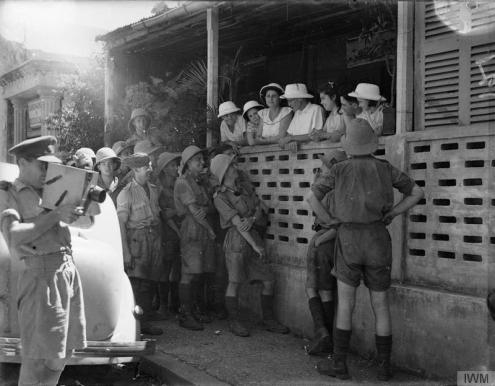

This is an extraordinary featured photograph for a variety of reasons. This is Hauptmann (Captain) Hans-Joachim Marseille, the German WW2 Fighter Ace known to the Axis Forces as “The Star of Africa” on the extreme left and Corporal Mathew ‘Mathias’ Letulu, a South African Prisoner of War who was pressed into becoming his ‘batman’ (personal assistant to an officer) in 1942 but eventually became his close and personal friend, is seen on the extreme right of the photograph.

It’s quite intriguing that Hans-Joachim Marseille had a South African assistant on the one hand when on the other hand he was the most feared of the German Pilots in the North African campaign, arguably one of the best combat pilots the world has ever seen, he clocked up quite a number of South African Air Force “kills” in his enormous tally of destroying well over 100 Allied aircraft – consisting mainly of aircraft from the Royal Air Force (RAF), the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and the South African Air Force (SAAF).

It’s equally a measure of Hans-Joachim Marseille as a man in that he directly baulked against the Nazi policies of racial segregation and openly befriended a Black man, especially amazing considering his role as a senior commissioned officer in the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) and hero of the Reich.

Over time, Marseille and “Mathias” Letulu became inseparable. Marseille was concerned how Letulu would be treated by other units of the Wehrmacht and once remarked

“Where I go, Mathias goes.”

Marseille secured promises from his senior commander, Neumann, that if anything should happen to him (Marseille) Cpl “Mathias” Letulu was to be kept with the unit. Unusual behaviour for a German officer in the Third Reich, but Marsaille was no card carrying member of the Nazi party, in fact he despised them.

No ardent Nazi

In terms of personality Hans-Joachim Marseille was the opposite of highly disciplined German officer, he was “the funny guy” and almost kicked out of Luftwaffe several times for his antics. The only reason he wasn’t was because his father was a high ranking WW I veteran and an army officer and Hans-Joachim Marseille tested how far this protection would go.

If you look “misbehaving scoundrel” in dictionary there should be an image of Hans’ smirking face next to it. On one occasion he actually strafed the ground in front of his superior officer’s tent. He could have been court marshalled for that alone, but by then he was starting to demonstrate his superior pilot skills as an upcoming Fighter Ace.

He hated Nazis and he despised authority in general and always had strained relations with his authoritarian father who was the model of a strict Prussian officer. Hans was truly the opposite of his father.

His American biographers Colin Heaton and Anne-Marie Lewis recall in ‘The Star of Africa’ that he once landed on the autobahn simply to relieve himself. Tired of his undisciplined behaviour, a superior officer had him transferred to North Africa in 1941. Here he thrived, his dazzling record earned him the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords, and Diamonds, and acclaim at home. But the record suggests he was no ardent Nazi.

He listened to banned Jazz music openly, drank a lot and sometimes showed up to service smelling of booze and in hangover, he was a known womanizer, going against Nazi ideology in every possible manner – and getting away with it.

An incident happened which really shows the metal and attitude of the man. It occurred when Hans-Joachim Marseille was summoned to Berlin as Hitler wanted to present him with decorations. As a gifted pianist Marseille was invited to play a piece at the home of Willy Messerschmitt, an industrialist and the designer of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter Marseille had achieved so much success in.

Guests at the party included Adolf Hitler, party chairman Martin Borman, Hitler’s deputy and Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring, head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler and Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. After impressing them with a display of piano play for over an hour, including Ludwig van Beethoven’s Für Elise, Marseille proceeded to play American Jazz, which was considered degenerate in Nazi ideology. Hitler stood, raised his hand, and said “I think we’ve heard enough” and left the room.

