The Diary of Walter Giddy

World War 1, Battle of Delville Wood, what better way to understand the carnage witnessed than by reading the writings of the young South Africans tasked to “hold the wood at all costs”.

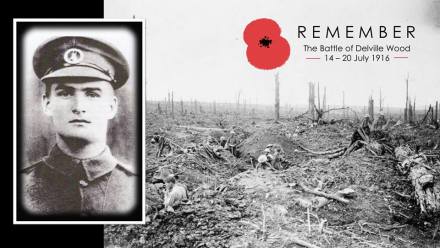

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was schooled at Dale College in King Williamstown. He voluntereed, together with friends, for overseas military service in 1915. He served in the 2nd S.A. Infantry Regiment. Having survived the battle of Delville Wood, he was killed by shrapnel on the 12th April 1917 near Fampoux. Walter Giddy is commemorated by a Special Memorial in Point du Jour Military Cemetery, Athies.

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was schooled at Dale College in King Williamstown. He voluntereed, together with friends, for overseas military service in 1915. He served in the 2nd S.A. Infantry Regiment. Having survived the battle of Delville Wood, he was killed by shrapnel on the 12th April 1917 near Fampoux. Walter Giddy is commemorated by a Special Memorial in Point du Jour Military Cemetery, Athies.

His diary was copied by his younger sister Kate Muriel Giddy/Morris.

Extracts from Walter’s Diary

4th July 1916

Still lying low in Suzanne Valley. The artillery are quietly moving up. We shifted up behind our old firing line, where the advance started 2 or 3 days ago. The dead are lying about. Germans and our men as well, haven’t had time to bury them. The trenches were nailed to the ground, and dead-mans-land looked like a ploughed field, heaps must be buried underneath…

5th July 1916

… it rained last night and we only have overcoats and waterproof sheets, but I cuddled up to old Fatty Roe, and slept quite warmly. There are no dug-outs where we are at present, and the shells are exploding uncomfortably near.

Had a man wounded last night for a kick off. The Huns are lying in heaps, one I noticed in particular had both legs blown off, and his head bashed in. Some have turned quite black from exposure. They are burying them as fast as possible. Brought an old fashioned power horn, Hun bullets, nose-caps of shells, etc., back with me, but I suppose they’ll be thrown away.

6th July 1916

Told to hold ourselves in readiness, expecting an attack. Received draft (£5) from Father.

7th July 1916

Made to sleep in the trench on account of the Hun shells flying a bit too near, had a cold rough night, but things have quietened a bit this morning, so we are back in our little shack made out of waterproofs. Bloody Fritz, he had started shelling the road, about 400 yards away and directly in line of us. A Frenchie was standing on the parapet and was excitedly beckoning to us. He’d put up his hands and point to a communication trench ahead. Couln’t make out what the beggar was driving at, so we ran up to him, and ahead were dozens of Hun prisoners filling out of the trench. It rained so hard our shack was just a mud-pool, busy drying our kit.

8th July 1916

3rd S.A.’s were relieved by the Yorks who went over this morning 400 strong and returned 150 strong. Then our S.A. Scottish went over with a couple of the Regiments and took the wood, and I believe lost heavily, but are still holding the wood.

Seaforth, Black Watch, Cameron, P.A., G.P.S. are going over in the morning, so there will be some bloodshed, if they get at close quarters with cold steel. Hun sent over some Tear Shells, which made our eyes smart, but were too far to cause much trouble. Two of our companies were up to the firing line, and T. Blake, of our platoon, acting as guide, had his jaw bone shattered, and another man had his head blown off. Three guns of the 9th R.F.A. were put out of action, they say the Huns have “smelt a rat”, and brought 12″ and 9.2 guns up, so I guess we shall have a lively time. I’d love to see the four “Jock” Regiments go over in the morning. The Huns hate them like poison, yet I do no think their hate exceeds their fear. For them, 100 and more prisoners have been brought in, past us. The Huns were sending shells over our heads, all day, one dropped in the valley, below, killing two and wounding five of the R.F.A.

