August 2017 marks the centenary of the report to form the Royal Air Force (RAF), the idea of an independent Air Force from Navy or Army control is now officially 100 years old, and one key South African statesman, General Jan Smuts, gave birth to it.

Smuts in WW1

Today, if you walk into the Royal Air Force Private Club in Mayfair, London you are greeted by a bust of Jan Smuts in the foyer, it stands there as an acknowledgement to the man who founded what is now one of the most prestigious and powerful air forces in the world – The RAF.

So how did it come to be that a South African started The Royal Air Force and why the need to have a separate and independent arm of service?

Simply put, during World War 1, the British Army and the Navy developed their own air-forces in support of their own respective ground and naval operations. The Royal Flying Corps had been born out of the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers and was under the control of the British Army. The Royal Naval Air Service was its naval equivalent and was controlled by the Admiralty.

However, the use of air power in World War 1 was developing beyond the immediate tactical use of aircraft by the Navy and the Army. In Great Britain the civilian population had been on the receiving end of extensive German bombing raids dropped from flying Zeppelin airships, the public outrage and the psychological effects of this bombing was having a significant impact on British politicians.

In reaction to this, the politicians proposed the creation of a long-range bombing force both as a retaliation and also as a means of disrupting enemy war production. There were also continuing concerns about aircraft supply and priorities between the services.

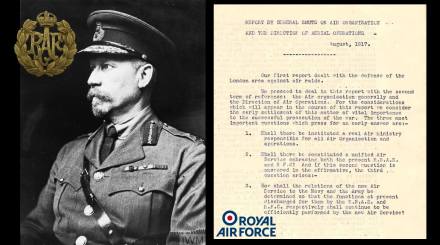

The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George asked General Jan Smuts to join his War Cabinet (the supreme authority governing Great Britain and her Empire’s forces in World War 1). Lloyd George then commissioned General Jan Smuts to report on two issues:

Firstly to look into arrangements for Home Defence against bombing and secondly, air organisation generally and the direction of aerial operations. Smuts is generally accredited with improving British air defence and answering the first priority.

However it was ‘Smuts report’ of August 1917 in response to the second of these questions that led to the recommendation to establish a separate Air Service. In making his recommendations Smuts commented that

However it was ‘Smuts report’ of August 1917 in response to the second of these questions that led to the recommendation to establish a separate Air Service. In making his recommendations Smuts commented that

“the day may not be far off when aerial operations with their devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war, to which the older forms of military and naval operations may become secondary and subordinate”.

Given this new dimension he commented that it was important that the design of aircraft and engines for such operations should be settled in accordance with the policy which would direct their future strategic employment. On these grounds he argued there was an urgent need to create an Air Ministry and that this Ministry should sort out the amalgamation of the two air services.

The War Cabinet accepted this recommendation to amalgamate the two separate air forces under one single and independent Air Force. Smuts was then asked to lead an Air Organisation Committee to put it into effect. The Air Force Bill received Royal assent from the King on the 29 November 1917, which gave the newly formatted Air Force the prefix of ‘Royal’ (up to that point the idea was to call it the ‘Imperial Air Force’).

The War Cabinet during WW1, Smuts seated bottom, far right

The RAF was officially formed on the 1 April 1918 with the amalgamation of the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps. Following which Lord Rothermere was appointed on 3 January 1918 as the first Secretary of State for Air and an Air Council established.

To emphasise the merger of both army and naval aviation in the new service, to appease the ‘senior service’ i.e. the Navy, many of the titles of officers were deliberately chosen to be of a naval character, such as Flight Lieutenant, Wing Commodore, Group Captain and Air Commodore.

Royal Air Force

The newly created Royal Air Force was the most powerful air force in the world on its creation, with over 20,000 aircraft and over 300,000 personnel (including the Women’s Royal Air Force). It now qualifies as the oldest independent Air Force in the World.

General Smuts was to take his recommendations and findings across to form an independent South African Air Force (SAAF). Smuts appointed Colonel Pierre van Ryneveld as the Director Air Services (DAS) with effect from 1 February 1920 with instructions to establish an air force for the South African Union. This date is acknowledged as marking the official birth of the SAAF. The SAAF now qualifies as the second oldest independent Air Force in the world.

