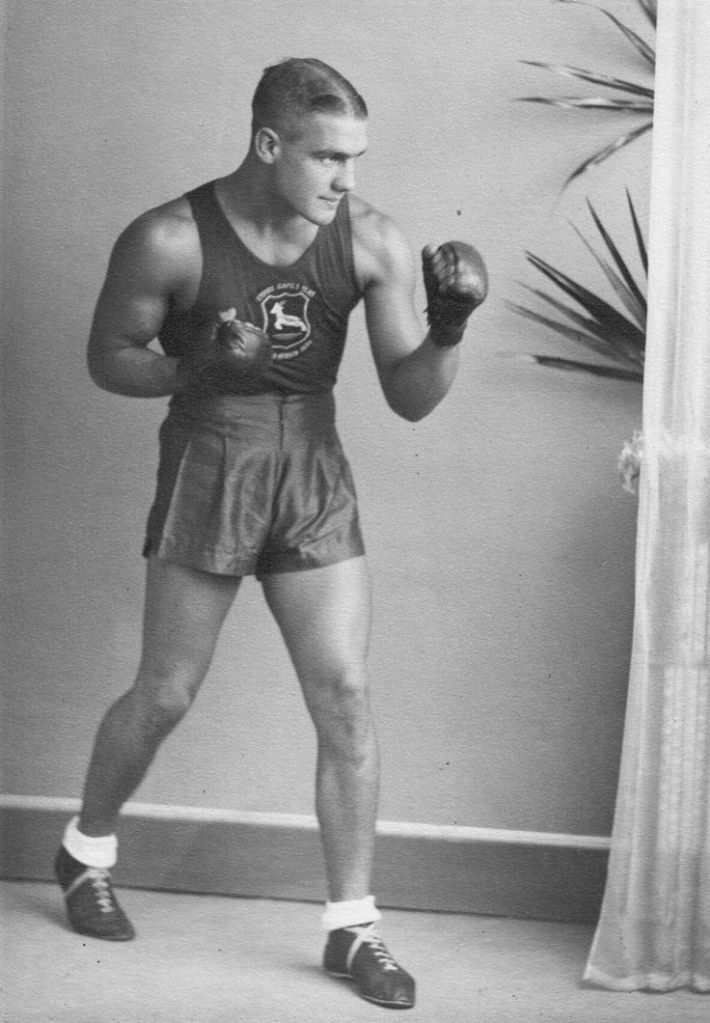

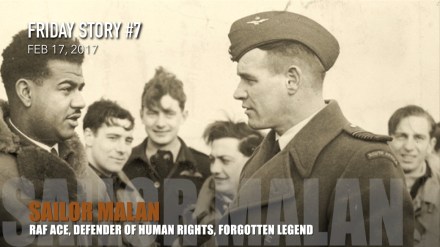

World War 2 would shape 74 Squadron as one of the best in The Royal Air Force. It became the front-line squadron which took the brunt of the attacks during The Battle of Britain, and this time the squadron was commanded by a formidable South African, Group Captain A G ‘Sailor’ Malan DSO & Bar DFC & Bar.

World War 2 would shape 74 Squadron as one of the best in The Royal Air Force. It became the front-line squadron which took the brunt of the attacks during The Battle of Britain, and this time the squadron was commanded by a formidable South African, Group Captain A G ‘Sailor’ Malan DSO & Bar DFC & Bar.

Air Vice-Marshal John Howe was one of the RAF’s most experienced and capable Cold War fighter pilots, whose flying career spanned Korean war piston-engined aircraft to the supersonic Lightning and Phantom.

Air Vice-Marshal John Howe was one of the RAF’s most experienced and capable Cold War fighter pilots, whose flying career spanned Korean war piston-engined aircraft to the supersonic Lightning and Phantom.

In retirement he was a sheep farmer in Norfolk, where he was known as the “supersonic shepherd”; he retired in 2004. He was a capable skier and a devoted chairman of the Combined Services Skiing Association. A biography of him, Upward and Onward, by Bob Cossey, was published in 2008. John Howe married Annabelle Gowing in March 1961; she and their three daughters survive him.