9th July 1916

Shall never forget it, as long as I live. Coming up the trench we were shelled the whole time, and to see a string a wounded making their way to a dressing station, those who can walk or hobble along ; another chap had half of his head taken off, and was sitting in a huddled up position, on the side of the trench, blood streaming on to his boots, and Jock lay not 5 yards further with his stomach all burst open, in the middle of the trench. Those are only a few instances of the gruesome sights we see daily. A I am writing here, a big shell plonked into the soft earth, covering me with dust, one by one they are bursting around us. I am just wondering if the next will catch us (no it was just over). Oh ! I thought one wound get us, it plonked slick in our trench and killed old Fatty Roe, and wounded Keefe, Sammy who was next to me, and Sid Phillips, poor beggar, he is still lying next to me, the stretcher bearers are too busy to fetch him away.

The Manchesters had to evacuate the wood below us, and we the one along here. I’m wondering if we will be able to hold this wood, in case of an attack, as our number is so diminished. I’ve seen so cruel sights today. I was all covered in my little dug out, when old Sammy was wounded, had a miraculous escape.

10th July 1916

Still hanging on, and the shells flying round, three more of our fellows wounded, out of our platoon. Took Fatty Roe’s valuables off him and handed them over to Sergeant Restall… We have no dug-outs, just in an open trench. Of course we’ve dug in a bit, but its no protection against those big German shells… Harold Alger has been badly knocked about. I’m afraid he won’t pull through, arm and leg shattered by shrapnel. I had a lucky escape while talking to Lieutenant Davis, a piece of shrapnel hit on my steel helmet, and glanced past his head. He ramarked “That saved you from a nasty wound”, (referring to the helmet). The S.A. lads in our platoon have stuck it splendily, it has been a tough trial this.

We heard cries from the wood further down, and Geoghan and Edkins went to investigate, finding three wounded men lying down in the open. They had been lying there three days among their own dead, and had been buried a couple of times by their own shells, and the one brought in had been wounded again. They asked for four volunteers to bring in the other two, so off we went. It was an awful half hour, but we were well repaid by the grateful looks on their haggard faces. Poor old Geoghan was hit, his head was split off by shrapnel. Four of us buried him this morning.

11th July 1916

We were relieved by our own Scottish, and are back at our former camping ground, but I do feel so lonely, out of our mess of 5, only 2 of us left and my half section gone as well. We were right through the Egyptian Campaign tog, as half sections.

A Yorkshire man brought a prisoner over this morning, while we were still in the trenches, and he halted to have a chat. Our Corporal could speak German, so he gave the prisoner a cig. and he told us all we wanted to know. He was a Saxon and was heartily sick of the war, and our artillery was playing up havoc with their infantry, since the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. I didn’t say anything, but their artillery had given our men as much as they could bear.

12th July 1916

About 2 miles back and still the Huns had the neck tu put a shell into us, killing one man and wounding another. The Rev. Cook was killed while helping to carry in wounded. I have just been watching the Huns shelling the wood we came out of yesterday. It looks as though the wood is on fire, the smoke rising from the bursting shells. The Scottish (ours) relieved us too, and we lost 16 out of our platoon in it. It was a cruel three days, espacially when Manchester were driven out of the woods, 700 yards, in front of us, we were expecting the Huns over any minute, but the Huns would have got a warm reception. Then the Bedfords retook the wood, the full morning, which strengthened our position.

13th July 1916

Allyman found us again bending. I thought we were so safe for a bit. A shell planked out into the next dug-out to mine, killing Smithy and wounding Edkins, Lonsdale, Redwood and Bob Thompson, 3 of them belonging to our section. Only 3 of us left in Sammy’s old section. It’s a cruel war this. Just going up to dig graves to bury our dead. We buried Private Redwood, Smith and Colonel Jones, of The Scottish. General Lukin was at the funeral, he did look so worried and old.

