Not unusually, whenever there is a post of a Boer farm burning on a Boer War social media site there is an inevitable indignation and disgust targeted at the British and usually accompanied by a torrent of abuse from a community still fractured by this conflict.

On my blog, The Observation Post, I even had a person write to me personally and state how dare I allude to Boer aggression as a Casus Belli of the war when “the British brought innocent Boer women and children into the war in the first place” – the indignation at the ‘destruction of innocents’ and rather misdirected raw hate at me highly apparent, a quoted figure of Boer women and children sacrificed almost immediately referenced (usually inflated) – and it’s a common theme and a common retort – I see it all the time on all sorts of forums. It’s the kind of retort that is the result of decades of indoctrination and propaganda – and it’s simply completely disconnected with any semblance of full truths or balance.

So, here’s a little balance and understanding of a ‘full-truth’. At the beginning of the South African War (1899-1902), it was the Boers who commenced with creating a civilian refugee crisis, not the British, and the Boers subsequently invaded, besieged and ransacked entire British towns and territories – not only Johannesburg, but on sovereign British territory in addition, the ransacking of Dundee a case in point – burning farms and looting – leaving civilians with no shelter or refugee camps and simply chasing them into the hinterland without food or assistance.

So, let’s account who started what, and let’s account the carnage and scale of civilian casualties and who the really affected parties are – and I think you’ll be a little surprised to learn something that is not part of the old nationalist narrative of this war. Let’s begin at the beginning.

The Johannesburg Exodus

Starting in September 1899 and into October 1899 is a civilian refugee crisis on a significant scale, the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) issue a directive which sees the largest city in the republic empty out of nearly all its inhabitants.

What follows are first hand account of the initial “stampede” of ‘foreign’ (Uitlander) residents fleeing Johannesburg – many to be disposed of their property at the beginning of the war. In the end some 50,000 ‘foreign’ residents of the Transvaal were shipped out in cattle trucks and coal carts creating a refugee crisis of note (6,000 left in cattle trucks over just two days alone). Many were afforded no food or water and there are documented cases of deaths and even births in these cattle trucks and open top coal carts – the dead were buried next to the railway lines. Many of these refugees arrived in places like Durban, Cape Town, East London or Port Elizabeth and those who could not find rented, friendly or temporary accommodation were found to be loitering in parks and on the streets with no place to go, sleeping in the open and subject to the elements. The Boers idea being to chase them out of their homes in the ZAR and empty Johannesburg of its “uitlander” problem … and the British should somehow deal with the crisis.

In addition to the 50,000 odd whites departing Johannesburg – it is estimated that some 78,000 Black mine labour and workers fled Johannesburg between September and October 1899, many on foot arriving home in their villages penniless (their money, the last month of their wages, was confiscated by the ZAR government), and they are destitute, malnourished and exhausted (see Black People and the South African War 1899-1902. By Peter Warwick).

Notwithstanding the scale of this forced displacement of civilians – these unarmed ‘foreigners’ and their labour made up the majority of residents in the republican state – the “minority” chasing them out at gun-point.

Here’s the account by a white “British” Bradford man, writing to his parents, from Port Elizabeth, and he gave a vivid picture of the flight (bear in mind this is just the opening of what became a mass exodus).

“When I wrote you a short note on September 29th, 1899, from Johannesburg, I did not expect to have to clear out so soon afterwards, but there was very little time given us to consider. The Boers were commandeering all the Outlanders’ property as a war tax; they claimed all the horses on the mines, and behaved most insultingly to any Englishman they could come across. The way the Boers were treating us was simply outrageous. They are worse than Kaffirs, so I cleared out as quickly as I could.

There were 1500 people left Johannesburg by the same train, and nearly as many left on the platform. I had an awful journey down. We saw all the women and children in the closed carriages, whilst we men had to go in open coal trucks. About two hours after we started there was thunder, lightning, and heavy rain, which continued until we reached Kronstadt next day. Of course, we were all drenched to the skin. There we had some “scoff,” for which we had to pay 3s. 6d. each. At ordinary times the charge is not more than 2s. per meal.

The Orange Free State officials provided us with cattle trucks, which, being covered, were a little better than open coal trucks, and shielded us from the rain. We travelled right through the Free State in this kind of conveyance, and after crossing the border into the colony at Newport we were put into civilised carriages for the rest of our journey. Altogether the journey took us three days and three nights. It was difficult to get quarters, for the place is crowded. Anyhow, we managed to get a room —I and another fellow—for which we had to pay a pound for one week.

There are about 5000 refugees from the Transvaal down here, and I hear that at Cape Town and Durban people are sleeping in churches, warehouses, and, in fact, anywhere they can get a covering for their heads. People who came down here two or three months ago are at their wits’ end, their money being finished, and they having to rely on charity for a bite to eat. Whole families are starving.

The British Government ought to help these subjects, as they are forced to leave their livelihood, and all because the English Government will not hurry up and settle things one way or the other. Johannesburg is very nearly empty. Nearly all the mines have been closed down. All the storekeepers have barricaded their places up and discharged their workpeople, and the principals have cleared out, leaving their goods and property to look after themselves. Thousands of people who a few months ago were doing a nice business are now ruined, and their labours for years past are all wasted. The Boers will not allow them to remove their stock, produce, or anything else.”

Of the exodus from Johannesburg a nurse named Miss Colina Macleay records the ordeal:

“I caught the first train, crowded beyond anything you can imagine, and had to go into a coal truck with fifty white and black people, all mixed, including coolies, samies, Kaffirs, Cornish miners, and other whites. On our way out of the Transvaal we were detained at lots of stations, and insulted everywhere. The heat was intense, with a broiling sun and nothing to protect us from it. And we also suffered from thirst. When we saw a water pump we would try to get out, but guns were pointed at us and we were threatened if we dared to move. All the time the fellows at the stations were drinking and laughing and wasting the water to tempt us all the more … one poor child died in our truck, and our train stopped for a few minutes to bury the body at the railway side on the veldt. I think I shall never forget the cries of the poor children for meat and drink … At length we arrived at Delagoa Bay at one o’clock in the morning, only to find the place crowded, with people lying in the station, parks, and other available corners. A Committee of kind ladies and gentlemen and the Governor met all the refugee trains, and did the best they could for the poorer ones. As I was a nurse and in uniform I was taken to the Salvation Army Hall, and I had there to lie on the floor with hundreds of others (women and children) …”

To quote Steven’s ‘Complete History of the War’:

“The expulsion of aliens was the order of the (Republican) States, and protection was withdrawn from the mines, which of course came to a stand still. With the opening of October (1899) South Africa became astir with warlike preparations, Burghers and British troops hurrying to the- front, and with martial law (in the Boer Republics) came plunder. Bullion worth a million being conveyed from the Rand to Cape town was seized (by the Boers) and sent to Pretoria —with a ‘receipt’ for the same. It was minted into coin”.

The ransacking of Natal

The Boer Republics declared war on Great Britain on the 11th October 1899. This was achieved by two actions, both of which involved invading two sovereign British territories by way of declaration of hostilities. The first was the cutting of the railway line near Kimberley in the Cape Colony and the second was the invasion of the Natal Colony.