Magda Goebbels found the prank amusing and Artur Axmann recalled how his “blood froze” when he heard this “Ragtime” music being played in front of the Führer.

But a more telling incident of his attitude to Nazism was to come. On one occasion when he was summoned to Germany, he noted that Jewish people had been removed from his neighbourhood (including his Jewish family Doctor who delivered him) and grilled his fellow officers as to what happened to them – what he then heard were the plans for the Final Solution – the extermination of the Jews of Europe. This shocked him to the core and he actually went AWOL (Absent without Leave), he became a de facto deserter and went to Italy were he went into hiding ‘underground’.

The Nazi German Gestapo (Secret Police) however managed to track him down and forced him to return to his unit where other pilots noticed that he appeared severely depressed, concerned and wasn’t anything like his normal happy self that they were used to.

Friendship with Corporal Mathew Letulu

Marseille’s friendship with his ‘batman’ (personal helper) is also used to show his anti-Nazi character. In 1942 Marseille befriended a South African Army prisoner of war, Corporal Mathew Letulu. Marseille took him as a personal helper rather than allow him to be sent to a prisoner of war camp in Europe.

“Mathias” was the nickname given Corporal Mathew Letulu by his captors. Cpl Letulu was part of the South African Native Military Corps and was taken as a Prisoner of War (POW) by the Germans on the morning of 21 June 1942 when Tobruk and the defending South Africans under General Klopper were overrun by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

‘Black’ POW where treated differently to White ‘POW’ by Nazi Germany, instead of mere confinement under the conventions, Black POW were but to unpaid ‘labour’ assisting the Nazi cause, resistance to which was a grim outcome. Letulu was put to work by the Germans – initially as a driver. The vehicle belonged to 3 Squadron of Jagdgeschwader – or Fighter Wing – 27 (JG 27) based at Gazala, 80km west of Tobruk. Here, Letulu came to the attention of the reckless and romantic Hans-Joachim Marseille.

By this time Letulu had advanced a little in his lot to a helper in 3 Squadrons club casino, where he took a particular liking to Marseille. In need of personal assistants for officers (known in the military as a “batman”) some POW’s where snapped up by German Officers, Hans-Joachim Marseille was no different and Cpl Letulu was taken on initially as his batman, but very quickly became a close friend.

Marseille knew that as his kill score grew, the chance of him being pulled from the front lines increased every day, and if he was to be taken away, Cpl “Mathias” Letulu, who because he was a black man, might be in danger given the Nazi racial philosophy. With utmost seriousness, he had his fellow pilot Ludwig Franzisket promise to become Mathias’ protector should Marseille lose the capability to be in that role.

Corporal Letulu also knew that by sticking with Marseille he stood a better chance of surviving the war and eventually escaping, and because they viewed each other in an extremely positive light, Letulu made Marseille’s life in the combat zone as comfortable as possible.

The following on their unique bond comes from “German Fighter Ace – Hans-Joachim Marseille, The life story of the Star of Africa” by Franz Kurowksi.

“Through few odd twists of fate Hans had Mathew assigned to his personal assistant but he treated him in every way like a friend, having long talks with him and possibly even sharing alcohol and listening to music together, just hanging out like a couple of friends who happened to be in a war and on different sides.

Besides Mathew, Hans would often see other captured Allied pilots and talk to them in English and socialise. Hans would also violate a direct order not to notify the enemy of the fate of their pilots – he would take off solo with a parachute note explaining the names of the captured pilots and that they were alive and well. As he flew over enemy airfields to drop these notes he would be attacked by AA fire, so he was risking his life to let the families of his enemy pilots know that the pilots were alive and well – or dead, removing their MIA (Missing in Action) status. According to various sources he was like that. Person who believed in chivalry who’s country was taken over by Nazis.

Eventually Hans would become even protective of Mathew especially against the Nazis”

The “Star of Africa”

Hans-Joachim Marseille’s record of 151 kills in North Africa where nothing short of staggering – he destroyed Allied (RAF, SAAF and RAAF) squadrons shooting down One Hundred and One (101) Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk/Kittyhawk fighters, 30 Hawker Hurricane fighters, 16 Supermarine Spitfire fighters, Two Martin A-30 Baltimore bombers, One Bristol Blenheim bomber; and One Martin Maryland bomber.