14th July 1916

News very good this morning. our troops driving the Huns back, and the cavalry have just passed, they look so fine. The Bengal Lancers were among them, so I was told. We’re under orders to shift at a moment notice. It rained heavily this morning. I hope it does not hamper the movements of the cavalry. If this move ends as successfully as it has begun, it will mean such a lot to the bringing of the war to an end. Our chaps are getting so tired of the mud and damp. There’s such a change in the sunburnt faces of Egypt, and this inactivity makes one as weak as a rat. The cavalry have done excellent work, now it remains to us infantry to consolidate the positions. We’re just ready to move forward…

15th/16th July 1916

We (South African Brigade) went into Delville Wood and drove the Huns out of it, and entrenched ourselves on the edge, losing many men, but we drove them off, as they wound come back and counter attack. Then snipers were knocking our fellows over wholesale, while we were digging trenches, but our chaps kept them off. I got behind a tree, just with my right eye and shoulder showing, and blazed away.

We held the trench, and on the night of the 16th July they made a hot attack on out left, 16 of them breaking through, and a bombing party was called to go and bomb them out (I was one of the men picked). We got four and the rest of them cleared out. It rained all night, and we were ankle deep in mud, rifles covered with mud, try as we would, to keep them clean.

17th-20th July 1916

The Huns started shelling us, and it was just murder from then until 2 o’clock of the afternoon of the 18th, when we got the order to get out as best you can. I came out with Corporal Farrow, but how we managed it, goodness knows, men lying all over shattered to pieces, by shell fire, and the wood was raked by machine guns and rifle fire. Major McLeod of the Scottish was splendid. I have never seen a pluckier man, he tried his level best to get as many out as possible. We fall back to the valley below, and formed up again. I came on to camp and was ordered by the Doctor to remain here, having a slight attack of shell shock. I believe the 9th took the wood again, and were immediately relieved, but the lads are turning up again in camp, the few lucky ones. If it was not for a hole in my steel helmet, and a bruise on the tip, I would think it was an awful nightmare…The lads stuck it well, but the wood was absolutely flattened, no human being could live in it.

Major McLeod was wounded, and I gave him a hand to get out, but he would have I was to push on, as I would be killed. Many a silent prayer did I sent up, for strength to bring me through safely. I found a Sergeant of the 1st all of a shake, suffering from shell shock, so I took his arm and managed to get him to the dressing station. Just shaken hands with my old pal John Forbes. He is wounded in the arm and is off to Blighty. I quite envy him.

A sad day of S.A… They say we made a name for ourselves but at what a cost. All the 9th are resting on a hillside. Small parties of 25 to 40 men form the companies, which were 200 strong a short two weeks ago. We have taken back several miles…

21st July 1916

Had a bathe in the Somme, and a change of underwear, now lying on the green hillside listening to our Division band, a happy day for the lads that were lucky enough to come through.

22nd July 1916

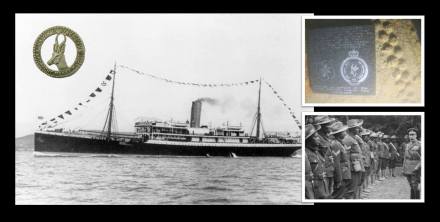

… General Lukin had us gathered round him, and thanked us for the splendid way in which we fought in Delville and Bernafay Woods. He said we got orders to take and hold the woods, at all costs, and we did for four days and four nights, and when told to fall back on the trench, we did it in a soldier like way. He knew his boys would, and he was prouder of us now, than even before, if he possibly could be, as he always was proud of South Africans. All he regretted was the great loss of gallant comrades, and thanked us from the bottom of his heart for what we had done.

Related Links and Work

Springbok Valour – Battle of Delville Wood Centenary ‘Springbok Valour’… Somme 100 & the Delville Wood Centenary

In Flanders Fields (Afrikaans) ‘In Flanders Fields’ translated into Afrikaans for the Somme 100 commemoration, July 2016

William Faulds VC Taking gallantry at Delville Wood to a whole new level; William Faulds VC MC

The Battle of Delville Wood 500 shells/min fell on the Springboks … “the bloodiest battle hell of 1916”

Mascots at Delville Wood: Nancy the Springbok Nancy the Springbok

Mascots at Delville Wood: Jackie the Baboon Jackie; The South African Baboon soldier of World War One