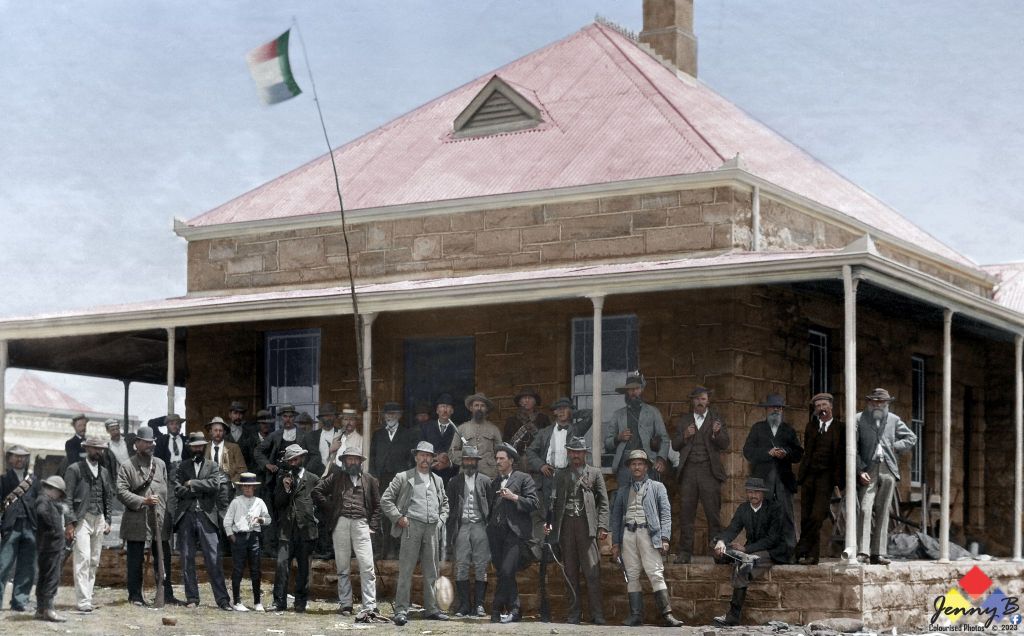

The invasion of Natal is marred by wholesale looting and the ransacking of British towns and farms in northern Natal. Despite Boer proclamations from their war council prohibiting both looting and even annexations. The Republican forces on the ground behave with impunity and ignore their directives, they re-name towns, declare sections of Natal as annexed to the ZAR, appoint Landrosts, hoist the Vierkleur over public buildings and embark on a looting and destructive spree of note (Newcastle is re-named Viljoensdorp and Dundee is re-named Meyersdorp).

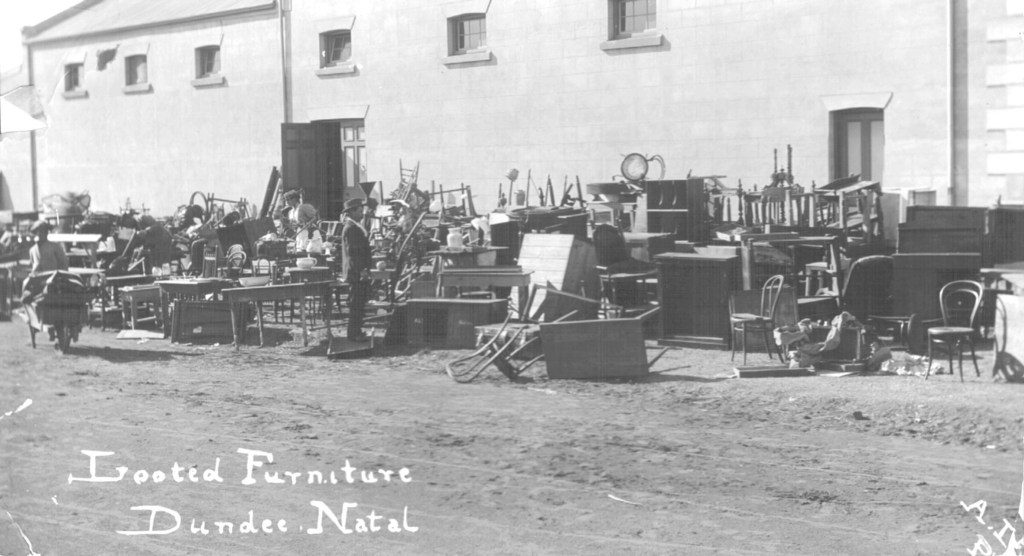

Both Newcastle and Dundee are looted extensively, Republican Burghers also pillage surrounding villages, towns and farms – loading wagons with stolen goods. British farmers and their families are disposed of their property and stock and many are pushed as refugees into the veldt to fend for themselves – no shelter or food given as aid.

The looting spree is so intense the Boers even sacrifice their military objectives of speed and manoeuvrability to cut the British forces off from linking up at Ladysmith and taking Port Natal – the slow-down to loot and pillage takes precedence and it allows the British to re-group and dig-in, this is a fundamental military blunder which ultimately costs the Boers the war. The extent of some of the damage and destruction can be found in this eye-witness account, when the British consolidate and counter-attack:

“General Hildyard at Estcourt lost no-time in following up the retreating Boers. On Sunday morning tents were struck and the order was given for a forward march to Frere. At 8 a.m. the long column streamed out, and after a tiring march arrived at Frere at two o’clock in the afternoon.

All along the line of march were evidences of wanton destruction by the Boer commando. At each railway station the safes had been blown to pieces with dynamite; the lamps and furniture had been smashed to atoms; the papers, tickets, and books had been torn to pieces and lay strewn over the floors. The farmhouses had also suffered in like manner, valued trinkets and ornaments lying smashed among the debris of furniture, etc. The doors and windows had been burst open and broken to pieces with crowbars. But it is impossible to adequately describe the heartrending scenes which were enacted. To understand fully the wanton devastation which had been made in many a happy country home, it would be necessary to witness the scene of desolation.

The disloyal Natal Dutch appear to have been among the principal perpetrators of these acts of despoliation, for in many of their houses were afterwards found articles of furniture which had been taken from the homes of neighbouring English farmers. In one house were found five pianos, which had belonged to English homes in the district. But the enemy had not restricted these wicked acts of destruction to ‘ the interiors of the farmhouses only, for- in some cases orchards of young fruit trees had been chopped down and utterly destroyed, and iron rain-water tanks had been pierced through the sides, rendering them useless. Many a heart was bowed down with grief on beholding the home, which had meant years of work, thus destroyed in a few moments by a ruthless foe.

Much of the live-stock, that had not been driven away, had also been destroyed. Dead poultry were lying about in heaps at one farmstead, among them being fifty young turkeys. Cattle and sheep lay rotting in the paddocks. On another farm three hundred head of cattle and sheep had been destroyed with arsenical poison.

Truly it was a terrible scene ; and yet this destruction had been wrought by the offspring of a civilised European nation. The Law of Environment had here proved itself true in the evolution of this people dwelling among the savage and barbarous tribes of South Africa.”

Stott p. 122. The Boer invasion of Natal.

Images: Looted furniture – Dundee Natal, Talana Museum.

So, in reality – the country “stealing the gold” from private businesses and minting it was the ZAR (not Britain) and the country bringing women and children into the conflict first was the ZAR followed by the OFS and not the British, the countries in initial neglect of duty of care when dealing with civilian refugees are the ZAR and the OFS, the initial illegal looting and stealing of private property is attributed to the Boers and the peoples responsible for the first civilian deaths were the Boer Republics.