Hans-Joachim Marseille with Hawker Hurricane MkIIB of 274. Squadron RAF, North Afrika – 30 March 1942 (coloured)

As a fighter pilot Marseille always strove to improve his abilities. He worked to strengthen his legs and abdominal muscles, to help him tolerate the extreme ‘G forces’ of air combat. Marseille also drank an abnormal amount of milk and shunned sunglasses, to improve his eyesight.

To counter German fighter attacks, the Allied pilots flew “Lufbery circles” (in which each aircraft’s tail was covered by the friendly aircraft behind). The tactic was effective and dangerous as a pilot attacking this formation could find himself constantly in the sights of the opposing pilots. Marseille often dived at high-speed into the middle of these defensive formations from either above or below, executing a tight turn and firing a two-second deflection shot to destroy an enemy aircraft.

Marseille attacked under conditions many considered unfavourable, but his marksmanship allowed him to make an approach fast enough to escape the return fire of the two aircraft flying on either flank of the target. Marseille’s excellent eyesight made it possible for him to spot the opponent before he was spotted, allowing him to take the appropriate action and manoeuvre into position for an attack.

In combat, Marseille’s unorthodox methods led him to operate in a small leader/wingman unit, which he believed to be the safest and most effective way of fighting in the high-visibility conditions of the North African skies. Marseille “worked” alone in combat keeping his wingman at a safe distance so he would not collide or fire on him in error.

In a dogfight, particularly when attacking Allied aircraft in a Lufbery circle, Marseille would often favour dramatically reducing the throttle and even lowering the flaps to reduce speed and shorten his turn radius, rather than the standard procedure of using full throttle throughout. Emil Clade said that none of the other pilots could do this effectively, preferring instead to dive on single opponents at speed so as to escape if anything went wrong.

Marseille’s South African associations went beyond his bond with Cpl “Mathias” Letulu and was far more lethal in respect to South African pilots. In the weeks before the two met, Marseille is credited with shooting down three SA Air Force pilots west of Bir-el Harmat on May 31, including Bishops’ old boy Major Andrew Duncan (who was killed), and three days later, another six South African Air Force “kills” in just 11 minutes, three of whom were high-scoring aces. One of them, Robin Pare, was killed in the combat.

Death of Hauptmann Hans-Joachim Marseille

On 30 Sep 1942, Marseille’s brilliant total record of 158 career-kills came to an end (151 of them with JG 27 in North Africa).

After the engine of his Bf 109G fighter developed serious trouble, he bailed out of the aircraft close to friendly territory under the watchful eyes of his squadron mates. To their horror, Marseille’s fighter unexpectedly fell at a steep angle as he bailed out, the vertical stabilizer striking him across the chest and hip. He was either killed instantly or was knocked unconscious; in either case, his parachute did not deploy, and he struck the ground about 7 kilometers south of Sidi Abdel Rahman, Egypt.

Messerschmitt Bf 109F-4 , Hans Joachim Marseille, colorised picture.

His friend and fellow JG 27 pilot and Knights Cross recipient Hauptmann Ludwig Franzisket along with the squadron surgeon Dr. Winkelmann, were the first two to arrive on the scene, bringing Marseille’s remains back to the base.

Mathias was the first to greet them, and the following is accounted from a memoir by Wilhelm Ratuszynski.

Although the heat didn’t encourage any activity, something told Mathias to wash Hans’ clothes. Hans liked to change into a fresh uniform after the flight. He always liked to look presentable. Mathias opted to use gasoline this time. They wash would dry in just few minutes.

Usually, this was done by scrubbing uniforms with sand to rid it of salt, oil and grime. Everything was in short supply. Being a personal batman for Hans-Joachim Marseille, the most famous Luftwaffe pilot, had its advantages. For instance he was given a little of aircraft fuel for washing. Mathias liked being Jochens servant and he liked Jochen himself.

They were friends. Mathias had barely started his chore, when the sound of approaching aircraft signaled to ground personnel to change torpidness for activness. Mathias put the lid on the soaking uniforms and started to walk towards the landing aircraft. He was looking for familiar plane which supposed to have number 14 painted in visible yellow on fuselage. It was supposed to land last. He noticed that three planes were missing, and last one to touch down had different number on it.