In retirement he was a sheep farmer in Norfolk, where he was known as the “supersonic shepherd”; he retired in 2004. He was a capable skier and a devoted chairman of the Combined Services Skiing Association. A biography of him, Upward and Onward, by Bob Cossey, was published in 2008. John Howe married Annabelle Gowing in March 1961; she and their three daughters survive him.

This time Sailor’s legacy has been carried forward by “Inherit South Africa” in this excellent short biography narrated and produced by Michael Charton as one of his Friday Stories – this one titled FRIDAY STORY #7: Sailor Malan: Fighter Pilot. Defender of human rights. Legend.

This time Sailor’s legacy has been carried forward by “Inherit South Africa” in this excellent short biography narrated and produced by Michael Charton as one of his Friday Stories – this one titled FRIDAY STORY #7: Sailor Malan: Fighter Pilot. Defender of human rights. Legend.

A tremendous reception awaited the orphans when they came ashore in Cape Town. So large was the group of children that the Cape Jewish Orphanage was unable to house them all, so 78 went on to Johannesburg.

A tremendous reception awaited the orphans when they came ashore in Cape Town. So large was the group of children that the Cape Jewish Orphanage was unable to house them all, so 78 went on to Johannesburg.

There are still a handful of conservative ‘Afrikaner nationalist’ white people in South Africa who would still toe the old Nationalist line on Smuts, that he was a ‘verraaier’ – a traitor to his people, his death welcomed. However, little do they know that many of the old Nationalist architects of Apartheid held Smuts in very high regard.

There are still a handful of conservative ‘Afrikaner nationalist’ white people in South Africa who would still toe the old Nationalist line on Smuts, that he was a ‘verraaier’ – a traitor to his people, his death welcomed. However, little do they know that many of the old Nationalist architects of Apartheid held Smuts in very high regard.

Smuts was honoured by many countries and on many occasions, as a standout Smuts was the first Prime Minister of a Commonwealth country (any country for that matter) to address both sitting Houses of the British Parliament – the Commons and the Lords during World War 2. To which he received a standing ovation from both houses.

Smuts was honoured by many countries and on many occasions, as a standout Smuts was the first Prime Minister of a Commonwealth country (any country for that matter) to address both sitting Houses of the British Parliament – the Commons and the Lords during World War 2. To which he received a standing ovation from both houses. Whilst studying law at Christ’s College at Cambridge University, he was rated as one of the top three students they have ever had (Christ’s College is nearly 600-year-old). The other two were John Milton and Charles Darwin.

Whilst studying law at Christ’s College at Cambridge University, he was rated as one of the top three students they have ever had (Christ’s College is nearly 600-year-old). The other two were John Milton and Charles Darwin.

The is a very big separation between race politics in the Smuts epoch and the Apartheid epoch. Race politics existed in South Africa during the Smuts era, of that there is no doubt. However Smuts was addressing it and political resistance on a really ‘mass’ basis from from these communities did not really exist at the time. Smuts and his politics are complex, he initiated violent counter action to any dissonance by striking miners or Afrikaner rebellions (whether Black or White, it mattered not a jot to him) but more often than not used dialogue, and a lot can be said to the fact that the ANC in fact supported Smuts’ decision to take the country to war in 1939/40.

The is a very big separation between race politics in the Smuts epoch and the Apartheid epoch. Race politics existed in South Africa during the Smuts era, of that there is no doubt. However Smuts was addressing it and political resistance on a really ‘mass’ basis from from these communities did not really exist at the time. Smuts and his politics are complex, he initiated violent counter action to any dissonance by striking miners or Afrikaner rebellions (whether Black or White, it mattered not a jot to him) but more often than not used dialogue, and a lot can be said to the fact that the ANC in fact supported Smuts’ decision to take the country to war in 1939/40.