The Siege crisis

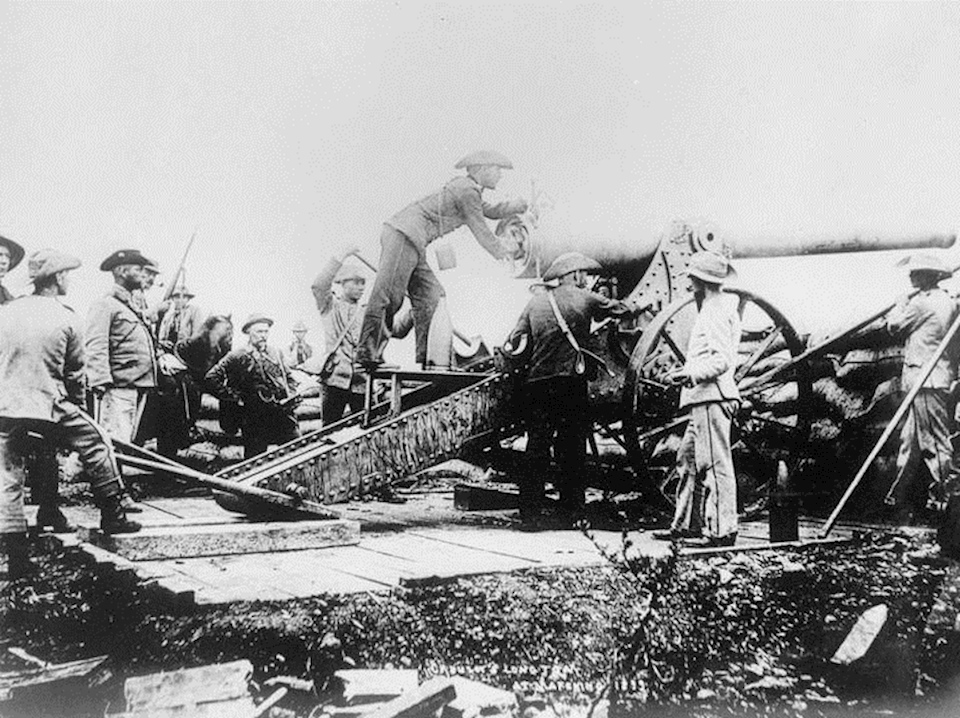

There are always “two sides to the story” and each side has merit in their argument, but let’s do try and stick to some of these basic facts. The Boers initiated the Johannesburg civilian ‘refugee’ crisis in Sep 1899 and northern natal civilian refugee crisis in Oct 1899 and then they started another civilian refugee crisis when they put British cities like Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley under siege during the first phase of the war from Oct 1899 to March 1900. The siege tactics – cutting water and food supplies, shelling townships, workers compounds and residence suburbs with artillery and the subsequent diseases, starvation and malnutrition killing thousands of civilians – black, white and coloured – over 3,000 in Kimberley alone (see The Battle of Magersfontein. By Dr. Garth Benneyworth).

Figures of civilian casualties during the sieges are well documented in the case of white civilians – recorded deaths include women and children killed by shellfire and well-known townspeople, what’s not recorded adequately is the death of civilians by disease, and the death of Black, Coloured and Indian citizens also caught up in the sieges. An example is Kimberley – a pavement plaque marks the first civilian casualty and it simply reads that here the first civilian was killed by Boer shellfire – an unknown black women. In Ladysmith the civilian burials at the provisional hospital amount some 600 casualties, mainly disease – and these are just the whites, no record is made of the Black and Indian Ladysmith civilians.

The Empire Strikes Back!

This is all a pre-curser to the refugee crisis the British created by engaging scorched earth policies issued mid 1900 to deal with insurgency and guerrilla warfare – and the subsequent burning down and destruction of the bittereinder’s farms’ as part of this policy and strategy.

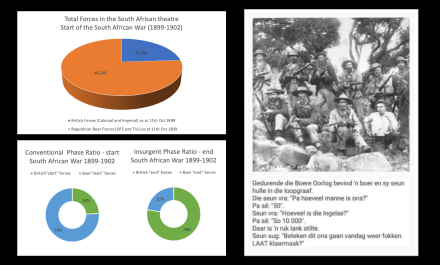

The British counter-attack to the Boer invasions in Oct 1899 is relentless and highly efficient. The British are able to consolidate from the setbacks of ‘Black-week’ in December 1899 whilst they are numerically disadvantaged and they manage to hold their major towns under siege. By the time their hastily assembled ‘Army Force’ begins to land from January 1900 and they are numerically matched – other than the set-back at Spionkop at the end of January 1900, they lose no other other major conventional battle and in a matter of just 6 months, relieve all the sieges of all their cities, dispatch the Republican forces from their colonies, take both the Boer capitals, take the economic hub that is Johannesburg, remove Boer Forces from all their invested defences, break the Boer’s fighting capability with the mass surrenders at Paadeberg and Brandwater Basin (9,000 Republican men in total) and cut the Boers from supply and foreign assistance from the sea. By July 1900, a mere 10 months in, the conflict is un-winnable for the Boers – the British attitude is the war is ‘done and dusted’ – the Boer capitals are in British hands and its back home before Christmas for tea and medals.

With extended and unprotected supply lines stretching all the way from Cape Town to Pretoria the British position in Pretoria is vulnerable. The Boers target these lines and start blowing up rail-line and shooting up trains as the main thrust of their newly devised guerrilla or insurgency campaign. Sick and tired of trains arriving in Pretoria full of holes or not at all, and highly annoyed with the chief protagonist of these tactical hit and runs – General Christiaan de Wet – Lord Roberts writes to Lord Kitchener on the 14th June 1900 and says:

“We must put a stop to these raids on our railway and telegraph lines, and the best way will be to let the inhabitants understand that they cannot be continued with impunity. Troops are now available and a commencement should be made tomorrow by burning De Wet’s farm… He like all Free Staters now fighting against us is a rebel and must be treated as such. Let it be known all over the country that in the event of any damage being done to the railway or telegraph the nearest farm will be burnt to the ground.”

The Boer decision to embark on guerrilla warfare and force all the Burghers who have taken up the offer and oaths of neutrality – to take up arms again and rejoin their Commando’s on threat of their farmsteads being destroyed – marks the point where the British military attitudes in South Africa turn from ‘Relentless’ to ‘Ruthless’.

On 16 June 1900, Roberts issues the proclamation on ‘scorched earth’ stating that, for every attack on a railway line the closest homestead would be burnt down. When that does not work, some months later another proclamation is issued in September stating that all homesteads would be burnt in a radius of 16 km of any attack, and that all livestock would be killed or taken away and all crops destroyed.

“Government Laagers”

This is followed by two separate Boer civilian refugee problems – one refugee crisis created by the Boer Republican Forces, burning down and destroying Hensopper, British and Joiner farms after the mid 1900 armistice proclamations – leaving these families in the veldt to fend for themselves – the Boers spurring the British to initiate the first concentration camps on the 22nd September 1900 specifically to deal with these ‘Hensopper’ refugees and give them a bell tent shelter, food and water … Maj. General J.G. Maxwell signals:

“… camps for burghers who voluntarily surrender are being formed at Pretoria and Bloemfontein.”

A proclamation was even issued by Lord Kitchener by 20th December 1900 which states that all burghers surrendering voluntarily, will be allowed to live with their families in these “Government Laagers” (concentration camps) until the end of the war and their stock and property will be respected and paid for.