Unalarmed, he turned toward Rudi who had already jumped on the ground from wing of his 109. He saw Mathias coming and cut short his conversation with his mechanic. His face was somber when he looked at Mathias and slowly shook his head. And Mathias understood immediately. He kept looking straight into Rudi’s face for few more seconds, slowly turned and walked away. He noticed a strange sensation. No anger, sorrow, grief, nor resignation. He was calm yet something gripped his throat. Muscles on his neck tightened and he found it hard to swallow. He walked for few minutes without noticing others who were staring at him. He came to Jochen’s colorful Volks (volkswagen car) called “Otto” and sat behind steering wheel. For a moment he looked like he wanted to go somewhere, but climbed out and approached the soaking uniforms.

He looked at the canvas bag with initial H-J.M laying right beside it. He reached into his breast pocket for matches. Slowly but without any hesitation he struck a match and threw it on the laundry. Flames that burst out added to the already scourging heat. At that moment last rotte was flying in. Mathias intuitively lifted his head, following them. The lump in his throat got bigger.

While the entire squadron was devastated at the loss of such a great fighter ace, Mathias, despite having known Marseille only for a short time, was deeply depressed at the loss of a dear friend.

Marseille was initially buried in a German military cemetery in Derna, Libya during a ceremony which was attended by leaders such as Albert Kesselring and Eduard Neumann. He was later re-interned at Tobruk, Libya.

Ludwig Franzisket

After Marseille’s death, as promised to his friend, Hauptmann Ludwig Franzisket took Cpl Letulu in, and in turn he became his personal servant. Cpl Letulu remained with the Squadron even after Franzisket was forced to bail out whereby he too struck the vertical stabilizer, shattering a leg in the process. After been nursed to health, Franzisket returned to his Squadron and Cpl Letulu continued serving him in Tunisia, Sicily, and finally Greece.

By the summer of 1944 the situation there had grown critical with a British invasion of the Greek continent imminent. The chance had come to “smuggle” Cpl. “Mathias” Letulu into one of the hastily established POW camps, where he could then be “liberated” by the British. Franzisket planned this coup together with Hauptmann Buchholz. “Mathias “became “Mathew” again and was a corporal in the South African Division. Everything went off without a hitch. He was set free by British troops in September of 1944 and allowed to return home at the end of hostilities.

Reunion

By coincidence, after the war, former members of JG 27 learned that Cpl “Mathias” Letulu was still alive. They immediately sent him an invitation, paid for the journey and other expenses, and finally, at the tenth reunion of the Deutsches Afrikakorps in the fall of 1984, they were once again reunited with their old South African friend.

The former pilots were elated to see him and invitations rained from all around. The following words, spoken in German as a tribute to Hans-Joachim Marseille by “Mathias” Letulu at the happy conclusion of his odyssey, and it gives some insight into the bond which had united Letulu with his German friend:

“Hauptmann Marseille was a great man and a person always willing to lend a helping hand. He was always full of humor and friendly. And he was very good to me.”

In 1989, a new grave marker and a new plaque was placed at his grave site; Marseille’s surviving Luftwaffe comrades attended the event, including his Allied friend – Mathew “Mathias” Letulu who flew out specifically from South Africa to attend the ceremony.

Related work and links:

Rommel’s aide-de-camp; Rommel’s aide-de-camp was a South African

Jack Frost, The South African Air Force’s highest scoring Ace – Jack Frost

Researched by Peter Dickens

Although The Comrades Marathon is an independent commercial concern now, The South African Legion has continued its association to the Comrades Marathon over the years and encourages all participants to wear a Remembrance Poppy in recognition of this history and the sacrifice of the fallen. In this respect the Comrades Marathon is still in fact a “living memorial” to the Great War (World War 1).

Although The Comrades Marathon is an independent commercial concern now, The South African Legion has continued its association to the Comrades Marathon over the years and encourages all participants to wear a Remembrance Poppy in recognition of this history and the sacrifice of the fallen. In this respect the Comrades Marathon is still in fact a “living memorial” to the Great War (World War 1).