South African Air Force

In a nutshell, both the RAF and SAAF as we know them today, were given to us by Jan Smuts as a founding father. Funnily, Smuts was often criticised domestically as ‘Slim’ Jannie (clever little Jan), a term Smuts hated as it was coined by the Hertzog Nationalists to mean that Jan Smuts was too clever for his ‘volk’ (peoples) and therefore out of touch, it was done for political expediency at Smuts’ personal expense. Smuts disliked the term as it as it ironically belittled the Afrikaner and positioned his people as ‘simpletons’, something Smuts fundamentally disagreed with, and something they most certainly are not.

That said, domestically Smuts’ political adversaries in the opposition National Party carried on with this belittling ‘Slim Jannie’ nickname to further criticise his ability to command at a strategic level, stating that his approach was too ‘intellectual’ for effective command.

All modern military strategy is formulated on joint arms of service with an independent air arm. You only have to look to any modern military construct of any military superpower today to see just what a visionary and strategist Jan Smuts was. The proof of his ability to command strategically is in the pudding. Smuts’ ground-breaking report in August 1917 now guides all modern strategic military planning by simple way of how the arms of service are now constructed (Army, Navy, Air Force i.e. ground, sea, air), how they co-ordinate with one another and how they are commanded.

Written and researched by Peter Dickens. References – Birth of the Royal Air Force (Royal Air Force Museum), Imperial War Museum and Wikipedia. Images copyright, Imperial War Museum.

Jackie also encountered a V-1 flying bomb in the air over Surrey while flying a Tempest. She altered course, fully intending to attempt to topple it with her wing tip but failed to catch up to it. The standard practice in dealing with a ‘doodlebug’ (as the V1 was nicknamed) was a wingtip topple, it threw the flying bomb’s gyro off its intended target and sent it into open countryside instead of a city. However the trick was to fly faster than the rocket to do it. The picture featured shows this remarkable manoeuvre between a Spitfire and an unmanned V1 flying bomb.

Jackie also encountered a V-1 flying bomb in the air over Surrey while flying a Tempest. She altered course, fully intending to attempt to topple it with her wing tip but failed to catch up to it. The standard practice in dealing with a ‘doodlebug’ (as the V1 was nicknamed) was a wingtip topple, it threw the flying bomb’s gyro off its intended target and sent it into open countryside instead of a city. However the trick was to fly faster than the rocket to do it. The picture featured shows this remarkable manoeuvre between a Spitfire and an unmanned V1 flying bomb. She was a member of one very elite group and one of only five women to be awarded full RAF wings during the war, Jackie even campaigned to become the first woman to break the sound barrier but was prevented from doing so by the powers that be.

She was a member of one very elite group and one of only five women to be awarded full RAF wings during the war, Jackie even campaigned to become the first woman to break the sound barrier but was prevented from doing so by the powers that be.

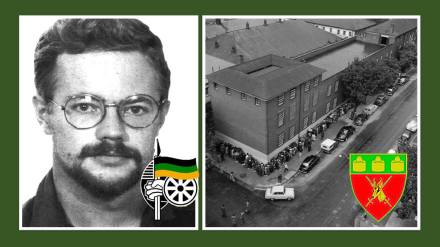

On 30 July 1987, a bomb exploded at the Witwatersrand Command’s Drill Hall injuring 26 people (no deaths), the injured were made up of a mix of both military personnel and by-standing civilians. The Drill Hall was targeted because not only was it a military installation, it was also the same historic Hall in which the 1956 Treason Trial took place and significant to ‘struggle’ politics.

On 30 July 1987, a bomb exploded at the Witwatersrand Command’s Drill Hall injuring 26 people (no deaths), the injured were made up of a mix of both military personnel and by-standing civilians. The Drill Hall was targeted because not only was it a military installation, it was also the same historic Hall in which the 1956 Treason Trial took place and significant to ‘struggle’ politics.

At her request Klaasen and Grosskopf met for a few minutes in private after the hearing and then they both posed briefly and rather awkwardly for this photograph (note the body language). Neither of them elaborated on their meeting, Klaasen was only prepared to say that it had been good.

At her request Klaasen and Grosskopf met for a few minutes in private after the hearing and then they both posed briefly and rather awkwardly for this photograph (note the body language). Neither of them elaborated on their meeting, Klaasen was only prepared to say that it had been good.

On the eve of World War II the Union of South Africa found itself in a unique political and military quandary. Though closely allied with Great Britain as a co-equal Dominion under the 1931 Statute of Westminster with the British king as its head of state, South Africa had as its Prime Minister on 1 September 1939 Barry Hertzog, the leader of the pro-Afrikaner anti-British National party that had joined in a unity government as the United Party.