And there is a second refugee crisis, this one initiated by the British forces and their scorched earth policy. The ‘concentration camps’ termed ‘refugee camps’ by the British (or ‘Government Laagers) start to fill up with a mix of Boers who have voluntarily surrendered (Hensoppers) or joined British forces (Joiners) and whose farms have been burned down by the Boers, they are also joined by some British families whose farms suffered the same fate (all these families comprise, men, women and children). They are then joined by ‘Bittereiner’ families directed to the concentration camps by the British who are busy burning down or dynamiting their farmsteads under the Scorched Earth policy – these families comprise a handful of men, but mainly women and children (their husbands still on Commando). Over time and given the sheer scale of destruction of the rural sector, the Bittereinder families start to outnumber the Hensopper families.

By 21st December 1900 Lord Kitchener outlined the advantages of interning all women, children and men unfit for military services, also Blacks living on Boer farms, as this will be;

“the most effective method of limiting the endurance of the guerrillas … The women and children brought in should be divided in two categories, viz.: 1st. Refugees, and the families of Neutrals, non-combatants, and surrendered Burghers. 2nd. Those whose husbands, fathers and sons are on Commando. The preference in accommodation, etc. should of course be given to the first class. With regard to Natives, it is not intended to clear (Native) locations, but only such and their stock as are on Boer farms.”

What gets created now are two separate camp systems, one for ‘whites’ and one for ‘natives’ (Blacks) and they are both fundamentally different in the way they are managed. The ‘white’ camps are structured using bell tents along military camp lines, shelter is provided by way a tent and food and water is provided – the camps are somewhat porous, there are no fences or armed guards and people can come and go with ‘refugee passes’ – isolation and lack of places go for alternate shelter keep the Boers in the camps. Medical facilities are also at hand, some camps better equipped than others.

However, and this is key, upfront these camps are very poorly managed, the military have other problems to deal with and are prioritised to do what they know best and fight – there are major problems with sanitation, some camps being better than others. The supply lines to these camps – medicine, food, tents etc. all situated along railway lines for this purpose, are also severely disrupted by the Boer insurgents blowing up railway line. Overcrowding, lack of tents, disrupted food, poor sanitation, poor water and limited medicines all become major issues.

Many people don’t fully understand the concentration camps systems or the phases of their administration, in a nutshell there are two distinctive phases:

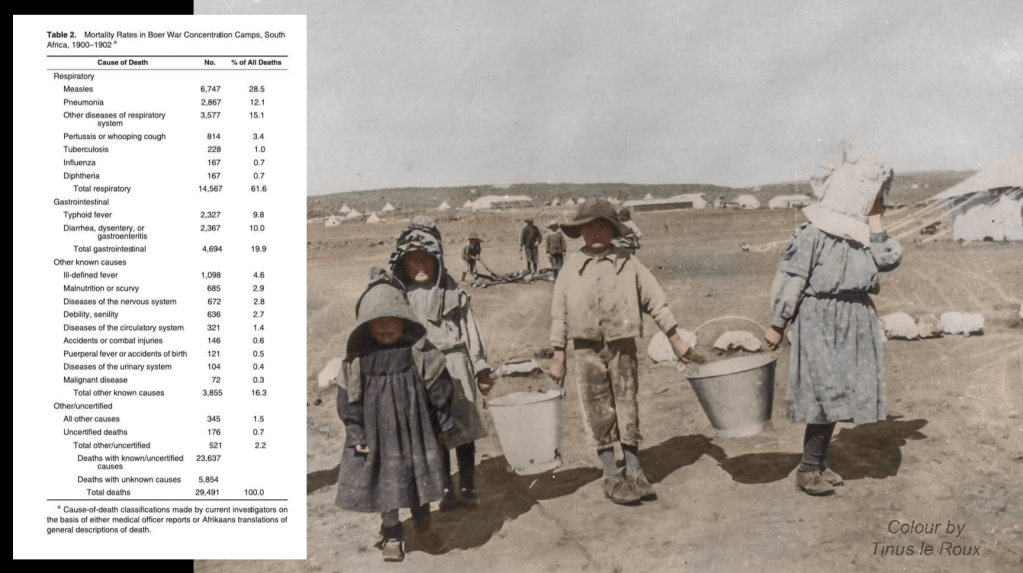

Phase 1: Started in September 1900 – they are set up under British military administration. In the ‘white’ camps – from March 1901 the mortality rates in the starts to climb to unprecedented and alarming levels, and at their peak the mortality rate is driven primarily by a measles epidemic which sweeps the camps and accounts 30% the overall deaths – as a child’s disease, along with the high infancy mortality rate and child death ratio in the Victorian period, coupled with the difficulty of wartime conditions and camp sanitary standards, by the beginning of 1902 children account for nearly 2/3 of all deaths.

The period March 1901 to November 1901 is 9 months of abject misery and suffering in the white Boer camps. However, contrary to modern propaganda, although there are many in white Boer camps who are malnourished and conditions are extremely harsh, they are not purposefully starved to death – ‘Starvation and Scurvy’ accounts for only 2.9% of recorded deaths. There are also no recoded cases of premeditated murder or executions, all deaths are attributed to disease or medically related conditions.

The conditions and plight of the women and children in the camps, against the context of respiratory and waterborne disease, coupled with inadequate medical countermeasures and failures in administration is highlighted by the likes of Emily Hobhouse and later in 1901 by the Fawcett Commission.

Phase 2: From November 1901 as a result of the Fawcett Commission’s and parliamentary recommendations, Lord Alfred Milner, the Cape Colony High Commissioner is tasked with taking over the white Boer camps from the military and bringing them under civilian authority instead.

As a result of Milner’s direct intervention, from November 1901 the mortality rates in the ‘white’ camps start to drop off dramatically as his civilian administrators and medical staff start to get on top of the epidemics, food supply and sanitary issues. They also do away with the putative and preferential treatment of ‘hensopper’ versus ‘bittereinder’ families initiated by the military.

Milner’s actions and policies are extremely effective, in just 4 months the mortality rates in the white camps drop to acceptable mortality rates for the Victorian era, made even more remarkable considering that these mortality rates are declining and have plateaued-out when the Guerrilla Phase and Scorched Earth policy is at its height and at its most destructive.

These “acceptable” i.e. normal mortality rates continue up to the end of the war on 31 May 1902 and then remain acceptable long after the end of the war as the camps are then used as ‘resettlement’ centres for displaced Boer families until the end of 1902.

As to Milner, it’s also an inconvenient truth, that a man so often vilified by modern white Afrikaners as the devil reincarnate, is the same man responsible for saving tens of thousands of Boer women and children’s lives. However in all, there are exactly 29,491 deaths recorded in the ‘white’ concentration camps, the result of which would deeply harm the white Afrikaner collective psyche and does so even to this day.

The ‘Black’ concentration camps are a different matter, on a point to note here, the ‘Black’ camps are very big, this population of displaced civilians throughout the war, be they from the farms or from the cities far outnumbers the whites. In the Black concentration camps, no food or shelter is afforded, Black internees are instructed to grow their own food, and provided seed for this purpose. The food is both for their own consumption and for the British war effort. Wages are paid for labour provided to the British war machine, and these wages are then used by the Africans in the camps to purchase shelters, provisions and food. Medical assistance is minimal. In terms of structure some of these camps start to reflect a modern day poor shack township – corrugated metal, mud, wood and canvass shacks. In a nut-shell these camps can best be described as ‘forced’ labour camps.