Posted by Peter Dickens

With the courtesy of the nephew of Walter Giddy, John Morris of Knysna, South Africa, and his daughters Kathy Morris/Ansermino of Vancouver, Canada, and Wendy Morris/Delbeke of Deerlijk, Belgium

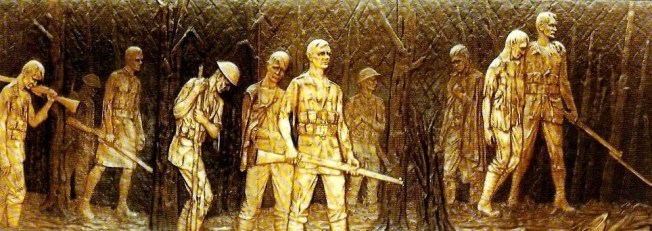

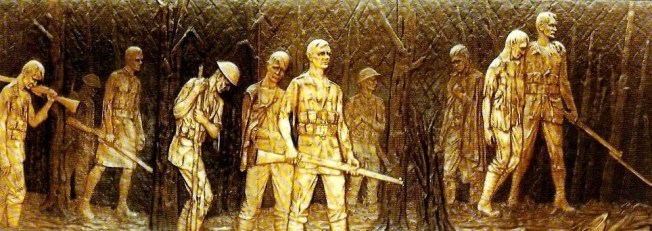

Feature image: Illustrated London News Lithograph by the Spanish artist – José Simont Guillén (1875-1968)

Insert illustration: Frank Dadd from a description of the Battle of Delville Wood by a British Officer. The Graphic Aug 19, 1916

Insert Image: Brass relief depicting a group of South Africans leaving Delville Wood after the battle, located at the Delville Wood Museum in France. Brass by sculpter Danie de Jager.

Walter Giddy image and post content courtesy The Delville Wood memorial – website www.delvillewood.com

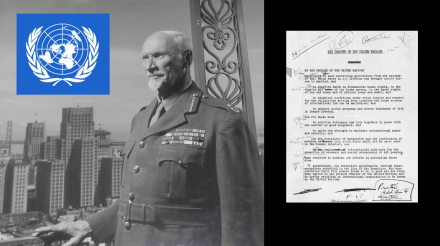

However it was ‘Smuts report’ of August 1917 in response to the second of these questions that led to the recommendation to establish a separate Air Service. In making his recommendations Smuts commented that

However it was ‘Smuts report’ of August 1917 in response to the second of these questions that led to the recommendation to establish a separate Air Service. In making his recommendations Smuts commented that

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was scho

Walter Giddy was born at Barkly East, Cape Province, South Africa, in 1895. He was the third son of Henry Richard Giddy and Catherine Octavia Dicks/Giddy. Walter was scho

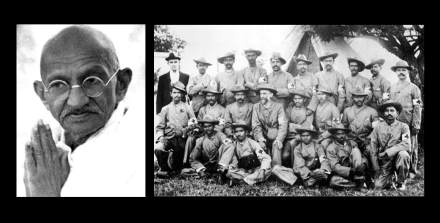

In this context rose a young, British educated lawyer – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who emigrated to the British Colonies in Southern Africa to make a name for himself and start a new life. He was at the start of his life quite supportive of British policies in South Africa and those of British empire and expansion.

In this context rose a young, British educated lawyer – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi who emigrated to the British Colonies in Southern Africa to make a name for himself and start a new life. He was at the start of his life quite supportive of British policies in South Africa and those of British empire and expansion.

“My first meeting with Mr. M. Gandhi was under strange circumstances. It was on the road from Spion Kop, after the fateful retirement of the British troops in January 1900.

“My first meeting with Mr. M. Gandhi was under strange circumstances. It was on the road from Spion Kop, after the fateful retirement of the British troops in January 1900.