On the eve of World War II the Union of South Africa found itself in a unique political and military quandary. Though closely allied with Great Britain as a co-equal Dominion under the 1931 Statute of Westminster with the British king as its head of state, South Africa had as its Prime Minister on 1 September 1939 Barry Hertzog, the leader of the pro-Afrikaner anti-British National party that had joined in a unity government as the United Party. To celebrate Smut’s victory in Parliament that day a special button/lapel badge was made inscribed with 4-9-1939 for the party faithful.

To celebrate Smut’s victory in Parliament that day a special button/lapel badge was made inscribed with 4-9-1939 for the party faithful. A very interesting part of the sequences of declarations of war against Germany, was that of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and it stands out as a unique one. The Southern Rhodesian government almost immediately followed the British declaration of war with their own. They can even be said to hold the mantle as the very first of the British Dominions and Colonies to stand by Britain in their hour of need. Steadfast and swift in support of their ‘motherland’ – The United Kingdom, no quibble about it either, as there was no long parliamentary debate over the issue – it came without even a second thought on the matter. In all 26 000 Rhodesians volunteered to fight during World War 2.

A very interesting part of the sequences of declarations of war against Germany, was that of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and it stands out as a unique one. The Southern Rhodesian government almost immediately followed the British declaration of war with their own. They can even be said to hold the mantle as the very first of the British Dominions and Colonies to stand by Britain in their hour of need. Steadfast and swift in support of their ‘motherland’ – The United Kingdom, no quibble about it either, as there was no long parliamentary debate over the issue – it came without even a second thought on the matter. In all 26 000 Rhodesians volunteered to fight during World War 2. In terms of the semantics of the ‘term ‘standing alone’ after Dunkirk, in many cases the Commonwealth countries did not have immediate operational readiness to come alongside the UK in the summer of 1940. However we must remember that the Battle of Britain (when Britain really ‘stood alone’) was an air battle, where a ‘few’ pilots held off the German assault – and alongside the 2353 British pilots stood 574 pilots from other countries – 24%, – a quarter of the combat force. Most of them came from the Commonwealth countries (342 pilots in total including Rhodesians and South Africans). So Britain never really ‘stood alone’ in that context either.

In terms of the semantics of the ‘term ‘standing alone’ after Dunkirk, in many cases the Commonwealth countries did not have immediate operational readiness to come alongside the UK in the summer of 1940. However we must remember that the Battle of Britain (when Britain really ‘stood alone’) was an air battle, where a ‘few’ pilots held off the German assault – and alongside the 2353 British pilots stood 574 pilots from other countries – 24%, – a quarter of the combat force. Most of them came from the Commonwealth countries (342 pilots in total including Rhodesians and South Africans). So Britain never really ‘stood alone’ in that context either.

Such a big deal was made of this victory, that a special commemorative coin was even stamped to celebrate Capt. Pyott’s actions and resultant DSO. Zeppelins were so feared by the British public they were branded ‘Baby Killers’ as the bombing of civilians carried with it such a public outrage. The commemorative medal carried Capt Ian Pyott’s profile, the year and the letters DSO, it was presented to him at Hendon Aerodrome in England by none other than General Jan Smuts.

Such a big deal was made of this victory, that a special commemorative coin was even stamped to celebrate Capt. Pyott’s actions and resultant DSO. Zeppelins were so feared by the British public they were branded ‘Baby Killers’ as the bombing of civilians carried with it such a public outrage. The commemorative medal carried Capt Ian Pyott’s profile, the year and the letters DSO, it was presented to him at Hendon Aerodrome in England by none other than General Jan Smuts.

Especially for the South Africans, The song was published in South Africa in a wartime leaflet, with an anonymous English translation, as ‘Lili Marleen: The Theme Song of the Eighth Army and the South African 6th Armoured Division’ (quite ironically).

Especially for the South Africans, The song was published in South Africa in a wartime leaflet, with an anonymous English translation, as ‘Lili Marleen: The Theme Song of the Eighth Army and the South African 6th Armoured Division’ (quite ironically). Innovative as ever, the biscuit part was shaped the same as for “Gypsy Creams”, but the biscuit part (referred to as the shell) was improved and it was sandwiched with a chocolate filling instead, no doubt provided by Cadbury’s Chocolates.

Innovative as ever, the biscuit part was shaped the same as for “Gypsy Creams”, but the biscuit part (referred to as the shell) was improved and it was sandwiched with a chocolate filling instead, no doubt provided by Cadbury’s Chocolates.