These ‘Black’ camps are hit by the same cocktail of viruses and bacteria that hit the ‘White’ camps, mainly typhoid and to a large degree measles. Their disease bell curve follows a similar trajectory as the white camps, however it starts a little later in August 1901. That’s were the similarity ends, in the Black camps there are also cases of starvation as the black populations do not receive enough food from the government to maintain human survivability (unlike the white camps). The mortality rates are also not clearly understood as they were not meticulously recorded (unlike the white camps). Only as late as 2024 do we even have an inkling of an idea of the mortality in these camps. They are now been carefully analysed using archaeological record (primary data, excavating and forensics) and oral history – it is now estimated that over 30,000 Black Africans died in these forced labour camps (refer Dr. Garth Benneyworth ‘Work or Starve’ published 2024).

Seeing the bigger picture

In reality, we now need to start accepting that as many Blacks died in their concentration camps (30,000 plus) as Whites died in their concentration camps (29,461). The key difference given racial prejudices (Boer and Brit) of the time, and more so the racial prejudices of the Afrikaner Nationalist governments after 1910.

So, before “Boer War” Afrikaner enthusiasts start jumping up and using this as yet another stick to vilify and beat the British with, we must note that whilst hundreds of plinths, monuments, museums and thousands of grave markers have focused on the “Boer Women and Children” at every single camp and in every single affected town – erected over the course of nearly 10 decades at massive state expense … and not one grave marker, monument, museum or even a simple single plinth was erected to the Black concentration camps.

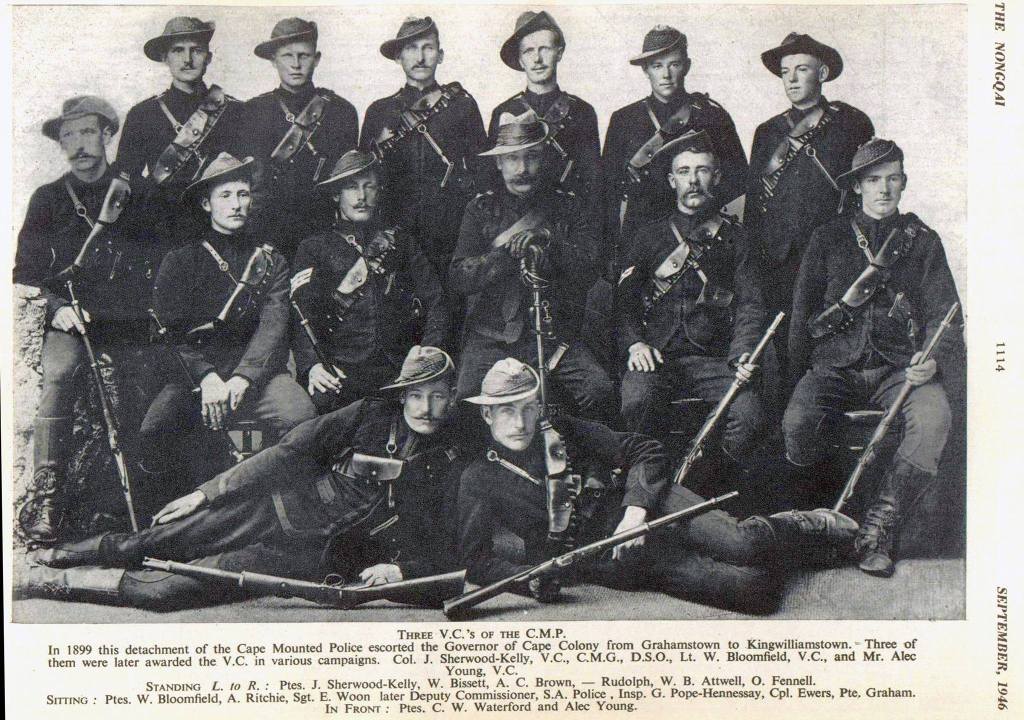

As to prejudice and misunderstanding of the Boer War – there remains to this very day no such acknowledgement and remembrance – still, and some still want to call it “The Anglo-Boer War” as if these are the only two groups in it and not by its official designated name “The South African War (1899-1902)” and they still exclude by way of simple acknowledgement the mass of other ethnicities who either took part in the war directly as belligerents – taking service directly in the British Army’s colonial regiments and units, over 30,000 as ‘Black African’ British combatants alone – and were not getting to the thousands of South African based ‘Coloureds’ and ‘Indians’ joining British forces.

Then there are the thousands of ‘armed’ black Agteryers’, labour and servants in the Boer Republican Armies – not to mention the Blacks affected by the war in their concentration camps as forced labour for the British by their tens of thousands.

Remember also that both the Tswana in Botswana and the Swazi enter the war as belligerent nations in their own right – on the side of the British, and both defeat Boer Commandos. There are literally hundreds of thousands of refugees having lost their jobs and been displaced from places like Johannesburg and Kimberley by the Boers or displaced from the Boer farms by the British – so here’s the kicker – there are more “Blacks’ affected by the war than either the Anglos or Boers combined and their death toll is as significant!

Heck, entire books and academic papers have been written by ‘British’ and then ‘Afrikaner’ historians – but this aspect of the war only started to appear with any degree of sincerity around 2015 – post 1994, and it’s still not fully researched.

War is Cruelty

The Boer’s Guerrilla campaign is not a romantic ‘scarlet pimpernel’ chase of Christian de Wet and his chums, all whilst they cleverly outsmart the British. It’s a brutal, harsh and very cruel campaign – aimed at public networks – trains and rail in addition to the military ones. It is marred by maundering – the destruction of public buildings, mission stations and farms in the British territories – and even the murder of British citizens. Here is just a flavour of it – mission stations and Black and Coloured British citizens and soldiers are especially targeted.

When the Reverend C. Schröder returned to his Gordonia congregation after the war, he was horrified to find that most of his flock had been killed by Boer raiders. A attack by an unhinged Manie Maritz on the Methodist mission station at Leliefontein in Namaqualand was especially savage. The mission station razed and plundered, the civilians hunted down in an act of revenge, in all 27 Leliefonteiners are killed (some accounts say a total of 43) and approximately 100 are injured. So brutal it even shocked Deneys Reitz who recorded it in his diary:

“We found the place sacked and gutted and among the rocks beyond the buried houses lay 20 or 30 dead Hottentots, still clutching their antiquated muzzleloaders. This was Maritz’s handiwork. He had ridden into the station with a few men to interview the European missionaries, when he was set upon by armed Hottentots, he and his escorts narrowly escaping with their lives. To avenge the insult, he returned the next morning with a stronger force and wiped out the settlement, which seemed to many of us a ruthless and unjustifiable act. General Smuts said nothing but I saw him walk past the boulders where the dead lay, and on his return he was moody and curt… we lived in an atmosphere of rotting corpses for some days.”

Deneys Reitz

Bill Nasson, the renowned Boer War historian would note:

“The wretched refugees of this massacre were pitilessly hunted down by parties of Boers. Those unfortunate enough to be captured were brought back to work as slave labourers. Indeed, they were even shackled in irons forged at the mission station’s smithy”.

Manie Maritz is so unhinged that later in the war, he ignores clear instructions from Smuts and attempts to dynamite the town of Okiep – its garrison and civilians included. Using the commandeered Namaqua United Copper Company locomotive ‘Pioneer’ to propel a mobile bomb in the form of a wagonload of dynamite into the besieged town. Luckily the attack failed when the train derailed.