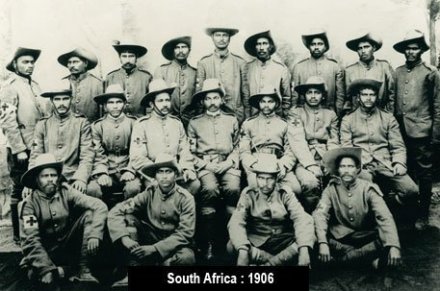

The Zulu uprising in Natal during 1906 was the result of a series of culminating factors and misfortunes; an economic slump following the end of the Boer War, simmering discontent at the influx of White and Indian immigration causing demographic changes in the landscape, a devastating outbreaks of rinderpest among cattle and a rise in a quasi-religious separatist movement with a rallying call of ‘Africa for the Africans’.

The Zulu uprising in Natal during 1906 was the result of a series of culminating factors and misfortunes; an economic slump following the end of the Boer War, simmering discontent at the influx of White and Indian immigration causing demographic changes in the landscape, a devastating outbreaks of rinderpest among cattle and a rise in a quasi-religious separatist movement with a rallying call of ‘Africa for the Africans’.

South African. The South Army (and Air Force) was issued with a “Polo” style “Pith” helmet. Made from cork it was not intended to protect the head from flying bullets and shrapnel, that was the purpose of the British Mk 2 Brodie helmet (also issued to South Africans). The pith helmet was worn mainly as sun protection when not in combat.

South African. The South Army (and Air Force) was issued with a “Polo” style “Pith” helmet. Made from cork it was not intended to protect the head from flying bullets and shrapnel, that was the purpose of the British Mk 2 Brodie helmet (also issued to South Africans). The pith helmet was worn mainly as sun protection when not in combat. Australia. The Australian army wore the “slouch hat”, also intended for sun protection when not in combat, like the South Africans they where issued with the British “Brodie” Mk2 steel helmet when in combat.

Australia. The Australian army wore the “slouch hat”, also intended for sun protection when not in combat, like the South Africans they where issued with the British “Brodie” Mk2 steel helmet when in combat. In addition to Australians, believe it or not some South African units also wore the “slouch hat”. Most notable was the South African Native Military Corps members, who made up about 48% of the South African standing army albeit in non frontline combat roles during both WW1 and WW2. The legacy of the “slouch” in the modern South African National Defence Force is however now on the decline and little remains now of its use, a pity as it would be a gracious nod to the very large “black” community contribution to both WW1 and WW2.

In addition to Australians, believe it or not some South African units also wore the “slouch hat”. Most notable was the South African Native Military Corps members, who made up about 48% of the South African standing army albeit in non frontline combat roles during both WW1 and WW2. The legacy of the “slouch” in the modern South African National Defence Force is however now on the decline and little remains now of its use, a pity as it would be a gracious nod to the very large “black” community contribution to both WW1 and WW2. In an iconic Australian War Memorial photograph to demonstrate this unique association, a Australian soldier working on the Beirut-Tripoli railway link is seen here chatting with two members of a South African Pioneer Unit (SA Native Military Corps) also working on the railway. The photo is designed to show off their similarities of dress and bearing and promote mutual purpose.

In an iconic Australian War Memorial photograph to demonstrate this unique association, a Australian soldier working on the Beirut-Tripoli railway link is seen here chatting with two members of a South African Pioneer Unit (SA Native Military Corps) also working on the railway. The photo is designed to show off their similarities of dress and bearing and promote mutual purpose. Interestingly the gun in the pit is not South African standard issue. Instead it is a British made Hotchkiss Portative MK 1, which was used by the Australians, dating back to World War 1, so it is probably their gun pit. Of French design the MK I was a .303 caliber machine gun, used in ‘cavalry/infantry’ configuration, with removable steel buttstock and a light tripod. This gun is normally fed from either flexible “belts” or strips like you see in the featured image. Normal Hotchkiss Portative strips hold 30 rounds each.

Interestingly the gun in the pit is not South African standard issue. Instead it is a British made Hotchkiss Portative MK 1, which was used by the Australians, dating back to World War 1, so it is probably their gun pit. Of French design the MK I was a .303 caliber machine gun, used in ‘cavalry/infantry’ configuration, with removable steel buttstock and a light tripod. This gun is normally fed from either flexible “belts” or strips like you see in the featured image. Normal Hotchkiss Portative strips hold 30 rounds each.