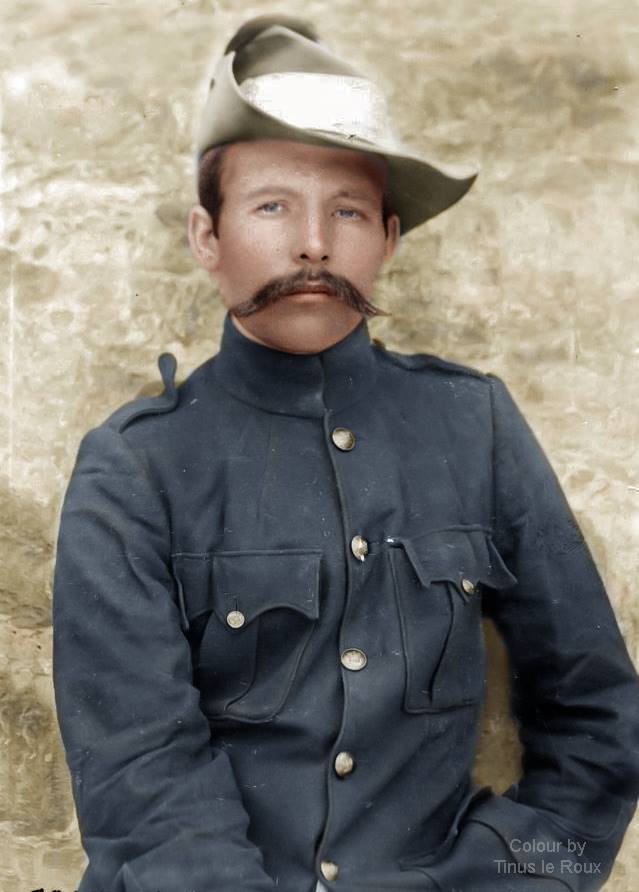

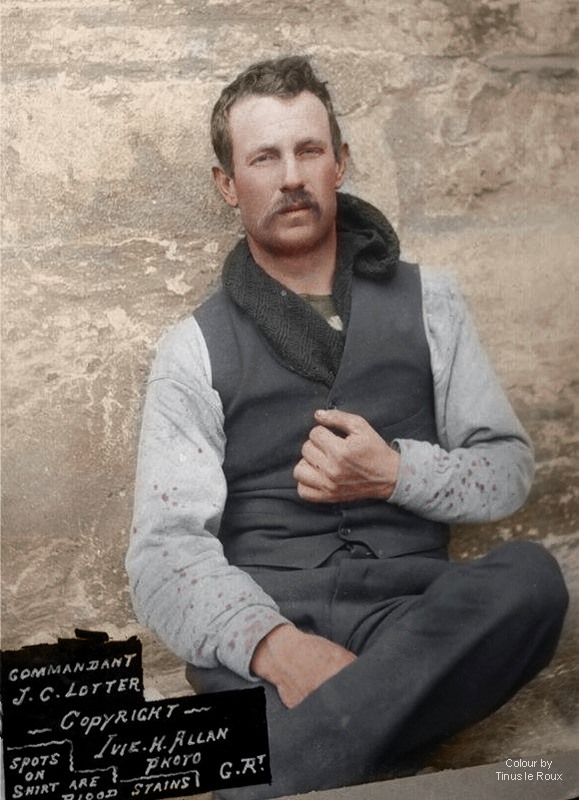

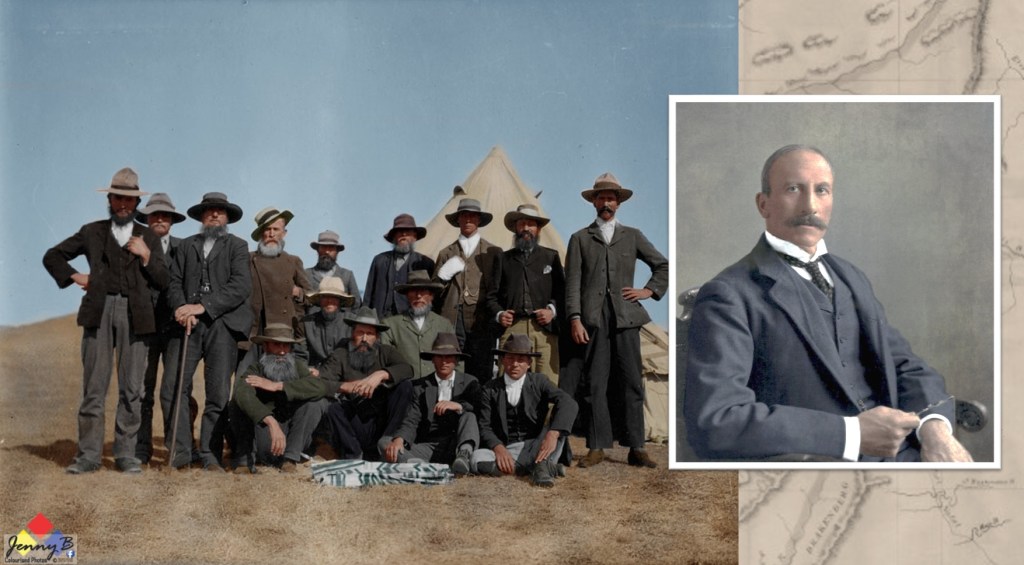

Maritz is not the only unhinged Boer Kommandant in the Guerrilla phase – both Kmdt. Gideon Scheepers and Kmdt. Hans Lötter, amongst other charges – were charged on marauding, property destruction, murdering “native spies” and mistreatment of black civilians (in the case of Scheepers also murdering unarmed but uniformed black British POW) – both were executed by the British once caught.

Images: Kommandant’s Scheepers and Lötter after their capture and ‘Fighting General’ Manie Maritz.

General Christian De Wet even writes to Lord Kitchener requesting clemency for Boer Kommandant’s executing Black soldiers out of hand as he had given “general instructions to have all armed natives and native spies shot.” Kitchener rejected the appeal, replying to General De Wet that Boer officers were personally responsible for their actions, and he wrote:

“[I am] astonished at the barbarous instructions you have given as regards the murder of natives who have behaved in my opinion, in an exemplary manner during the war.”

Ironically, as the modern Nationalist narrative went, Gideon Scheepers, Hans Lötter, Manie Maritz and Christiaan de Wet are all heralded as “volks-heroes” for their deeds, and this involves the outright murdering of black civilians, whereas Lord Kitchener, who would move on to become the face for British recruitment in World War 1, would ultimately be painted as the murderer incarnate.

The cruelty does not stop in the Cape, even General De la Rey’s victory over Lord Methuen’s column at Tweebosch on the 7th of March 1902 in the Transvaal at the end of the war is marred by war crimes. Tweebosch is famous because of General De la Rey’s compassionate and kind treatment of the wounded Lord Methuen and saving his life. What is not recorded at the Battle of Tweebosch in the narrative is the killing spree De la Rey’s commando members go on, as they execute about 30 unarmed Black wagon drivers and servants in service of the British column as well as black and Indian soldiers having surrendered. The testimony of the executions by survivors recently found in WO 108-117 in the UK’s National Archives give a unique and harrowing insight:

Here are some quotes on the killings of that day:

“…the whole Indian and Kaffir establishment of the F.V.H. (Field Veterinary Hospital … One Farrier Sergeant of the Indian Native Cavalry and two Indian Veterinary Assistants (men carrying no arms) were ruthlessly shot dead after the surrender, and nine Hospital Kaffirs were either killed in action or murdered later.”

(British Cavalry – Regimental History).

The Boers whom I met on the 8th instantly admitted that their men had deliberately shot down the transport Natives with a view, they asserted, of deterring others from enlisting in our services”.

Captain W.A. Tilney.

“I saw four Cape boys, unarmed and dismounted, come towards the Boers with their hands up. They were shot dead”.

Trooper C.J.J. Van Rensberg

“I saw a young Native boy riding a horse and leading another. He was unarmed. A Boer road up to him and told him to dismount. No sooner had he done so than the Boers shot him in the back of the head and killed him”.

Corporal H. Christopher

These testimony’s go on, there are loads – but its enough to get the point.

Even one of the most biased Republican Historians – Thomas Pakenham, has to acknowledge the slaughter of Blacks in the Transvaal by Republicans under the Command of Jan Smuts when he notes:

“When Jan Smuts’ commando fell on the native village at Modderfontein, for example, they butchered the 200 or so black inhabitants and left their bodies strewn around, unburied.”

The American General, William Tecumseh Sherman said something very relevant to war generally and the Boer War specifically – he said:

“War is cruelty. There is no use trying to reform it. The crueller it is, the sooner it will be over”.

General Sherman

One can easily see where the origins of the “you reap what you sow” ethos which enters into latter British mindsets when dealing with the Boer Republican refugees and their properties – a “hardening of attitudes” as it is often termed in modern military speak. Not even 40 years later, a ‘Rhodesian’ Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris would really crystallise this type of military sentiment to justify his carpet bombing of German civilians in World War 2 when he quoted Horsea 8:7 and said:

“They sowed the wind and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.”

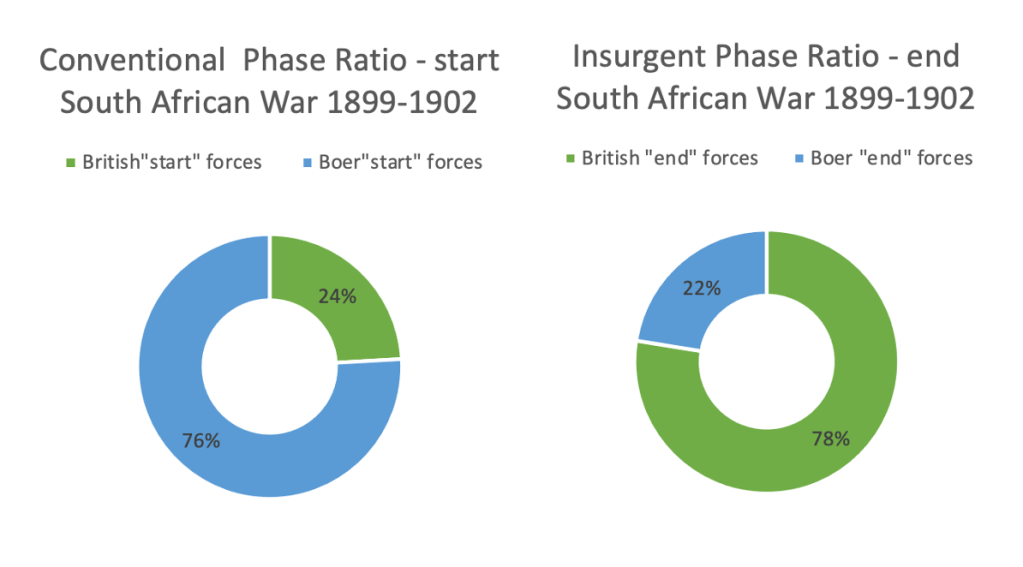

Also, to General Sherman’s point, the British fight the Boer’s guerrilla phase of the war with such intensity, the commitment of massive resources (8,000 blockhouses alone) and tens of thousands combatants – that the Guerrilla Phase of the Boer War is the shortest fought guerrilla war in the history of modern guerrilla warfare – it’s over in short time – less than 2 years (modern guerrilla warfare of this nature war lasts an average of 9 years), and here’s an uncomfortable fact, it’s over with the least trauma to the general population such warfare has traditionally invokes (then and now) – believe it or not.

The simple truth is the scale of destruction to property, lives and livelihoods is massive on both sides of the fence, so much so its almost impossible to separate the destruction initiated by the Boers and that initiated by the British given its scale – whole sections of the country in Boer territories destroyed and whole sections in British territories were also destroyed – thousands of Boer farms and entire British cities, farms, towns and mission stations … all destroyed.

To give an idea of the scale facing Milner at the end of the war, in trying to recover South Africa economically and deal with repatriations. There is the re-settlement of some 150,000 white civilians involved (mainly Boers) and about 50,000 impecunious white “foreigners” (mainly British) who had been employed on the Witwatersrand, and then there is approximately one million displaced and unemployed “Bantu” (read that again – 1,000,000 Black refugees).

Milner’s repatriation, economic reforms and compensations were naturally decried by latter day Afrikaner nationalists as insufficient – and that’s because they only focused on the Boers’ compensation and nobody else in the bigger picture. Milner, as a studious and rather bull-headed administrator, felt he did a decent enough job given the challenges he faced – and even some latter day economic historians would agree with him. But let’s face it – the community that come off worse, by a miracle mile, were the “Bantu”.

In Conclusion

This is not to say “tit for tat” – the Boers started it first bla … bla … bla! That would be disingenuous and disrespectful to their memory and that’s not the point of this missive – the point is to remind people who are hidebound by a rather poor Christian Nationalist education and blinkered by identity politics – that in war there are no saints, war is nasty, it’s cruel, there are never really any ‘winners’ in war, nothing happens in a vacuum – and in war the truth is always the first victim.

The idea that the white Boer civilians were the unwitting victims in this entire saga, that they are the only real community to really have suffered the ravages of this war at the hands of the British is completely unhinged, baseless and untrue. This sentiment rings more true to politicking and identity politics initiated by the Nationalists than it does to any historical fact.

In truth, both the Boers and the British are equally responsible for waging war, both can be held to account for the resultant civilian crisis that war inevitably produces and all the carnage that follows that, and very importantly they are both equally cruel … and citizens from all communities were traumatised, there is no clear ‘murderous villain’ … there never is in war.

Written and researched by Peter Dickens

References:

Complete history of the South African War: in 1899-1902 By F. T. Stevens. Published 1903.

The Boer Invasion of Natal : Clement Horner Stott. Published 1900.

Leopold Charles Maurice Stennett Amery “The Second Boer War – The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899-1902” – Volumes 1 to 7.

History of the war in South Africa 1899-1902. By Maj. General Sir Frederick Maurice and staff. Volumes 1 to 4, published 1906

The Boer War: By Thomas Pakenham – re-published version, 1st October 1991.

Black People and the South African War 1899-1902. By Peter Warwick. Published 1983.

The Battle of Magersfontein – Victory and Defeat on the South African Veld, 10-12 December 1899. Published 2023. By Dr. Garth Benneyworth.

Kruger’s War – the truth behind the myths of the Boer War: By Chris Ash, BSc FRGS FRHistS, published 2014.

A History of the British Cavalry, 1816-1919, Vol.4, p.270

Commando – By Deneys Reitz, published 1929

Work or Starve - Black concentration camps and forced labour camps in South Africa: 1901 – 1902, By Dr. Garth Benneyworth. Published 2024 by The War Museum of the Boer Republics.

Correspondence and fact checking with Dr. Garth Benneyworth, Boer War historian – Sol Plaatjies University, Kimberley – February 2024.

A tool for modernisation? The Boer concentration camps of the South African War, 1900-1902. By Dr Elizabeth van Heyningen – Department of Historical Studies, University of Cape Town, 2010 South African Journal of Science.

Correspondence and fact checking with Chris Ash, BSc FRGS FRHistS, Boer War historian, Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society for The Boer War Atlas – February 2024.

Correspondence to The Observation Post on Boer War Repatriation and Compensation – Jan 2024. By Gordon Mackinlay.

Correspondence and fact checking with Boer War historian – Robin Smith, Feb 2024.

With thanks to:

Colorised images on the mast-head thanks to Allan Wood (Kitchener) and Jenny B (de Wet)

Colourised images used with great thanks to both Jennifer Bosch and Tinus le Roux.

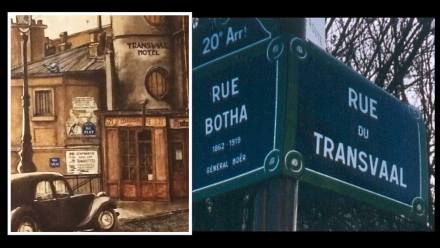

I glanced up at an art mural of the quarter depicting its early 20th Century heyday, and noticed its old landmark hotel was called the ‘Transvaal Hotel’, nipping outside I realised I was in the famous old ‘working class quarter’ of Paris, the epicentre of French equality and multiculturalism … Belleville … the birthplace and childhood home of Édith Piaf, with its panoramic view of the Paris at the Parc de Belleville, and I was standing in one its most well-known streets, leading to the Parc de Belleville, the ‘Rue du Transvaal’.

I glanced up at an art mural of the quarter depicting its early 20th Century heyday, and noticed its old landmark hotel was called the ‘Transvaal Hotel’, nipping outside I realised I was in the famous old ‘working class quarter’ of Paris, the epicentre of French equality and multiculturalism … Belleville … the birthplace and childhood home of Édith Piaf, with its panoramic view of the Paris at the Parc de Belleville, and I was standing in one its most well-known streets, leading to the Parc de Belleville, the ‘Rue du Transvaal’.

In their Republicanism and concepts of Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood they found kindred “Brothers’ in the form of the Boers of The Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State Republic, a hard ‘working class’ and determined people (like themselves) seeking ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’ from the oppressive yoke of British Class Elitism and Monarchism. The French fully supported the Boer cause for Republic autonomy and found Britain to be unduly pressuring them, and lets not forget – the Boers were up against their old enemy; “les rosbifs” (the roast beefs) – the English.

In their Republicanism and concepts of Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood they found kindred “Brothers’ in the form of the Boers of The Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State Republic, a hard ‘working class’ and determined people (like themselves) seeking ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’ from the oppressive yoke of British Class Elitism and Monarchism. The French fully supported the Boer cause for Republic autonomy and found Britain to be unduly pressuring them, and lets not forget – the Boers were up against their old enemy; “les rosbifs” (the roast beefs) – the English.

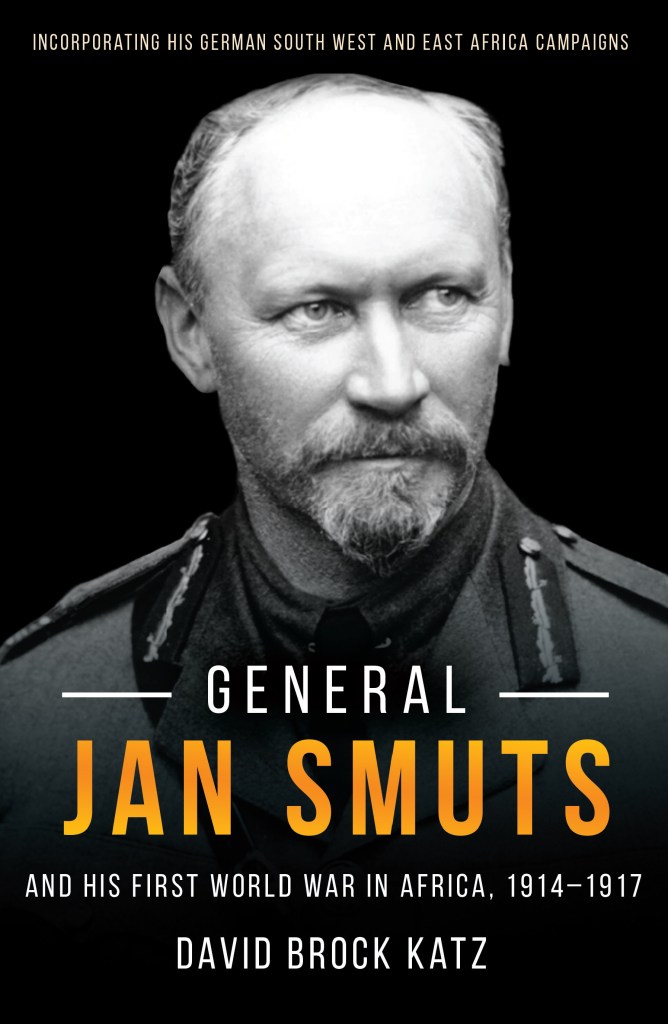

There are still a handful of conservative ‘Afrikaner nationalist’ white people in South Africa who would still toe the old Nationalist line on Smuts, that he was a ‘verraaier’ – a traitor to his people, his death welcomed. However, little do they know that many of the old Nationalist architects of Apartheid held Smuts in very high regard.

There are still a handful of conservative ‘Afrikaner nationalist’ white people in South Africa who would still toe the old Nationalist line on Smuts, that he was a ‘verraaier’ – a traitor to his people, his death welcomed. However, little do they know that many of the old Nationalist architects of Apartheid held Smuts in very high regard.

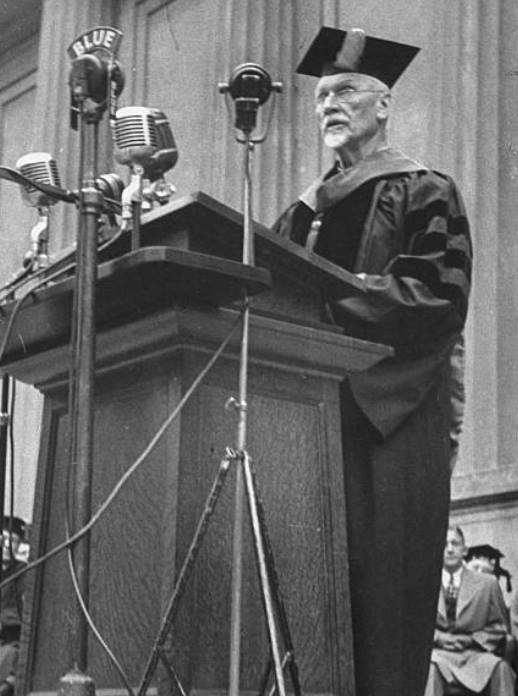

Smuts was honoured by many countries and on many occasions, as a standout Smuts was the first Prime Minister of a Commonwealth country (any country for that matter) to address both sitting Houses of the British Parliament – the Commons and the Lords during World War 2. To which he received a standing ovation from both houses.

Smuts was honoured by many countries and on many occasions, as a standout Smuts was the first Prime Minister of a Commonwealth country (any country for that matter) to address both sitting Houses of the British Parliament – the Commons and the Lords during World War 2. To which he received a standing ovation from both houses. Whilst studying law at Christ’s College at Cambridge University, he was rated as one of the top three students they have ever had (Christ’s College is nearly 600-year-old). The other two were John Milton and Charles Darwin.

Whilst studying law at Christ’s College at Cambridge University, he was rated as one of the top three students they have ever had (Christ’s College is nearly 600-year-old). The other two were John Milton and Charles Darwin.